Barassi Line

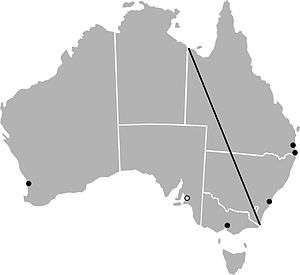

The "Barassi Line" is an imaginary line in Australia which divides areas where Australian rules football is more popular than rugby league and rugby union and vice versa. It was first used by historian Ian Turner in his "1978 Ron Barassi Memorial Lecture".[1] Crowd figures, media coverage, and participation rates are heavily skewed in favour of the code that is most dominant on either side of the line.[2][3]

Despite Australia's relatively homogeneous culture, the dichotomy existing in the country's sporting culture as represented by the line has endured since Australian rules football and rugby football developed distinct identities. Australian rules football is the most popular football code played to the west and south of the line, with centres in Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide, while rugby league and rugby union are more popular on the other side, with centres in Sydney and Brisbane. Each side represents roughly half of the Australian population, due to the concentration of population on the east coast.[4]

At the time the term was first used, there were no professional teams or leagues located on each code's opposite side of the line. However, in the years since, the Australian Football League (AFL) in Australian rules football and the National Rugby League (NRL) in rugby league have expanded their domestic competitions to include teams from both sides of the line. In addition, the multinational body SANZAAR, which organises the Super Rugby competition in rugby union, has expanded its Australian presence on the opposite side of the line.

The line runs from the Northern Territory-Queensland border, south through Birdsville, Queensland, through southern New South Wales north of the Riverina, through Canberra and on to the Pacific Ocean at Cape Howe on the border of New South Wales and Victoria.[5] The exact location of the division may be disputed and the stylised straight line is not particularly accurate in representing the division. No areas of Queensland favour Australian rules football over rugby league and, in the Riverina area in southern New South Wales, both codes vie for dominance. In the Canberra area, there is one professional team playing rugby union, the Brumbies, and one rugby league team, the Canberra Raiders, whereas there is no AFL side in Canberra, and only a few matches are played there each year, even though many Australian rules football teams compete in Canberra at levels lower than the AFL.

Other sports have no such separation in Australia. Cricket has been played on a national scale by state representative teams for over 100 years, and in 1977 soccer became the first sport in Australia to start a club based national league.[6]

Origin

The Ron Barassi Memorial Lecture was a series of lectures given between 1966 and 1978 by Ian Turner, a professor of history at Monash University, that were named after Ron Barassi, Sr..[7] Barassi played a number of Australian rules football games for Melbourne in the Victorian Football League (VFL) before enlisting to fight in World War II and subsequently dying from shrapnel wounds.[8]

The Barassi Line itself was named after Ron Barassi, the former Barassi's son, who was a star player for Melbourne and Carlton and a premiership-winning coach with Carlton and North Melbourne. He believed in spreading the code of Australian rules football around the nation with an evangelical zeal, and became coach and major supporter of the relocated Sydney Swans. He foresaw a time when Australian rules football clubs from around Australia, including up to four from New South Wales and Queensland, would play in a national football league with only a handful of them based in Melbourne, but his prognostications were largely ridiculed at the time.[9]

League structures and expansions

The pursuit of national exposure for sports is influenced by the ratings systems used by Australian television. By the late 1980s, the main football codes in Australia realised that in order to garner the desired high national ratings, and increase the value of their product for television broadcast deals and corporate sponsors, they needed to maximise their national exposure.[10][11] This meant heavy investment in grassroots development and in the support of clubs on the "other" side of the Barassi Line.

Australian rules football

The Victorian Football League's South Melbourne Football Club relocated to Sydney and became the Sydney Swans in 1982. The Sydney Swans endured limited success and a series of wooden spoons in their first decade in Sydney before rallying for a series of good years in the mid-1990s onward,[12] culminating in premierships in 2005 and 2012. The Brisbane Bears were founded as an expansion team to the VFL in 1986 and also had poor results, with back-to-back wooden spoons until they were the beneficiaries of a forced merger with the Melbourne-based Fitzroy Lions in 1996. The Brisbane Lions were formed and became the first triple-premiership winner in 46 years, winning in 2001, 2002 and 2003.[13]

In 1990, the Victorian Football League changed its name to the Australian Football League (AFL) to pursue a more national focus. By 1997, six of sixteen AFL clubs were based outside of Victoria, but only two on the Rugby League side of the Barassi Line.

A second Queensland team on the Gold Coast joined the competition in 2011, and a second New South Wales team, based in Western Sydney, joined the AFL in 2012. With the establishment of these clubs, Ron Barassi Jr's prophecy of a national Australian rules football league with four teams in New South Wales and Queensland has been fulfilled. A major reason for the expansion into these non-traditional areas has been to increase both the number of games played each week, and the potential television audience. This resulted in income from television rights rising dramatically.[14][15]

In 2011 the AFL also created the North East Australian Football League (NEAFL), a second level league comprising the reserve teams of the four AFL teams based in Queensland and New South Wales, along with high-level teams from the Northern Territory, Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. A junior academy system was also introduced with the aim to increase the participation rate of players from NSW and Queensland.[16]

As of 2019 the Greater Western Sydney Giants have an agreement to play four home games in Canberra during each season.

Rugby league

In 1995 the Australian Rugby League (ARL) created four new expansion teams including one in Perth, resulting in the first major rugby league club based on the Australian rules football side of the Barassi Line, the Western Reds. By the time the breakaway Super League started in 1997 a second club on the opposite side of the line was created, the Adelaide Rams. A third club on the opposite side of the line, the Melbourne Storm, was due to be created in 1998 to play in the second season of Super League but, in the meantime, the opposing leagues made restitution and established the National Rugby League (NRL).[17] Part of the agreement to form a new league included a reduction of clubs in the league, especially those recently established in difficult markets, resulting in the disbanding of the clubs in Perth and Adelaide.[18] The Melbourne Storm continued with success in the new competition, achieving their first premiership win in 1999.[19]

In the aftermath of the Super League war, the NRL is very guarded when it comes to expansion for rugby league.[20][21][22][23][24]

Despite this, there are official bids for expansion teams on both sides of the line; in Queensland, from Brisbane and Rockhampton, from the NSW Central Coast, Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea and Wellington in New Zealand on the home side, as well as from Perth on the other side.[25] The only NRL club on the non-traditional side of the Barassi Line remains the Melbourne Storm.

Rugby union

Rugby union has also attempted to expand on the Australian football side of the Barassi Line, with mixed results. Shortly after the sport went professional in August 1995, the Australian Rugby Union (ARU) joined forces with the New Zealand Rugby Football Union and South African Rugby Union to create the Super 12 competition. It began in 1996 with five regional franchises from New Zealand, four provincial teams from South Africa, and three state/territory teams from Australia. The three Australian teams were all on the traditional side of the Barassi Line; the Brisbane-based Reds, the Canberra-based Brumbies and the Sydney-based Waratahs. The league expanded by two teams, one each in Australia and South Africa, for 2006, with the competition then becoming the Super 14. Significantly, the new Australian team, the Western Force, was based in Perth on the opposite side of the line.

The following year, the ARU sought to create a national domestic competition, launching the Australian Rugby Championship (ARC). It launched with eight teams, with the Melbourne Rebels and Perth Spirit based on the opposite side of the line. However, the ARC lasted only one season.

The next expansion of rugby union on the opposite side of the line came in 2011, when the current Melbourne Rebels were added as Australia's fifth team in the newly renamed Super Rugby.

In 2013, the ARU announced that a new domestic competition, the National Rugby Championship (NRC), would start play in 2014. Of its nine inaugural teams, two were on the Australian rules side of the Barassi Line—Melbourne Rising and a revived Perth Spirit. Both teams remain in the league to this day.

Neither the Western Force or the Melbourne Rebels have qualified for the finals series in either the Super 14 or Super Rugby, while the Brumbies, Waratahs and Reds, from the traditional areas have all won championships. In 2017, the Western Force was cut from the Super Rugby competition for the 2018 season.[26] Teams from the Australian rules side of the line have enjoyed more success in the NRC. Both Melbourne Rising and Perth Spirit have made the finals series three times, and Perth won the NRC title in 2016.

Current situation

Four professional Australian football clubs, one rugby union Super Rugby club and one rugby league club, exist on the non-traditional side of the Barassi Line.

An academic study conducted from 2007 to 2011 shows that the traditional divide remains evident between the two sections of the Barassi Line. The study found:

Results indicated demarcation of viewer loyalty to each code based on geographic boundaries, [was] consistent with the existing notion of "the Barassi line". Both codes were shown to be largely reliant on traditional markets for driving television viewership figures, with little evidence to suggest either code expanded its national reach during the period, despite vastly contrasting broadcast strategies.

— Fujak, Hunter[27]

Australian rules football east of the line

Australian Capital Territory

Governing Body: AFL NSW/ACT

- AFL Women's (AFLW):

- No clubs

New South Wales

Governing Body: AFL NSW/ACT

- Australian Football League (AFL):

- 1982-present: Sydney Swans

- 2012-present: Greater Western Sydney Giants (Since 2012 play four home games per season in Canberra, ACT)

- AFL Women's (AFLW):

- 2017-present: Greater Western Sydney Giants (Women's)

Queensland

Governing Body: AFL Queensland

- Australian Football League (AFL):

- 1987-1996: Brisbane Bears

- 1997-present: Brisbane Lions

- 2011-present: Gold Coast Suns

- AFL Women's (AFLW):

- 2017-present: Brisbane Lions (Women's)

- 2020-present: Gold Coast Suns (Women's)

Rugby league west of the line

Northern Territory

Governing Body: Northern Territory Rugby League

- National Rugby League (NRL):

- No clubs

- NRL Women's Premiership (NRLW):

- No clubs

South Australia

Governing Body: South Australia Rugby League

- National Rugby League (NRL):

- 1997–1998: Adelaide Rams

- NRL Women's Premiership (NRLW):

- No clubs

Tasmania

Governing Body: Tasmanian Rugby League

- National Rugby League (NRL):

- No clubs

- NRL Women's Premiership (NRLW):

- No clubs

Victoria

Governing Body: Victorian Rugby League

- National Rugby League (NRL):

- 1998-present: Melbourne Storm

- NRL Women's Premiership (NRLW):

- No clubs

Western Australia

Governing Body: Western Australia Rugby League

- NRL Women's Premiership (NRLW):

- No clubs

Rugby union west of the line

Northern Territory

Governing Body: Northern Territory Rugby Union

- Australian Rugby Championship (ARC):

- No clubs

- Global Rapid Rugby (GRR):

- No clubs

- National Rugby Championship (NRC):

- 2018-present: Northern Territory Mosquitoes (Since 2018 play in NRC Division 2)

- Super Rugby:

- No clubs

- Super W:

- No clubs

South Australia

Governing Body: South Australia Rugby Union

- Australian Rugby Championship (ARC):

- No clubs

- Global Rapid Rugby (GRR):

- No clubs

- National Rugby Championship (NRC):

- 2018-present: Adelaide Black Falcons (Since 2018 play in NRC Division 2)

- 2019-present: South Australian U23 '(Since 2019 play in NRC Division 2)

- Super Rugby:

- No clubs

- Super W:

- No clubs

Tasmania

Governing Body: Tasmanian Rugby Union

- Australian Rugby Championship (ARC):

- No clubs

- Global Rapid Rugby (GRR):

- No clubs

- National Rugby Championship (NRC):

- 2018-present: Tasmania Jack Jumpers (Since 2018 play in NRC Division 2)

- Super Rugby:

- No clubs

- Super W:

- No clubs

Victoria

Governing Body: Victorian Rugby Union

- Global Rapid Rugby (GRR):

- No clubs

- National Rugby Championship (NRC):

- 2014-present: Melbourne Rising

- 2018-present: Victoria Country Barbarians (Since 2018 play in NRC Division 2)

- Super Rugby:

- 2011–present: Melbourne Rebels

- Super W:

- 2018-present: Melbourne Rebels (Women's)

Western Australia

Governing Body: RugbyWA

- Global Rapid Rugby (GRR):

- 2018-present: Western Force

- National Rugby Championship (NRC):

- 2014-2017: Perth Spirit

- 2018-present: Western Force

- 2019-present: Perth Gold (Since 2019 play in NRC Division 2)

- Super Rugby:

- 2006-2017: Western Force

- Super W:

- 2018: Western Force (Women's)

- 2019-present: RugbyWA (Women's)

References

- Referenced in Hutchinson, Garrie (1983). The Great Australian Book of Football Stories. Melbourne: Currey O'Neil.

- 4174.0 - Sports Attendance, Australia, 2005-06 Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine; Australian Bureau of Statistics; 25 January 2007: "Notably, the states and territories which had low attendance rates for rugby league had the highest attendance rates for Australian rules football."

- "The 'Barassi Line': Quantifying Australia's Great Sporting Divide" (PDF). 21 December 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stephen_Frawley2/publication/273772263_The_%27Barassi_Line%27_Quantifying_Australia%27s_Great_Sporting_Divide/links/58b5233d45851503bea059db/The-Barassi-Line-Quantifying-Australias-Great-Sporting-Divide.pdf Archived 12 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine p.102

- Marshall, Konrad (26 February 2016). "Where do rugby codes' strongholds turn to rules? At the 'Barassi Line', of course..." The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Johnny Warren (2002). Sheilas, Wogs and Poofters. Random House Australia. p. 179. ISBN 1-74051-121-2.

- D. B. Waterson, Turner, Ian Alexander Hamilton (1922 - 1978) Archived 25 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16, Melbourne University Press, 2002, pp 424-425.

- Main, Jim (2002). Fallen, the Ultimate Heroes: Footballers who Never Returned from War. Melbourne, Victoria: Crown Content. ISBN 1740950100.

- Hess, Rob and Nicholson, Matthew. Beyond the Barassi Line: The Origins and Diffusion of Football Codes in Australia

- Ten, Network. "TEN Sport". TenPlay - TEN Sport.

- "Subscribe to The Australian | Newspaper home delivery, website, iPad, iPhone & Android apps". theaustralian.com.au. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Halloran, Jessica (23 September 2005). "Bloods, sweat and tears: how the Swans became pride of Sydney - AFL - Sport". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Rucci, Michelangelo. "The fall of AFL football in Queensland, once the pride of the national game". The Advertiser (8 May 2015). Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hawthorne, Mark (25 March 2017). "Pay to play: how sports bodies keeping winning the TV great rights battles". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Cordy, Neil (7 May 2016). "The only level playing field is a cemetery". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Peace deal brings end to three disastrous years". The Nation. Google News. 27 December 1997.

- "Rivals bury the hatchet in Australia". The Nation. Google News. 25 December 1997.

- Boyd, Christopher (30 September 2009). "NRL grand final countdown No.3: 1999, Melbourne Storm v St George Illawarra".

- Brad Walter (20 November 2009). "TV money puts brakes on NRL expansion". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014.

- David Riccio (22 March 2014). "Lack of talent delaying expansion dreams". The Daily Telegraph. Australia.

- Phil Rothfield (1 April 2014). "Expanded 18-team competition and two new conferences would bring back tribalism to NRL". Fox NRL. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Todd Balym (25 October 2012). "NRL expansion being dropped from agenda until at least 2015". Herald Sun. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Kerr, Jack (2 March 2016). "The key battlefronts in the football expansion wars". ABC News. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Flo casts doubt on Perth NRL bid". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 February 2012.

- "Western Force culled from Super Rugby competition". The Daily Telegraph. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Fujak, Hunter (November 2012). An Analysis of Broadcasting and Attendance in the Australian Football Industry (PDF) (Master of Arts (Sport Studies)). University of Technology, Sydney. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013.

External links

- The Barassi Line Investigation by Colin Ross