Azolla

Azolla (mosquito fern, duckweed fern, fairy moss, water fern) is a genus of seven species of aquatic ferns in the family Salviniaceae. They are extremely reduced in form and specialized, looking nothing like other typical ferns but more resembling duckweed or some mosses. Azolla filiculoides is one of just two fern species for which a reference genome has been published.[2]

| Azolla Temporal range: Maastrichtian-Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Azolla caroliniana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida |

| Order: | Salviniales |

| Family: | Salviniaceae |

| Genus: | Azolla Lam.[1] |

| Type species | |

| A. filiculoides[1] | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Species

Section Rhizosperma

Section Azolla

Azolla cristata Kaulf. (this name takes priority over Azolla caroliniana Willd.)

Azolla filiculoides Lam.

Azolla rubra R.Br.

At least six extinct species are known from the fossil record:

- Azolla intertrappea Sahni & H.S. Rao, 1934 (Eocene, India)[7]

- Azolla berryi Brown, 1934 (Eocene, Green River Formation, Wyoming)[7]

- Azolla prisca Chandler & Reid, 1926 (Oligocene, London Clay, Isle of Wight)[7]

- Azolla tertiaria Berry, 1927 (Pliocene, Esmeralda Formation, Nevada)[7]

- Azolla primaeva (Penhallow) Arnold, 1955 (Eocene, Allenby Formation, British Columbia)[7]

- Azolla boliviensis Vajda & McLoughlin, 2005 (Maastrichtian - Paleocene, Eslaboacuten Formation and Flora Formation Bolivia)[8]

Ecology

Azolla is a highly productive plant. It doubles its biomass in 1.9 days or more,[9] depending on conditions, and yield can reach 8–10 tonnes fresh matter/ha in Asian rice fields. 37.8 t fresh weight/ha (2.78 t DM/ha dry weight) has been reported for Azolla pinnata in India (Hasan et al., 2009).[10]

Azolla filiculoides (red azolla) is the only member of this genus and of the family Azollaceae in Tasmania. It is a very common native aquatic plant in Tasmania. It is particularly common on farm dams and other still water bodies. The plants are small (usually only a few cm across) and float, but can be very abundant and form large mats. The plants are typically red, and have very small water repellent leaves. Azolla floats on the surface of water by means of numerous small, closely overlapping scale-like leaves, with their roots hanging in the water. They form a symbiotic relationship with the cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae, which fixes atmospheric nitrogen, giving the plant access to the essential nutrient. This has led to the plant being dubbed a "super-plant", as it can readily colonise areas of freshwater, and grow at great speed - doubling its biomass every two to three days. The typical limiting factor on its growth is phosphorus, another essential mineral. An abundance of phosphorus, due for example to eutrophication or chemical runoff, often leads to Azolla blooms. Unlike all other known plants, the symbiotic microorganism is transferred directly from one generation to the next. This has made Anabaena azollae completely dependent on its host, as several of its genes are either lost or has been transferred to the nucleus in Azolla's cells.[11]

The nitrogen-fixing capability of Azolla has led to Azolla being widely used as a biofertiliser, especially in parts of southeast Asia. Indeed, the plant has been used to bolster agricultural productivity in China for over a thousand years. When rice paddies are flooded in the spring, they can be inoculated with Azolla, which then quickly multiplies to cover the water, suppressing weeds. The rotting plant material releases nitrogen to the rice plants, providing up to nine tonnes of protein per hectare per year.[12]

Azolla are weeds in many parts of the world, entirely covering some bodies of water. The myth that no mosquito can penetrate the coating of fern to lay its eggs in the water gives the plant its common name "mosquito fern".[13]

Most of the species can produce large amounts of deoxyanthocyanins in response to various stresses,[14] including bright sunlight and extremes of temperature,[15][16] causing the water surface to appear to be covered with an intensely red carpet. Herbivore feeding induces accumulation of deoxyanthocyanins and leads to a reduction in the proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the fronds, thus lowering their palatability and nutritive value.[17]

Azolla cannot survive winters with prolonged freezing, so is often grown as an ornamental plant at high latitudes where it cannot establish itself firmly enough to become a weed. It is not tolerant of salinity; normal plants can't survive in greater than 1–1.6‰, and even conditioned organisms die in over 5.5‰ salinity.[18]

Reproduction

Azolla reproduces sexually, and asexually by splitting.

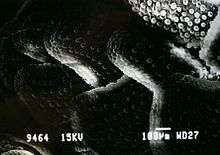

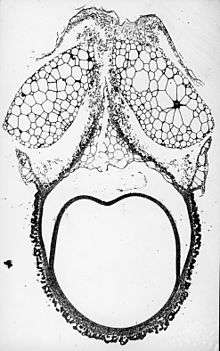

Like all ferns, sexual reproduction leads to spore formation, but Azolla sets itself apart from other members of its group by producing two kinds. During the summer months, numerous spherical structures called sporocarps form on the undersides of the branches. The male sporocarp is greenish or reddish and looks like the egg mass of an insect or spider. It is two millimeters in diameter, and inside are numerous male sporangia. Male spores (microspores) are extremely small and are produced inside each microsporangium. Curiously, microspores tend to adhere in clumps called massulae.[7]

Female sporocarps are much smaller, containing one sporangium and one functional spore. Since an individual female spore is considerably larger than a male spore, it is termed a megaspore.

Azolla has microscopic male and female gametophytes that develop inside the male and female spores. The female gametophyte protrudes from the megaspore and bears a small number of archegonia, each containing a single egg. The microspore forms a male gametophyte with a single antheridium which produces eight swimming sperm.[20] The barbed glochidia on the male spore clusters cause them to cling to the female megaspores, thus facilitating fertilization.

Human use

Food

In addition to its traditional cultivation as a bio-fertilizer for wetland paddy (due to its ability to fix nitrogen), azolla is finding increasing use for sustainable production of livestock feed.[21] Azolla is rich in proteins, essential amino acids, vitamins and minerals. Studies describe feeding azolla to dairy cattle, pigs, ducks, and chickens, with reported increases in milk production, weight of broiler chickens and egg production of layers, as compared to conventional feed. One FAO study describes how azolla integrates into a tropical biomass agricultural system, reducing the need for inputs.[22] Azolla has also been suggested as a food stuff for human consumption. However, no long term studies of the healthiness of eating Azolla have been made on humans [23] and Azolla may contain BMAA, a substance that is a possible cause of neurodegenerative diseases.[24] However, Azolla's cyanobacteria belongs to the genus Anabaena and species A. azollae,[25] previous studies had attributed neuro-toxin production to Anabaena flos-aquae species which is also a type of nitrogen fixing cyanobacteria.[26] Further research may be needed to ascertain if Anabaena azollae produces neuro-toxins.

Companion plant

Azolla has been used for at least one thousand years in rice paddies as a companion plant, because of the presence of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria in symbiosis with azolla, and its tendency to block out light to prevent any competition from other plants, aside from the rice, which is planted when tall enough to poke out of the water through the azolla layer. Mats of mature azolla can also be used as a weed-suppressing mulch.

Rice farmers used azolla as a rice biofertilizer 1500 years ago. The earliest known written record of this practice is in a book written by Jia Ssu Hsieh (Jia Si Xue) in 540 A.D on The Art of Feeding the People (Chih Min Tao Shu). By the end of the Ming dynasty in the early 17th century, azolla’s use as a green compost was being recorded in numerous local records.[27]

Larvicide

As an additional benefit to its role as a paddy biofertilizer, Azolla spp. have been used to control mosquito larvae in rice fields. The plant grows in a thick mat on the surface of the water, making it more difficult for the larvae to reach the surface to breathe, effectively choking the larvae.[28]

Invasive species

The fern has been introduced to other parts of the world, like United Kingdom, where it has become a pest in some areas. Even if it is a tropical plant, it has adapted to the colder climate. It can form up to 30cm thick mats that cover 100% of a water surface, preventing local insects and amphibians from reaching the surface.[29]

Importance in paleoclimatology

A study of Arctic paleoclimatology reported that Azolla may have had a significant role in reversing an increase in greenhouse effect that occurred 55 million years ago that caused the region around the north pole to turn into a hot, tropical environment. This research conducted by the Institute of Environmental Biology at Utrecht University indicates that massive patches of Azolla growing on the (then) freshwater surface of the Arctic Ocean consumed enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere for the global greenhouse effect to decline, eventually causing the formation of Ice sheets in Antarctica and the current "icehouse period" which we are still in. This theory has been termed the Azolla event.

Bioremediation

Azolla can remove chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, and lead from effluent. It can remove lead from solutions containing 1–1000 ppm.[30]

References

- In: Encyclopédie Méthodique, Botanique 1(1): 343. 1783. "Name - Azolla Lam". Tropicos. Saint Louis, Missouri: Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

Annotation: a sp. nov. reference for Azolla filiculoides

Type Specimens HT: Azolla filiculoides - Li, Fay-Wei; Brouwer, Paul; Carretero-Paulet, Lorenzo; Cheng, Shifeng; de Vries, Jan; Delaux, Pierre-Marc; Eily, Ariana; Koppers, Nils; Kuo, Li-Yaung (2018-07-02). "Fern genomes elucidate land plant evolution and cyanobacterial symbioses". Nature Plants. 4 (7): 460–472. doi:10.1038/s41477-018-0188-8. ISSN 2055-0278. PMC 6786969. PMID 29967517.

- Evrard, C.; Van Hove, C. (2004). "Taxonomy of the American Azolla" species (Azollaceae): A critical review". Systematics and Geography of Plants. 74: 301–318.

- "Name - Azolla Lam. subordinate taxa". Tropicos. Saint Louis, Missouri: Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- "Query Results for Genus Azolla". IPNI. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- Hussner, A. (2006). "NOBANIS -- Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet -- Azolla filiculoides" (PDF). Online Database of the North European and Baltic Network on Invasive Alien Species. Heinrich Heine Universität, Düsseldorf. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- Arnold, C.A. (1955). "A Tertiary Azolla from British Columbia" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum Of. Paleontology, University of Michigan. 12 (4): 37–45.

- Vajda, V; McLoughlin, S. (2005). "A new Maastrichtian-Paleocene Azolla species from Bolivia, with a comparison of the global record of coeval Azolla microfossils". Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology. 29 (2): 305–329. doi:10.1080/03115510508619308.

- Iwao Watanabe, Nilda S.Berja (1983). "The growth of four species of Azolla as affected by temperature". Aquatic Botany. 15 (2): 175–185. doi:10.1016/0304-3770(83)90027-X.

- "Hasan, M. R. ; Chakrabarti, R., 2009. Use of algae and aquatic macrophytes as feed in small-scale aquaculture: A review. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture technical paper, 531. FAO, Rome, Italy". fao.org/. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- The Arctic Azolla event - The Geological Society

- "FAO figures".

- "Mosquito Fern". America's Wetland Resource Center. Loyola University, New Orleans. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- Wagner, G.M. (1997). "Azolla: a review of its biology and utilization". Bot. Rev. 63: 1–26. doi:10.1007/BF02857915.

- Moore, A. W. (1969). "Azolla: Biology and agronomic significance". Bot. Rev. 35: 17–35. doi:10.1007/BF02859886.

- Zimmerman, William J. (1985). "Biomass and Pigment Production in Three Isolates of Azolla II. Response to Light and Temperature Stress". Ann. Bot. 56 (5): 701–709. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a087059.

- Cohen, M.F.; Meziane, T.; Tsuchiya, M.; Yamasaki, H. (2002). "Feeding deterrence of Azolla in relation to deoxyanthocyanin and fatty acid composition" (PDF). Aquatic Botany. 74 (2): 181–187. doi:10.1016/S0304-3770(02)00077-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- Brinkhuis, H.; Schouten, S.; Collinson, M.E.; Sluijs, A.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; Dickens, G.R.; Huber, M.; Cronin, T.M.; Onodera, J.; Takahashi, K.; et al. (2006). "Episodic fresh surface waters in the Eocene Arctic Ocean". Nature. 441 (7093): 606–9. doi:10.1038/nature04692. hdl:11250/174278. PMID 16752440. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Kempf, E.K. (1976). "Low Magnifications - A Marginal Area of Electron Microscopy". ZEISS Information. 21 (83): 57–60.

- AN EVOLUTIONARY SURVEY OF THE PLANT KINGDOM, by Robert F. Scagel, Robert J. Bandoni, Glenn E. Rouse, W. B. Schofield, Janet R. Stein, and T. M. Taylor, 1965: Belmont, California, Wadsworth Publishing Co., Inc., 658 pp.

- P. Kamalasanana Pillai, S. Premalatha and S. Rajamony. "Azolla – A sustainable feed substitute for livestock". Farming Matters magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- T.R. Preston and E. Murgueitio. "Sustainable intensive livestock systems for the humid tropics". FAO. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Sjodin, Erik (2012). The Azolla Cooking and cultivation Project. ISBN 978-9198068603.

- Erik Sjodin. "Azolla, BMAA, and Neurodegenerative Diseases". Retrieved 2015-01-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Anabaena

- Agnihotri, Vijai K. (2014). "Anabaena flos-aquae". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 44 (18): 1995–2037. doi:10.1080/10643389.2013.803797.

- "The East discovers Azolla". Azolla Foundation. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Myer, Landon; Okech, Bernard A.; Mwobobia, Isaac K.; Kamau, Anthony; Muiruri, Samuel; Mutiso, Noah; Nyambura, Joyce; Mwatele, Cassian; Amano, Teruaki (2008). Myer, Landon (ed.). "Use of Integrated Malaria Management Reduces Malaria in Kenya". PLOS ONE. 3 (12): e4050. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004050. PMC 2603594. PMID 19115000.

- Invasive non-native species (UK) – Water fern – Inside Ecology

- Robert L. Irvine; Subhas K. Sikdar (1998-01-08). Bioremediation Technologies: Principles and Practice. p. 102. ISBN 9781566765619.