Augustin Robespierre

Augustin Bon Joseph de Robespierre (21 January 1763 – 28 July 1794)[1] was the younger brother of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre.

Early life

Augustin was born in Arras, the youngest of four children of the lawyer Maximilien-Barthelemy-François de Robespierre and Jacqueline-Marguerite Carrault, the daughter of a brewer. His mother died when he was one year old, and his grief-stricken father abandoned the family to go to Bavaria, where he died in 1777.[2] He was brought up by two aunts. His brother Maximilien had won a scholarship from the Abbey of St. Vaast to pay for his studies at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand and had been such an outstanding student that when he obtained his degree in law, he asked the Abbot, Cardinal de Rohan, if he would transfer the scholarship to Augustin to allow him to follow the same career. The Cardinal agreed and Augustin took up his brother's place studying law.[3][4]

Although his political views were very similar to those of his brother, Augustin was very different in character. Handsome, he was also fond of good food, gaming and the company of women.[5] At the outset of the Revolution, Augustin was prosecutor-syndic of Arras.[6] He founded a political club in the town and wrote to his brother to secure its affiliation with the Jacobins in Paris.[7] In 1791, he was appointed Administrator of the département of Pas-de-Calais.

The Convention

Augustin unsuccessfully stood for election to the new Legislative Assembly in Arras in August 1791, but his views were too radical for the town, which elected another young lawyer, Sixte François Deusy instead.[8] However on 16 September 1792, Augustin was elected to the National Convention, 19th out of 24 deputies, with 392 votes out of 700 cast,[9] by the voters of Paris,[10] and he joined his brother in The Mountain and the Jacobin Club.[11] At the Convention he distinguished himself by the vehemence of his attacks on the royal family and on aristocrats. During the trial of Louis XVI he voted for the death penalty to be applied within 24 hours.[12]

When he first came to Paris to take his seat he was accompanied by his sister Charlotte, and they both lodged with Maximilien in the house of Maurice Duplay. Soon however Charlotte persuaded Maximilien to come with them to a new lodging in the rue Saint-Florentin where she could look after her two brothers. He soon returned to the Duplay's house however, leaving Augustin and Charlotte to live by themselves. However this arrangement did not last long either. A pamphlet Le souper de Beaucaire (The supper at Beaucaire) by Napoleon was read by Augustin Robespierre, who was impressed by the revolutionary context.[13] In August 1793 Augustin was sent on a mission to Alpes-Maritimes to suppress the Federalist revolt,[14] together with another deputy from the Convention, Jean François Ricord, and Charlotte accompanied him. Much of southeastern France was in rebellion against the Republic, and they barely made it alive to Nice after a very dangerous journey. In Nice they felt secure enough to attend the theatre, but on the third occasion they did so, they were pelted with rotten apples.[15] In 19 December 1793 Augustin took part in the military action, led by Dugommier and Napoleon, which retook Toulon from the British.[16] On their return to Paris, Augustin moved out of the lodging with Charlotte and went to live with Ricord and his wife.[17]

In 1794 Augustin was dispatched once again as a representant en mission, now to the Army of Italy in Haute-Saône. This time he took with him not his sister but his mistress, La Saudraye, the creole wife of a literary man.[18] He used his influence to advance Napoleon Bonaparte's career, after reading Napoleon's pro-Jacobin pamphlet titled Le souper de Beaucaire.[19][20] On his return to Paris he served as a secretary to the Convention.[21]

Death

Augustin was with his brother in the hall of the Convention on the day of 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794), when the deputies voted for the arrest of Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon after a heated discussion. Then Augustin rose from his place on the benches and said "I am as guilty as him; I share his virtues, I want to share his fate. I ask also to be charged". He was joined by Lebas.[22] The five were kept under guard in the rooms of the Committee of General Security, where they remained until a place could be found for them. Hearing of the arrests, the Commune of Paris issued orders to all prisons in the city, forbidding them to take any prisoner in, sent by the Convention. Augustin was taken to the prison of La Force while Maximilien was taken to the Luxembourg.[23] Because of the Commune's orders, they were soon released and made their way to the Hôtel de Ville. Escorted by two municipal officers Augustin was the first to arrive.[24][25] There they spent the evening vainly trying to coordinate an insurrection. In the early morning of 10 Thermidor, the forces of the Convention under Barras burst in and succeeded in taking most of them alive, except Lebas, who had shot himself and Coffinhal, who succeeded to escape, but gave himself in after a week.

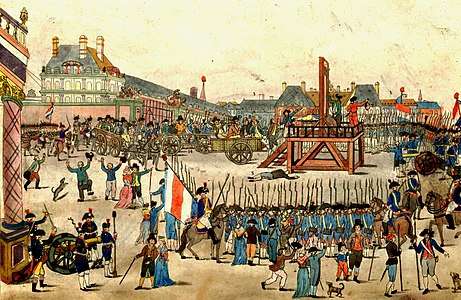

In order to avoid capture, Augustin Robespierre took off his shoes and jumped from a ledge.[26] He landed on the steps or on some bayonets resulting in a pelvic fracture and several serious head contusions, in an alarming state of "weakness and anxiety".[27] Barras ordered that Augustin to be carried back to the rooms of the Committee of General Security.[28] After a couple of hours the prisoners were taken to the Conciergerie prison; four of them were lying on stretchers. After identification at the Revolutionary Tribunal according the Law of 22 Prairial, the twenty-two convicts were sent to the scaffold on Place de la Révolution in the early evening. Couthon was the second of the prisoners to be executed, with Augustin as the third, Hanriot as the ninth and Maximilien as the tenth.[29]

References

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/%28num_dept%29/11837 accessed 17/04/2017

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 pp.17-19

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 p.31

- John Laurence Carr, Robespierre, History Book Club 1972 p.16

- Jean Martrat (trans. Alan Kendall) Robespierre, Angus & Robertson 1975 p.169

- J.M.Thompson, Robespierre, Basil Blackwell 1935 p.292

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 p.115

- Jean Matrat, Robespierre (trans. Alan Kendall) Angus & Robertson 1975 p.122

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/%28num_dept%29/11837 accessed 17 April 2017

- Vie politique de tous les députés à la Convention nationale, pendant et après la Révolution Paris 1814 p.565

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 p.208

- Vie politique de tous les députés à la Convention nationale, pendant et après la Révolution Paris 1814 p.565

- Chandler, p. 21.

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/%28num_dept%29/11837 accessed 17 April 2017

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 p.252

- Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution Vintage Books 2007 p.258

- Jean Matrat, Robespierre (trans. Alan Kendall) Angus & Robertson 1975 p.170-171

- J.M.Thompson, Robespierre, Basil Blackwell 1935, p.484

- David Chandler, Napoleon, Leo Cooper, 2002 (first published 1973) p.21

- Philip Dwyer, Napoleon: The Path to Power 1769, Bloomsbury 2007 p.136

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/%28num_dept%29/11837 accessed 17 April 2017

- J.M.Thompson, Robespierre, Basil Blackwell 1935 p.571

- Ruth Scurr (2007) A Fatal Purity, p. 320

- E. Hamel (1897) Thermidor : d'après les sources originales et les documents authentiques, p. 322

- C. Jones (2014) The Overthrow of Maximilien Robespierre and the “Indifference” of the People

- G. Lenotre (Théodore Gosselin) Arrest of Robespierre

- Lenotre, G. (1924) Robespierre's rise and fall, p. 271

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/(num_dept)/11837 accessed 17/04/2017

- Memoirs of the Sansons by H. Sanson, p. 210

Further reading

- Alexandre Cousin, Philippe Lebas et Augustin Robespierre, deux météores dans la Révolution française (2010). (in French)

- Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Sergio Luzzatto, Bonbon Robespierre: la terreur à visage humain (2010). (in French)

- Martial Sicard, Robespierre jeune dans les Basses-Alpes, Forcalquier, A. Crest (1900). (in French)

- Mary Young, Augustin, the Younger Robespierre (2011).

External links

- "L'enfance de Maximilien", in L’association Maximilien Robespierre pour l’Idéal Démocratique bulletin n° 45. (in French)