Armenian-controlled territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh

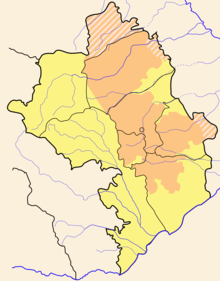

The Armenian-controlled territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh are areas de jure part of Azerbaijan and situated outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, which are since the end of the Nagorno Karabakh War controlled by the military forces of the de facto Republic of Artsakh supported by Armenia.[1]

Nomenclature

These areas have also been referred to as:

Description

Based on the administrative and territorial division of Azerbaijan, Armenian forces control the territory of the following districts of Azerbaijan:[4]

- Kalbajar - (1,936 km2,[5] 100% of which is controlled by the Artsakh Defense Army),

- Lachin - (1,835 km2.[5] - 100%),

- Qubadli - (802 km2.[5] - 100%),

- Jabrayil - (1,050 km2.[5] - 100%), excluding village Çocuk Mərcanli,

- Zangilan - (707 km2.[5] - 100%),

- Agdam - (1,094 km2.[5] - 77% (842 km2)),

- Fuzuli - (1,386 km2.[5] - 33% - 462 km2.)

The total land area is 7,634 km2. The outer perimeter of these territories is a line of direct contact between the military forces of the Republic of Artsakh and Azerbaijan.[6]

History

At the outset of the Karabakh conflict, the majority-Armenian Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast / Republic of Artsakh was surrounded by regions with Azerbaijani and Kurdish majorities and had no land border with Armenia. During the Nagorno-Karabakh war Azerbaijan had subjected Artsakh to a total blockade, which resulted in famine. As reported by the Human Rights Watch,

By the winter of 1991-92, as a result of Azerbaijan's three-year economic and transport blockade, Artsakh was without fuel…, electricity, running water, functioning sanitation facilities, communication facilities and most consumer goods.[7]

In 1992, the United States Congress added Section 907 to the Freedom Support Act of 1992, which banned direct US government support to the government of Azerbaijan. The bill namely stated:

United States assistance under this or any other Act may not be provided to the Government of Azerbaijan until the President determines that the Government of Azerbaijan is taking demonstrable steps to cease all blockades and other offensive uses of force against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.[8]

On 24 October 2001 the Senate adopted an amendment that would provide the President with the ability to waive Section 907,[9] and he has done so since then.

- 18 May 1992, Armenian forces took Lachin, opening the Lachin corridor for land communications between NKR and Armenia. However, the corridor was under constant threat from Azerbaijani forces who repeatedly tried to cut it. A strong offensive by Armenian forces occurred in 1993, resulting in the securing of further territory to act as a "security zone".

- 27 March 1993, Armenian forces launched an offensive in Kelbajar and by 5 April had completely captured the area of Kalbajar Rayon, creating a strong link between Nagorno Karabakh and Armenia and removing from the Lachin corridor the threat of attack from the north.

- 23 July 1993, after 40 days of fighting, officially known in Armenia as the "suppression of enemy firing points", Agdam was taken. Then followed attack in the south:

- 22 August 1993 Fizuli was taken.

- 25 August 1993 - Jebrail was taken.

- 31 August 1993 - Kubatly was taken.

- 1 November 1993 - Zangelan was taken.

During this phase of the war, Azerbaijan would not agree to sign a ceasefire until after these territories passed under the Armenian control and there was a danger that Armenians would advance further to take territories of vital importance for Azerbaijan.[10][11] As described by Russian mediator Vladimir Kazimirov,

Azerbaijan for too long a time was counting on military solution of the problem… those who for more than a year (1993-1994) ignored the UN Resolutions that called for the ceasefire… were supposed to realise their direct responsibility for the consequences – for the loss of more regions and the increasing the number of refugees and IDPs.[10]

Since then, Armenians have been in control of most of the territory of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, with Azerbaijan controlling parts of east Martuni and east Martakert. In addition, since that time, Armenians have controlled all of the territory between the former NKAO to Iran, as well as all of the territory between the former NKAO and Armenia, and some areas to the east surrounding Aghdam. Nagorno-Karabakh also claims but does not control the region known until 1992 as Shahumian, which although being majority-Armenian before 1992, was not part of the NKAO. Shahumian's Armenian population was driven out during the war, and the Armenian and Azeri forces have been separated on the northern front by the Murovdag mountain chain ever since.[12]

Since 1994, Armenia and Azerbaijan have held talks on the future of the security belt territories. The Republic of Artsakh has not been involved in these negotiations because Azerbaijan does not recognize the existence of such parties to the conflict. The Armenian side has offered to act in accordance with the "land for status" formula (returning the territory of the security belt to the control of Azerbaijan in exchange for Azerbaijan recognizing the independence of the Republic of Artsakh and giving security assurances to the Republic of Artsakh and the Lachin corridor),[13] Azerbaijan, on a formula of "land for peace" (returning the territory of the security belt back to Azerbaijan in exchange for security guarantees with Azerbaijan controlling territories of Nagorno-Karabakh). Facilitators have also offered, in particular, another "land for status" option (returning the territory of the security belt to the control of Azerbaijan in exchange for guarantees by Azerbaijan to hold at some point a referendum on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh).[14] The involved parties have failed to reach any agreement.

Legal status

- From the standpoint of the Republic of Artsakh, the security belt is territory of Azerbaijan temporarily controlled by the Artsakh Defense Army until the receipt of security guarantees for the Republic of Artsakh and the establishment of control over the whole of the territory declared by the Republic of Artsakh, with the exception of the Lachin corridor linking Artsakh with Armenia (which the Republic of Artsakh has stated it does not intend to return because of its strategic importance) [15][16] (currently Azerbaijan controls 750 km2 of territory claimed by the Nagorno Karabakh Republic[17] - Shahumian (630 square kilometers[5]) and a small part of Martuni and Mardakert areas, representing 14.85% of the total area of NKR). According to Article 142 of the Constitution of the Republic of Artsakh "to restore the integrity of national territory of the Republic of Artsakh and clarifying boundaries public power is exercised in the territory actually under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Artsakh",[16] that is, including the territory of Azerbaijan, outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and Shaumian district, which borders was proclaimed Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh.[15]

- From the standpoint of Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh and 7 adjacent districts are a territory occupied by Armenia.[18]

- In the documents of international organizations (such as the United Nations, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe), these areas are also considered as occupied by "Armenian forces",[19][20][21][22] but there are recognized two entities on the Armenian side of the conflict: The Republic of Armenia and "Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan"[21][22] (in terms of PACE - "Separatist forces"[20]).

Armenian historical monuments

Some Armenian sources use the term "liberated territories", emphasising Armenian historical and religious monuments in the area and the presence of an Armenian population since 350BC.

Some of the historical and religious monuments of note in these territories:

- Dadivank Monastery, (Armenian: Դադիվանք)[23] - an Armenian monastery in the Shahumian Region (former Kelbajar), built between the 9th and 13th centuries. The monastery was founded by St. Dadi, a disciple of Thaddeus the Apostle who spread Christianity in Eastern Armenia during the first century A.C. In June, 2007, the grave of St. Dadi was discovered under the holy altar of the main church.[24]

- Tzitzernavank Monastery, (Armenian: Ծիծեռնավանք), a fifth- to sixth-century[25] Armenian church[26] and former monastery. The monastery is within five kilometers of the border of Armenia's province of Syunik. The basilica of Tzitzernavank was believed to contain relics of St. George the Dragon-Slayer. In the past, the monastery belonged to the Tatev diocese and is mentioned as a notable religious center by the 13th century historian Stepanos Orbelian and Bishop Tovma Vanandetsi (1655).

- Handaberd Fortress, (Armenian: Հանդաբերդ): Armenian castle and fortress, built in the 11th century, that belonged to the rulers of the Kingdom of Upper Khachen and the Kingdom of Tzar.,[27]

- Handaberd Monastery, (Armenian: Հանդաբերդ): An Armenian Monastery that belonged to the rulers of the Kingdom of Upper Khachen and the Kingdom of Tzar, built in 1276.

- Tigranakert, (Armenian: Տիգրանակերտ) - ruins of an ancient Armenian city near the borders of NKR's Mardakert district, dating back to the Hellenistic period. It is one of several cities on the Armenian plateau named Tigranakert in honor of the Armenian king Tigranes the Great (r. 95–55 B.C.).[28][29] Tigranakert was uncovered during the excavations which began in 2005.[30]

References

- Нужны ли российские миротворцы в Нагорном Карабахе (in Russian)

Human Rights Watch. Playing the "Communal Card". Communal Violence and Human Rights. ("By early 1992 full-scale fighting broke out between Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians and Azerbaijani authorities.") / ("...Karabakh Armenian forces -often with the support of forces from the Republic of Armenia- conducted large-scale operations...") / ("Because 1993 witnessed unrelenting Karabakh Armenian offensives against the Azerbaijani provinces surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh...") / ("Since late 1993, the conflict has also clearly become internationalized: in addition to Azerbaijani and Karabakh Armenian forces, troops from the Republic of Armenia participate on the Karabakh side in fighting inside Azerbaijan and in Nagorno-Karabakh.")

Human Rights Watch. The former Soviet Union. Human Rights Developments. ("In 1992 the conflict grew far more lethal as both sides -the Azerbaijani National Army and free-lance militias fighting along with it, and ethnic Armenians and mercenaries fighting in the Popular Liberation Army of Artsakh- began...")

United States Institute of Peace. Nagorno-Karabakh Searching for a Solution. Foreword. Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine ("Nagorno-Karabakh’s armed forces have not only fortified their region, but have also occupied a large swath of surrounding Azeri territory in the hopes of linking the enclave to Armenia.")

United States Institute of Peace. Sovereignty after Empire. Self-Determination Movements in the Former Soviet Union. Hopes and Disappointments: Case Studies. Archived 11 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine ("Meanwhile, the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh was gradually transforming into a full-scale war between Azeri and Karabakh irregulars, the latter receiving support from Armenia.") / ("Azerbaijan's objective advantage in terms of human and economic potential has so far been offset by the superior fighting skills and discipline of Nagorno-Karabakh's forces. After a series of offensives, retreats, and counteroffensives, Nagorno-Karabakh now controls a sizable portion of Azerbaijan proper (...), including the Lachin corridor.") - Report of the OSCE Minsk Group Co-Chairs' Field Assessment Mission to the Occupied Territories of Azerbaijan Surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh

"UN Security Council Resolution 822 (30 April 1993)".Demands the immediate cessation of all hostilities and hostile acts with a view to establishing a durable cease-fire, as well as immediate withdrawal of all occupying forces from the Kelbadjar district and other recently occupied areas of Azerbaijan

"UN Security Council Resolution 853 (29 July 1993)".Demands the immediate cessation of all hostilities and the immediate complete and unconditional withdrawal of the occupying forces involved from the district of Agdam and all other recently occupied areas of the Azerbaijan Republic

"UN Security Council Resolution 884 (12 November 1993)".Demands from the parties concerned the immediate cessation of armed hostilities and hostile acts, the unilateral withdrawal of occupying forces from the Zangelan district and the city of Goradiz, and the withdrawal of occupying forces from other recently occupied areas of the Azerbaijani Republic

- Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A Historical Atlas. The University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 264. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4

Thomas de Waal. Armenia’s Crisis and the Legacy of Victory ("In defiance of the fact that these regions are internationally recognised de jure parts of Azerbaijan that were never part of the original dispute over Karabakh, the radicals refer to these captured territories as “liberated” lands.") - Адекватному пониманию армяно-азербайджанского конфликта мешает распространение и повторение ложной статистики (in Russian)

- Азербайджанская ССР - Административно-территориальное деление (in Russian). Baku: Azgoisdat (Азгоиздат). 1979.

- Вооруженное противостояние на Южном Кавказе (in Russian)

- Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (1992) Bloodshed in the Caucasus: escalation of the armed conflict in Nagorno Karabakh. New York: Human Rights Watch, p. 12

- Freedom Support Act (1992) Section 907: Restrictions on the Assistance to Azerbaijan. Public Law 102-511, Washington DC, 24 October 1992.

- Public Law 107-115

- Kazimirov Vladimir (2007) Есть ли выход из тупика в Карабахе? [Is there a way out from the deadlock in Karabakh?] Russia in Global Politics, no. 5, 27 Oct. 2007

- Patrick Wilson Gore 2008. 'Tis some poor fellow's skull: post-Soviet warfare in the southern Caucasus

- Приднестровье и Нагорный Карабах — два состоявшихся самодостаточных государства (in Russian)

- Контролируемые карабахской стороной территории могут быть возвращены Азербайджану лишь в обмен на независимость НКР -дептутат (in Russian)

- Дартмутская конференция (in Russian)

Ереван «сдает» Карабах и спешит в объятия НАТО (in Russian)

Визит действующего председателя ОБСЕ Дмитрия Рупеля Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

Препятствия на пути к урегулированию: взгляд из Азербайджана Archived 11 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

Земля преткновения(in Russian). 25 October 2009.

Переговоры по Карабаху: внимание переключается на президента Алиева (in Russian)

«Сатана» раскрывает «детали», а «они не нужны нам и подавно»: политики Армении и Карабаха о возможности сдачи территорий (in Russian) - Декларация о провозглашении Нагорно-Карабахской Республики (in Russian)

- Конституция Нагорно-Карабахской республики Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

Т. де Ваал. Черный сад. Ни войны, ни мира. Глава 17 (in Russian) - Жители Нагорного Карабаха до сих пор подрываются на минах (in Russian)

- Президент Азербайджана: мы продолжим изоляцию Армении и будем наращивать военную мощь (in Russian)

- Резолюция СБ ООН 822 (1993) от 30 апреля 1993 годa (in Russian)

Резолюция СБ ООН 822 (1993) от 30 апреля 1993 годa. Un.org. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Резолюция СБ ООН 874 (1993) от 14 октября 1993 годa (in Russian)

Рекомендация ПАСЕ № 1263 (1995). Assembly.coe.int (15 March 1995). Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Доклад ПАСЕ № 7250 (1995). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Доклад ПАСЕ № 7260 (1995). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Резолюция ПАСЕ № 1059 (1995). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Резолюция ПАСЕ № 1119 (1997). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Доклад № 7793 (1997). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Рекомендация № 1335 (1997). Assembly.coe.int (24 June 1997). Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Доклад ПАСЕ № 7837 (1997). Council of Europe. Retrieved on 6 January 2012.

Рекомендация ПАСЕ № 1570 (2002) (in Russian)

Доклад ПАСЕ № 10364 (2004) (in Russian) - Резолюция ПАСЕ № 1416 (2005) (in Russian)

- Резолюция СБ ООН 853 (1993) от 29 июля 1993 годa (in Russian)

- Резолюция СБ ООН 884 (1993) от 12 ноября 1993 годa (in Russian)

- Le Petit Futé Arménie – by Dominique Auzias, Jean-Paul Labourdette – 2009

- В старинном монастыре Нагорного Карабаха обнаружены мощи одного из учеников Иисуса Христа

- Turner, Jane (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 2003, p. 425. ISBN 0-19-517068-7.

- Kouymjian, Dickran. "Index of Armenian Art: Armenian Architecture - Tsitsernavank". Armenian Studies Program. California State University, Fresno. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- Sir Henry Hoyle Howorth. History of the Mongols. Volume 3. p. 86

- Petrosyan, Hamlet L. "Tigranakert in Artsakh," in Tigranes the Great. Yerevan, 2010, pp. 380-87.

- Harutyunyan, Arpi. "Research in Ruins: Tigranakert project threatened by lack of finances." ArmeniaNow. April 11, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- "Museum at Ancient Ruins of Tigranakert Opens in Nagorno-Karabakh." Asbarez. June 8, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.