Armée indigène

The Indigenous Army (French: Armée Indigène), also known as the Army of Saint-Domingue (French: Armée de Saint-Domingue), was the group of gens de couleur, free blacks; affranchi, mullatos; and basal slaves that fought in the Haitian Revolution [6]. They were not officially called the Armée Indigène until January 1803, under the leadership of Dessalines [3]. Led by famous leaders such as Vincent Ogé, Toussaint Louverture, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the Armée Indigène would consolidate their power and fight using guerilla tactics to make the Haitian Revolution the first successful revolution of its kind.

Pre-Haitian Revolution

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, Haiti, called Saint-Domingue before the Haitian Revolution, was a valuable French colony in the West Indies that produced most of the world's sugar and coffee[6]. To take advantage of the economic benefits of this colony, the French established a plantation system, like the one used by the plantation owners in the South. There, the slaves of the Armée Indigène would be forced to endure cruel living conditions under the Code Noir; diseases such as yellow fever would run rampant, and the death rate of slaves was so high that plantation owners, the grands blancs, would expose them to even worse conditions that lacked food and shelter, to save money (since they would die regardless)[3][4][5]. While banned, the only consolation of the slaves was Voodoo, a religion that incorporated West African beliefs [4][6][10]. Despite their free status, the gens de couleur were not safe from the discrimination that resulted from their skin color; petits blancs (poor whites) held resentment towards them because of their wealth and ability to buy other slaves.

In 1789, The Declaration of the Rights of Man gave hope to the gens de couleur that they would have better living conditions and rights that they did not have, especially now that France would look at every citizen equally, regardless of position or race[7]. However, the vague interpretation of the Declaration would leave the African Americans unchanged in terms of social position; in fact, the grand blancs would take advantage of the Declaration and use it to gain independence from trade regulations. In addition, slavery was not officially abolished. Since the 1780s, free men of color such as Julien Raimond and Vincent Oge had tried to get African Americans the rights that belonged to them by representing the colonies in the National Assembly. One of these rights was the right to vote; however, the African Americans were still denied of this right. With 300 armed gens de couleur and affranchis, Vincent Oge led an insurrection of African Americans, which attempted to disarm the white men of Grande-Rivière[1][8]. Taking place in 29 October 1790, this event became known as the Oge Rebellion, which ended up in a failure. Oge and his rebels were executed on the wheel, and his barbaric death would cause even more tension amongst African Americans, who already had the mindset of revolution[1][8].

Haitian Revolution

The wealthy gen de couleur were given citizenship in May 1791, which caused tension between them and the grands blancs, and as a result, fighting broke out between the two groups. Because of this, the poorer African Americans like the slaves were also resentful of grands blancs, who were in the way of what was the beginning of equality for everyone in Saint-Domingue. The first rebellion broke out in August 1791, when religious Voodoo priest Dutty Boukman ordered the slaves to attack Bois Caïman[4]. While they were seeking their rights as Frenchmen, the slaves also engaged in acts of cruelty, such as rape and murder against the white plantation owners. In a couple of weeks, the number of slaves participating in the rebellion was over 100,000. By 1792, a third of Saint-Domingue was under the control of the slaves, and France was ready to quell the rebellion[9]. They gave political rights to the gen de couleur, and sent Léger-Félicité Sonthonax to Saint-Domingue as its new governor; he was a man against slavery and the plantation owners[4]. While all of this was happening, Toussaint Louverture was training his own army in the ways of guerilla warfare, and helping the Spanish, who declared war against France in 1793; both the Spaniards and the British were helping the rebels in hopes that they could take over Saint-Domingue and use its resources. Louverture, alongside Dessalines and his army, would go back to the French in 1794, a while after France abolished slavery in the colonies [1][2]. Later, Louverture would establish a Haitian constitution and declare himself governor for life, but Napoleon Bonaparte did not accept this claim, and locked up Louverture, where he would die in prison[1][2]. In 1803. Dessalines took over, and by then, the army that fought in the Haitian Revolution was renamed as the Armée Indigène. Saint-Domingue's flag changed to a red and blue flag with the slogan “Liberte a la Mort” (Liberty or Death) in white lettering [3]. Bonaparte would try to reestablish the slave regime by sending general Charles Leclerc to Saint-Domingue, but would fail to stop the Armée Indigène, because of an outbreak of yellow fever[4][10]. Because of this, the Armée Indigène was now known as the army that freed Saint-Domingue.

Casualties and Lasting Impact

While the actions of the Armée Indigène were fueled by Enlightenment principles that advocated for the equality of all Frenchmen, the Haitian Revolution had many casualties; both sides suffered losses from their own violence. The Haitians suffered about 200,000 casualties, which made them the group that lost the most. The British and French together suffered about 120,000 casualties. Dessalines would later be known for the 1804 massacre of the French, which lasted for 2 months and even affected innocents like women and children.

However, despite the violence that occurred, the actions of the Armée Indigène in the Haitian Revolution would serve as inspiration to the slaves in the United States, as Haiti would finally be recognized by France in 1825, and later by the United States, in 1862[10].

List of generals

Commanders-in-chief

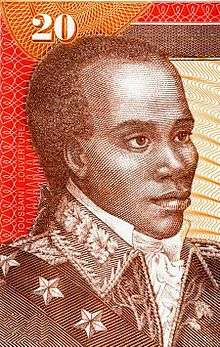

- Toussaint Louverture, Commander-in-chief (1793-180, governor-general of Saint-Domingue 1801-1803)

- Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Commander-in-chief (1803-1804, first president and later emperor of Haiti)

Division generals

- Henri Christophe

- Alexandre Pétion

- Augustin Clervaux

- Nicolas Geffrard

- Andre Vernet

- Louis Gabart

Brigadier-generals

- Paul Romain

- Étienne Élie Gerin

- François Capois

- Daut

- Jean-Louis François,

- Laurent Férou

- Pierre Cangé

- L. Bazelais

- Magloire Ambroise

- J. J. Herne,

- Toussaint-Brave

- Yayou

Other generals

- Jacques Maurepas

- Jean-François Papillon

- Georges Biassou

- Jeannot Bullet

- Louis Michel Pierrot

- Hyacinthe Moïse

- Joseph Balthazar Inginac

Adjutants-general

- Guy-Joseph Bonnet

Officers

- Nicolas Pierre Mallet

References

- "Case Study 1: St. Domingue - Vincent Oge & Toussaint l'Ouverture." Case Study 1: St. Domingue - Vincent Oge & Toussaint l'Ouverture: The Abolition of Slavery Project. Accessed February 22, 2018. http://abolition.e2bn.org/resistance_47.html

- Fagg, John E. "Toussaint Louverture." Encyclopædia Britannica. December 18, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Toussaint-Louverture.

- Fombrun, Odette Roy. "HISTORY OF THE HAITIAN FLAG OF INDEPENDENCE." Flag Heritage Foundation.org. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20160304033712/http://www.flagheritagefoundation.org/web/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/history-of-the-haitian-flag-of-independence.pdf.

- "Haitian Revolution." Wikipedia. February 20, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Jackson, Maurice, and Jacqueline Bacon. African Americans and the Haitian revolution selected essays and historical documents. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

- Lawless, Robert, and James A. Ferguson. "Haiti." Encyclopædia Britannica. February 7, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/place/Haiti/Early-period#ref54483.

- McPhee, Peter. LIBERTY OR DEATH. S.l.: Yale Univ Press, 2017.

- Shen, Kona. "Haitian Revolution Begins August–September 1791." The Haitian Revolution 1791. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://library.brown.edu/haitihistory/5.htm%5B%5D

- Steward, T. G. The Haitian revolution, 1791 to 1804; or, Side lights on the French Revolution. New York: Russell & Russell, 1971.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "Haitian Revolution." Encyclopædia Britannica. December 28, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Haitian-Revolution.

External links

(Picture of Dessalines is named Huyes del valor frances, pero matando blancos, by Manuel Lopes Lopez Iodibo. It is an engraving in the book Vida de J.J. Dessalines, gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo and is located in the John Carter Brown Library)

(Picture of Toussaint Louverture is named Le général Toussaint Louverture. The artist is unknown, and it is currently in the New York Public Library)