Apocolocyntosis

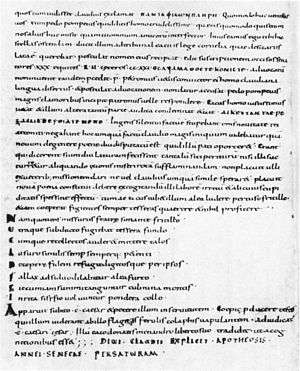

The Apocolocyntosis (divi) Claudii, literally The pumpkinification of (the Divine) Claudius, is a satire on the Roman emperor Claudius, which, according to Cassius Dio, was written by Seneca the Younger. A partly extant Menippean satire, an anonymous work called Ludus de morte Divi Claudii ("Play on the death of the Divine Claudius") in its surviving manuscripts, may or may not be identical to the text mentioned by Cassius Dio. "Apocolocyntosis" is a word play on "apotheosis", the process by which dead Roman emperors were recognized as gods.

Authorship

The Ludus de morte Divi Claudii is one of only two examples of a Menippean satire from the classical era that have survived, the other being Satyricon, which was likely written by Petronius. Gilbert Bagnani is among the scholars who also attribute the Ludus text to Petronius.[1]

"Apocolocyntosis" is Latinized Greek, and can also be transliterated as Apokolokyntosis (Attic Greek Ἀποκολοκύντωσις: "Pumpkinification", also "Gourdification"). The title Apokolokyntosis comes from the Roman historian Cassius Dio, who wrote in Greek. Cassius Dio attributed authorship of a satirical text on the death of Claudius, called Apokolokyntosis, to Seneca the Younger.[2] Only much later was the work referred to by Cassius Dio identified (with some degree of uncertainty) with the Ludus text.[3] Most scholars accept this attribution, but a minority hold that the two works are not the same, and that the surviving text is not necessarily Seneca's.[4]

Seneca had some personal reason for satirizing Claudius, because the emperor had banished him to Corsica. In addition, the political climate after the emperor's death may have made attacks on him acceptable. However, alongside these personal considerations, Seneca appears also to have been concerned with what he saw as an overuse of apotheosis as a political tool. If an emperor as flawed as Claudius could receive such treatment, he argued elsewhere, then people would cease to believe in the gods at all. A reading of the Ludus text shows that its author was not above flattery of the new emperor Nero – such as writing that he would live longer and be wiser than the legendary Nestor.

Plot

The work traces the death of Claudius, his ascent to heaven and judgment by the gods, and his eventual descent to Hades. At each turn, of course, Seneca mocks the late emperor's personal failings, most notably his arrogant cruelty and his inarticulacy. After Mercury persuades Clotho to kill the emperor, Claudius walks to Mount Olympus, where he convinces Hercules to let the gods hear his suit for deification in a session of the divine senate. Proceedings are in Claudius' favor until Augustus delivers a long and sincere speech listing some of Claudius' most notorious crimes. Most of the speeches of the gods are lost through a large gap in the text. Mercury escorts him to Hades. On the way, they see the funeral procession for the emperor, in which a crew of venal characters mourn the loss of the perpetual Saturnalia of the previous reign. In Hades, Claudius is greeted by the ghosts of all the friends he has murdered. These shades carry him off to be punished, and the doom of the gods is that he should shake dice forever in a box with no bottom (gambling was one of Claudius' vices): every time he tries to throw the dice they fall out and he has to search the ground for them. Suddenly Caligula turns up, claims that Claudius is an ex-slave of his, and hands him over to be a law clerk in the court of the underworld.

See also

- Imperial cult (Ancient Rome)

Notes

- Gilbert Bagnani. Arbiter of Elegance: A study of the Life & Works of C. Petronius (1954)

- "Seneca himself had composed a work that he called Gourdification,—a word made on the analogy of 'deification'" (Dio Cassius, Book 61, No. 35 - Translation by Herbert Baldwin Foster, 1905, retrieved from Project Gutenberg)

- See introduction of W. H. D. Rouse's translation: "This piece is ascribed to Seneca by ancient tradition; it is impossible to prove that it is his, and impossible to prove that it is not. The matter will probably continue to be decided by every one according to his view of Seneca's character and abilities: in the matters of style and of sentiment much may be said on both sides. Dion Cassius (lx, 35) says that Seneca composed an "apokolokintosis" or Pumpkinification of Claudius after his death, the title being a parody of the usual "apotheosis"; but this title is not given in the MSS. of the Ludus de Morte Claudii, nor is there anything in the piece which suits the title very well."

- Clausen, W. V.; Kenney, E. J. The Cambridge History of Classical Literature. 2. p. 137. ISBN 0521273722.

References

- Altman, Marion (1938). "Ruler Cult in Seneca." Classical Philology 33 (1938): 198–204.

- Astbury, Raymond (1988). "The Apocolocyntosis." The Classical Review ns 38 (1988): 44–50.

- Colish, Marcia (1976). "Seneca's Apocolocyntosis as a Possible Source for Erasmus' Julius Exclusus." Renaissance Quarterly 29 (1976): 361–368.

- Relihan, Joel (1984). "On the Origin of 'Menippean Satire' as the Name of a Literary Genre." Classical Philology 79 (1984): 226–9.

- Translations

- At Project Gutenberg: E-text No. 10001, English translation of the Apocolocyntosis by W. H. D. Rouse, 1920

- Claudius the God, by Robert Graves contains a translation of the Apocolocyntosis in the annexes.

- J.P. Sullivan (ed), "The Apocolocyntosis" (Penguin Books, 1986) ISBN 978-0-14-044489-6