American chestnut

The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a large, monoecious deciduous tree of the beech family native to eastern North America.[2] The American chestnut was once considered one of the most important forest trees throughout its range and was considered the finest chestnut tree in the world.[3][4] However, the species was devastated by chestnut blight, a fungal disease that came from introduced chestnut trees from East Asia. It is estimated that between 3 and 4 billion American chestnut trees were destroyed in the first half of the 20th century by blight after its initial discovery in 1904.[5][6][7] Very few mature specimens of the tree exist within its historical range, although many small shoots of the former live trees remain. There are hundreds of large (2 to 5 ft diameter) American chestnuts outside its historical range, some in areas where less virulent strains of the pathogen are more common, such as the 600 to 800 large trees in Northern Michigan.[8][9] The species is listed as endangered in Canada as well as in the United States.[10][11] Chinese chestnut trees have been found to have the highest resistance/immunity to chestnut blight[12][13][14][15], therefore there are currently programs to revive the American chestnut tree population by cross-breeding the blight-resistant Chinese chestnut with the American chestnut tree, so that the blight-resistant genes from Chinese chestnut may protect and restore the American chestnut population back to its original status as a dominant species in American forests.[12][13][14][15]

| American chestnut | |

|---|---|

| American chestnut leaves and nuts | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Castanea |

| Species: | C. dentata |

| Binomial name | |

| Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh. | |

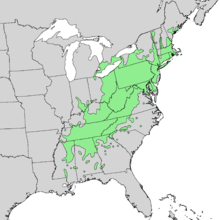

| |

| Natural range of Castanea dentata | |

Description

Castanea dentata is a rapidly growing deciduous hardwood tree, historically reaching up to 30 metres (98 ft) in height, and 3 metres (9.8 ft) in diameter. It ranged from Maine and southern Ontario to Mississippi, and from the Atlantic coast to the Appalachian Mountains and the Ohio Valley. C. dentata was once one of the most common trees in the Northeastern United States. In Pennsylvania alone, it is estimated to have comprised 25–30% of all hardwoods. The tree's huge population was due to a combination of rapid growth and a large annual seed crop in comparison to oaks which do not reliably produce sizable numbers of acorns every year. Nut production begins when C. dentata is 7–8 years old.

There are several similar chestnut species, such as the European sweet chestnut, Chinese chestnut, and Japanese chestnut. The American species can be distinguished by a few morphological traits, such as leaf shape, petiole length and nut size. For example, it has larger and more widely spaced saw-teeth on the edges of its leaves, as indicated by the scientific name dentata, Latin for "toothed". According to a 1999 study by American Society for Horticultural Science, the Ozark chinkapin, which is typically considered either a distinct species (C. ozarkensis) or a subspecies of the Allegheny chinkapin (C. pumila ozarkensis) may be ancestral to both the American chestnut and the Allegheny chinkapin.[16][17]

The leaves, which are 14–20 cm (5.5–8 in) long and 7–10 cm (3–4 in) broad, also tend to average slightly shorter and broader than those of the sweet chestnut. The blight-resistant Chinese chestnut is now the most commonly planted chestnut species in the US, while the European chestnut is the source of commercial nuts in recent decades. It can be distinguished from the American chestnut by its hairy twig tips which are in contrast to the hairless twigs of the American chestnut. The chestnuts are in the beech family along with beech and oak, but are not closely related to the horse-chestnut, which is in the family Sapindaceae.

The chestnut is monoecious, producing many small, pale green (nearly white) male flowers found tightly occurring along 6 to 8 inch long catkins. The female parts are found near base of the catkins (near twig) and appear in late spring to early summer. Like all members of the family Fagaceae, American chestnut is self-incompatible and requires two trees for pollination, which can be any member of the Castanea genus.

The American chestnut is a prolific bearer of nuts, usually with three nuts enclosed in each spiny, green burr, and lined in tan velvet. The nuts develop through late summer, with the burrs opening and falling to the ground near the first fall frost.

The American chestnut was a very important tree for wildlife, providing much of the fall mast for species such as white-tailed deer and wild turkey and, formerly, the passenger pigeon. Black bears were also known to eat the nuts to fatten up for the winter. The American chestnut also contains more nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium in its leaves when compared to other trees that share its habitat. This means they return more nutrients to the soil which helps with the growth of other plants, animals, and microorganisms.[18]

Chestnut blight

Once an important hardwood timber tree, the American chestnut suffered a substantial population collapse due to the chestnut blight, a disease caused by an Asian bark fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica, formerly Endothia parasitica). This disease was accidentally introduced into North America on imported Asiatic chestnut trees. Chestnut blight was first noticed on American chestnut trees in what was then the New York Zoological Park, now known as the Bronx Zoo, in the borough of The Bronx, New York City, in 1904, by chief forester Hermann Merkel. Merkel estimated that by 1906 blight had infected 98 percent of the chestnut trees in the borough.[19] While Chinese chestnut evolved with the blight and developed a strong resistance, the American chestnut had little resistance. The airborne bark fungus spread 50 mi (80 km) a year and in a few decades girdled and killed up to three billion American chestnut trees. Salvage logging during the early years of the blight may have unwittingly destroyed trees which had high levels of resistance to this disease and thus aggravated the calamity.[6] New shoots often sprout from the roots when the main stem dies, so the species has not yet become extinct. However, the stump sprouts rarely reach more than 6 m (20 ft) in height before blight infection returns, which therefore, is classified as functionally extinct[20] since the Chestnut Blight only actively kills the above ground portion of the American Chestnut tree, leaving behind the below ground components such as the root systems. It was recorded in the 1900s that the chestnut blight would commonly reinfect any novel stems that grew from the stumps of the American Chestnut tree and therefore maintained a cycle that would prevent the American Chestnut tree from re-establishing.[21] Despite the chestnut blight, some American Chestnut trees have survived due to having a small natural resistance to the chestnut blight.[22]

Prior to chestnut blight occurring, an epidemic of ink disease struck American chestnuts in the early 19th century. This pathogen, apparently introduced from Europe, where it affects C. sativa, kills the tree's roots and collars. It affected primarily chestnuts in the Southeastern US and at the time when chestnut blight struck, the range of C. dentata may have already been reduced.

Reduced population

The total number of chestnut trees in eastern North America was estimated at over three billion, and 25% of the trees in the Appalachian Mountains were American chestnut. The number of large surviving trees over 60 cm (24 in) in diameter within its former range is probably fewer than 100. American chestnuts were also common part of the forest canopy in southeast Michigan.[23]

Although large trees are currently rare east of the Mississippi River, it exists in pockets in the blight-free West, where the habitat was agreeable for planting: settlers took seeds for American chestnut with them in the 19th century. Huge planted chestnut trees can be found in Sherwood, Oregon, as the Mediterranean climate of the West Coast discourages the fungus, which relies on hot, humid summer weather. American chestnut also thrives as far north as Revelstoke, British Columbia.

At present, it is believed that survival of C. dentata for more than a decade in its native range is almost impossible. The fungus uses various oak trees as a host,[24] and while the oak itself is unaffected, American chestnuts nearby will succumb to the blight in approximately a year or more.[25] In addition, the hundreds of chestnut stumps and "living stools" dotting eastern woodlands may still contain active pathogens.

Attempts at revitalization

Several organizations are attempting to breed blight-resistant chestnut trees. The American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation breeds surviving American chestnuts, which have shown some native resistance to blight, and the Canadian Chestnut Council is attempting to reintroduce the trees in Canada, primarily in Ontario. A technique called backcrossing is being used by The American Chestnut Foundation in an attempt to restore the American chestnut to its original habitat.

Intercrossing surviving American chestnuts

American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation (ACCF) is not using Oriental genes for blight resistance, but intercrossing among American chestnuts selected for native resistance to the blight, a breeding strategy described by the ACCF as "All-American intercrosses". John Rush Elkins, a research chemist and professor emeritus of chemistry at Concord University, and Gary Griffin, professor of plant pathology at Virginia Tech, think there may be several different characteristics which favor blight resistance. Both Elkins and Griffin have written extensively about the American chestnut.[26] They believe that by making intercrosses among resistant American chestnuts from many locations, they will continue to improve upon the levels of blight resistance to make an American chestnut that can compete in the forest. Griffin, who has been involved with American chestnut restoration for many years,[26] developed a scale for assessing levels of blight resistance, which made it possible to make selections scientifically. He inoculated five-year-old chestnuts with a standard lethal strain of the blight fungus and measured growth of the cankers. Chestnuts with no resistance to blight make rapid-growing, sunken cankers that are deep and kill tissue right to the wood. Resistant chestnuts make slow-growing, swollen cankers that are superficial: live tissue can be recovered under these cankers. The level of blight resistance is judged by periodic measurement of cankers. Grafts from large survivors of the blight epidemic were evaluated following inoculations, and controlled crosses among resistant American chestnut trees were made beginning in 1980. The first "All-American intercrosses" were planted in Virginia Tech's Martin American Chestnut Planting in Giles County, Virginia, and in Beckley, West Virginia. They were inoculated in 1990 and evaluated in 1991 and 1992. Nine of the trees showed resistance equal to their parents, and four of these had resistance comparable to hybrids in the same test.[26][27][28][29] Many ACCF chestnuts have expressed blight resistance equal to or greater than an original blight survivor but so far, only a handful have demonstrated superior, durable blight control. Time will tell if the progeny of these best chestnuts exhibit durable blight resistance in different stress environments.[30]

Backcrossing

Backcrossing as a treatment for blight was first proposed by Charles R. Burnham of the University of Minnesota in the 1970s.[5][7][31] Burnham, a professor emeritus in agronomy and plant genetics who was considered one of the pioneers of maize genetics,[32] realized that experiments conducted by the USDA to cross-breed American chestnuts with European and Asian chestnuts erroneously assumed that a large number of genes were responsible for blight resistance, while it is currently believed the number of responsible genes is low. The USDA abandoned their cross-breeding program and destroyed local plantings around 1960 after failing to produce a blight-resistant hybrid.[33] Burnham's recognition of the USDA's error led to him joining with others to create The American Chestnut Foundation in 1983, with the sole purpose of breeding a blight-resistant American chestnut.[31] The American Chestnut Foundation is backcrossing blight-resistant Chinese chestnut into American chestnut trees, to recover the American growth characteristics and genetic makeup, and then finally intercrossing the advanced backcross generations to eliminate genes for susceptibility to blight.[34] The first backcrossed American chestnut tree, called "Clapper", survived blight for 25 years, and grafts of the tree have been used by The American Chestnut Foundation since 1983.[33] The Pennsylvania chapter of The American Chestnut Foundation, which seeks to restore the American chestnut to the forests of the Mid-Atlantic states, has planted over 22,000 trees.[35]

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 requires owners of abandoned coal mines to cover at least 80 percent of their land with vegetation. While many companies planted invasive grasses, others began funding research on planting trees, because they can be more cost-effective, and yield better results.[36] Keith Gilland began planting American chestnut trees in old strip mines in 2008 as a student at Miami University, and to date has planted over 5,000 trees.[36] In 2005, a hybrid tree with mostly American genes was planted on the lawn of the White House.[37] A tree planted in 2005 in the tree library outside the USDA building was still very healthy seven years later; it contains 98% American chestnut DNA and 2% Chinese chestnut DNA. This tree contains enough Chinese chestnut DNA that encodes for systemic resistance genes to resist the blight. This is essential for restoring the American chestnut trees into the Northeast.[38] The Northern Nut Growers Association (NNGA) has also been active in pursuing viable hybrids.[39] From 1962 to 1990, Alfred Szego and other members of the NNGA developed hybrids with Chinese varieties which showed limited resistance. Initially the backcrossing method would breed a hybrid from an American Chestnut nut and a Chinese Chestnut, the hybrid would then be bred with a normal American Chestnut, subsequent breeding would involve a hybrid and an American Chestnut or two hybrids, which would increase the genetic makeup of the hybrids primarily American Chestnut but still retain the blight resistance of the Chinese Chestnut[40]

Transgenic blight-resistant American chestnut

Researchers at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF), have developed partially blight-resistant transgenic American chestnuts that are capable of surviving infection by Cryphonectria parasitica.[41] This was done by inserting a specific gene from wheat, oxalate oxidase, into the American chestnut genome.[42] The enzyme oxalate oxidase is an extremely common fungal defense in plants, and is found in strawberries, bananas, oats, barley, and other cereals. Oxalate oxidase breaks down the oxalic acid which the fungus secretes in the cambium to lower the pH and subsequently kill plant tissues. The chestnut trees which contain this resistance gene can be infected by the chestnut blight, but the tree is not girdled by the resulting canker and heals around the wound. This lets the fungus fulfill its normal lifecycle without the death of the tree. The blight resistance gene is passed down to the tree's offspring to provide subsequent generations with partial blight resistance.[43] In 2015, the researchers are working towards applying for government permission to make these trees available to the public in the next five years.[44] These trees could be the first genetically modified forest trees released in the wild in the United States.[45][46]

Hypovirulence

Hypovirus is the only genus in the family Hypoviridae. Members of this genus infect fungal pathogens and reduce their ability to cause disease (hypovirulence).[47] In particular, the virus infects Cryphonectria parasitica, the fungus that causes chestnut blight, which has enabled infected trees to recover from the blight. The use of hypovirulence to control blight originated in Europe where the fungal virus spread naturally through populations of European chestnuts. The reduced ability of the fungus to cause disease allowed the European chestnut to regenerate, creating large stands of trees. Hypovirulence has also been found in North America, but has not spread effectively.[48] The "Arner Tree" of Southern Ontario, is one of the best examples of naturally occurring hypovirulence. It is a mature American chestnut that has recovered from severe infections of chestnut blight. The cankers have healed over and the tree continues to grow vigorously. Scientists have discovered that the chestnut blight remaining on the tree is hypovirulent, although isolates taken from the tree do not have the fungal viruses found in other isolates.[49] Trees inoculated with isolates taken from the Arner tree have shown moderate canker control.[50] The cankers of hypovirulent American Chestnut trees occurs on the outermost tissues of the tree but the cankers do not spread into the growth tissues of the American Chestnut tree, thereby providing it with a resistance[51]

Surviving specimens

- About 2,500 chestnut trees are growing on 60 acres near West Salem, Wisconsin, which is the world's largest remaining stand of American chestnut. These trees are the descendants of those planted by Martin Hicks, an early settler in the area, who planted fewer than a dozen trees in the late 1800s. Planted outside the natural range of chestnut, these trees escaped the initial onslaught of chestnut blight, but in 1987, scientists found blight in the stand. Scientists are working to try to save the trees.[52]

- Two of the largest surviving American chestnut trees are in Jackson County, Tennessee. One, the state champion, has a diameter of 61 cm (24 in) and a height of 23 m (75 ft), and the other tree is nearly as large. One of them has been pollinated with hybrid pollen by members of The American Chestnut Foundation; the progeny will have mostly American chestnut genes and some will be blight resistant.

- On May 18, 2006, a biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources spotted a stand of several trees near Warm Springs, Georgia. One of the trees is approximately 20–30 years old and 13 m (43 ft) tall and is the southernmost American chestnut tree known to be flowering and producing nuts.[53][54]

- Another large tree was found in Talladega National Forest, Alabama, in June 2005.[55]

- In the summer of 2007, a stand of trees was discovered near the northeastern Ohio town of Braceville.[56][57] The stand encompasses four large flowering trees, the largest of which is about 23 m (75 ft) tall, sited among hundreds of smaller trees that have not begun to flower, located in and around a sandstone quarry. A combination of factors may account for the survival of these relatively large trees, including low levels of blight susceptibility, hypovirulence, and good site conditions. In particular, some stands may have avoided exposure due to being located at a higher altitude than blighted trees in the neighboring area; the fungal spores are not carried to higher altitudes as easily.[56]

- In March 2008, officials of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources announced a rare adult American chestnut tree had been discovered in a marsh near Lake Erie. The officials admitted they had known about the tree for seven years, but had kept its existence a secret. The exact location of the tree is still being held secret, both because of the risk of infecting the tree and because an eagle has nested in its branches. They described the tree as being 89 feet (27 m) tall and having a circumference of 5 feet (1.5 m). The American Chestnut Foundation was also only recently told about the tree's existence.[58]

- Members of the Kentucky chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation have been pollinating a tree found on a farm in Adair County, and a specimen found on Henderson Ridge in Elliott County. The Adair County tree is over one hundred years old.[59][60]

- In June 2007, a mature American chestnut was discovered in Farmington, New Hampshire.[61]

- In rural Missaukee County, Michigan, a blight-free grove of American chestnut trees approximately 0.33 acres (0.13 ha) in size with the largest tree measuring 128 in (330 cm) in circumference (40 in (100 cm) diameter) has been located. It is believed to be the result of nuts planted by early settlers in the area. The American Chestnut Council, located in the local town of Cadillac, Michigan, has verified its identity and existence. Efforts have been initiated to protect the property from logging and development.

- In Lansing, Michigan, Fenner Nature Center is home to a grove of blight-free American chestnuts descended from the aforementioned grove in Missaukee County.[62]

- American chestnuts have been located on Beaver Island, a large island in northern Lake Michigan.[63]

- Hundreds of healthy American chestnuts have been found in the proposed Chestnut Ridge Wilderness Area in the Allegheny National Forest in northwestern Pennsylvania.[64] Many of these trees are large, measuring more than 60 ft (18 m) in height. These trees will be protected from logging if the wilderness area, proposed by Friends of Allegheny Wilderness, is passed into law.

- The Montreal Botanical Garden has the American chestnut among its collection of trees and ornamental shrubs.[65]

- Three of Portland, Oregon's heritage trees are American chestnuts, along with three Spanish (European) chestnuts.[66]

- At least two American chestnuts live on the side of Skitchewaug Trail in Springfield, Vermont.[67]

- Around 300 to 500 trees were spotted in the George Washington National Forest near Augusta County, Virginia, in 2014. Over one dozen trees were at least 12 inches in diameter with several measuring nearly 24 inches in diameter. Only one of the larger trees was a seed and pollen producer with numerous pods and pollen strands lying on ground. The site did, however, have a high presence of chestnut blight, although the seed producing tree and several other large ones were relatively blight-free with minimal to no damage.

- Two trees were planted 1985 in Nova Scotia, at Dalhousie University, Sexton Campus and are thriving. The donated trees were from saplings grown in Europe, away from the blight. They have 16" diameter trunks and are approximately 40 feet high.

- A single mature American chestnut can be found on the front lawn of the McPhail house heritage site in Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, planted by former mayor John Alexander McPhail in the 1920s. Well north of the natural range of the chestnut, it has avoided the blight.[68]

- There is one American chestnut in Pennsylvania in the county of Columbia in the township of South Centre. It is a hardy, nut producing tree that has been producing for nearly 30 years.

- A solitary tree exists in the New York County of Orange, within the Town of Wawayanda. This was planted in the early 1990s as part of a local soil and water conservation district program to identify blight/resistant specimens. It has borne fruit since 2005.

- A lone but "perfect" American Chestnut tree grows on the Oakdale Campus in Coralville, Iowa.[69]

- The great majority of chestnut trees in the United States are derived from Dunstan chestnuts, developed in Greensboro, N.C. in the 1960s.[70]

- The Canadian Chestnut Council has a plot growing and harvesting chestnut trees at Tim Hortons Children's Foundation Onondaga Farms. The seedlings are grown at a Simcoe, Ont, Canada station. They are then brought in the spring to this test plantation in St. George, Ont., between Brantford and Cambridge.[71]

Multiple chestnut trees still alive and nut bearing in Wind River Arboretum, Washington State.

Uses

Food and medicine

The nuts were once an important economic resource in North America, being sold on the streets of towns and cities, as they sometimes still are during the Christmas season (usually said to be "roasting on an open fire" because their smell is readily identifiable many blocks away). Chestnuts are edible raw or roasted, though typically preferred roasted. Nuts of the European sweet chestnut are now sold instead in many stores. One must peel the brown skin to access the yellowish-white edible portion. The unrelated horse-chestnut's seeds are poisonous without extensive preparation. Native Americans used various parts of the American chestnut to treat ailments such as whooping cough, heart conditions and chafed skin.[2] The nuts were commonly fed on by various types of wildlife and was also in such a high abundance that they were commonly used to feed livestock by farmers, by allowing those livestock to roam freely into the forests that were predominantly filled with American Chestnut trees.[20] The American Chestnut tree was also important to native Americans as it acted as a food source for both the native Americans and the Wildlife.[72]

Furniture and other wood products

The January 1888 issue of Orchard and Garden mentions the American chestnut as being "superior in quality to any found in Europe".[73] The wood is straight-grained, strong, and easy to saw and split, and it lacks the radial end grain found on most other hardwoods. The tree was particularly valuable commercially since it grew at a faster rate than oaks. Being rich in tannins, the wood was highly resistant to decay and therefore used for a variety of purposes, including furniture, split-rail fences, shingles, home construction, flooring, piers, plywood, paper pulp, and telephone poles. Tannins were also extracted from the bark for tanning leather.[2] Although larger trees are no longer available for milling, much chestnut wood has been reclaimed from historic barns to be refashioned into furniture and other items.[74]

"Wormy" chestnut refers to a defective grade of wood that has insect damage, having been sawn from long-dead, blight-killed trees. This "wormy" wood has since become fashionable for its rustic character.[74][75][76]

The American chestnut is not considered a particularly good patio shade tree because its droppings are prolific and a considerable nuisance. Catkins in the spring, spiny nut pods in the fall, and leaves in the early winter can all be a problem. These characteristics are more or less common to all shade trees, but perhaps not to the same degree as with the chestnut. The spiny seed pods are a particular nuisance when scattered over an area frequented by people.

See also

References

- Stritch, L. (2018). "Castanea Dentata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nixon, Kevin C. (1997). "Castanea dentata". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 3. New York and Oxford. Retrieved September 26, 2015 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Davis, Donald E. "Historical Significance of American Chestnut on Appalachian Culture and Ecology". www.ecosystem.psu.edu, 2005. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- Elliott, Katherine J.; Swank, Wayne T. (August 1, 2008). "Long-term changes in forest composition and diversity following early logging (1919–1923) and the decline of American chestnut (Castanea dentata)". Plant Ecology. 197 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1007/s11258-007-9352-3. ISSN 1573-5052.

- Griffin, Gary. "Recent advances in research and management of chestnut blight on American chestnut". Phytopathology 98:S7. www.apsnet.org, 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- Detwiler, Samuel. "The American Chestnut Tree: Identification and Characteristics". American Forestry 21.362 (October, 1915): 957-959. Washington D.C.:American Forestry Association, 1915. Google Books. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Hebard, F.V. "The American Chestnut Foundation Breeding Program". www.fs.fed.gov. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- Brewer, L. G. (1982). "The present status and future prospect for the American chestnut in Michigan". Michigan Botanist. 21: 117–128.

- Fulbright, D. W.; Weidlich, W. H.; Haufler, K. Z.; Thomas, C. S.; Paul, C. P. (December 1983). "Chestnut blight and recovering American chestnut trees in Michigan". Canadian Journal of Botany. 61 (12): 3164–3171. doi:10.1139/b83-354.

- "Species Profile (American Chestnut)". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Servies Endangered Species".

- Rea, Glen. "Blight Resistance" (PDF). Journal of American Chestnut Foundation.

- "Tree Breeding". The American Chestnut Foundation. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "American chestnut rescue will succeed, but slower than expected | Penn State University". news.psu.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Jackson, Teresa; Affairs, SRS Public. "Testing Blight Resistance in American Chestnuts". CompassLive. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Huang, Hongwen; Hawkins, Leigh K.; Dane, Fenny (November 1, 1999). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure of Castanea pumila var. ozarkensis". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 124 (6): 666–670. doi:10.21273/JASHS.124.6.666. ISSN 2327-9788.

- "A legendary Ozark chestnut tree, thought extinct, is rediscovered". Environment. June 24, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- Jabr, Ferris. "A New Generation of American Chestnut Trees May Redefine America's Forests". Scientific American, March 1, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- Merkel, Hermann W. "A Deadly Fungus on the American Chestnut". Annual Report of the New York Zoological Society, Volume 10 (1906). Charleston, SC:Nabu Press, 2011. ISBN 1245328581. Google Books. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "History of the American Chestnut". The American Chestnut Foundation. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Anagnostakis, Sandra. "Evolution of the Chestnut Tree and its Blight" (PDF).

- Dierauf, Tom (March 1997). "HIGH LEVEL OF CHESTNUT BLIGHT CONTROL ON GRAFTED AMERICAN CHESTNUT TREES INOCULATED WITH HYPOVIRULENT STRAINS". S2CID 83066643. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Mesic Southern Forest". www.mnfi.anr.msu.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- Garden, Missouri Botanical. "Chestnut Blight". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- "Cryphonectria_parasitica". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- "Bibliography." www.accf-online.org. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- Griffin, G.J., J.R. Elkins, D. McCurdy, and S. L. Griffin. "Integrated use of resistance, hypovirulence, and forest management to control blight on American chestnut." www.ecosystems.psu.edu, 2005.

- "Restoration of American Chestnut to Forest Lands: Proceedings of a Conference and Workshop Held May 4-6, 2004 at The North Carolina Arboretum." www.archive.org. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "Breeding for Blight Resistance." www.accf-online.org. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- "American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation 2015 Newsletter: Grower Reports." www.accf-online.org. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- "Conservation - Genetic Research" Archived April 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. www.charliechestnut.org. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- Galloway, Paul R. "My Chestnut Story" Archived October 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. www.acf.org. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- Burnham, Charles R (1986). "Chestnut Hybrids from the USDA-Connecticut Breeding Programs". The Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation. 1 (2): 8–13.

- Valigra, Lori. "Back-Breeding Could Restore Chestnut Trees Ravaged by Blight". National Geographic News, December 29, 2005. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- "Planting and growing chestnut trees" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. www.acf.org. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- Barnes, Philip. "Return of the Native: Biologists revive the chestnut tree at former coal mine sites". www.ohio.edu. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- "Trying to Light A Fire Under Chestnut Revival". The Washington Post. December 29, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- "American Chestnut Restoration Breakthrough: The Tale of a Tree". Wayback Machine. www.greenxc.com, June 28, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- "Nut Grower's Guide--Chestnut: American Chestnut" Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Northern Nut Growers Association, Inc. www.nutgrowing.org. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- Burnham, Charles R. (1988). "The Restoration of the American Chestnut: Mendelian genetics may solve a problem that has resisted other approaches". American Scientist. 76 (5): 478–487. ISSN 0003-0996. JSTOR 27855387.

- Zhang, Bo; Oakes, Allison D.; Newhouse, Andrew E.; Baier, Kathleen M.; Maynard, Charles A.; Powell, William A. (March 31, 2013). "A threshold level of oxalate oxidase transgene expression reduces Cryphonectria parasitica-induced necrosis in a transgenic American chestnut (Castanea dentata) leaf bioassay". Transgenic Research. 22 (5): 973–982. doi:10.1007/s11248-013-9708-5. PMC 3781299. PMID 23543108.

- "Blight-resistant American chestnut trees take root at SUNY-ESF". www.phys.org, November 6, 2014. Retrieved September 23, 0214.

- Newhouse, Andrew E.; Polin-McGuigan, Linda D.; Baier, Kathleen A.; Valletta, Kristia E.R.; Rottmann, William H.; Tschaplinski, Timothy J.; Maynard, Charles A.; Powell, William A. (November 2014). "Transgenic American chestnuts show enhanced blight resistance and transmit the trait to T1 progeny". Plant Science. 228: 88–97. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.04.004. PMID 25438789.

- Jabr, Ferris. "A New Generation of American Chestnut Trees May Redefine America's Forests". Scientific American 310.3 (March 1, 2014). Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- Thompson, Helen (2012). "Plant science: The chestnut resurrection". Nature. 490 (748): 22–23. Bibcode:2012Natur.490...22T. doi:10.1038/490022a. PMID 23038446.

- Wines, Michael (July 13, 2013). "Like-Minded Rivals Race to Bring Back an American Icon". New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "Notes on Genus: Hypovirus". www.dpvweb.net. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Frequently Asked Questions" Archived October 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. www.acf.org. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- "Hypovirulence". www.canadianchestnutcouncil.ca. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "NE-140 Technical Committee Meeting Biological Improvement of Chestnut(Castanea spp.)and Management of Pests". www.ecosystem.psu.edu, October 20, 2001. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- Griffin, Gary (February 2000). "Blight Control and Restoration of the American Chestnut". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Childs, Gina. "Chestnut's Last Stand". Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine, August 2002. www.dnr.wi.gov. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- Minor, Elliott. "Rare American Chestnut Trees Discovered". The Washington Post, May 19, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Merkle, Scott A. "American Chestnut". New Georgia Encyclopedia, February 11, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Spencer, Thomas. "Seeds of hope arise for American Chestnuts, head of Alabama chapter of American Chestnut Foundation says". The Birmingham News, December 4, 2010. www.blog.al.com. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Stand of Chestnut Trees Defying Odds". The Bryan Times, August 27, 2007. Google News. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Haddon, Heather. "Hopes for a Chestnut Revival Growing". The Wall Street Journal, August 19, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- "Rare American chestnut tree discovered in Sandusky marsh". Akron Beacon Journal, June 17, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "State's largest historic Chestnut tree stands on an Adair County farm". www.columbiamagazine.com, June 17, 2005. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- Flavell, John. "American tale: Bringing back the perfect tree". www.dailyindependent.com, July 24, 2009.

- Ramsdell, Laurenne. "Farmington chestnut tree may have saved species". www.fosters.com, July 21, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- Hull, Christopher. "The American Chestnut Project at Fenner Nature Center" Archived May 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. www.mynaturecenter.org. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- Whately, Cathryn Elizabeth, Daniel E. Wujek and Edwin E. Leuck II. "The Vascular Flora of Hog Island, Charlevoix County, Michigan". The Michigan Botanist 44.1 (Winter, 2005): 29-48. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- Friends of Allegheny Wilderness. "A Citizens’ Wilderness Proposal for Pennsylvania’s Allegheny National Forest". Friends of Allegheny Wilderness, 2003. www.pawild.org. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Trees and Ornamental Shrubs: American chestnut [English page]". Montreal Botanical Garden. Space for Life Montreal. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Castanea dentata". Portland Parks and Recreation. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- Smallheer, Susan. "Couple works to save ailing American chestnut tree" Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Rutland Herald, July 18, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- Della-Mattia, Elaine (April 5, 2011). "McPhail house registered as heritage home". Sault Star. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- . "Iowa now, Tree Freak" Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Dunstan chestnut trees" Archived April 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. www.chestnuthilltreefarm.com. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- "Canadian Chestnut Council".

- Schlarbaum, Scott (1998). "THREE AMERICAN TRAGEDIES: CHESTNUT BLIGHT, BUTTERNUT CANKER, AND DUTCH ELM DISEASE" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fuller, A. S. "Nuts & Nut Trees". Orchard and Garden, 10 (January 1888): 5. Little Silver, NJ: J.T. Lovett. via Google Books. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "The American Chestnut Foundation Chair". Archived October 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine www.tappanchairs.com. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "Wormy Chestnut". www.wood-database.com. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- " Antique Wormy Chestnut Lumber". www.appalachianwoods.com. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castanea dentata. |

- American Chestnut Habitat

- Flora of North America

- RangeMap: American chestnut

- The American Chestnut Foundation

- American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation

- Canadian Chestnut Council

- American Chestnut Research and Restoration Center, SUNY-ESF

- Castanea dentata images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- http://www.ohenrymag.com/the-nutty-professor/