Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922) was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror, he was an early developer of popular journalism, and he exercised vast influence over British popular opinion during the Edwardian era. Lord Beaverbrook said he was "the greatest figure who ever strode down Fleet Street."[1] About the beginning of the 20th century there were increasing attempts to develop popular journalism intended for the working class and tending to emphasize sensational topics. Harmsworth was the main innovator.

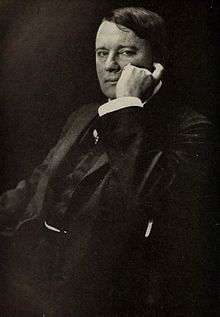

The Viscount Northcliffe | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, by Gertrude Kasebier | |

| Born | Alfred Charles William Harmsworth 15 July 1865 Chapelizod, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 14 August 1922 (aged 57) Carlton House Gardens, London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Stamford School, Stamford, Lincolnshire, England |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Title | 1st Viscount Northcliffe |

| Parent(s) | Alfred Harmsworth & Geraldine Mary Maffett |

| Relatives | Cecil Harmsworth (brother) Harold Harmsworth (brother) Leicester Harmsworth (brother) Hildebrand Harmsworth (brother) |

Northcliffe had a powerful role during the First World War, especially by criticizing the government regarding the Shell Crisis of 1915. He directed a mission to the new ally, the United States, during 1917, and was director of enemy propaganda during 1918.

His Amalgamated Press employed writers such as Arthur Mee and John Hammerton, and its subsidiary, the Educational Book Company, published The Harmsworth Self-Educator, The Children's Encyclopædia, and Harmsworth's Universal Encyclopaedia.

Biography

Early life and success

Born in Chapelizod, County Dublin, the son of Alfred and Geraldine Harmsworth, he was educated at Stamford School in Lincolnshire, England, from 1876 and at Henley House School in Kilburn, London from 1878.[2] A master at Henley House who was to prove important to his future was J. V. Milne, the father of A. A. Milne, who according to H. G. Wells was at school with him at the time and encouraged him to start the school magazine.[3] In 1880 he first visited the Sylvan Debating Club, founded by his father, and of which he later served as Treasurer.

Beginning as a freelance journalist, he initiated his first newspaper, Answers (original title: Answers to Correspondents), and was later assisted by his brother Harold, who was adept in business matters. Harmsworth had an intuitive sense for what the reading public wanted to buy, and began a series of cheap but successful periodicals, such as Comic Cuts (tagline: "Amusing without being Vulgar") and the journal Forget-Me-Not for women. From these periodicals, he developed the largest periodical publishing company in the world, Amalgamated Press.[4] His half-penny periodicals published in the 1890s played a role in the decline of the Victorian penny dreadfuls.[5]

Harmsworth was an early developer of popular journalism. He bought several failing newspapers and made them into an enormously profitable news group, primarily by appealing to the general public. He began with The Evening News during 1894, and then merged two Edinburgh papers to form the Edinburgh Daily Record. That same year he funded an expedition to Franz Joseph Land in the Arctic with the intention of making attempts to travel to the North Pole.[6]

On 4 May 1896 he began publishing the Daily Mail in London, which was a success, having the world record for daily circulation until Harmsworth's death; taglines of the Daily Mail included "the busy man's daily journal" and "the penny newspaper for one halfpenny". Prime Minister Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury, said it was "written by office boys for office boys".[7] Harmsworth then transformed a Sunday newspaper, the Weekly Dispatch, into the Sunday Dispatch, then the greatest circulation Sunday newspaper in Britain. He also initiated the Harmsworth Magazine (later London Magazine 1898–1915), utilizing one of Britain's best editors, Beckles Willson, who had been editor of many successful publications, including The Graphic.[8]

During 1899 Harmsworth was responsible for the unprecedented success of a charitable appeal for the dependents of soldiers fighting in the South African War by inviting Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Sullivan to write the song "The Absent-Minded Beggar".[9]

Harmsworth also initiated The Daily Mirror during 1903, and rescued the financially desperate Observer and The Times during 1905 and 1908, respectively.[10] During 1908, he also acquired The Sunday Times. The Amalgamated Press subsidiary the Educational Book Company published the Harmsworth Self-Educator, The Children's Encyclopædia, and Harmsworth's Universal Encyclopaedia.[11] He brought his younger brothers into his media empire, and they all flourished: Harold Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere, Cecil Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth, Sir Leicester Harmsworth, 1st Baronet and Sir Hildebrand Harmsworth, 1st Baronet.

Ennobled

Harmsworth was created a Baronet, of Elmwood, in the parish of St Peters in the County of Kent during 1904.[12] During 1905, Harmsworth was named to the peerage as Baron Northcliffe, of the Isle of Thanet in the County of Kent,[13] and during 1918 was named as Viscount Northcliffe, of St Peter's in the County of Kent, for his service as the director of the British war mission in the United States.[14]

Marriage

Alfred Harmsworth married Mary Elizabeth Milner on 11 April 1888. She was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) and Dame of Grace, Order of St John (D.St.J) during 1918. They did not have any children.[15]

Children

Alfred Harmsworth had four acknowledged children by two different women. The first, Alfred Benjamin Smith, was born when Harmsworth was seventeen years old; the mother was a sixteen-year-old maidservant in his parents' home.[16] Smith died during 1930, allegedly in a mental home.[17] By 1900, Harmsworth had acquired a new mistress, an Irishwoman named Kathleen Wrohan, about whom little is known but her name; she bore him two further sons and a daughter, and died during 1923.[18]

Political influence

By 1914 Northcliffe controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation.[19]

_(14595849278).jpg)

Northcliffe's ownership of The Times, the Daily Mail and other newspapers meant that his editorials influenced both "the classes and the masses".[20] In an era before radio, television or internet, that meant that Northcliffe dominated the British press "as it never has been before or since by one man".[21]

Northcliffe's editorship of the Daily Mail in the years just preceding the First World War, when the newspaper displayed "a virulent anti-German sentiment", caused The Star to declare, "Next to the Kaiser, Lord Northcliffe has done more than any living man to bring about the war."[22] His newspapers—especially The Times—reported the Shell Crisis of 1915 with such zeal that it helped to end the Liberal government of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, forcing Asquith to form a coalition government (the other causal event was the resignation of Admiral Fisher as First Sea Lord). Lord Northcliffe's newspapers propagandized for creating a Minister of Munitions (a job first held by David Lloyd George) and helped to bring about Lloyd George's appointment as prime minister during 1916. Lloyd George offered Lord Northcliffe a job in his cabinet, but Northcliffe refused and was appointed director for propaganda.[23]

Such was Northcliffe's influence on anti-German propaganda during the First World War that a German warship was sent to shell his house, Elmwood, in Broadstairs,[24] in an attempt to assassinate him.[25] His former residence still bears a shell hole out of respect for his gardener's wife, who was killed in the attack. On 6 April 1919, Lloyd George made an excoriating attack on Harmsworth, terming his arrogance "diseased vanity". By that time Harmsworth's influence was decreasing.

Northcliffe's enemies accused him of power without responsibility, but his papers were a factor in settling the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921, and his mission to the United States at the start of the Great War has been judged a success by the historians.[26]

Northcliffe's personality shaped his career. He was monolingual and not well-educated; he knew little history or science. He had a lust for power and for money, while leaving the accounting paperwork to his brother Harold. He imagined himself Napoleon reborn, and did resemble the emperor physically and in terms of enormous energy and ambition. Above all, he had a boyish enthusiasm for everything. Norman Fyfe, an intimate friend, states he was:

Boyish in his power of concentration upon the matter of the moment, boyish in his readiness to turn swiftly to a different matter and concentrate on that. . . . Boyish the limited range of his intellect, which seldom concerns itself with anything but the immediate, the obvious, the popular. Boyish his irresponsibility, his disinclination to take himself or his publications seriously; his conviction that whatever benefits them is justifiable, and that it is not his business to consider the effect of their contents on the public mind.[27]

Sport

In 1903 Harmsworth initiated the Harmsworth Cup, the first international award for motorboat racing.[28]

Motoring

Harmsworth was a friend of Claude Johnson, chief executive of Rolls-Royce Limited, and during the years preceding the First World war became an enthusiast of the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost car.[29]

Death

Alfred Harmsworth's health declined during 1921 due mainly to a streptococcal infection. He went on a world tour to revive himself, but it failed to do so. He died of endocarditis in a hut on the roof of his London house, No. 1 Carlton House Gardens, during August, 1922,[30] and left three months' pay to each of his six thousand employees. The viscountcy, barony, and baronetcy of Northcliffe became extinct.

A monument to Northcliffe at St Dunstan-in-the-West, Fleet Street, London, was unveiled in 1930. The obelisk was designed by Edwin Lutyens and the bronze bust is by Kathleen Scott. His body was buried at East Finchley Cemetery in North London.[31]

Legacy

Historian Ian Christopher Fletcher states:

Northcliffe's drive for success and respectability bounded main outlet in the commercial world of journalism, not the political world the parties and parliaments. Perhaps his greatest accomplishment, underlying the relentless acquisition of newspapers and perfection of their "copy," was the simple incorporation of millions of readers into his press empire.[32]

A. J. P. Taylor, however, says, "Northcliffe could destroy when he used the news properly. He could not step into the vacant place. He aspired to power instead of influence, and as a result forfeited both."[33]

P. P. Catterall and Colin Seymour-Ure conclude that:

More than anyone [he] ... shaped the modern press. Developments he introduced or harnessed remain central: broad contents, exploitation of advertising revenue to subsidize prices, aggressive marketing, subordinate regional markets, independence from party control.[34]

The A. Harmsworth Glacier in North Greenland was named by Robert Peary in his honour. Harmsworth had gifted Peary expedition ship "Windward" following a lecture on Polar exploration he gave at the Royal Geographical Society in 1897.[35]

Promotion of Group Settlement Scheme

Through his newspaper career, Northcliffe promoted the ideas which resulted in the Group Settlement Scheme. The scheme promised land in Western Australia to British settlers prepared to emigrate and develop the land. A town founded specifically to assist the new settlements was named Northcliffe, in recognition of Lord Northcliffe's promotion of the scheme.

Northcliffe lived for a time at 31 Pandora Road, West Hampstead – this site is now marked with an English Heritage blue plaque.

See also

References

- Lord Beaverbrook, Politicians and the War, 1914–1916 (1928) 1:93.

- "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- H. G. Wells, An Experiment in Autobiography, Chapter 6

- Boyce (2004).

- Springhall, John (1998). Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-312-21394-7. OCLC 38206817.

- Brice, Arthur Montefiore, and H. Fisher. "The Jackson-Harmsworth Polar Expedition, Notes of the Last Year's Work." The Geographical Journal 8.6 (1896): 543–564. online

- Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, 1975

- "Victorian Secrets". History of Harmsworth Magazine. victoriansecrets.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Cannon, John. "The Absent-Minded Beggar", Gilbert and Sullivan News, March 1987, Vol. 11, No. 8, pp. 16–17, The Gilbert and Sullivan Society, London.

- "Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Viscount Northcliffe | British publisher". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Boyce (2004).

- "No. 27696". The London Gazette. 15 July 1904. p. 4556.

- "No. 27871". The London Gazette. 5 January 1906. p. 107.

- "No. 30533". The London Gazette. 19 February 1918. p. 2212.

- Taylor, S. J. (1996). The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 47. ISBN 978-0297816539.

- Taylor The Great Outsiders pp.10–11

- Taylor The Great Outsiders p. 222

- Taylor The Great Outsiders pp. 47–48 and p. 222.

- Tompson, "Fleet Street Colossus" p. 115.

- Blake, Robert (1955). The Unknown Prime Minister: The Life & Times of Andrew Bonar Law 1858–1918. p. 294.

- Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace. p. 233.

- Bingham, Adrian (May 2005). "Monitoring the popular press: an historical perspective". History & Policy. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- Boyce (2004).

- 51.3739°N 1.4337°E

- "Kent Today & Yesterday". 1 January 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- John Cannon, ed., The Oxford Companion to British History (2002) p. 454.

- Hamilton Fyfe, Northcliffe an Intimate Biography (1930) p. 106.

- "Harmsworth Cup | motorboat racing award". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Pugh, Peter (2001). The Magic of a Name The Rolls-Royce Story: The First 40 Years. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-151-0.

- Wilson, A. N. (2005). "12: Chief". After the Victorians. Hutchinson. pp. 191–2. ISBN 978-0-09-179484-2. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "Alfred Harmsworth – Find a Grave". findagrave.com. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Ian Christopher Fletcher , "Northcliffe, Lord" in Fred M. Leventhal, ed., Twentieth-century Britain: an encyclopedia (Garland, 1995) pp 573–74

- A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914-1945 (1965) p 27.

- P. P. Catterall and Colin Seymour-Ure, "Northcliffe, Viscount". in John Ramsden, ed. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics (2002) p. 475.

- Daniel E. Harmon, Robert Peary. 2013

Further reading

- Boyce, D. George (2004). Harmsworth, Alfred Charles William, Viscount Northcliffe (1865–1922). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press.

- Chalaby, Jean K. "‘Smiling Pictures Make People Smile’: Northcliffe's journalism." Media History 6.1 (2000): 33-44.

- Koss, Stephen. The rise and fall of the political press in Britain Vol. 2: the Twentieth Century (1984).

- Pound, Reginald, and Geoffrey Harmsworth. Northcliffe (Cassell, 1959).

- Sullivan, March (September 1922). "Northcliffe: Living, Dying, Dead". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV: 648–654. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- Taylor, S.J. The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere, and the Daily Mail (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1996).

- Thompson, J. Lee. Press Barons in Politics 1865–1922 (London, 1996).

- Thompson, J. Lee. "Fleet Street Colossus: The Rise and Fall of Northcliffe, 1896-1922." Parliamentary History 25.1 (2006): 115–138. online

- Thompson, J. Lee. "‘To Tell the People of America the Truth’: Lord Northcliffe in the US, Unofficial British Propaganda, June–November 1917." Journal of Contemporary History 34.2 (1999): 243–262.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe. |

- "DMGT, Rothermere and Northcliffe" at Ketupa.net Media Profiles 2006-12-11

- Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe at Spartacus-Educational.com

- Who's Who: Lord Northcliffe

- Europeana Collections 1914–1918 makes 425,000 First World War items from European libraries available online, including relevant volumes of The Northcliffe Papers

- Newspaper clippings about Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Alfred Harmsworth, Viscount Northcliffe at Library of Congress Authorities, with 9 catalogue records