A Crow Looked at Me

A Crow Looked at Me is the eighth studio album by Mount Eerie, a solo project by American musician Phil Elverum. It was released on March 24, 2017, on Elverum's own label, P.W. Elverum & Sun. It is a concept album about the death of Elverum's wife, the Canadian cartoonist and musician Geneviève Castrée. The album was written and produced entirely by Elverum, who recorded it, using mostly Castrée's instruments and notes he had compiled about Castrée, in the room in which she died. A departure from Elverum's previous work, A Crow Looked at Me features minimal production and sparse instrumentation with lyrics that tell of Castrée's illness and death, his ensuing grief, his relationship to nature after her death and their recently born child.

| A Crow Looked at Me | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | March 24, 2017 | |||

| Recorded | August 31 – December 6, 2016 | |||

| Studio | Home recording, Anacortes, Washington | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 41:30 | |||

| Label | P.W. Elverum & Sun | |||

| Producer | Phil Elverum | |||

| Mount Eerie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Mount Eerie studio album chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from A Crow Looked at Me | ||||

| ||||

To promote the album Elverum released two singles, "Real Death" on January 18, 2017, and "Ravens" on February 15, 2017 and embarked on North American/European tours. A select show was recorded and released as the 2018 live album (after). A Crow Looked at Me was an immediate and widespread critical success, appearing on numerous year-end lists. In the years following its release, the album has appeared on multiple decade-end lists. Some critics found because of the album's personal nature, reviewing was difficult and felt disrespectful. Elverum's subsequent albums Now Only (2018) and Lost Wisdom Pt. 2 (2019) serve as continuations, with Castrée's illness and death being central to both.

Background and composition

.jpg)

In 2015, four months after the birth of their first child, Phil Elverum's wife, Canadian cartoonist and musician Geneviève Castrée, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She died at their home in Anacortes, Washington, on July 9, 2016.[1][2] Taking inspiration from the Gary Snyder poem "Go Now",[3] Elverum realised that he did not have to find meaning in Castrée's death but could write songs that described the experience.[4] He found inspiration in the work of Canadian singer-songwriter Julie Doiron, American poet Joanne Kyger, American rock band Sun Kil Moon, Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgård and American singer-songwriter Will Oldham whose 1996 album Arise Therefore influenced the album's sound, in particular its sparse production.[5][6][7][8] Elverum felt compelled to make the album as he found that the art he treasured was ineffective in helping him cope. He confided to Donovan Burtan of Cult MTL that "all the things that used to bring me a sense of meaning and depth and comfort, all these books in the house of poetry, philosophy and everything — all of it was just empty and useless".[9]

After Castree's death, Elverum considered retiring from music and becoming a full-time father, but a trip to Haida Gwaii inspired him to write notes, along with those he had written during Castrée's illness and treatment, which would become the album.[11][12] Elverum recorded the album between August 31 and December 6, 2016, at his house in Anacortes, Washington.[2][13] He wrote the songs over a six-week period[8] beginning in September 2016.[11] He wrote the lyrics longhand on Castrée's notepaper,[14] and recorded the songs in the room where she died. He had previously abandoned the room, opened its window and allowed nature to take it over.[15] Elverum credits recording in her room as the reason behind the album's "immediacy" and "bluntness".[16] He originally intended to record the album with a live band in a studio. He found that the songs were too personal to have others contribute to them, however, so he opted to play them himself.[8] Elverum used an acoustic guitar, one microphone and a laptop computer[11] along with some of Castrée's own instruments.[17] Since he had become the primary carer for his daughter, Elverum recorded the songs at night while his daughter was asleep[lower-alpha 1] or during times when she was visiting friends.[11] He described his process as writing down the songs first on paper. He then practiced them rigorously until the point when he knew where each chord was in sequence—a first for him.[19] In an interview Elverum talked about how he would choose to record over self care saying he could either shower or write down ideas "bursting" in his head.[20]

The best thing about the past

is that it's over

when you die.

you wake up

from the dream

that's your life.

Then you grow up

and get to be post human

in a past that keeps happening

ahead of you

Joanne Kyger

Elverum said that the songs "poured out quickly in the fall, watching the days grey over and watching the neighbors across the alley tear down and rebuild their house", with him filling the pages of his notebook with a "formless, no-rhythm, no-meter, no-melody blob of words".[21][22] He made and released the record to make the intensity of his love for his wife "known" and to draw a distinction between "art and music" and the "experience of life".[9][22] While he wrote the album, Elverum intended that the songs have a "hyper-intimate" and unrestrained quality. He wanted them to be philosophical[23] but devoid of symbolism and distinct from the more existential themes of his earlier work.[24][25] Elverum said he had no goal in mind while creating the album just that he was in an "unpremeditated way going with the flow".[9] He has also said that he does not view the album as a tribute to, or being about, Castrée. He believed if he were to make a tribute it would be ineffective in capturing who Castrée was. He viewed the album instead as detached from Castrée and a documentation of his grief, "saying all the heavy stuff with no regard for other people's sensitivity or unwillingness".[9][18][21] Elverum found the album's overall creation positive, saying it was "therapeutic" and felt as if he was "hanging out" with Castrée, feeling by the end as if he had healed.[19][26]

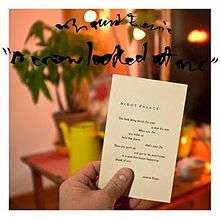

The album cover features a photograph of the poem "Night Palace" by Castrée's close friend Joanne Kyger.[lower-alpha 2] Castrée had pinned above her desk.[23] When he was cleaning out her room after she died Elverum realised the poem encapsulated the album's theme. Castrée's copy of Hergé's Tintin in Tibet can be seen in the background.[8]

Music and lyrics

The lyrics are delivered in a speaking and singing manner.[28] They deal with Castrée's illness and death,[29] Elverum's ensuing grief,[30] and the idea there is nothing to learn or gain from death.[31] Alongside the central theme of Castrée's illness and death. Themes of impermanence,[11] emptiness,[29] and disorientation[32] are present in the album as well. Many of the lyrics feature references to nature[29] with one reviewer noting that "tragedy hasn't stopped [Elverum] from noticing the world; if anything, it seems to have pried his eyes open for good."[33] The lyrics also feature references to his past work. He intended the album to "correct" his previous works in which he was "exploring the idea of death without really having a sense of the human experience of it".[25] In a press release for the album, Elverum described the songs as being about:

The brutal details of that experience,[Castrée's illness and death], from the hospitalizations to the grieving, the specific domestic banalities that become existential in the context of such huge and abrupt loss. These songs are not fun. They are pretty and they are deep, and they find a love that prevails beneath the overwhelming and real sorrow. It is unlike anything else in the Mount Eerie catalog in its unvarnished expressions of personal grief, metaphor-free.[34]

The words take the form of a diary. Elverum intended that each song reflect a time in his grieving and include references to specific events and dates. He said that "each song is anchored to a very specific moment".[10] Thomas Britt wrote that this showcases "the way that death hangs over each day that follows".[29] Each song refers to Castrée—sometimes directly by name. Elverum frequently uses pronouns such as "our" when referring to Castrée despite her absence. One critic noted that this is because Elverum "struggles to adjust to the undesired change".[14][35] The final song "Crow" is, however, addressed prominently to their daughter.[30]

Elverum's vocals were described by Tomas Guarna as "weak and shy" showing him "completely consumed by a cruel, unforgiving world".[36] The album's lyrics have been described as combining "emotional intimacy and tonal frankness to a degree rarely heard in contemporary music" and as "unspooling pieces of prose"[37][38] The songwriting has been described as "brilliant examples of breaking the fourth wall" though the term itself does not align with the style of the material. It is "too precise" because the lines are blurred "between singing, speaking and raw emotional data dump."[30][39]

Musically, the album is reminiscent of his 2008 albums Dawn and Lost Wisdom[2][40] with the songs featuring sparse instrumentation—acoustic guitar, chord changes,[41] simple 4/4 percussion, piano,[42] no choruses and "barely any melodies".[43][44] This reflects Elverum's wish to move away from his earlier, more "artistically challenging" work, which was characterised by "harsh tones" and "complicated chords".[21] Jayson Greene of Pitchfork wrote that the "difference between this album and everything else he’s done is the difference between charting a voyage around the earth and undertaking it."[11] The sparse nature of the album led Elverum to refer to it as "barely music".[33] The songs include unresolved notes and chords such as the ending of "Seaweed" which hangs on a half-step descent, major chord.[45][41] The album is less musically dark to the rest of the Mount Eerie discography.[31] Elverum wanted to release the album quickly, so he used minimal production.[46] This was his first album to be produced entirely on a computer.[47]

The opening track "Real Death" features spoken-word vocals which are "whispered from a void of hurt" with a piano, electric guitar and drum accompaniment.[48][49][50] The song describes the "impossibility of representing loss" and "the hopelessness" after death.[36][51] It features the opening lyrics, "death is real"; the theme and the phrase continue throughout the record.[30][52][53] The song also introduces the theme that the album is not an artistic statement. With the lyrics, "it's [death] not for singing about/It's not for making into art", Elverum clarifies that although the album is art, the line is about "the difference between the idea of a thing and the actual lived experience of it".[50] Phillip Green of Cisternyard Media speculated that in saying this, Elverum did not want to take "advantage of Castrée's passing".[35] The song also refers to him opening packages addressed to Castrée delivered after her death; what one critic called a moment that "limns the space between the living and the dead"[30] It opens with a major chord.[54]

Elverum discusses scattering Castrée's ashes, the house they intended to build in Haida Gwaii and the fear of forgetting of the small details of Castrée's life such as her favourite flowers on "Seaweed".[48][55][56] Elverum revealed in an interview that the first version of the song was created on a hike with his daughter and he recorded the bare bones of the song into his phone.[19] The song is composed of "warm" guitar plucking, "discordant" piano and "hollowed" bass.[49] It also introduces the themes of Castrée's "Spiritual omnipresence", Castree "surviving" through their daughter and Elverum remembering her beyond the physical, choosing to immortalize her as the sunset, instead of as ashes.[lower-alpha 3][35][53][57] Writer Molly Beauchemin wrote that the song "stands apart for its crushing invocation of nature as a place of solace and refuge – a place to see purpose in the midst of loss".[58]

"Ravens" describes Elverum giving away Castrée's clothes. It details from her final days when he was splitting wood and witnessed two "big black birds", understanding them to be an omen but unclear of what.[30][48][59] Elverum expressed in an interview regret over having to repeatedly describe and sing Castrée's final days.[60] The song was inspired by Elverum's trip to Hadai Gwaii, his illness during the trip and the presence of ravens throughout the area.[61] "Ravens" and "Soria Moria" stand apart from the other songs in that they feature multiple tempo changes.[49] "Ravens" has been described as the centrepiece of the album with its "hushed acoustic guitar, ominous piano notes, and stark reminders of Geneviève's absence".[62] Sam Sodomsky of Pitchfork called the song a "seven-minute exploration of the horrors of this world".[63]

The track "Forest Fire" describes Elverum's feelings about death, decay, and absurdity in relation to the world around him.[64] He apologizes to Castrée for attempting to move on, for going through her things and wondering how he will live without her.[31][36][65] The fire represents a sort of "cleansing", although of what is unclear.[17] Nitsuh Abebe of The New York Times described the song as a "perfectly accurate description of our actual world".[64] "Swims" details Elverum's experiences with grief counselling and the sudden death of his counsellor.[40] It was described by one reviewer as "one of the most heart wrenching songs created".[66] It features minimal guitars, simple piano chords, bass guitar, "lo-fi soundscapes" and what has been described as "Elverum's most naked vocal performance".[49][40]

"My Chasm" demonstrates Elverum's difficulty in talking about his loss in public and has been described as "a tribute to [the couple's] everlasting love".[22][30] It features electronic instrumentation with piano accompaniment.[49] Elverum's vocal performance was described as having "identifiable pain" which is almost palpable.[49] "When I Take the Garbage Out At Night" invokes mundane imagery with one writer drawing comparisons to Sun Kil Moon's Benji.[28]

"Emptiness pt. 2" deals with the idea of "conceptual emptiness" with Elverum comparing his grief to "climbing up a mountain in complete loneliness".[36][2] The phrase "conceptual emptiness" is a reference to his song entitled "Emptiness" from his 2015 album Sauna.[39] At one point in the song Elverum sings the lyrics "Your absence is a scream". The word scream is deliberately drawn out. Jayson Greene compared listening to this moment to "pressing your hand against ice and leaving it there."[11] Thomas Britt of PopMatters wrote that the song's "self-reflexive commentary reframes even the most powerful pictures of wind-hewn, frosted, blackened solitude in the past Microphones/Mount Eerie songbook as products of comparative comfort; luxuries of imagination".[29]

Elverum discusses the fading familiar memories of Castrée in the song "Toothbrush/Trash" which has been described as a "horrible realization that time will not relent".[30] Conversely the song has been described as the "most uplifting track" on the album which conveys "the paradoxically happy and miserable state of acceptance".[67] Its sudden sound cue of a door closing, recorded by Elverum, was described by Brian Roesler as "a haunted chamber of memory and connection that now seems more real than ever".[49]

The track "Soria Moria" takes its name from the eponymous painting by Theodor Kittelsen, incorporates elements of black metal[53] and details Elverum's relationship with Castrée before her death. It also references his time in a Norwegian cabin where he wrote his 2008 album Dawn and interpolates the lyric, "I went back to feel alone there" from his 2001 song "The Moon".[52][68] The song's lyrics "[associate] a foggy, impassable distance with the taut sense of limbo associated with plain-facedly dealing with hospital chores".[57] "Soria Moria" is the only song on the album to have anything that resembles a refrain.[40] Musically the song is reminsent of his 2009 album Wind's Poem.[40] Thomas Britt of PopMatters described the song and its use of natural imagery as "one of the most vivid illustrations of Walter Benjamin's concept of 'aura' that I've ever encountered".[29][lower-alpha 4] A live version of the song was used as the lead single for his 2018 live album (after).[70]

The final song "Crow" is addressed to his daughter. Elverum details a hiking trip in the Pacific Northwest where a crow was following them.[30][19] "Crow" was the final song to be written and was not going to be included on the album. Elverum decided to include the song to reflect the events of the world at the time. It is the only song that refers to events beyond Elverum's life. He describes the world as "[s]moldering and fascist", comments inspired by the 2016 United States presidential election.[19] The titular crow is used in the song as a symbol of death's encompassing grasp.[66] The song has been described as an epilogue which "offers a new and hopeful perspective" and "one of the more poetic tracks on the album".[30][35]

Release and promotion

Elverum had considered not releasing the album at all, or changing his band's name entirely but did neither.[10] He had planned originally for a small-scale release of the record on his website, but as the album took shape he felt that it was good and wanted it to reach a wider audience.[71] He found releasing the album and promoting it to be "gross and weird from a lot of perspectives".[10] On January 6, 2017, he announced that he would go on tour and release a new album.[72] The next day, he played his first concert since September 2014 at a record store in Anacortes, Washington, called The Business.[73] The concert lasted 45 minutes and he played the album in its entierty.[74] He had to ask fans to stay away because the response was "overwhelming" and the store held only 50 people.[75] Elverum performed the show with his eyes closed in the corner of the room, leaving immediately afterwards.[73][76] The show was noticeably sparse, featuring no mic or amplification with Elverum using only his acoustic guitar.[73] Music critic Eric Grandy described the show as "heavy and awkward and weird" but also that it "felt supportive and cathartic and necessary" noting the crowd's emotional reaction.[73]

The first song to be released was "Crow" on a charity album entitled "Is There Another Language?" on January 20, 2017.[77] The first single from A Crow Looked at Me, "Real Death", was released on P.W. Elverum & Sun, Ltd.'s SoundCloud page on January 25, 2017,[5] to widespread acclaim, netting the "Best New Track" distinction from Pitchfork[78] and appearing on The Fader's list of "13 Songs You Need In Your Life This Week"[79] and Stereogum's list of the 5 best song of the week.[80] Complex and Pitchfork both included it on their lists of the best songs of the month (January 2017).[81][82] The A.V. Club included it on their list entitled "The A.V. Club’s songs of the summer 2017 for indoor kids".[83] The second single, "Ravens", was released on February 15, 2017, along with a music video uploaded to Mount Eerie's official YouTube account.[84] The video consists of old camcorder recordings of natural landscapes[85] and Elverum and Castrée.[84] It once again earned the "Best New Track" distinction from Pitchfork[63] and appeared on their list of the best songs of the month (February 2017).[86] It was ranked number 1 on Stereogum's list of the 5 best song of the week.[87] Elverum also did several interviews[lower-alpha 5] which he found to be "mentally draining". He did admit that he treated them as pseudo-therapy sessions, noting they were different from a typical PR campaign.[60]

Tour

Following the release of the album, Elverum embarked on a short North American tour in April 2017.[84] This was followed by another North American tour in September 2017, playing solo shows accompanied only by his acoustic guitar in intimate venues that included "concert halls, churches, and theaters".[88] The tour was extended to include Europe in November 2017.[89] While performing at Jacobikerk as part of Le Guess Who? festival in Utrecht, a sound engineer recorded Elverum's set without his knowledge. Elverum liked the recording so much that it was subsequently released as the live album (after) in 2018.[90]

The April, September-November tour received critical acclaim. Aaron Sharpsteen of SSG Music praised the show played at Mississippi Studios, calling it a "sea of collective melancholy".[91] Jochan Embley of The Independent awarded the show performed at St John on Bethnal Green church five stars and wrote that Elverum "plays and sings with such softness and space that you can hear the hum of his monitors as he does so".[92] Adam O'Sullivan of the Evening Standard described the show as "something truly remarkable, truly honest and something that those in attendance are unlikely ever to see again".[93] Woody Delaney of Loud and Quiet praised the show performed at Left Bank, Leeds calling it an "experience so human, it serves to remind the audience to cherish the fragility of life, and more immediately the person sat next to them".[94]

Aaron Badgley of Spill Magazine praised the show at the Great Hall, Toronto, Canada, calling it "one of the most memorable performances" he has seen and concluding that "the opportunity to see him do this live was one of those rare instances in life when you witnessed something truly important on stage".[95] Sarah Greene of Now Toronto echoed similar sentiments describing the show as "painfullly intimate", saying that, "In his solo performance, Phil Elverum showed that both songwriting and grieving are an ongoing process".[96] Braeden Halverson of Spotlight Ottawa wrote in his review of the show performed at St Albans Church that "seeing Phil live was one of the most unique, serene and emotionally impactful concert experiences I have had, and probably will ever have" but noted that it was "difficult" to say he enjoyed it.[97] Anna Alger of Exclaim! rated the show performed Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver 8/10 saying that "The intimacy of Elverum's offering at Christ Church Cathedral was welcomed, as difficult as it was to confront A Crow Looked at Me's stark lyricism."[98] Zach Buckner writing for Tiny Mix Tapes, noted in his review of the show performed at the Murmmr Theatre that the audience "listened attentively, awaiting the next dictum of living with death. No one had their phones out. No one dared murmur during a song."[99] David Farrow described the show as "A whisper to the audience. A secret that I feel compelled to share." writing that

As I grasp for conclusions, I want to wander to a comment on care or community, but that would miss the point. There cannot be a conclusion derived from pure absence. There can only be the experience. Thank you [Elverum] for the gift of this experience.[100]

Pitchfork writer Quinn Moreland named the show as her favourite of 2017. Describing the concert as "a wake—a spiritual sensation that was amplified by the venue, a temple."[101]

Elverum found that because of the personal nature of the songs touring was difficult, saying it felt like he was "going out there and re-enacting a trauma and charging people money for it" and criticising the sense of voyeurism the audience part took in.[21] He did admit though that he would "probably be in the audience too, if it were somebody else doing it. It's hard to look away from a car accident."[32]

| Date (2017)[102][103][84] | City[102][103][84] | State[102][103][84] | Country[102][103][84] | Venue or event[102][103][84] | Support | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April tour | ||||||

| April 4 | Eugene | Oregon | America | WOW Hall | — | [84] |

| April 6 | Big Sur | Califonia | Henry Miller Library | — | ||

| April 9 | Santa Ana | Observatory (When We Were Young Fest) | — | |||

| April 10 | San Diego | Irenic | — | |||

| April 11 | Los Angeles | The Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever | — | |||

| April 14 | Oakland | Starline Social Club | — | |||

| April 17 | Portland | Oregon | Mississippi Studios | Lori Goldston[91] | ||

| April 18 | Olympia | Washington | Obsidian | — | ||

| April 27 | Portland | Oregon | Amp Fest | — | [104] | |

| May 12-14 | Arcosanti | Arizona | FORM | — | [84] | |

| September tour: Leg 1 — North America[102] | ||||||

| August 18 | Vancouver | British Columbia | Canada | Christ Church Cathedral | Nicholas Krgovich[98] | [102] |

| September 5 | Chicago | Illinois | America | Thalia Hall | — | |

| September 7 | Raleigh | North Carolina | Fletcher Theatre (Hopscotch Music Festival) | — | ||

| September 8 | Washington | — | St. Stephen and the Incarnation Episcopal Church | — | ||

| September 11 | Brooklyn | New York | Union Temple of Brooklyn (Murmrr Theatre) | — | ||

| September 13 | Boston | Massachusetts | Arts at the Armory | — | ||

| September 15 | Providence | Rhode Island | Columbus Theatre | — | ||

| September 16 | Burlington | Vermont | Winooski United Methodist Church | — | ||

| September 17 | Montreal | Quebec | Canada | Ukrainian Federation Hall (Pop Montreal) | — | |

| September 20 | Toronto | Ontario | Great Hall | — | ||

| September 21 | Sandy Hill | Ottawa | St Alban's Church | Amanda Lowe | [97] | |

| Leg 2 — Europe[103] | ||||||

| November 3 | Krakow | — | Poland | Małopolski Ogród Sztuki | — | [103] |

| November 5 | Berlin | — | Germany | Silent Green | — | |

| November 6 | ||||||

| November 7 | Copenhagen | — | Denmark | Jazzhouse | — | |

| November 8 | ||||||

| November 10 | Utrecht | — | The Netherlands | Le Guess Who! Festival | — | |

| November 11 | Brussels | — | Belgium | Les Brigittines | — | |

| November 13 | London | — | England | St. John at Bethnal Green | — | |

| November 14 | ||||||

| November 15 | Leeds | — | Left Bank | — | ||

| November 16 | Glasgow | — | Scotland | Saint Luke's | — | |

| November 18 | St. Denijs | — | Belgium | St. Dyonisus | — | |

| November 20 | Oslo | — | Norway | Kulturkirken Jakob | — | |

| November 23 | Kristiansand | — | Vaktbua | — | ||

| November 25 | Stavanger | — | Kunsthallen | — | ||

| November 26 | Bergen | — | Landmark | — | ||

Reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AnyDecentMusic? | 8.8/10[105] |

| Metacritic | 93/100[106] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | A−[107] |

| Consequence of Sound | A−[17] |

| Exclaim! | 9/10[108] |

| Mojo | |

| Paste | 9.2/10[110] |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[33] |

| PopMatters | 10/10[29] |

| Uncut | 9/10[111] |

| Vice (Expert Witness) | A[112] |

Critical reception

A Crow Looked at Me received widespread critical acclaim upon its release. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from music critics, the album received an average score of 93, indicating "universal acclaim", based on 18 reviews.[106] Aggregator AnyDecentMusic? gave A Crow Looked At Me 8.8 out of 10, based on their assessment of the critical consensus.[105] According to Patrick Lyons of Sterogum A Crow Looked at Me received more attention than any previous Mount Eerie or Microphones album (including his 2001 cult classic The Glow Pt. 2).[113] Elverum found the album's reception "reaffirming" but was frustrated by those who viewed it as a tribute to his wife and felt uneasy about the album being public at all.[4][9]

Heather Phares from AllMusic called the album "remarkably powerful and pure".[53] Consequence of Sound's David Sackllah said that it was "overwhelming and humbling" and wrote that "A Crow Looked at Me stands as a remarkable example of the restorative power of music, an intimate display of love, daring both in concept and execution."[17] Zack Fenech of Exclaim! said that "this record possesses immense power to make listeners reflect on their own relationships and mortality. A Crow Looked at Me is a grim memento of the grand injustice of losing those most precious to us."[108] Paste's Matt Fink said that it was "beautifully and simply arranged, but ... not an entertaining album to listen to in any conventional sense, nor can it be shaken off easily." He added it made all other albums "seem frivolous" and that "there is no album quite like it."[110]

Ben Malkin of GIGsoup described the album as "art in its most pure, human form", a "showcase of weakness and cruel reality, prose of lost love," and "perhaps the saddest album ever made".[114] In his review for Spectrum Culture John Paul said that "Heartbreaking doesn't even begin to describe A Crow Looked at Me" and described the album as "pure grief delivered in a voice in which you can hear the weight of loss".[28] Jacopo Sanna of Arena Music claimed that A Crow Looked at Me is "probably the most important album about death and loss ever recorded".[115] Sarah Greene writing for Now Toronto described the album as "a lovingly crafted album, with gentle melodies that linger in the air, pretty, memorable guitar lines and a subtle but persistent approach to percussion". She concluded that despite it being an uncomfortable and harrowing listen, it was also a "tribute to an amazing 13-year love story".[2] Brian Roesler of Treblezine enjoyed the record considerably but demanded that readers, "Don't call it art. Don't call it music even. Call it a documentation of suffering and loss as an experience, and treat it as such".[49][lower-alpha 6] In an essay written for The Spinoff, Murdoch Stephens compared A Crow Looked At Me to the poetry of Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi and pondered how the listener should interact with a piece of art of such a visceral nature. The article called Elverum "the saddest musician in the world".[116] Elverum rejected the title, calling it absurd, and saying he sought to inject beauty into the record.[4]

Some reviewers wrote it was difficult to review the album. In his positive review for Drowned in Sound, JR Moores did not give the album a score because "even awarding this work the full ten-out-of-ten would feel too callous given the tragic circumstances of the record's gestation and its heartbreaking subject matter."[117] Reviewer Matthew Smith of No Ripcord said that "assigning a score to a project like this is reductive ... it's almost insulting to rank something as open and raw as this."[118] PopMatters reviewer Thomas Britt called the album a "masterpiece" but noted that it went beyond "the limits of conventional music criticism."[29] Marvin Lin from Tiny Mix Tapes did score the album but said that his rating meant "absolutely nothing".[14] Lucas Koprowski from Atwood Magazine wrote that "Breaking down any of these tracks for you would not only disrespect the meaning behind this album, but force you to swallow my interpretation of his words into a silence that is bottomless and real."[119] While reviewing a live performance of the album, Jochan Embley of The Independent commented that it "feels weird giving a star rating to another human's honest and unshrinking account of loss".[92]

Fan reception

In an interview with Pitchfork, Elverum recalled how fans reached out to him, relating to his story: "People have reached out in a new way. It happens in letters and emails, but also at the merch table. At almost every show, actually, someone would come up to me with tears in their eyes". Initially, Elverum found the interactions to be helpful and "mutually beneficial" however over time he began to find them overwhelming feeling as if he was failing those who sought help from him by not wishing to be a "hub of sorrow".[120][121]

Sarah Greene of Now Toronto commented on the disconnect between Elverum's audience at a live show and the deeply personal nature of the show writing:

the unsettling part of the show was: where does his adoring, emotional audience fit into all of it? On the one hand, being there and buying his merch may be the best way a fan can support the now single dad; but on the other, it points to the complicated relationship between deeply personal struggles and commerce, the merchandise we are left with after the fact.[96]

Elverum shared a similar sentiment, once commenting "This is kind of fucked up, isn’t it? I mean, I’m here telling you Death is real and you’re applauding."[91]

Accolades

A Crow Looked at Me appeared on numerous year-end top lists.[122] Such as The Atlantic,[123] Clash,[124] Consequence of Sound,[125] Earbuddy,[126] Exclaim!,[127] Fact,[128] The Guardian,[129] Paste,[130] Pigeons & Planes,[131] Pitchfork,[132] Popmatters,[133] Portland Mercury,[134] Noisey,[135] No Ripcord,[136] NPR,[137] Spectrum Culture,[138] Spin,[139] Sputnikmusic,[140] Stereogum,[141] Tiny Mix Tapes,[142] Under the Radar[143] and The Village Voice.[144]

It was also ranked one of the best albums of the decade by several publications: Noisey ranked it 17,[145] All Things Loud 18,[146] Tiny Mix Tapes 22,[147] Treblezine 32,[148] Stereogum 35,[149] Pitchfork 45,[150] Consequence Of Sound 54,[151] Portland Mercury and Melisma Magazine also included the album on their lists.[152][153]

The lead single "Real Death" also appeared on numerous year-end lists. It was ranked 14 by Pitchfork,[154] 31 by NME,[155] 41, by Spin,[156]48 by Treblezine[157] and 141 by Stereogum.[158] It was also ranked 66 on Treblezine's top 150 Songs of the 2010s.[159] "Ravens" and "Soria Moria" were included on Tiny Mix Tapes' list of their favoutite songs of 2017 and the decade respectively.[160][161]

Metacritic, which collates reviews of music albums, named it the second best-reviewed album of 2017,[122] the seventh best-reviewed album of the decade[162][lower-alpha 7] and the fifteenth best-reviewed album of all time.[163] According to Acclaimed Music, the album is the eleventh most critically acclaimed album of 2017.[164][lower-alpha 8] The album is the eleventh highest-rated album on AnyDecentMusic?.[166]

In an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Elverum discussed how he found it "absurd" that the album "was on all these critics' lists compared and ranked next to other people's albums about other things." Describing it as "off in its own universe."[32]

Legacy

Simon Kirk of the music review site Getintothis called the album and its companion piece Now Only "seminal".[167] Adam Nizum of Paste magazine described the album as "Historic".[168] Thomas Britt of Popmatters called A Crow Looked at Me "one of the most remarkable folk albums ever produced".[169] David Connolly of Odyssey wrote that "no other [album] really captures loss of a loved one in quite the same manner".[170] Sean Nelson of The Stranger called A Crow Looked at Me "an astonishing artistic and human achievement" which "makes beggars" of similar art that deals with bereavement and grief such as Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse, Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking, Lou Reed's Magic and Loss and Eric Clapton's Tears in Heaven by its frank and literal depiction of death and grief.[171] Music Critic Brendan Frank called the album a "must-listen" "for anyone who was ever remotely interested in Mount Eerie or The Microphones".[172] Jacob Nierenberg writing for Treblezine listed the album as one the of "10 Essential Home-Recorded Albums".[173] The album was included on Discogs' list of the "most miserably sad" albums of all time.[174] Donovan Farley of Willamette Week chose the opening track "Real Death" as one of Elverum's "essential" songs; Morgan Enos chose "Swims" in his ranking of Elverum's essential songs for Billboard.[175][176]

American rapper Danny Brown called the album as his favourite of 2017. Elverum thanked Brown and said that his recommendation was "more valuable (in real money sales) than The New York Times[']."[177] Michelle Zauner of Japanese Breakfast fame chose A Crow Looked at Me as one of the five albums that changed her life telling Tidal: "I've never heard something so personal, so vulnerable and just very sad. I related to it so much, and I felt like he expressed things and described moments between [his wife and him] that resonated with me and my own experience losing my mother".[178]

Writer Max Porter praised the album saying, that "[It] is so immaculately beautiful. It is so caring and sweet and soft and sad. There could not have been a better pairing [with Grief Is The Thing With Feathers.]"[179] Gus Lobban of Kero Kero Bonito compared the central theme of A Crow Looked at Me to the central theme of Time 'n' Place, the band's second studio album: "It's an example of a record by an artist who is exploring darker themes in front of a wider audience, defining this zeitgeist of people talking about depression. Time 'n' Place is informed by similar things to a record like that."[180] Gilles Demolder of black metal band Oathbreaker praised the album, looking to it for inspiration and crediting the album with helping him see that "acoustic guitar and words can be so much heavier than anything I've heard before".[181] Ben Walsh of Tigers Jaw described the album as "a crushingly real account of coming to terms with the death of a loved one" and its lyrics "soul-crushingly honest".[182]

Track listing

All tracks are written and produced by Phil Elverum.[117][183]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Real Death" | 2:27 |

| 2. | "Seaweed" | 3:01 |

| 3. | "Ravens" | 6:39 |

| 4. | "Forest Fire" | 4:15 |

| 5. | "Swims" | 4:07 |

| 6. | "My Chasm" | 2:22 |

| 7. | "When I Take Out the Garbage at Night" | 2:25 |

| 8. | "Emptiness pt. 2" | 3:28 |

| 9. | "Toothbrush/Trash" | 3:52 |

| 10. | "Soria Moria" | 6:33 |

| 11. | "Crow" | 2:21 |

| Total length: | 41:30 | |

Personnel

Credits adapted from the album's liner notes and Cult MLT.[9][184]

- Phil Elverum – songwriting – vocals – production – acoustic guitar – electric guitar – drum machine – bass – piano – accordion

- John Golden – Mastering, Lacquer Cut

- Other [Poem By] – Joanne Kyger

Release history

| Region | Label | Format | Category | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | P. W. Elverum & Sun, Ltd. | Double LP, Digital Download | ELV040 | [185] |

| Japan | P. W. Elverum & Sun, Ltd. | CD | EPCD101 |

Notes

- Elverum recorded some of the songs with her sleeping 10 feet away.[18]

- Kyger died of lung cancer two days before the album's release.[23][27]

- Elverum also remembers her as a foxglove in Haida Gwaii and a fly in his house.[31]

- Used in his 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. The Aura, as defined by the Tate institute is "is a quality integral to an artwork that cannot be communicated through mechanical reproduction techniques – such as photography".[69]

- Elverum once gave five interviews in one day.[60]

- A sentiment echoed by Elverum himself.[33]

- Its appearance on the list made it the highest rated folk album of the decade.[162]

- The tenth-highest ranking for an indie folk album.[165]

References

- Yoo, Noah (July 10, 2016). "Geneviève Elverum Has Died". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Greene, Sarah (March 27, 2017). "Mount Eerie's A Crow Looked At Me is unsettlingly personal". Now. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Gormely, Ian (November 5, 2018). "Microphones, Mount Eerie and Melancholy: The Career of Phil Elverum". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Kornhaber, Spencer (March 14, 2018). "The Pointlessness and Promise of Art After Death". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- Pearce, Sheldon (January 25, 2017). "Mount Eerie Announces New Album, Shares New Song 'Real Death'". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- "Mount Eerie Reveals Deeply Personal Album, A Crow Looked At Me". Self-Titled. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Ford Smith, Smith (September 6, 2017). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Reflects on Recent Grief, Relative Success, and the Power of Cosmic Forces". Indy Week. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Martin, Erin Lyndal (March 21, 2017). "Mount Eerie on Intimate Grief and the Creative Impulse". Bandcamp. Archived from the original on November 29, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- Burtan, Donovan (September 12, 2017). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum on music and grief". Cult MTL. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Stosuy, Brandon (March 15, 2017). "Phil Elverum on creating art from grief". The Creative Independent. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Greene, Jayson (March 13, 2017). "Death Is Real: Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Copes With Unspeakable Tragedy". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- Jesse Thorn (April 24, 2017). "Werner Herzog and Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum". Maxiumin Fun (Podcast). Bullseye with Jesse Thorn. Event occurs at 24:37-25:20. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Gallacher, Alex (January 26, 2017). "Mount Eerie Shares Song From New Album: Real Death". Folk Radio. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Lin, Marvin (2017). "Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked At Me". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- Will James (May 19, 2018). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Shares A Tiny Room With Death" (Podcast). KNKX. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Will James (May 19, 2018). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Shares A Tiny Room With Death" (Podcast). KNKX. Event occurs at 8:42. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Sackllah, David (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked at Me". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Marrs, Cypress (March 24, 2017). "Un-treasured Time: A Conversation with Phil Elverum". Los Angeles Review of Books. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Garvey, Meghan (March 28, 2017). "Phil Elverum On Life, Death And Meaninglessness". MTV. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Porter, Christa; Porter, Richard (March 19, 2018). "An Interview With Phil Elverum of Mount Eerie". Live In Everett. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Mount Eerie is not just poking at sadness". ABC. January 23, 2018. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Bowe, Miles (January 25, 2017). "Mount Eerie addresses his wife's death on new album A Crow Looked At Me". Fact. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Joffe, Justin (March 21, 2017). "Beyond Grief: How Mount Eerie Made an Album About His Wife's Death". The Observer. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Jesse Thorn (April 24, 2017). "Werner Herzog and Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum". Maxiumin Fun (Podcast). Bullseye with Jesse Thorn. Event occurs at 29:30-30:30. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Walker, Erin (September 12, 2017). "How Mount Eerie copes with personal grief". The Concordian. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Fox, Emily (February 13, 2020). "Music Heals: Phil Elverum on Expressing Grief Through Music and Remembering His Late Wife Geneviève Castrée". KEXP. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- John McMurtie (March 23, 2017). "Joanne Kyger, trailblazing Beat poet, dies at 82". San Francisco Gate. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Paul, John (March 28, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". Spectrum Culture. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Britt, Thomas (March 20, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Caramanica, Jon (March 22, 2017). "The Sound of Sadness Overwhelms and Inspires Mount Eerie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- Sanna, Jacopo (March 30, 2017). "A Crow Looked At Me: Death and Nature on New Mount Eerie Album". Arena. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Sun, Michael (January 23, 2018). "Mount Eerie on grief, loss, and self-flagellation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Powell, Mike (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked At Me". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Roberts, Christopher (June 4, 2020). "Mount Eerie Shares Video for Devastating New Song, "Ravens," and Announces Tour". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Greene, Phillip (March 30, 2017). "'A Crow Looked at Me' By Mount Eerie – An Album Review". Cistern Yard. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Guarna, Tomas (April 5, 2017). "Emotions Fly in 'A Crow Looked At Me'". The Heights. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Baker, Peter C (September 6, 2017). "In A Room Listening To Phil Elverum Sing About His Wife's Death". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Hann, Michael (November 14, 2017). "Mount Eerie review – truth defeats beauty on stark songs of death". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Zavada, Eric (2017). "Death is Real: Mount Eerie and the Art of Expressing 'Emptiness' through Songwriting". Berklee. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Gotrich, Lars (March 16, 2017). "Review: Mount Eerie, 'A Crow Looked At Me'". NPR. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Budgor, Zach (March 21, 2017). "In Search of a New Way to Grieve". Hazlitt. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Geller, Mason (April 9, 2017). "Mount Eerie - A Crow Looked At Me". The Riverdale Review. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Breihan, Tom (March 21, 2017). "Album Of The Week: Mount Eerie A Crow Looked At Me". Stereogum. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Salmon, Ben (April 12, 2017). "On A Crow Looked at Me, Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Processes the Death of His Wife". Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Corcoran, Nina (March 24, 2017). "Craig Finn, Mount Eerie, Pallbearer, and more in this week's music reviews". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "A Crow Looked at Me Gives Mount Eerie a Worthy Eulogy". Beatroute. August 12, 2017. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Tom Power (July 4, 2017). "July 4: How music helped Phil Elverum grieve his wife's death" (Podcast). WNYC. Event occurs at 10:12-10:30. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Doolin, Jake (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie - A Crow Looked At Me (Album Review)". VultureHound. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Roesler, Brian (2017). "Mount Eerie A Crow Looked At Me Review". Treblezine. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Fink, Matt (July 18, 2017). "Mount Eerie Beyond Words". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Hilla, Kurki (2018). "Notes on loss and photography". Aalto University. Retrieved April 19, 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Elder, Drew (April 4, 2017). "Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked at Me". WUOG. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Phares, Heather (2017). "A Crow Looked at Me – Mount Eerie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Cherchenko, Luke (March 31, 2018). "Mount Eerie – Now Only". WIUX. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Grasping at the Echoes: An Interview with Phil Elverum Mount Eerie's "A Crow Looked At Me" and the Struggle of Articulating Real Death". Cooper Point Journal. May 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Huffman, Haley (September 8, 2017). "Album Review: "A Crow Looked at Me" by Mount Eerie". WXJM. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Jones, Tristan (March 18, 2017). "A Crow Looked At Me". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Beauchemin, Molly (May 28, 2017). "Mount Eerie's 'Seaweed' Is A Heartbreaking Reflection on Love, Death, and Nature". Garden Collage. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- Barrons J., Ethan (April 14, 2017). "Review: Mount Eerie — 'A Crow Looked at Me'". Northwest Music Scene. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Salmon, Ben (April 12, 2017). "On A Crow Looked at Me, Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Processes the Death of His Wife". Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Elverum, Phil (December 15, 2017). "Class of 2017 – The 100 greatest songs of the year!". Songs For Whoever. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Morehead, Jason (April 14, 2017). "Mount Eerie's A Crow Looked at Me Confronts the Horror of Death". Christ and Pop Culture. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- Sodomsky, Sam (February 15, 2017). "'Ravens' by Mount Eerie Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Abebe, Nitsuh (April 4, 2017). "New Sentences: From 'Forest Fire,' by Mount Eerie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Smith, Matthew (March 23, 2017). "A Crow Looked at Me". No Ripcord. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Gonzalez, Sean (April 7, 2017). "Review: Mount Eerie – 'A Crow Looked At Me'". The Alternative. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Hardaway, Grant (March 26, 2017). "Mount Eerie – A Crow Looked at Me". Radio UTD. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Spencer, Matthew (May 2, 2009). "Phil Elverum, 'Dawn: Winter Journal'". Brainwash. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- "AURA". Tate institute. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Richards, Sam (August 14, 2018). "Hear a track from Mount Eerie's new live album". Uncut. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Currin, Grayson (March 28, 2017). "How Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Faced Grief on His Devastating New Album". Vice. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- Yoo, Noah (January 5, 2017). "Phil Elverum: 'Please Don't Come' to Tomorrow's Mount Eerie Show". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Grandy, Eric (January 31, 2017). "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Devastates With His First Show in Two Years". The Stranger. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "P", "Mr" (January 3, 2017). "Mount Eerie to play 11 new songs at first show in over 2 years on Friday". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Strauss, Matthew (December 30, 2016). "Mount Eerie Performing New Music at First Show in 2 Years". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Child, Tom (April 10, 2017). "Mount Eerie: Stay Sincere". L.A. Record. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- Yoo, Noah (January 20, 2017). "Mount Eerie, Pains of Being Pure at Heart, More on New ACLU Benefit Album: Listen". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 16, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Currin, Grayson (January 25, 2017). "'Real Death' by Mount Eerie Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Mandel, Leah (January 31, 2017). "13 Songs You Need In Your Life This Week". The Fader. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "The 5 Best Songs Of The Week". Stereogum. January 27, 2017. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Planes & Pigeons Staff (January 27, 2017). "Best Songs of the Month (Jan 2017)". Complex. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Lozano, Kevin; Jarnow, Jesse; Anderegg, Brendon (February 7, 2017). "Best New Tracks of January 2017". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- O'Neal, Sean (August 6, 2018). "The A.V. Club's songs of the summer 2017 for indoor kids". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Rohrback, Paul (February 15, 2017). "Mount Eerie Releases Devastating 'Ravens' Video, Announces West Coast Tour Dates". Paste. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- Wyatt, John (February 16, 2017). "WATCH: Mount Eerie Releases New Video for "Ravens" and Announces Spring 2017 Tour -". Mxdwn. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Kahn, Faye; Curtin, Jeff (March 1, 2017). "Best New Tracks: February 2017". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- "The 5 Best Songs Of The Week". Stereogum. February 17, 2017. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Geslani, Michelle (May 31, 2017). "Mount Eerie announces North American tour dates". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Smart, Dan (September 20, 2017). "Mount Eerie announces European tour dates in November". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Reese, Nathan (October 1, 2018). "Mount Eerie: (after)". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Sharpsteen, Aaron (April 18, 2017). "Show Review: Mount Eerie and Lori Goldston at Mississippi Studios". SSG Music. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Embley, Jochan (November 14, 2017). "Mount Eerie, St John on Bethnal Green, gig review: Beautiful art inspired by tragedy". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 24, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- O'Sullivan, Adam (November 17, 2017). "Mount Eerie at St John on Bethnal Green: A truly remarkable and honest portrayal of tragedy". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Delaney, Woody (November 16, 2017). "The sobering appreciation that comes from Mount Eerie's devastating grief". Loud and Quiet. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Badgley, Aaron. "Spill Live Review: Mount Eerie @ Great Hall Toronto". Spill Magazine. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Greene, Sarah (September 21, 2017). "Mount Eerie's Great Hall concert was painfully intimate". Now Toronto. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Halverson, Braeden (September 21, 2017). "Mount Eerie delivers emotionally impactful concert at St Albans Church". Spotlight Ottawa. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Alger, Anna (August 19, 2017). "Mount Eerie / Nicholas Krgovich Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver BC, August 18". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Buckner, Zach (September 18, 2017). "Mount Eerie Murmrr Theatre; Brooklyn, NY". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Farrow, David (September 19, 2017). "Mount Eerie Murmrr Theatre; Brooklyn, NY". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Moreland, Quinn (December 12, 2017). "11 Pitchfork Staffers on Their Favorite Live Shows of 2017". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Geslani, Michelle (May 31, 2017). "Mount Eerie announces North American tour dates". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Smart, Dan (September 20, 2017). "Mount Eerie announces European tour dates in November". Tinymixtapes. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "Amp Fest". Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "A Crow Looked at Me by Mount Eerie reviews". AnyDecentMusic?. Archived from the original on May 28, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Reviews and Tracks for A Crow Looked at Me by Mount Eerie". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Corcoran, Nina (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie confronts death on its saddest album to date". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Fenech, Zach (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Male, Andrew (July 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". Mojo (284): 91.

- Fink, Matt (March 24, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked At Me Review". Paste. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Sodomsky, Sam (May 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". Uncut (240): 35.

- Christgau, Robert (January 27, 2018). "Robert Christgau on Mount Eerie's 'A Crow Looked at Me,' a Brutal Listen". Vice. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Lyons, Patrick (March 14, 2018). "Phil Elverum On Critical Acclaim, Lil Peep, & Mount Eerie's New Album Now Only". Stereogum. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Malkin, Ben (April 3, 2017). "Mount Eerie 'A Crow Looked at Me'". Gigsoup. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Sanna, Jacopo (March 28, 2018). "Mount Eerie Explores Everything That's Left to Remember". Arena Music. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Stephens, Murdoch (January 15, 2018). "How to listen to Mount Eerie, the saddest musician in the world". The Spinoff. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Moores, JR (March 20, 2017). "Mount Eerie - A Crow Looked at Me". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on November 29, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- Smith, Matthew (March 23, 2017). "Mount Eerie: A Crow Looked at Me". No Ripcord. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- Koprowski, Lucas (June 2, 2017). "Our Take: Mount Eerie Transmit Devastation With 'A Crow Looked At Me'". Atwood Magazine. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- November 12, 2019. "Mount Eerie's Phil Elverum Starts Over, Again". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Brodsky, Rachel (April 4, 2017). "When Words Fail: Phil Elverum Navigates Life After Death". Paste. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Dietz, Jason (December 21, 2017). "The Best Albums Of 2017". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Kornhaber, Spencer (December 12, 2017). "The 10 Best Albums of 2017". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Clash Staff (December 19, 2017). "Clash Albums Of The Year 2017". Clash. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Cos Staff (December 26, 2017). "Top 50 Albums of 2017". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Krenn, Nick (December 11, 2017). "Earbuddy's 100 Best Albums of 2017". Earbuddy. Archived from the original on July 15, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Staff, Exclaim! (December 4, 2017). "Top 10 Folk and Country Albums of 2017". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Horner, Al (December 20, 2017). "The 50 best albums of 2017". Fact. Archived from the original on December 20, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Guardian staff (December 5, 2017). "The Best Albums Of 2017". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Paste staff (November 27, 2017). "The 50 Best Albums of 2017". Paste. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Price, Joe (December 21, 2017). "Best Albums of 2017". Pigeons & Planes. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Pitchfork Staff (December 12, 2017). "The 50 Best Albums of 2017". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Britt, Thomas (December 11, 2017). "The 60 Best Albums of 2016". Popmatters. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Crowell, Cameron (December 20, 2017). "The Best Records of 2017". Portland Mercury. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Joyce, Joyce (December 6, 2017). "The 100 Best Albums of 2017". Noisey. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Coleman, David (December 18, 2017). "The Best Albums Of 2017". No Ripcord. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- NPR Staff (December 12, 2017). "The 50 Best Albums Of 2017". NPR. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Spectrum Culture Staff (December 19, 2017). "Top 20 Albums of 2017". Spectrum Culture. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Berman, Judy (December 18, 2017). "50 Best Album of 2016". Spin. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Robertson, Alex (December 21, 2017). "Staff's Top 50 Albums of 2017: 30 – 11". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Stereogum Staff (December 5, 2017). "The 50 Best Albums of 2017". Stereogum. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- TMT Staff (December 18, 2017). "2017: Favorite 50 Music Releases". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Wyatt, Stephen (December 30, 2017). "Under the Radar's Top 100 Albums of 2017". Under the Radar. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- The Editors (January 22, 2018). "Pazz & Jop: It's Kendrick's and Cardi's World. We're All Just Living in It". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Joyce, Colin (November 6, 2019). "The 100 Best Albums of the 2010s". Noisey. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Parker, Jack (December 5, 2019). "All Things Loud's Album Of The Decade:The Top 20". All Things Loud. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- TMT Staff (December 19, 2019). "2010s: Favorite 100 Music Releases of the Decade". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Roesler, Brian (January 7, 2020). "Top 150 Albums of the 2010s". Treblezine. Archived from the original on May 3, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "The 100 Best Albums Of The 2010s". Stereogum. November 4, 2019. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "The 200 Best Albums of the 2010s". Pitchfork. October 8, 2019. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- Melis, Matt (December 30, 2019). "Top 100 Albums of the 2010s". Consequence Of Sound. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- Terwillger, Chipp (December 19, 2019). "The Top 5 Albums of the 2010s (According to Mercury Editorial Staff)". Portland Mercury. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Norton, Mike (December 29, 2019). "Our Favourite Albums of the 2010s". Melisma Magazine. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- Sodomsky, Sam (December 9, 2017). "The 100 Best Songs of 2017". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- NME Staff (November 27, 2017). "Songs from 2017: the best of the year". NME. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Arcand, Rob (December 20, 2017). "The 101 Best Songs of 2017". Spin. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Aguilar, Ernesto (December 4, 2017). "Top 100 Songs of 2017". Treblezine. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- Helman, Peter (November 5, 2019). "The 200 Best Songs Of The 2010s". Stereogum. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Im, Jackie (January 6, 2020). "Top 150 Songs of the 2010s". Treblezine. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Jherwood, Soe (December 15, 2017). "2017: Favorite 50 Songs". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- Smart, Dan (December 19, 2019). "2010s: Favorite 100 Songs of the Decade". Tiny Mix Tapes. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Best Albums of the Decade (2010-2019)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Album Releases By Score". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Mount Eerie A Crow Looked at Me". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "Top Indie Folk Albums". Acclaimed Music. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "All Time Chart". AnyDecentMusic?. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Kirk, Simon (December 12, 2019). "Mount Eerie's A Crow Looked At Me and Now Only – tackling bereavement and mental health". Getintothis. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Nizum, Adam (July 11, 2017). "10 Historic Albums About the Loss of a Loved One". Paste. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Britt, Thomas (March 15, 2018). "Mount Eerie's Now Only Feels Like More of A Crow Looked at Me". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Connolly, David (September 20, 2017). "5 Albums That Are Guaranteed To Make You Cry". Odyssey. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Nelson, Sean (March 22, 2017). "Mount Eerie's A Crow Looked at Me Is the Most Exquisite Desolation You've Ever Heard". The Stranger. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Frank, Brendan (March 23, 2017). "Review: Mount Eerie, A Crow Looked at Me". Pretty Much Amazing. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- Nierenberg, Jacob (April 21, 2020). "10 Essential Home-Recorded Albums". Treblezine. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "The Most Miserably Sad Albums Of All-Time | Discogs Staff Picks". Discogs. January 23, 2019. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

|first=missing|last=(help) - Farley, Donovan (March 28, 2018). "Nine Essential Mount Eerie Songs". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Enos, Morgan (July 27, 2018). "8 Essential Tracks From Michelle Williams' Songwriter Husband Phil Elverum". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Danny Brown's Choice for Album of the Year is..." xdannyxbrownx. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Ehrlich, Brenna (July 14, 2017). "Japanese Breakfast: 5 Albums That Changed My Life". Tidal. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Franklin, Mj (August 10, 2017). "'Grief Is The Thing With Feathers' is a postmodern novel about grief, and it's so damn sad and so damn perfect". Mashable. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Sakiyama, Seiji (November 1, 2018). "Kero Kero Bonito talks pop, boring pop and Linkin Park". The Daily Californian. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Franklin, Dan (March 19, 2020). Heavy: How Metal Changes the Way We See the World. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-4721-3102-7. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Ben, Walsh (September 15, 2017). "From The Desk Of Tigers Jaw: Mount Eerie's "A Crow Looked At Me"". Magnet Magazine. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Tom Power (July 4, 2017). "July 4: How music helped Phil Elverum grieve his wife's death" (Podcast). WNYC. Event occurs at 10:00-10:12. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- A Crow Looked at Me (Media notes). Phil Elverum. P. W. Elverum & Sun, Ltd. 2017.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "A Crow Looked At Me by Mount Eerie". P.W. Elverum And Sun. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

External links

- A Crow Looked at Me at Discogs (list of releases)