3753 Cruithne

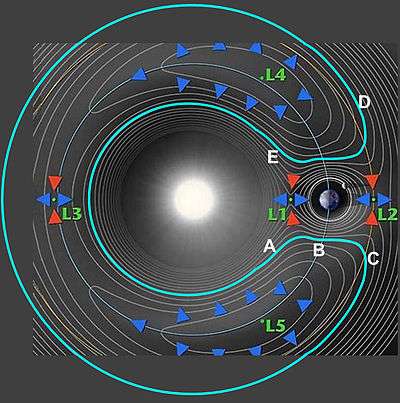

3753 Cruithne /kruˈiːnjə/ is a Q-type, Aten asteroid in orbit around the Sun in 1:1 orbital resonance with Earth, making it a co-orbital object. It is an asteroid that, relative to Earth, orbits the Sun in a bean-shaped orbit that effectively describes a horseshoe, and that can change into a quasi-satellite orbit.[3] Cruithne does not orbit Earth and at times it is on the other side of the Sun,[4] placing Cruithne well outside of Earth's Hill sphere. Its orbit takes it inside the orbit of Mercury and outside the orbit of Mars.[4] Cruithne orbits the Sun in about 1 year but it takes 770 years for the series to complete a horseshoe-shaped movement around the Earth.[4]

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Duncan Waldron |

| Discovery date | 10 October 1986 |

| Designations | |

| (3753) Cruithne | |

| Pronunciation | /kruˈiːnjə/[1] Irish: [ˈkrɪhnʲə], [ˈkrɪnʲə], or [ˈkrʊnʲə]; Old Irish: [ˈkruθʲnʲe] |

Named after | Cruthin |

| 1983 UH; 1986 TO | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| Epoch 4 September 2017 (JD 2458000.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 16087 days (44.04 yr) |

| Aphelion | 1.5114 AU (226.10 Gm) |

| Perihelion | 0.48405 AU (72.413 Gm) |

| 0.99774 AU (149.260 Gm) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.51485 (213000 wrt Earth)[lower-alpha 1] |

| 1.00 yr (364.02 d) | |

Average orbital speed | 27.73 km/s |

| 257.46° | |

| 0° 59m 20.436s / day | |

| Inclination | 19.805° |

| 126.23° | |

| 43.831° | |

| Earth MOID | 0.07119 AU (6,618,000 mi) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | ~5 km |

| Mass | 1.3×1014 kg |

| 27.30990 h (1.137913 d)[2] | |

| 0.15 | |

| Q | |

| 15.6[2] | |

The name Cruithne is from Old Irish and refers to the early Picts (Irish: Cruthin) in the Annals of Ulster[4] and their eponymous king ("Cruidne, son of Cinge") in the Pictish Chronicle.

Discovery

Cruithne was discovered on 10 October 1986 by Duncan Waldron on a photographic plate taken with the UK Schmidt Telescope at Siding Spring Observatory, Coonabarabran, Australia. The 1983 apparition (1983 UH) is credited to Giovanni de Sanctis and Richard M. West of the European Southern Observatory in Chile.[5]

It was not until 1997 that its unusual orbit was determined by Paul Wiegert and Kimmo Innanen, working at York University in Toronto, and Seppo Mikkola, working at the University of Turku in Finland.[6]

Dimensions and orbit

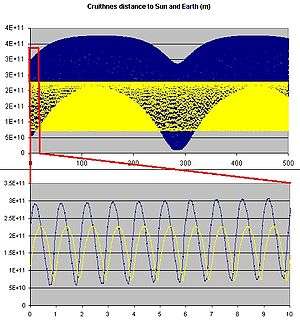

Sun · Earth · 3753 Cruithne

Cruithne is approximately 5 kilometres (3 mi) in diameter, and its closest approach to Earth is 12 million kilometres (0.080 AU; 7,500,000 mi), approximately thirty times the separation between Earth and the Moon. From 1994 through 2015, Cruithne made its annual closest approach to Earth every November.[7]

Although Cruithne's orbit is not thought to be stable over the long term, calculations by Wiegert and Innanen showed that it has probably been synchronized with Earth's orbit for a long time. There is no danger of a collision with Earth for millions of years, if ever. Its orbital path and Earth's do not cross, and its orbital plane is currently tilted to that of the Earth by 19.8°. Cruithne, having a maximum near-Earth magnitude of +15.8, is fainter than Pluto and would require at least a 320-millimetre (12.5 in) reflecting telescope to be seen.[8][9]

Cruithne is in a normal elliptic orbit around the Sun. Its period of revolution around the Sun, approximately 364 days at present, is almost equal to that of the Earth. Because of this, Cruithne and Earth appear to "follow" each other in their paths around the Sun. This is why Cruithne is sometimes called "Earth's second moon".[10] However, it does not orbit the Earth and is not a moon.[11] In 2058, Cruithne will come within 0.09 AU (13.6 million kilometres or 8.5 million miles) of Mars.[7]

Due to a high orbital eccentricity, Cruithne's distance from the Sun and orbital speed varies a lot more than the Earth's, so from the Earth's point of view Cruithne actually follows a kidney-bean-shaped horseshoe orbit ahead of the Earth, taking slightly less than one year to complete a circuit of the "bean". Because it takes slightly less than a year, the Earth "falls behind" the bean a little more each year, and so from our point of view, the circuit is not quite closed, but rather like a spiral loop that moves slowly away from the Earth.

After many years, the Earth will have fallen so far behind that Cruithne will then actually be "catching up" on the Earth from "behind". When it eventually does catch up, Cruithne will make a series of annual close approaches to the Earth and gravitationally exchange orbital energy with Earth; this will alter Cruithne's orbit by a little over half a million kilometres—while Earth's orbit is altered by about 1.3 centimetres (0.51 in)—so that its period of revolution around the Sun will then become slightly more than a year. The kidney bean will then start to migrate away from the Earth again in the opposite direction – instead of the Earth "falling behind" the bean, the Earth is "pulling away from" the bean. The next such series of close approaches will be centred on the year 2292 – in July of that year, Cruithne will approach Earth to about 12.5 million kilometres (0.084 AU; 7,800,000 mi).

After 380 to 390 years or so, the kidney-bean-shaped orbit approaches Earth again from the other side, and the Earth, once more, alters the orbit of Cruithne so that its period of revolution around the Sun is again slightly less than a year (this last happened with a series of close approaches centred on 1902, and will next happen with a series centered on 2676). The pattern then repeats itself.

Similar minor planets

_2010_SO16_orbit.gif)

More near-resonant near-Earth objects (NEOs) have since been discovered. These include 54509 YORP, (85770) 1998 UP1, 2002 AA29, and 2009 BD which exist in resonant orbits similar to Cruithne's. 2010 TK7 is the first and so far only identified Earth trojan.

Other examples of natural bodies known to be in horseshoe orbits (with respect to each other) include Janus and Epimetheus, natural satellites of Saturn. The orbits these two moons follow around Saturn are much simpler than the one Cruithne follows, but operate along the same general principles.

Mars has four known co-orbital asteroids (5261 Eureka, 1999 UJ7, 1998 VF31, and 2007 NS2, all at the Lagrangian points), and Jupiter has many (an estimated one million greater than 1 km in diameter, the Jovian trojans); there are also other small co-orbital moons in the Saturnian system: Telesto and Calypso with Tethys, and Helene and Polydeuces with Dione. However, none of these follow horseshoe orbits.

In popular culture

Cruithne plays a major role in Stephen Baxter's novel Manifold: Time, which was nominated for the Arthur C. Clarke Award for best science fiction in 2000.

Cruithne is mentioned on the QI season 1 episode "Astronomy", in which it is incorrectly described as a second moon of Earth. In a later episode, this mistake was rectified and it was added that Earth has over 18,000 mini-moons.

In Astonishing X-Men, Cruithne is the site of a secret lab assaulted by Abigail Brand and her S.W.O.R.D. team. It contains many Brood before Brand destroys it.[12]

In the Insignia trilogy, 3753 Cruithne has been moved into an orbit around Earth to serve as a training ground for the Intrasolar Forces. In the third novel, Catalyst, it is intentionally directed at the Earth. While it is destroyed before impact, its fragments rain down on the Earth's surface, killing nearly 800 million people across the world.

In the science-fiction book series Aeon 14, Cruithne appears as an inhabited moonlet, home to 'privateers', smugglers, Terran Space Fleet (TSF) outposts and corporate headquarters.[13] Notable inhabitants have included Ngoba Starl and Petral Dulan.[14]

See also

- 2006 RH120

- 2010 SO16

- Asteroids in fiction: Other asteroids, Asteroids in fiction: Colonization, and Asteroids in fiction: Mining

- Co-orbital configuration

- Earth's second moon

- Natural satellite

- Quasi-satellite

Notes

- Computed with JPL Horizons using a geocentric solution. Ephemeris Type: Orbital Elements / Center: 500 / Time Span: 2017-Sep-04 (to match infobox epoch)

References

- For instance, on the British television show Q.I. (Episode 2, Season 1; aired 11 Sept 2003).

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 3753 Cruithne (1986 TO)" (2017-11-02 last obs). Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Christou, A. A.; Asher, D. J. (2011). "A long-lived horseshoe companion to the Earth". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (4): 2965. arXiv:1104.0036. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.2965C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18595.x.

- Cruithne: Asteroid 3753 Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine. Western Washington University Planetarium. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Wiegert, Paul A. & Innanen, Kimmo (June 1998). "The Orbital Evolution of Near-Earth Asteroid 3753". The Astronomical Journal. 115 (6): 2604–2613. Bibcode:1998AJ....115.2604W. doi:10.1086/300358.

- Wiegert, Paul A.; et al. (12 June 1997). "An asteroidal companion to the Earth (letter)" (PDF). Nature. 387 (6634): 685–86. doi:10.1038/42662. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "JPL Close-Approach Data: 3753 Cruithne (1986 TO)" (2008-10-25 last obs). Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- "This month Pluto's apparent magnitude is m=14.1. Could we see it with an 11" reflector?". Singapore Science Centre. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- "The astronomical magnitude scale". The ICQ Comet Information Website. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- Lloyd, Robin. "More Moons Around Earth?". Space.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012.

- Meeus, reference above, writes "we may not deduce that Cruithne is a "companion" of the Earth, as some authors wrote, and certainly it is not a satellite! The object simply cannot be a satellite of the Earth, as it moves from nearly the orbit of Mercury to outside that of Mars, and because sometimes it is in superior conjunction, at the far side of the Sun as seen from the Earth".

- Astonishing X-Men vol. 3 #31

- Cooper, M. D. (2018), The Aeon 14 Reading Guide

- Aaron, James S.; Cooper, M. D. (2018), Lyssa's Dream, ISBN 9781973940906

Further reading

- Wiegert, Paul A.; Innanen, Kimmo A.; Mikkola, Seppo (1997). "An asteroidal companion to the Earth". Nature. 387 (6634): 685–686. doi:10.1038/42662.

- Meeus, Jean (2002). "Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit". More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels. Richmond, Virginia: Willmann-Bell. ISBN 978-0-943396-74-3.

External links

- Paul Wiegert's page about Cruithne, with movies

- Java-applet based animations showing Cruithne's orbit

- A simulation of Cruithne's orbit with animation (Gravity Simulator)

- Curious About Astronomy: Have astronomers discovered Earth's second moon?

- Interactive 3D gravity simulation of Cruithne's orbit

- 3753 Cruithne at NeoDyS-2, Near Earth Objects—Dynamic Site

- Ephemeris · Obs prediction · Orbital info · MOID · Proper elements · Obs info · Close · Physical info · NEOCC

- 3753 Cruithne at the JPL Small-Body Database