26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement (Spanish: Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26th July 1953 attack on the army barracks on Santiago de Cuba in an attempt to start the overthrowing of the dictator Fulgencio Batista.[1] Fidel Castro's left-wing nationalist ideology was founded in the liberal ideas of José Martí.

| 26th of July Movement | |

|---|---|

Movimiento 26 de Julio Participant in Cuban Revolution | |

A modern impression of one of the flags of the 26th of July Movement | |

| Active | 1955–1965 |

| Ideology | Anti-imperialism Left-wing nationalism Vanguardism |

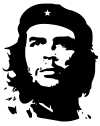

| Leaders | Fidel Castro (head) Raúl Castro Che Guevara Camilo Cienfuegos Juan Almeida Bosque |

| Headquarters | Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico (first) Havana, Cuba (second) |

| Area of operations | Caribbean Sea |

| Opponent(s) | Fulgencio Batista's Government, Cuban Army |

| Battles and war(s) | Operation Verano, Battle of La Plata, Battle of Las Mercedes, Battle of Yaguajay, Battle of Santa Clara |

| Cuban Revolution |

|---|

| Timeline |

| Events |

| People |

| Topics |

This is considered one of the most important organizations among the Cuban Revolution. At the end of 1956, Castro established a guerrilla base in the Sierra Maestra. This base defeated the troops of Batista on December 31, 1958, setting into motion the Cuban Revolution and installing a government led by Manuel Urrutia Lleó. The Movement fought the Batista regime on both rural and urban fronts. The movement's main objectives were distribution of land to peasants, nationalization of public services, industrialization, honest elections, and large scale education reform.

In July 1961, the 26th of July Movement was one of the parties that integrated into the Organizaciones Revolucionarias Integradas (ORI) of the Integrated Revolutionary Organization (IRO) as well as the Popular Socialist Party and the March 13 Revolutionary Directory. On March 26, 1962, the party dissolved to form the Partido Unido de la Revolución Socialista de Cuba (PURSC) or the United Party of the Socialist Revolution of Cuba (UPSRC), which held a communist ideology.[1]

Origins

The 26th of July Movement's name originated from the failed attack on the Moncada Barracks, an army facility in the city of Santiago de Cuba, on 26 July 1953.[2] This attack was led by a young Fidel Castro, who was a legislative candidate in a free election that had been cancelled by Batista.[3] The attack had been intended as a rallying cry for the revolution. Castro was captured and sentenced to 15 years in prison but, along with his group, was granted an amnesty after two years following a political campaign on their behalf. Castro traveled to Mexico to reorganize the movement in 1955 with several other exiled revolutionaries (including Raúl Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos, and Juan Almeida Bosque). Their task was to form a disciplined guerrilla force to overthrow Batista.

The original core of the group was organized around the attack on the Moncada Barracks merged with the National Revolutionary Movement led and Rafael García Bárcenas and with a majority of the Orthodox Youth. Soon after, National Revolutionary Action led by Frank País would join. Because of the commonality in their ideology and their goal of wanting to topple the Batista regime, the M-26-7 would quickly add more young people from diverse political backgrounds.

Role in the Cuban Revolution

On 2 December 1956, 82 men landed in Cuba, having sailed in the boat Granma from Tuxpan, Veracruz, ready to organize and lead a revolution. The early signs were not good for the movement. They landed in daylight, were attacked by the Cuban Air Force, and suffered numerous casualties. The landing party was split into two and wandered lost for two days, most of their supplies abandoned where they landed. They were also betrayed by their peasant guide in an ambush, which killed more of those who had landed. Batista mistakenly announced Fidel Castro's death at this point. Of the 82 who sailed aboard the Granma, only 12 eventually regrouped in the Sierra Maestra mountain range. While the revolutionaries were setting up camp in the mountains, "Civic Resistance" groups were formulating in the cities, putting pressure on the Batista regime. Many middle-class and professional persons flocked toward Castro and his movement.[4] While in the Sierra Maestra mountains the guerrilla forces attracted hundreds of Cuban volunteers and won several battles against the Cuban Army. Ernesto 'Che' Guevara was shot in the neck and chest during the fighting, but was not severely injured. (Guevara, who had studied medicine, continued to give first aid to other wounded guerrillas.) This was the opening phase of the war of the Cuban Revolution, which continued for the next two years. It ended in January 1959, after Batista fled Cuba for Dominican Republic, on New Year's Eve when the Movement's forces marched into Havana.

Political and Military Action

The guerrillas increased their ranks to 400 men in February 1958.[5] In comparison, the forces of Batista reached 50,000 men, but only 10,000 were able to be used at once to confront the guerrillas. Batista launched an offensive of 10,000 with air and land support to encircle and destroy the guerrillas hidden in the Sierra between April and August 1958, this campaign ended in a decisive failure for the development of the conflict.[6] Finally, after two years of war, the rebels defeated the Batista forces, causing them to flee to the Dominican Republic and take power January 1, 1959. At that time they added around 20,000 to 30,000 guerrillas and the war had cost the lives of between 1,000 and 2,500 people.

Post-1959

After the takeover, anti-Batistas, liberals, urban workers, peasants, and idealists became the dominant followers of the M-26-7 movement, which gained control over Cuba. The Movement was joined with other bodies to form the United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution, which in turn became the Communist Party of Cuba in 1965. Cuba modeled itself after the Eastern European nations that made up the Warsaw Pact, becoming the first socialistic government in the Americas. Once it was learned that Cuba would adopt a strict Marxist–Leninist political and economic system, opposition was raised not only by dissident party members, but by the United States as well.[7] Fidel Castro's government seized private land, nationalized hundreds of private companies—including several local subsidiaries of U.S. corporations—and taxed American products so heavily that U.S. exports were cut half in just two years. The Eisenhower Administration then imposed trade restrictions on everything except food and medical supplies. As a result, Cuba turned to the Soviet Union for trade instead. The US responded by cutting all diplomatic ties to Cuba, and have had a rocky relationship ever since.[8] In April 1961, a CIA-trained force of Cuban exiles and dissidents launched the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs Invasion against Cuba, shortly after Castro had declared the revolution socialist. After the invasion, Castro formally proclaimed himself a communist.

The flag of the 26th of July Movement is on the shoulder of the Cuban military uniform, and continues to be used as a symbol of the Cuban revolution.

See also

References

- Notes

- "26th of July Movement | Cuban history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Faria, Miguel A. "Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement," 27 July 2004. http://archive.newsmax.com/archives/articles/2004/7/27/110928.shtml Saved page https://web.archive.org/web/20081011015901/http://archive.newsmax.com/archives/articles/2004/7/27/110928.shtml

- "Cuba – The Republic of Cuba | history – geography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "26th of July Movement | Cuban history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Schmid, Alex; Jongman; Albert (1988). Political Terrorism: A new guide to actors, authors, concepts, data bases, theories and literature. Amsterdam, New York, North-Holland, New Brunswick: Transaction Books. p. 528.

- "La Fuerza Aérea de Cuba contra la guerrilla de Fidel Castro • Rubén Urribarres". Aviación Cubana • Rubén Urribarres. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- DeFronzo, James. Revolutions and Revolutionary Movements. (University of Connecticut. 2007) pp. 207–08

- Suddath, Claire (15 April 2009). "U.S.-Cuba Relations". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 26th of July Movement. |