1972 in the Vietnam War

1972 in the Vietnam War saw foreign involvement in South Vietnam slowly declining. Two allies, New Zealand and Thailand, which had each contributed military contingents, left South Vietnam this year. The United States continued to participate in combat, primarily with air power to assist the South Vietnamese army, while negotiators in Paris tried to hammer out a peace agreement and withdrawal strategy for the United States. One American operation that was declassified years after the war was Operation Thunderhead, a secret mission that attempted to rescue POWs.

| 1972 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

South Vietnam: 1,048,000 | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 641 killed [1] South Vietnam: 39,587 Killed[2] | 120.000 - 160.000 killed | ||

January

- 1 January

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam numbered 133,200, a reduction from more than 500,000 in 1968.[3]

- 10 January

The Cambodian Khmer National Army withdrew from the town of Ponhea Kraek (Krek) near the Fishhook abandoning the last remaining road link between Cambodia and South Vietnam. Further south in the Parrot's Beak the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)) began Operation Prek Ta against the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in that area of Cambodia. The objective of the offensive was to disrupt the preparations of the North Vietnamese for an anticipated offensive on Tết, 15 February.[4]

- 12 January

Le Duc Tho, Politburo member and secret negotiator for North Vietnam in the Paris peace talks, cabled the head of Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) in South Vietnam that "we and the enemy are preparing for a ferocious confrontation ... during the upcoming spring and summer." In addition to supporting the PAVN troops in South Vietnam, Tho instructed COSVN to devote attention to attacking the pacification program and to the political struggle in the cities of South Vietnam.[5]

- 16 January

Leaders of 46 Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish organizations met in Kansas City and asked for the withdrawal of American military personnel from South Vietnam and a cut-off in aid to the South Vietnamese government.[6]

- 20 January

The head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), General Creighton Abrams cabled Washington that "the enemy [North Vietnam] is preparing and positioning his forces for a major offensive.... There is no doubt this is to be a major campaign." Abrams requested additional authority to use U.S. American air power to mount an effective defense.[7]

- 25 January

President Richard Nixon revealed that National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger had been meeting secretly with North Vietnam representatives for more than 2 years. He also revealed the U.S. peace plan that had been proposed to Hanoi. Nixon proposed that, within six months of an agreement, all U.S. military be withdrawn from South Vietnam, Prisoners of War exchanged, an internationally supervised cease fire implemented, and a presidential election held in South Vietnam. Nixon did not demand the withdrawal of North Vietnamese military forces from South Vietnam.[8]

- 31 January

North Vietnam criticized the U.S. for making public the details of secret peace talks. North Vietnam introduced its peace plan which demanded the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of U.S. military personnel from South Vietnam and the resignation of the Thieu government.[9]

February

- 4 February

President Nixon approved additional authority to General Abrams in South Vietnam to use American power to counter the anticipated North Vietnamese offensive. Specifically, the President acknowledged the growing threat from North Vietnamese surface-to-air missiles (SAM) and authorized the United States Air Force (USAF) to strike against SAM sites in the southern part of North Vietnam and neighboring Laos.[10]

The last of Thailand's 12,000 troops in South Vietnam depart to return home.[11]

- 5 February

President Nixon ordered the draw down of USAF assets halted and the reassignment (Operation Bullet Shot) of 150 B-52 heavy bombers to Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield in Thailand in anticipation of the PAVN offensive in South Vietnam.[12]

- 11 February

G. McMurtrie Godley, U.S. Ambassador to Laos, responded negatively to a proposal by the White House, Defense Department, State Department and CIA that Laotian and Thai troops and American CIA operatives be withdrawn from Long Tieng, the headquarters of Laotian resistance to the communist Pathet Lao and PAVN. Godley argued that withdrawing from Long Tieng would plunge the United States into "an abyss" and be "a dramatic military setback and political disequilibrium at the time of the President's visit to Peking.[13]

- 12 February

Washington responded to Ambassador Godley in Laos concerning his objection to the proposed withdrawal of Lao and Thai forces and American CIA operatives from Long Tieng. Washington conceded that it was "not in position to give you detailed tactical instructions from this distance." The Department of Defense maintained that Godley should be ordered to "thin out" the forces defending Long Tieng. The State Department, CIA, and White House disagreed and left the proposed thinning out to Godley's discretion.[14] Godley chose to defend Long Tieng and the town was held for another three years until the final Communist victory in Laos.

- 13 February

On this day and the five previous days the U.S. conducted the heaviest U.S. bombing raids of the war to date. The targets were PAVN and Viet Cong (VC) bases and infiltration routes into South Vietnam. The bombing was aimed at disrupting PAVN/VC preparations for the anticipated Tết offensive.[15]

- 15 February

The Tết holiday in Vietnam. The anticipated Tết offensive by the PAVN/VC did not occur.

- 16 February

Three U.S. warplanes were shot down over North Vietnam in raids to destroy artillery positions.[16]

- 21 February

Nixon arrived in Beijing, China and met with Mao Zedong in the first direct face to face meeting between a Chinese Communist leader and an American President. North Vietnam feared that the Americans and Chinese would come up with a deal disadvantageous to North Vietnam.[17] With the relationship of the United States improving with both the Soviet Union and China the Vietnam War "began to seem an irrelevant, troublesome historical leftover that might endanger the new relationships."[18]

- 29 February

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) completed the withdrawal of its Marine brigade from South Vietnam. Two Republic of Korea Army divisions totaling 36,000 men remained in South Vietnam. The United States financed the South Korean military force.[19]

March

- 7 March

U.S. bombing of anti-aircraft installations extended up to 120 miles (190 km) north of the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The 86 air raids carried out in North Vietnam so far in 1972 equaled the number of air raids against North Vietnam during all of 1971.[20]

- 10 March

Prime Minister Lon Nol declared President of Cambodia.

The U.S. 101st Airborne Division left South Vietnam, the last U.S. ground combat division to be withdrawn from South Vietnam.[21]

- 21 March

The Khmer Rouge bombarded the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh with artillery, killing more than 100 civilians. This was the heaviest attack on Phnom Penh since the Cambodian Civil War began in 1970.[22]

- 23 March

The United States boycotted peace negotiations in Paris with the North Vietnamese, citing the failure of North Vietnam to negotiate seriously.[23]

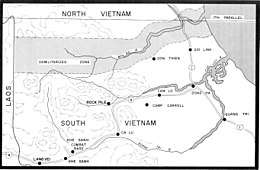

- 30 March

The long anticipated offensive by the PAVN/VC began. Called the Nguyễn Huệ Offensive or Chiến dịch Xuân hè 1972 in Vietnamese and the Easter Offensive in English, three PAVN divisions (30,000–40,000 men) with support from tanks and artillery crossed the DMZ or came from Laos to the west to attack the ARVN 3rd Division. Although a North Vietnamese offensive had been expected, the invasion across the DMZ was a surprise and the ARVN was ill-prepared. Several small firebases were overrun within hours.[24]

North Vietnam's military objectives in launching what would be a three-pronged offensive were the capture of the cities of Quang Tri in the northern part of South Vietnam, Kontum in the Central Highlands and An Loc in the south.[23]

April

- 2 April

ARVN forces numbering about 1,500 soldiers at Camp Carroll, a former United States Marine Corps base a few miles south of the DMZ, surrendered to the PAVN. Camp Carroll was important to South Vietnam because of its M107 175 mm artillery with a range of up to 20 miles (32 km). The capture of Camp Carroll gave the PAVN control of western Quảng Trị Province.[25]

With the city of Dong Ha near the DMZ threatened, Nixon authorized U.S. naval vessels offshore to strike at the PAVN with warplanes and naval gunfire.[23]

- 4 April

Nixon authorized increased bombing of PAVN troops in South Vietnam and B-52 strikes against North Vietnam. He said, "These bastards have never been bombed like they're going to be bombed this time."[23]

- 4 April

The PAVN attacked South Vietnamese positions in northern Binh Dinh province from their stronghold in the An Lao Valley. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces had contested the An Lao valley with the PAVN 3rd Division since Operation Masher in January 1966. PAVN/VC forces overran many ARVN positions.[26]

- 4–7 April

The second prong of the Easter Offensive was the movement across the border from Cambodia of the VC 5th Division and an attack on 4,000 ARVN defenders at the Battle of Loc Ninh. Lộc Ninh was a small district town in Bình Long Province, approximately 75 miles (121 km) north of Saigon. Nearly all of the ARVN defenders were killed or surrendered.[27]

- 7 April

Proceeding southward from the Lộc Ninh, PAVN/VC soldiers succeeded in surrounding the city of An Lộc, the capital of Bình Long Province and the objective of the southern prong of the Easter Offensive. The defenders of An Lộc would henceforth be supplied and reinforced by air.[28]

- 9 April

In Washington, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger warned Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin that the U.S. might take "drastic measures to end the [Vietnam] war once and for all."[29]

- 10 April

For the first time since November 1968, U.S. B-52s bombed North Vietnam in Operation Freedom Train. Their priority targets were SAM sites. The U.S. called the SAM sites "the most sophisticated air defenses in the history of air warfare.[30]

- 13 April – July 20

After several days of artillery strikes, the PAVN attacked An Lộc with tanks and infantry. They were halted at the city outskirts by ARVN defenders and heavy air attacks by the United States. The Battle of An Lộc became a siege that lasted for 66 days and culminated in a victory for South Vietnam. North Vietnam devoted 35,000 soldiers to the battle and siege. The victory at An Lộc halted the PAVN advance towards Saigon.[31]

- 15–17 April

The U.S. carried out heavy B-52 and fighter bomber strikes against Hanoi and Haiphong in Operation Freedom Porch. Nixon said, "we really left them our calling card this weekend." [32]

- 15–20 April

Anti-war demonstrators protested the bombing of North Vietnam throughout the United States. Hundreds of protesters were arrested.[33]

- 19 April

Several Vietnam People's Air Force (VPAF) MiG-17F fighter-bombers attacked United States Navy warships in the Battle of Đồng Hới. This was the first air attack on U.S. warships of the Vietnam War. One US destroyer was damaged. The U.S. navy sunk several motor torpedo boats and shot down several VPAF planes and also engaged shore batteries in North Vietnam.[34]

- 20 April

President Nixon announced that American troops would be reduced in numbers in South Vietnam from 69,000 on this date to 49,000 by 1 July. Many of those being withdrawn from South Vietnam went to Thailand to prosecute the air war from there. USAF strength in Thailand increased from 32,000 to 45,000. In addition, four additional aircraft carriers were stationed off the coast of Vietnam and the number of B-52s stationed in Thailand and Guam was increased from 50 to 200.[35]

- 21–25 April

Secretary of State Kissinger visited Moscow and met with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to prepare for an upcoming summit meeting between Nixon and Brezhnev. Nixon instructed Kissinger that his top priority was to get Soviet cooperation in seeking an agreement to end hostilities in South Vietnam. Brezhnev said he would use Soviet influence but he could not dictate to North Vietnam.[36]

- 22 April

100,000 people in various cities around the United States protest increased bombing by the US in Vietnam.[37]

- 23–24 April

After preliminary encounters, the third prong of the Easter Offensive began in the Central Highlands. The PAVN 2nd Division supported by tanks attacked the ARVN 47th Regiment, 22nd Division at Tân Cảnh Base Camp. By nightfall on 24 April, the PAVN had overrun Tan Canh and nearby Dak To II Base Camp and the 22nd Division had disintegrated.[38]

- 27 April

The United States Joint Chiefs of Staff assessed the performance of South Vietnamese armed forces thus far in the Easter offensive as "encouraging."[39]

- 29 April - 2 May

Approximately 2,000 South Vietnamese civilians are killed by indiscriminate PAVN artillery fire as they fled Quảng Trị along Highway 1.[40]

May

- 1 May

The city of Quảng Trị was captured by the PAVN, the only provincial capital to fall to them during the Easter Offensive.[41]

The preceding week saw South Vietnamese casualties, especially near Quảng Trị, reach their highest level of the entire Vietnam War. The ARVN 3rd and 22nd Divisions had disintegrated.[42]

- 8 May

Nixon withdrew his demand for a withdrawal of all North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam as a precondition for a peace agreement. Nixon proposed that all US POWs be released and an internationally supervised cease fire take place. The U.S. would cease bombing and withdraw from South Vietnam within six months after those conditions were met.[43]

Nixon also announced Operation Pocket Money, the mining of Haiphong and other North Vietnamese harbors, calculating correcting that he could take such a step without endangering the U.S.'s improving relationships with China and the Soviet Union.[44] Nixon's action inspired an outbreak of anti-Vietnam War protests around the U.S. with 1,800 arrests of protesters reported.[45]

- 14 May – 9 June

In one of the largest and most intense battles of the Easter Offensive, PAVN forces assaulted the city of Kontum and the nearby South Vietnamese base in the Battle of Kontum. Intensive U.S. airstrikes helped the ARVN fend off the PAVN and retain control of the city and nearby area although fighting in the area would continue.[46]

- 17 May

Operation Enhance began with the objective of replacing material and equipment expended or lost by South Vietnam during the Eastern Offensive. From May to October under Operation Enhance, the U.S. provided the South Vietnamese armed forces with artillery and anti-tank weapons, 69 helicopters, 55 jet fighters, 100 other aircraft and 7 patrol boats.[47]

June

- 3–12 June

Operation Thunderhead was a secret combat mission conducted by U.S. Navy SEAL Team One and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT)-11 in 1972. The mission was conducted off the coast of North Vietnam to rescue two U.S. airmen said to be escaping from a prisoner of war prison in Hanoi.[48]

- 9 June

John Paul Vann died in a helicopter crash in South Vietnam. Vann, a retired U.S. army Colonel and head of CORDS for the Central Highlands, had directed the defense of Kontum. During his years in Vietnam Vann had acquired much influence and fame and his funeral in Washington was attended by a who's who of U.S. civilian and military leaders.[49]

- 20 June

Responding to a U.S. request for a resumption of secret negotiations, North Vietnam. responded that "clothed by its goodwill, [it] agrees to private meetings." The meetings between Kissinger and Le Duc Tho would begin on 19 July.[50]

- 28 June – 16 September

The Second Battle of Quảng Trị (Vietnamese: Thành cổ Quảng Trị) began on June 28 and lasted 81 days until September 16, 1972, when the ARVN defeated the PAVN and recaptured most of the province.

- 30 June

General Frederick C. Weyand assumes command of MACV from General Abrams who is promoted to Chief of Staff of the United States Army.

August

- 5–11 August

Task Force Gimlet, Delta Company, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry undertook the last patrol by American troops in the Vietnam War to seek out PAVN/VC forces shooting rockets at the city of Da Nang. Two U.S. soldiers were wounded by booby traps. The unit was relieved by ARVN soldiers. Task Force Gimlet departed Vietnam on 11 August.[51]

- 31 August

U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Ellsworth Bunker said to President Nixon that the South Vietnamese "fear they are not yet well enough organized to compete politically with such a tough, disciplined organization", e.g. North Vietnam.[52]

September

- 1 September

Admiral Noel Gayler becomes Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC) replacing Admiral John S. McCain Jr..

- 13 September

South Vietnamese Marines recaptured Quảng Trị from the PAVN. Quảng Trị had been the only provincial capital to fall to the North Vietnamese in the Easter offensive.[53]

- 14 September

North Vietnamese negotiators in Paris hinted for the first time that they could accept a peace agreement with the United States that did not require the ouster of South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu.[54]

- 26 September

North Vietnamese negotiators in Paris proposed that a "Provisional Government of National Concord" be formed in South Vietnam to organize elections leading to the union of South and North Vietnam.[54]

October

- 8 October

In Paris, Le Duc Tho gave Kissinger documents outlining the North Vietnamese proposal for a peace agreement in Vietnam. The proposal dropped demands for the ouster of President Thiệu and called for the withdrawal of all American troops, the release of all American prisoners of war and a cease fire "in place" which would allow PAVN soldiers in South Vietnam to remain there. A tentative text was agreed upon by both sides.[55]

- 12 October

Kissinger met with Nixon in Washington to explain the draft peace agreement with North Vietnam. Nixon approved the agreement subject to the agreement of President Thiệu.[43]

- 20 October

Operation Enhance Plus began with the objective of providing additional military equipment and support to South Vietnam. Over the next two months the U.S. gave South Vietnam 234 jet fighter planes, 32 transport planes, 277 helicopters, 72 tanks, 117 armored personnel carriers, artillery and 1,726 trucks. The cost of the equipment was more than $750 million ($5.7 billion in 2015 dollars). Moreover, most of the U.S. supplied equipment of two departing South Korean divisions (approximately 38,000 men) was also given to South Vietnam. In addition, the U.S. transferred title of its military bases and all the equipment on the bases to South Vietnam.[56]

- 22 October

After meeting with Kissinger and despite a letter of support from Nixon, President Thiệu said he would never sign the draft peace agreement with North Vietnam. He demanded that all PAVN soldiers be required to leave South Vietnam.[43]

Kissinger in Saigon cabled Nixon in Washington, "While we have a moral case for bombing North Vietnam when it does not accept our proposals, it seems to be really stretching the point to bomb North Vietnam when it has accepted our proposals and South Vietnam has not."[57]

- 25 October

North Vietnam broadcast publicly the terms of the draft peace agreement and accused the United States of negotiating in bad faith.[43]

- 26 October

In Washington, despite the opposition of South Vietnam to the draft peace agreement and the charges by North Vietnam that the U.S. was negotiating in bad faith, Kissinger declared "peace was at hand" in Vietnam.[43]

- 31 October

One of the final American special forces operations of the war takes place in an intelligence-gathering mission near Cửa Việt Naval Base, Navy SEAL petty officer Michael E. Thornton saves the life of his commanding officer, Lieutenant Thomas R. Norris; he would later be awarded the Medal of Honor, the latest action in the war for which it was awarded. There were only a dozen Navy SEALs still in Vietnam at the time of the mission.

November

- 7 November

Nixon won reelection with 60.7 percent of the vote.[58]

- 14 November

In an attempt to overcome President Thiệu's objection to the draft peace agreement, Nixon wrote him that "You have my absolute assurance that if Hanoi fails to abide by the terms of this agreement, it is my intention to take swift and severe retaliatory action."

- 20 November

Kissinger returned to Paris to meet with Le Duc Tho. Tho accused Kissinger of deception. Kissinger introduced Thiệu's objections to the draft peace agreement. Both North Vietnam and South Vietnam were intransigent, the North Vietnamese demanding the agreement be signed as agreed with the United States, South Vietnam demanding changes.[59]

- 25 November

Anticipating that the peace agreement would require release of all political prisoners, the government of South Vietnam began charging people detained for political reasons with petty crimes, thus ensuring their continued incarceration. Amnesty International estimated that South Vietnam had imprisoned 200,000 people for political reasons, and would release only 5,000 after the peace agreement came into effect.[60]

December

- 4 December

Kissinger returned to Paris for further meetings with Le Duc Tho. The negotiations went nowhere and Kissinger returned to Washington on 13 December.[61]

- 12 December

President Thiệu announced that he still opposed the "false peace" in the draft peace agreement.[62]

- 14 December

Nixon met Kissinger and Presidential military aide General Alexander Haig in Washington and the three of them agreed on an intensified bombing campaign against North Vietnam to, in the words of Haig, "strike hard ... and keep on striking until the enemy's will was broken." The weapon of choice would be the B-52, which had never been used before to strike targets in the vicinity of Hanoi and the city of Haiphong.[63]

All members of the New Zealand armed forces were withdrawn from South Vietnam.[64]

- 16 December

At a press conference, speaking of the negotiations with North Vietnam Kissinger said that "the United States will not be blackmailed into an agreement." Kissinger also warned South Vietnam that "no other party will have a veto over our actions."[65]

- 17 December

American warplanes dropped mines off the coast of North Vietnam to prevent ship travel to and from the country.[66]

- 18 December

Operation Linebacker II began. Better known as the "Christmas bombings", 129 B-52s and smaller tactical aircraft struck at targets in North Vietnam, including around the city of Hanoi. North Vietnam shot down three B-52s.[67]

- 19 December

Military adviser Alexander Haig met with Thiệu in Saigon to deliver a letter from Nixon. Nixon said it was his "irrevocable intention" to achieve a peace agreement with North Vietnam, preferably with the cooperation of South Vietnam, "but, if necessary, alone." He pledged continue military support to South Vietnam if Hanoi violated the agreement. Haig told Thiệu, "Under no circumstances will President Nixon accept a veto from Saigon in regard to a peace agreement."[68]

- 20 December

North Vietnamese negotiator Xuan Thuy responded to Kissinger's remarks of 16 December. He criticized the U.S. for attempting to introduce changes to the draft peace agreement of October.[69]

Thiệu kept Haig waiting for five hours before seeing him. He attempted to persuade Haig that the U.S. should require the withdrawal of all PAVN soldiers from South Vietnam in any peace agreement. Haig suggested to Nixon that if a peace agreement was not reached the U.S. could consider a unilateral disengagement from South Vietnam in exchange for the return of American POWs by North Vietnam.[70]

North Vietnam shot down six B-52s, but depleted their supply of SAMs.[71]

- 21 December

Fearing additional losses, the U.S. deployed only 30 B-52s to bomb mostly around Hanoi and Haiphong. Nevertheless, four B-52s were hit by missiles. B-52 crew members complained that the flight patterns assigned to them increased their risk. Flight patterns were changed for subsequent days.[72]

- 22 December

Nixon offered to suspend the U.S. bombing north of the 20th parallel on 31 December if Hanoi agreed to a 3 January meeting in Paris.[73]

- 23 December

Opposition to the bombing was extensive among American politicians. In the Senate 45 Senators responding to a poll opposed the bombing as compared to 19 who supported it.[74]

- 26 December

After a Christmas truce, the U.S. conducted the largest B-52 raid of the war utilizing 120 B-52s. The U.S. lost 2 airplanes. 215 civilians were killed by bombs dropped on a heavily populated area of Hanoi. North Vietnam proposed a resumption of peace talks on January 8.[75]

- 29 December

The last bombs of Operation Linebacker II fell near Hanoi, although the U.S. continued light bombing south of the 20th parallel. Of 200 B-52s engaged in the operation, the U.S. said that 15 were shot down as well as 11 other aircraft, while Hanoi claimed that 34 B-52s had been shot down. 61 B-52 crewmen were killed, captured, or missing. Prior to Linebacker II, during seven years of bombing, only one B-52 had been shot down. Destruction of North Vietnam's military and industrial capacity was substantial. North Vietnam said that 1,623 civilians had been killed in Hanoi and Haiphong although most civilians had been evacuated from the cities before the bombing.[76]

Due to the Operation Linebacker II bombings, 80 percent of North Vietnam's electrical power production capability had been eliminated.

Nixon warned North Vietnam that the bombing would resume if the peace talks collapsed again. North Vietnam declared victory and claimed that heavy losses of American aircraft was the motive behind the bombing halt. General Maxwell Taylor, former Ambassador to South Vietnam, said terminating America's commitment to South Vietnam even without a peace agreement should be considered by the President.[77]

- 31 December

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam numbered 24,200.[78]

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs - 1972 | Military costs in 2020 US$ | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,048,000 | 39,587 | ||||||

| 24,000 | 641 | [1] | |||||

| 36,790 | [79] | ||||||

| 40 | |||||||

60,000 served 521 KIA |

|||||||

| 50 | |||||||

| 50 | |||||||

Notes

- References

- United States 2010

- Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965–1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- Lewy, Guenter, (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 147

- Deac, Wilfed P. (1996), "Losing Ground to the Khmer Rouge", Vietnam Magazine, Dec 1996, http://www.historynet.com/losing-ground-to-the-khmer-rouge.htm, accessed 9 Jun 2015

- (FRUS) Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume VIII, Vietnam, January–October 1972, Document 1, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d1#fn3, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- Summers, Jr., Harry G. (1985), Vietnam War Almanac, Oxford: Facts on File Publications, p. 55

- FRUS, document 1

- "Address to the Nation on Plan for Peace in Vietnam", Miller Center. http://millercenter.org/president/nixon/speeches/speech-3879 Archived 2015-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- "North Vietnam presents 9 Point Peace Proposal," http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/north-vietnam-presents-nine-point-peace-proposal, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- FRUS, document 15, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d15, accessed 8 June 2015

- Bowman, John S. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Pharos Books,p. 298

- Tucker, Spencer, C. (1998), The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, Vol. 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 141

- FRUS, document 21, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d21, accessed 10 Jun 2015

- FRUS, document 22, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d22, accessed 10 Jun 2015

- Butterfield, p. 300

- Bowman, p. 300

- Bowman, pp. 300–301

- Isaacs, Arnold R. (1983), Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 28

- Bowman, p. 301; Summers, Jr., p. 55

- Bowman, p. 301

- Daugherty, Leo (2012), The Vietnam War Day by Day, New York: Chartwell Books, p. 181

- Bowman, p. 302

- "The History Place--Vietnam War 1969-1972", http://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/vietnam/index-1969.html, accessed 16 Jun 2015

- Clark, p. 481

- Kutler, Stanley I. (1996), Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 185–186

- Andrade, pp. 252–259

- Andrade, Dale (1995), Trial by Fire: The 1972 Easter Offensive, America's Last Vietnam Battle, New York: Hoppocrene Books, p. 398–420

- Andrade, pp. 423–424

- Prados, John (1995), The Hidden History of the Vietnam War, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, p. 265

- Bowman, p. 305

- Willibanks, James H. (1993), Thiet Giap! The Battle of An Loc April 1972,Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, p. 13 -25-32

- Prados, p. 266

- Summers, p. 56

- Bowman, pp. 306–307

- Isaac, Arnold R. (1983), Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 19

- Asselin, Pierre (2002), A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 39–42

- Bowman, p. 307

- Andrade, pp. 265–284

- Webb, William J. and Poole, Walter S. (2007), The Joint Chiefs of State and the War in Vietnam, 1971-1973, Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, p. 214. http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/history/vn71_73.pdf%5B%5D, accessed 17 Dec 2015

- Melson, Charles (1991). U.S. Marines In Vietnam: The War That Would Not End, 1971–1973. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. pp. 84–5. ISBN 978-1482384055.

- Isaacs, Arnold R. (1983), Without Honor: Defeat in South Vietnam and Cambodia, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 2

- Bowman, p. 308

- "Memoirs v Tapes: President Nixon and the December Bombings", http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/exhibits/decbomb/chapter-ii.html Archived 2018-07-12 at the Wayback Machine., accessed 23 Jun 2015

- Isaacs, p. 18

- Bowman, p. 320

- Fulghum, David and Maitland, Terrence (1984), South Vietnam on Trial, Boston: Boston Publishing Company, pp. 156–159

- Isaacs, p. 511

- Luckett & Byler 2005, p. 187

- Sheehan, Neil (1988), A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam, New York: Vintage Books, pp. 4–21

- Lipsman, Samuel and Weiss, Stephen (1985), The Vietnam Experience: The False Peace, 1972-1974, Boston: Boston Publishing Company, p.8

- Andrade, pp. 544–545

- Lipsman and Weiss, p. 46

- Isaacs, p 2

- Lipsman and Weiss, p. 10

- Lipsman and Weiss, p. 11–13

- Jacobs, pp. 48–49, 511

- Langguth, p. 613

- Langguth, A. J. (2000), Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975, New York: Touchstone Books, p. 611

- Langguth, pp. 612–613

- Lipsman and Weiss, p. 48

- "Memoirs v. Tapes: President Nixon and the December Bombings" http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/exhibits/decbomb/chapter-iv.html#title Archived 2015-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 Jun 2015

- Isaacs, p. 2

- Asselin, pp. 143–144

- Jessup 1998, p. 523

- Asselin, p. 145

- Asselin, p 145

- Asselin, pp. 145–146

- Asselin, p. 148

- Asselin, p. 146

- Asselin, pp. 148–149

- Asselin, p. 147

- Asselin, pp 149–150

- Asselin, p. 149

- Asselin, p. 153

- Asselin, p. 150

- Asselin, pp. 150–153; Isaacs p. 55

- Asselin, p 153

- "Vietnam War Timeline: 1971-1972," http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1971.aspx, accessed 7 Jun 2015

- Leepson & Hannaford 1999, p. 209

Bibliography

- Asselin, Pierre (2002), A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2751-7.

- Jessup, John E. (1998). An encyclopedic dictionary of conflict and conflict resolution, 1945-1996 (1998 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-28112-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 887

- Leepson, Marc; Hannaford, Helen (1999). Webster's New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0028627466.

- Luckett, Perry D.; Byler, Charles L. (2005). Tempered steel: the three wars of triple Air Force cross winner Jim Kasler (2005 ed.). Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-834-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 271

- Stanton, Shelby L. (2003). Vietnam order of battle (2003 ed.). Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0071-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 396

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)