İzbırak, Midyat

İzbırak (Arabic: زاز, romanized: Zaz, Syriac: ܙܰܐܙ, romanized: Zāz)[2] is a village in Mardin Province in southeastern Turkey. It is located in the district of Midyat and the historical region of Tur Abdin.

İzbırak | |

|---|---|

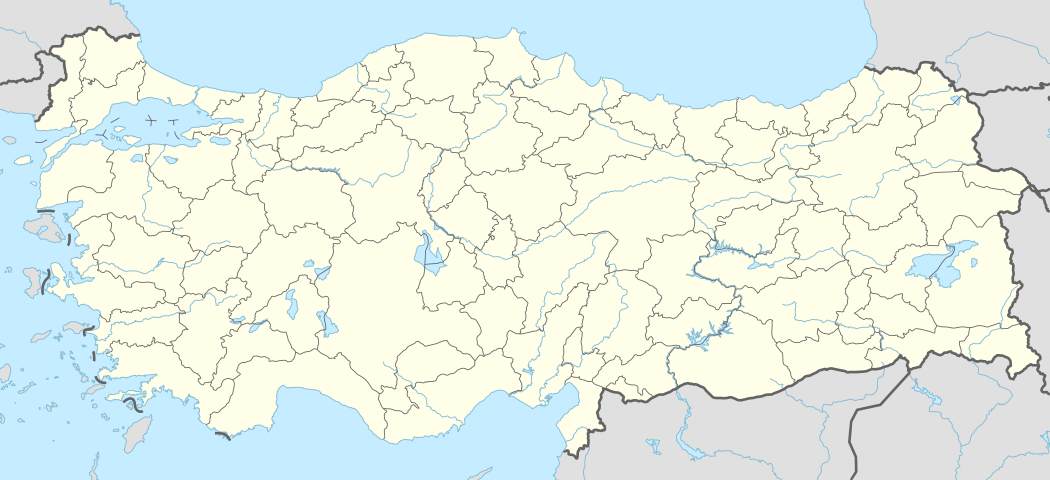

İzbırak Location in Turkey | |

| Coordinates: 37°30′47.9″N 41°32′10.0″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Mardin Province |

| District | Midyat |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 31 |

In the village, there are churches of Mor Dimet and Mort Shmuni.[3] There is also the ruins of the church of Mor Gabriel.[3]

History

Zaz is identified as the settlement of Zazabukha, where the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II made camp whilst on campaign against Nairi and received tribute from Khabkhi in 879 BC.[4] Arches on the north side of the church of Mor Dimet suggest pre-Christian buildings originally stood on the site.[5] The church of Mor Dimet was constructed by 932, from which year a funerary inscription survives.[6] A copy of the Syriac diptychs (Syriac: Sphar Ḥaye, "Book of Life") written in the village in the early 16th century was found in 1909, but was lost in the Assyrian genocide.[7]

By 1915, Zaz was exclusively inhabited by 2000 Assyrians, with 200 families, all of whom were adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[8][9] Amidst the Assyrian genocide in the First World War, the village was attacked by Kurds in August 1915, and the villagers took refuge in the church of Mor Dimet and two large houses.[9] After receiving assurances the villagers wouldn't be harmed, 365/366 Assyrians left the buildings, but were taken by the Kurds to a hill named Perbume between Zaz and Heştrek and slaughtered.[10] A survivor of the massacre at Perbume returned to Zaz and warned the villagers, who subsequently held out for a month.[11] Some survivors fled to Ayn Wardo.[12]

An Ottoman official arrived at the village and assured the villagers of their safety, only to separate the young, who were given to Kurds from neighbouring villages,[10] and split the remaining Assyrians in two groups.[9] One group was sent to Kerboran, and the other was sent to Midyat, where they were forced to collect and bury the corpses of Assyrians who had been killed in the streets of those places, as well as pick up animal faeces.[9] Those who did not die of hunger or thirst were killed once the corpses were buried.[9] Some villagers who had survived the genocide were helped to return to Zaz in 1920 by Çelebi, agha (chief) of the Heverkan clan.[9][13] A portico was added to the church of Mor Dimet in 1924.[3]

In the early 1990s, there were skirmishes between paramilitaries, the Turkish military, and Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) militants near the village as part of the Kurdish–Turkish conflict.[14] Paramilitaries and their relatives extorted 20 million Turkish lira from the villagers on 18 February 1992 on threat of killing the mukhtar Gevriye Akyol (village headman).[10] The Assyrian villagers were forced to flee to Midyat in April 1993 upon receiving death threats from paramilitaries, and they remained there in the hope the situation would improve, but again received death threats on returning to Zaz in the summer.[10] The four Kurdish families were allowed to remain,[11] whereas the Assyrians emigrated to Europe, particularly Germany and Sweden.[10]

The church of Mor Dimet was restored in the late 1990s by Assyrians in the diaspora, and a monk and nun took up residence in the church in 2001.[15][16] It was reported that Kurds from neighbouring villages had seized the Assyrians' houses and land, damaged the church by pouring sewage into it, and verbally and physically abused the monk and nun.[15]

Notable people

- Masʿūd II of Ṭur ʿAbdin (1431-1512), Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Tur Abdin[17]

References

- "İZBIRAK MAHALLESİ NÜFUSU MİDYAT MARDİN". Türkiye Nüfusu (in Turkish). Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Carlson, Thomas A. (9 December 2016). "Zāz". The Syriac Gazetteer. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 319.

- Palmer (1990), pp. 1, 29.

- Palmer (1990), pp. 29-30.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 431.

- Barsoum (2003), pp. 97-98.

- Jongerden & Verheij (2012), p. 323.

- Günaysu (2019), pp. 13-14.

- Günaysu (2019), p. 15.

- Biner (2019), p. 109.

- Çetinoğlu (2018), p. 186.

- Gaunt (2017), p. 66.

- Biner (2019), p. 115.

- Günaysu (2019), pp. 7-8.

- Güç-Işık (2014), p. 752.

- Barsoum (2003), pp. 509-510.

Bibliography

- Barsoum, Ephrem (2003). The Scattered Pearls: A History of Syriac Literature and Sciences. Translated by Matti Moosa (2nd ed.). Gorgias Press.

- Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Çetinoğlu, Sait (2018). "Genocide/ Seyfo – and how resistance became a way of life". In Hannibal Travis (ed.). The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. Translated by Abdulmesih BarAbraham. Routledge. pp. 178–191.

- Gaunt, David (2017). "Sayfo Genocide: The Culmination of an Anatolian Culture of Violence". In David Gaunt; Naures Atto; Soner O. Barthoma (eds.). Let Them Not Return: Sayfo – The Genocide against the Assyrian, Syriac and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. pp. 54–70.

- Güç-Işık, Ayşe (2014). "Süryani Cemaatinde Toplumsal Dönüşüm ve Siyasete Dâhil Olma". İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi (in Turkish). pp. 739–760.

- Günaysu, Ayşe (2019). Safety Of The Life Of Nun Verde Gökmen In The Village Zaz (Izbirak) — Midyat, Tur Abdin – And The General Social Situation Of The Assyrian Villages In The Region (PDF). Translated by Abdulmesih BarAbraham. Human Rights Association Commission Against Racism and Discrimination. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. Brill.

- Palmer, Andrew (1990). Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur Abdin. Cambridge University Press.

- Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey. 3. Pindar Press.