Zener cards

.svg.png)

Zener cards are cards used to conduct experiments for extrasensory perception (ESP) or clairvoyance. Perceptual psychologist Karl Zener (1903–1964) designed the cards in the early 1930s for experiments conducted with his colleague, parapsychologist J. B. Rhine (1895–1980).[1] The original series of experiments have been discredited and replication has proved elusive.

Overview

The Zener cards are a deck of twenty five cards, five of each symbol. The five symbols are: a hollow circle, a plus sign, three vertical wavy lines, a hollow square, and a hollow five-pointed star.[2][3] They are used to test for ESP.

In a test for ESP, the experimenter picks up a card in a shuffled pack, observes the symbol, and records the answer of the person being tested, who would guess which of the five designs is on the card. The experimenter continues until all the cards in the pack are tested.

Poor shuffling methods can make the order of cards in the deck easier to predict[4] and the cards could have been inadvertently or intentionally marked and manipulated.[5] In his experiments, J. B. Rhine first shuffled the cards by hand but later decided to use a machine for shuffling.[6]

In his book, The New Apocrypha, John Sladek expressed incredulity at the tests stating, "It's astonishing that playing cards should have been chosen for ESP research at all. They are, after all, the instrument of stage magicians and second-dealing gamblers; they can be marked and manipulated in many traditional ways. At the best of times, card-shuffling is a poor way of getting a random distribution of symbols."[5]

Rhine's experiments with Zener cards were discredited due to sensory leakage or cheating. Such as the subject being able to read the symbols from slight indentations on the back of the cards and being able to see and hear the experimenter to not facial expressions and breathing patterns.[7]

Terence Hines has written of the original experiments:

The methods the Rhines used to prevent subjects from gaining hints and clues as to the design on the cards were far from adequate. In many experiments, the cards were displayed face up, but hidden behind a small wooden shield. Several ways of obtaining information about the design on the card remain even in the presence of the shield. For instance, the subject may be able sometimes to see the design on the face-up card reflected in the agent’s glasses. Even if the agent isn’t wearing glasses it is possible to see the reflection in his cornea.[8]

Once Rhine took precautions in response to criticisms of his methods, he was unable to find any high-scoring subjects.[9]

James Alcock notes that, "Despite Rhine’s confidence that he had established the reality of extrasensory perception, he had not done so. Methodological problems with his experiments eventually came to light, and as a result parapsychologists no longer run card-guessing studies and rarely even refer to Rhine’s work."[10]

The chemist Irving Langmuir called Rhine's experiments an example of pathological science - the science of things that aren't so - and criticized its practitioners not as dishonest people but as ones that have sufficiently fooled themselves.[11]

During James Randi's TV special "Exploring Psychic Powers Live!" a psychic was tested on a deck of 250 Zener cards and was only able to predict 50 of them correctly, which is the expected result of random guessing the cards.[12]

In 2016 Massimo Polidoro tested an Italian mother and daughter that were claiming a 90% and above success rate of psychic transmission using Zener cards. Upon restricting them from seeing each other's faces and to the use of a silent writing method their success rate dropped to no better than chance. The women were cognizant of the fact that they required visual contact to achieve transmission of the symbols saying, "This kind of understanding is so natural to us, all this attention to us is also very surprising. There are no tricks, but surely we understand each other with looks. It always happens."[13]

Statistics

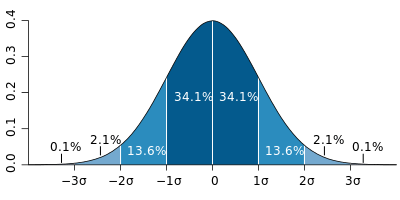

The results of many tests using Zener cards fit with a typical normal distribution.

Probability predicts these test results for a test of 25 questions with five possible answers if chance is operating:

Most people (79%) will get between 3 and 7 correct (probability is a more precise calculation).

The probability of guessing 8 or more correctly is 10.9% (in a group of 25, you can expect several scores in this range by chance).

The chances of getting 15 correct is about 1 in 90,000.

Guessing 20 out of 25 has a probability of about 1 in 5 billion.

Guessing all 25 correct has a chance of (.2) = 3.3 x 10, or about 1 in 300 quadrillion.[14]

Rather than applying Ockham's razor and accepting the null hypothesis for non-results parapsychology has invented many post-hoc constructions to explain away failure, for example:[15]

- The psi-experimenater effect - The influence of certain experimenters own psi-abilities, or lack thereof, having a positive or negative effect on the results

- The sheep-goat effect - It's observed that believers in psi-phenomena are more likely to report positive outcomes to experiments

- The psi-missing effect - Invoked when results deviate in a statistically significant way in the direction not predicted

- The decline effect - The regression to the mean over time is taken as a property of psi rather than a statistical eventuality

References

- ↑ "Zener Cards". Glossary of Skepticism & the Paranormal. About.com. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ↑ Hines, T. (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. p. 115. ISBN 9781573929790. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Matt Jarvis, Julia Russell. (2002). Key Ideas in Psychology. Nelson Thornes Ltd. p. 117

- ↑ Carroll, Bob (2006-02-17). "Zener ESP Cards". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- 1 2 Sladek, J. T. (1973). The new Apocrypha: a guide to strange science and occult beliefs. Hart-David MacGibbon. p. 174. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Pigliucci, Massimo (2010). Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science From Bunk. University of Chicago Press. pp. 80–82. ISBN 9780226667867. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Smith, J. C. (2009). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker's Toolkit. Wiley. ISBN 9781444310139. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Hines, T. (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 119–120. ISBN 9781573929790. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Christopher, Milbourne (1971). ESP, Seers & Psychics. Crowell. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Alcock`, Jim. "Back from the Future: Parapsychology and the Bem Affair". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Park, Robert L. (2002). Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud. Oxford University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780198604433. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Exploring psychic powers live [videorecording]". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ↑ Polidoro, Massimo (October 2018). "A Telepathy Investigation". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (5): 21–23. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ Shermer, Michael. "Deviations: A Skeptical Investigation of Edgar Cayce's Association for Research and Enlightenment". Skeptic.com. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Alcock, Jim E.; Burns, J. E.; Freeman, A. (2003). Psi Wars: Getting to Grips with the Paranormal. Imprint Academic. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780907845485.