ZX80

| |

| Type | Home computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | 1980 |

| Introductory price | £99.95 (£393; $504 at 2018 prices) |

| Discontinued | 1981 |

| Units shipped | 100,000[1] |

| Media | Cassette tape |

| Operating system | Sinclair BASIC |

| CPU | Z80 @ 3.25 MHz (most machines used the NEC μPD780C-1 equivalent) |

| Memory | 1 KB (16 KB max.) |

| Successor | ZX81 |

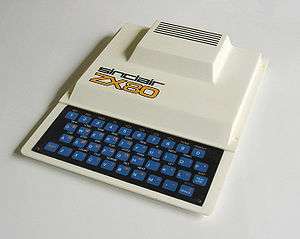

The Sinclair ZX80 is a home computer brought to market in 1980 by Science of Cambridge Ltd. (later to be better known as Sinclair Research). It is notable for being the first computer (unless one counts the MK14) available in the United Kingdom for less than a hundred pounds. It was available in kit form for £79.95, where purchasers had to assemble and solder it together, and as a ready-built version at £99.95.[2][3] The ZX80 was very popular straight away, and for some time there was a waiting list of several months for either version of the machine.

Description

Name

The ZX80 was named after the Z80 processor with the 'X' for "the mystery ingredient".[4]

Hardware

Internally, the machine was designed by Jim Westwood around a Z80 central processing unit with a clock speed of 3.25 MHz, and was equipped with 1 KB of static RAM and 4 KB of read-only memory (ROM). The ZX80 was designed around readily available TTL chips; the only proprietary technology was the firmware. The successor ZX81 used a semi-custom chip (a ULA or Uncommitted Logic Array) which combined the functions of much of the earlier hardware onto a single chip reducing the chip-count from 21 to 4. However this was mainly a cost-reduction effort;[5] the hardware functionality and system programs were very similar, with the only significant difference being the NMI-generator necessary for slow mode in the ZX81 (see ZX81 for technical details), and the 4K integer-only Sinclair BASIC upgraded to 8K floating-point-capable, with the upgraded ROM also available as upgrade for the ZX80. Both computers can be made by hobbyists using commercially available discrete logic chips or FPGAs.

Firmware

The ROM contained the Sinclair BASIC programming language, editor, and operating system. BASIC commands were not entered by typing them out but were instead selected somewhat similarly to a programmable graphing calculator - each key had a few different functions selected by both context and modes as well as with the shift key.[6]

Case

The machine was mounted in a small white plastic case, with a one-piece blue membrane keyboard on the front. There were problems with durability, reliability and overheating (despite appearances, the black stripes visible on the top rear of the case are merely cosmetic, and are not ventilation slots).

Video output

Display was over an RF connection to a household television, and simple offline program storage was possible using a cassette recorder. The video display generator of the ZX80 used minimal hardware plus a combination of software to generate a video signal. This was an idea that was popularised by Don Lancaster in his 1978 book The TV Cheap Video Cookbook and his "TV Typewriter".[7] As a result of this approach the ZX80 could only generate a picture when it was idle, i.e. waiting for a key to be pressed. When running a BASIC program, or even when pressing a key for any input, the display would, therefore, blank out momentarily while the processor was busy. This made moving graphics difficult since the program had to introduce a pause for input to display the next change in graphical output.[6] The later ZX81 improved on this somewhat because it could run in a "slow" mode while creating a video signal, or in a "fast" mode without generating a video signal (typically used for lengthy calculations). Another issue was that the main RAM was used to store the screen display, with the result that the available screen size would gradually decrease as the size of a program increased (and vice versa); with 1 KB RAM, running a 990 byte program would result in only one row of characters being visible on the screen; a full screen (32×24) would leave only 384 bytes to the programmer.

Video output was black-and-white, character-based.[6] However, the ZX80 character set included some simple block-based graphics glyphs, allowing crude graphics to be accomplished, with some effort. One advantage to using monochrome video is that different colour broadcast standards (e.g. PAL, NTSC) simply weren't an issue when the system was sold outside the UK.

Expansion

Other than the built-in cassette and video ports, the only provided means of expansion was a slot opening at the rear of the case, which exposed an expansion bus edge connector on the motherboard. The same slot bus was continued on the ZX81, and later the ZX Spectrum, which encouraged a small cottage industry of expansion devices, including memory packs, printers and even floppy drives. The original Sinclair ZX80 RAM Pack held either 1, 2 or 3 KB of static RAM and a later model held 16 KB of dynamic RAM (DRAM).

Following the ZX81's release, a ZX81 8 KB ROM was available to upgrade the ZX80 at a cost of around 20% of a real ZX81. It came with a thin keyboard overlay and a ZX81 manual. Simply taking off the top cover of the ZX80 and prying the old ROM from its socket and carefully inserting the new ROM and adding the keyboard overlay, the ZX80 would now function almost identically to the proper ZX81 – except for SLOW mode, due to the differences in hardware between the two models. The process was easily reversed to get the ZX80 back to its old self.

One of the most common modifications by hobbyist users was to move the motherboard into a larger case, with a full-size keyboard. This had the dual advantages of making the machine easier to type on, while increasing ventilation to the motherboard (reducing the likelihood of overheating).

Versions

The UK version of the machine was the standard, and only changes that were absolutely necessary to sell units in other markets were made. In fact, the only real change made in most markets involved the video output frequency (the ZX80 used an external power transformer, so differences in AC line frequency and outlet were not an issue to the machine itself). One outcome of this is that the machine had some keyboard keys and characters that were distinctly British: "Newline" was used instead of "Enter", "Rubout" instead of "Backspace" or "Delete", and the character set and keyboard included the Pound symbol.

Reception

The ZX80 was widely advertised as the first personal computer for under £100 GBP[8] (US$200.[3][6]) Kilobaud Microcomputing liked the design of the preassembled version, and said that the screen flickering during input or output was annoying but was useful as an indicator of the computer functioning correctly. It praised the documentation as excellent for novices, and noted that purchasing the computer was cheaper than taking a college class on BASIC. The magazine concluded, "The ZX-80 is a real computer and an excellent value", but only for beginners who could learn from the documentation or programmers experienced with writing Z-80 software.[9] BYTE called the ZX80 a "remarkable device". It praised the real-time, interactive BASIC syntax checking, and reported that the computer performed better on benchmarks than some competitors, including the TRS-80 Model I. The screen blanking during program execution, the small RAM size and inadequate built-in Sinclair BASIC, and the keyboard received criticism, and the review recommended against buying the kit version of the computer given the difficulty of assembly and because purchasers did not save money. BYTE concluded that "the ZX80 might be summarized as a high-performance, very low-cost, portable personal computer system ... the ZX80 is a good starting point".[6]

Sales of the ZX80 reached about 50,000, which contributed significantly to the UK leading the world in home computer ownership through the 1980s. Owing to the unsophisticated design and the tendency for the units to overheat, surviving machines in good condition are sought after and can fetch high prices by collectors.

Clones

There were also clones of the ZX80, such as the American MicroAce,[10] and from Brazil the Nova Eletrônica/Prológica NE-Z80 and the Microdigital TK82.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Hayman, Martin (July 1982). "Interview – Clive Sinclair". Practical Computing. 5 (7).

- ↑ "Advertisement for Sinclair ZX81". Practical Computing. 4: 72–73. April 1981.

- 1 2 Advertisement (January 1981). "The first personal computer for under $200". BYTE. p. 119. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ "ZX81: Small black box of computing desire". BBC News. 11 March 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Tynemouth Software: Sinclair ZX80 Repair".

- 1 2 3 4 5 McCallum, John C (January 1981). "The Sinclair Research ZX80". BYTE. pp. 94–102. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ Adamson, Ian; Richard Kennedy (1986). "A New Means To An Old End". Sinclair and the 'Sunrise' Technology. Penguin Books.

- ↑ http://rk.nvg.ntnu.no/sinclair/computers/zx80/zx80.htm

- ↑ Wszola, Stanley J. (December 1980). "The Sinclair ZX-80 Microcomputer". Kilobaud Microcomputing. pp. 168–169. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ Searls, Delmar (April 1981). "The MicroAce Computer". BYTE. pp. 46–64. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ NE Z80

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sinclair ZX80. |