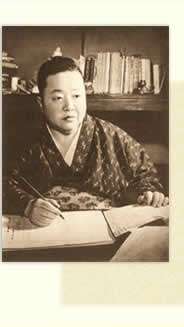

Yuriko Miyamoto

| Yuriko Miyamoto | |

|---|---|

Yuriko Miyamoto | |

| Native name | 宮本 百合子 |

| Born |

Yuriko Chūjō 13 February 1899[1] Tokyo, Japan |

| Died |

21 January 1951 (aged 51)[1] Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Genre | novels, short stories, essays, literary criticism |

| Literary movement | proletarian literature movement |

Yuriko Miyamoto (宮本 百合子 Miyamoto Yuriko, 13 February 1899 – 21 January 1951) was a Japanese novelist active during the Taishō and early Shōwa periods of Japan. Her maiden name was Chūjō (中條) Yuri.[2]

Early life

Yuriko Chūjō was born in the Koishikawa district of Tokyo (now part of Bunkyō district) to privileged parents. Her father was a Cambridge trained[1] professor of architecture at Tokyo Imperial University. She was aware at an early age of the differences between her own circumstances and those of the sharecroppers who worked her family's land, and the ensuing sense of guilt over the differences in social and economic status drew her towards socialism, and later towards the early Japanese feminist movement.

Literary career

While in her teens and a freshman in the English literature department of Japan Women's University,[1] she wrote a short story, "Mazushiki hitobito no mure" ("A Crowd of Poor People"), which was accepted for publication in the prestigious Chūō Kōron (Central Forum) literary magazine in September 1916, and which subsequently won a literary prize sponsored by the Shirakaba (White Birch) literary circle.

Leaving the university without graduating, she traveled to the United States together with her father.[1] She studied at Columbia University and met her first husband, Araki Shigeru.[1] The couple would divorced in 1924.[1] Her semi-autobiographical novel Nobuko (1924–1926) relates the failure of this marriage, her travels abroad, and finding independence as a single woman. She contemplated dedicating Nobuko to Yuasa Yoshiko, with whom she had been in an intimate relationship since 1924.[3]

Russia

In 1927, they traveled to the Soviet Union where they continued to live together for three more years.[1][3] In Moscow, they studied the Russian language and Russian literature and developed a friendship with noted movie director Sergei Eisenstein. On their return to Japan, Miyamoto became editor of the Marxist literary journal Hataraku Fujin (Working Women) and a leading figure in the proletarian literature movement. She also joined the Japan Communist Party, and, after separating from Yuasa, married its secretary-general, the communist literary critic Kenji Miyamoto, in 1932.[1]

Imprisonment

After 1932, with the government enforcement of the Peace Preservation Laws and the increasingly severe suppression of leftist political movements, Miyamoto's works were severely censored and her magazine was forbidden to publish. She was repeatedly arrested and harassed by the police, and spent more than two years in prison between 1932 and 1942. Her husband Miyamoto Kenji spent from December 1933 until August 1945 in prison.[1] During the war period, although she was mostly unable to publish, she wrote a large number of essays.

Post war

In the post-war period, she was reunited with her husband, and resumed her Communist political activities. This period was also the most prolific in her literary career.

Within a year of the end of the war she published two companion novels, The Banshū heiya (The Banshū Plain) and Fūchisō (The Weathervane Plant), both descriptive of her experiences in the months immediately following the surrender of Japan. The pair of novels received the Mainichi Cultural Prize for 1947.

Writings

The Banshū Plain is a soberly detailed account of Japan in August and September 1945. The opening chapter of The Banshū Plain depicts the day of Japan's surrender. The setting is a rural town in northern Japan, where Miyamoto, represented by the protagonist Hiroko, was living as an evacuee at the war's end. The chapter captures the sense of confusion with which many Japanese received the news of surrender—Hiroko's brother cannot explain what is happening to his children, while local farmers become drunk. Miyamoto depicts a "moral bankruptcy" which is the major theme of the novel and which is shown as the most tragic legacy of the war.

The Weathervane Plant provides a thinly fictionalized account of Miyamoto's reunion with her husband after his release from twelve years of wartime imprisonment. The couple's adjustment to living together again is shown as often painful. Despite many years of activism in the socialist women's movement, she is hurt when her husband indicates that she has become too tough and too independent after living alone during the war.

Miyamoto also published a collection of essays and literary criticism Fujin to Bungaku (Women and Literature, 1947), a collection of some of the 900 letters between her and her imprisoned husband Juninen no tegami (Letters of Twelve Years, 1950–1952), and the novels Futatsu no niwa (Two Gardens, 1948) and Dōhyō (Signposts, 1950).

Death

She died of sepsis as a complication due to acute meningitis in 1951. Her grave is at Kodaira Cemetery in Kodaira city, on the outskirts of Tokyo.

Portrayals

Yuriko, Dasvidaniya is a 2011 drama film, depicting a brief period in 1924, in which Hitomi Toi plays the title role. Directed by Sachi Hamano, the film is based on two of Yuriko's autobiographical novels, Nobuko and Futatsu no niwa, and on Hitomi Sawabe's non-fiction novel Yuriko, dasuvidaniya: Yuasa Yoshiko no seishun.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shibata Schierbeck, Sachiko; Edelstein, Marlene R. (1994). Japanese women novelists in the 20th century: 104 biographies, 1900-1993. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-87-7289-268-9. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Jaroslav Průšek and Zbigniew Słupski, eds., Dictionary of Oriental Literatures: East Asia (Charles Tuttle, 1978): 118-119.

- 1 2 Sawabe, Hitomi (2007) [1987]. "A Visit with Yuasa Yoshiko, a Dandy Scholar of Russian Literature". In McLelland, Mark; Suganuma, Katsuhiko; Welker, James. Queer Voices from Japan: First-Person Narratives from Japan's Sexual Minorities. Translated by Welker, James. Lexington Books. pp. 9, 31–40. ISBN 9780739151501. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ McLelland, Mark; Mackie, Vera, eds. (2014). Routledge Handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 9781315774879. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Buckley, Sandra. Broken Silence: Voices of Japanese Feminism. University of California Press (1997). ISBN 0-520-08514-0

- Iwabuchi, Hiroko. Miyamoto Yuriko: Kazoku, seiji, soshite feminizumu. Kanrin Shobo (1996). ISBN 4-906424-96-1

- Sawabe, Hitomi. Yuriko, dasuvidaniya: Yuasa Yoshiko no seishun. Bungei Shunju (1990). ISBN 4-16-344080-1

- Tanaka, Yukiko. To Live and To Write: Selections by Japanese women writers 1913-1938. The Seal Press (1987). ISBN 978-0-931188-43-5

- Wilson, Michiko Niikuni. ″Misreading and Un-Reading the Male Text, Finding the Female Text: Miyamoto Yuriko's Autobiographical Fiction″. U.S.–Japan Women′s Journal, English Supplement, Number 13, 1997, pp. 26–55.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yuriko Miyamoto. |

- Works by or about Yuriko Miyamoto at Internet Archive

- Works by Yuriko Miyamoto at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- listing of e-texts at Aozora Bunko