Youth unemployment in South Korea

Overall youth unemployment rate in South Korea

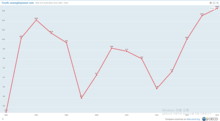

According to OECD, the youth unemployment rate (total % of youth labor force aged 15–24 year old) in Republic of Korea(ROK) is as follows: 10.2% in 2001, 8.5% in 2002, 10.05% in 2003, 10.43% in 2004, 10.15% in 2005, 9.95% in 2006, 8.79% in 2007, 9.27% in 2008, 9.84% in 2009, 9.77% in 2010, 9.61% in 2011, 8.99% in 2010, 9.34% in 2013, 10.03% in 2014, 10.52% in 2015, 10.68% in 2016.[1] More specifically, the unemployment rate (total % of youth labor force aged 25–29 year old) has been steadily rising from 6.1% in 2001 to 9.2% in 2016.[2] While, the total unemployment rate (total % of youth labor force aged 15 to 29) has been also steadily rising from 7.9% in 2001 to 9.8% in 2016.[2] In terms of youth inactivity, 7.7% is looking for jobs or attending job training programs while 3.1% are purely inactive, not working, having education nor attending job training programs.[3]

NEET

One of the youth unemployment issues in South Korea is youth inactiveness, where there are growing numbers of inactive youth, defined as the NEET(Not in Education Employment or Training).[3] The youth in South Korea prefer high education to increase and develop their employability in the labor market rather than seeking jobs, which leads them to become inactive.[3] The reaffirming factors that reduce the chance of employment include: socioeconomic status, household characteristics, and family income.[3] Since 2009, the size of youth NEET is about 20%, higher than the OECD average.[4] Although the proportion of NEET non-job seekers decreased, job seekers of NEET increased. Since 2015, the NEET unemployed remained high, overtaking NEET inactive.[4] These youth NEET are categorizable into income groups, where the highest was low income household, and the lowest was the high income household. The NEET rate of low income youth is 37.7% in 2014, while that of high income is only 9.5% in 2014.[4]

Structural Causes of Unemployment

Education

Over the past two decades, the number of students enrolled in tertiary education has quadrupled.[5] As of 2007, 80% of the college graduates were job seekers while only 30% of jobs demand highly educated workers.[6] With the recent oversupply and rapid expansion of high school and college graduates,[7] the labor market requirements mismatch that of the skills provided by the education system.[8] Coupled with poor school-business networks, insufficient employment service infrastructure, asymmetric labor market information[3] there are limited possibilities for combining study and work.[8]

Segmented Groups

The cause of unemployment is different for each segmented groups.[6] High school graduate and college dropouts have a higher rate of job separation than college graduates.[6] High job separation is due to the mismatch between jobs and workers, where workers cannot attain jobs they prefer.[6] There is also a low performance for temporary employees and seasonal workers.[6]

Other Structural Problems

Furthermore, employment regulations deter youths moving from non-regular employment to regular employment, worsening labor market duality.[8] The non-unemployed youth, especially those with lower education, do not receive assistance for job seeking.[8] The labor market rigidities including inflexible wages, high non-wage costs and employment protection also cause youth unemployment.[9] The high employment protection with low standardization of the education system, is a satisfied condition for high NEET rate.[10] Also, the public sector investment is small that regional vocational training is weak.[6] Vocational training is a responsibility of the private sector, where the private sector including large enterprises marginally invests in self vocational training.[6]

Economic Downturn

Moreover, South Korea’s economic downturns and reduced international competitiveness are one of the main problems causing youth unemployment. Due to the slowing economic growth rate of 3% since 2003, and the coefficient of employment(the number of employed workers per every one billion won of GDP) dropping by half of the level of 1990 in 2005, the employment absorptive capacity of the labor market reduced drastically.[6] In turn, this reduction makes it difficult for college graduates hard to find jobs. When demand collapse, in times of economic slumps, the young are the first to be dismissed from companies since they have no work experience.[9] The young also have are disadvantaged in entering the labor market as they compete with older employees with job experience, which makes graduates vulnerable for macroeconomic cyclical depressions, leading to high youth unemployment as well as higher precariousness within school to work transitions.[10]

Policy efforts to mitigate youth unemployment issues

History

Policy efforts to tackle youth unemployment produced a result of increased inactiveness and capped unemployment.[3] From 2004 to 2006, government measures tackled 20% of total unemployment issues, focusing on unemployment of college students and graduates.[6] Implementation was left to the colleges themselves, which made it hard for college students to approach the system voluntarily.[6]

Employment Promotion Plan for High School Graduates or Below, in 2006, provided support services to guide job seeking in order to facilitate school to work transition.[6] Also, it supported for vocational high school students, school dropouts and fostering of manual workers.[6]

Recent trends in policy

The recent trends are leaning toward the corporatist policy approach in lieu of the past market driven policy approach.[3] The corporatist approach includes: working hour reduction, public sector jobs reduction, quality improvement in small firm jobs, and expansion of public sector employment.[3] Policy efforts only accounted for .13% of South Korea's GDP, ranking it the second to the lowest among OECD countries in 2006.[3]

The newly elected president in 2017, Moon Jae-In, won the election in part by promising to reduce youth unemployment.[11] He has claimed to put top priority to expand the public sector for job creation, saying that he would create 810,000 jobs in the public sector.[11] Moon's administration promised to create 174,000 civil service positions in national security and public safety, 340,000 in social services and convert 300,000 irregular workers to fully employed workers.[11] Also, the government increased minimum wages by 16.4% at 7,530 won per-hour, aiming it to become W10,000 by 2020.[12]

However, Moon Jae-in|Moon Jae-In's administration labor policy has no influence in changing youth unemployment. Since 2017, the on-year increase of youth employed steadily decreased where 16,000 lost jobs in July and 52,000 lost jobs in October.[13] The real youth unemployment is estimated to be 21.7 percent.[12]

References

- ↑ "Total, % of youth labour force 2002-2016, Annual one highlighted country (KOR) incl. OECD, all countries". OECD.

- 1 2 "2017 Statistics on the Youth". Statistics Korea.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lee, Byoung-Hoon; Kim, Jong-Sung (2012). "A Causal Analysis of Youth Inactiveness". ekoreajournal. 52: 139~165.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Bong Joo; Noh, Hyejin (2017). "Risk factors of NEET (Not in Employment,Education or Training) in South Korea: an empirical study using panel data". Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development. doi:10.1080/02185385.2017.1289860.

- ↑ Jobs for Youth/Des emplois pour les jeunes: KOREA. OECD. Dec 2007. p. 125. ISBN 978-92-64-04079-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jeong, Insoo (2007). "The Status of Youth Unemployment in Korea and Policy Tasks". Korean Labor Institute: 76.

- ↑ An, Chong-Bum; Bosworth, Barry. Income Inequality in Korea: Trends in Korean Income Inequality (1 ed.). Harvard University Asia Center. p. 208. JSTOR j.ctt1x07vsm.5.

- 1 2 3 4 Co-operation, Organisation for Economic Development (2007). Jobs for Youth/Des Emplois pour les Jeunes: KOREA. Paris: OECD. p. 125. ISBN 9789264040793.

- 1 2 Schmid, Günther (May 2013). "Youth Unemployment in Korea: From a German" (PDF). IZA.

- 1 2 BRZINSKY-FAY, CHRISTIAN (2011). "School-to-Work Transitions in International Comparison". UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE.

- 1 2 3 "What Moon Jae-in pledged to do as president". The Korea Herald. May 10, 2017.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - 1 2 Yu-yeon, Park (November 21, 2017). "Youth Unemployment Soars Despite Gov't Efforts". ChoSunIlBo.

- ↑ Kim, Kyung-Ho (Nov 20, 2017). "Korea sees labor market polarization deepen". The Korea Herald.