Yasuo Kuniyoshi

| Yasuo Kuniyoshi | |

|---|---|

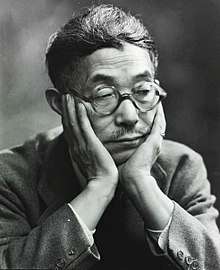

Yasuo Kuniyoshi from the Archives of American Art | |

| Born |

1889 Okayama, Japan |

| Died |

1953 (aged 63–64) New York City |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Los Angeles School of Art and Design, Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Painting, Intaglio printmaking, lithography |

| Spouse(s) | Sara Mazo[1] |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship |

Yasuo Kuniyoshi (国吉 康雄 Kuniyoshi Yasuo, 1 September 1889[2] – 14 May 1953) was an American painter, photographer and printmaker.[3]

Biography

Kuniyoshi was born in Okayama, Japan in 1889.[2] He immigrated to America in 1906, choosing not to attend military school in Japan.[4] Kuniyoshi originally intended to study English and return to Japan to work as a translator. He spent some time in Seattle, before enrolling at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design.[5] Kuniyoshi spent three years in Los Angeles, discovering his love for the arts. He then moved to New York City to pursue an art career. Kuniyoshi studied briefly at the National Academy and at the Independent School in New York City, and then studied under Kenneth Hayes Miller at the Art Students League of New York.[5] He married his first wife Katherine Schmidt,[6] who in 1919 lost her American citizenship due to her relationship with Kuniyoshi who was ineligible for American citizenship. He later taught at the Art Students League of New York in New York City and in Woodstock, New York. Nan Lurie was among his students,[7] as was Irene Krugman.[8] Around 1930, the artist built a home and studio on Ohayo Mountain Road in Woodstock. He was an active member of the artistic community there for the rest of his life.[9] One of his pupils from the League, Anne Helioff, would go on to work with him at Woodstock.[10]

Although viewed as an immigrant, Kuniyoshi was very patriotic and identified himself as an American. He never received his citizenship due to harsh immigration laws.[11] During World War II, he proclaimed his loyalty and patriotism as a propaganda artist for the United States.[12]

In 1935, Kuniyoshi was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship.[3][13] He was also an Honorary member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and President of Artists Equity.

In 1948, Kuniyoshi became the first living artist chosen to have a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[14]

In 1952, Kuniyoshi also exhibited at the Venice Biennial.[11]

In the early 1950s, Kuniyoshi became sick with cancer,[15] and ended his career as an artist with a series of black-and-white drawings using sumi-e ink.

Art

Printmaking

Kenneth Hayes Miller introduced Kuniyoshi to intaglio printmaking, and made approximately 45 prints between 1916 and 1918.[5] In 1922, he learned about zinc plate lithography and adopted the technique.[16]

Painting

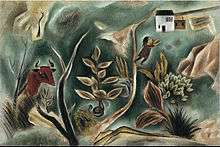

Kuniyoshi was also known for his still-life paintings of common objects, and figurative subjects like female circus performers and nudes. Throughout Kuniyoshi's career he had frequent changes in his art: methods and subject matter. In the 1920s, Kuniyoshi painted images that were more angular, somewhat Cubist style and a tilted plane that allowed him to paint the most detail for each object in his paintings. Kuniyoshi's application of Cubism's angularity can be seen in his painting titled Little Joe with Cow (1923). In these early paintings, Kuniyoshi was painting from a combination of his memory and imagination, which is a Japanese mode of thinking about painting. Instead of painting from life, like in Western painting, traditional Japanese painters typically paint the ideal image of a particular subject matter. Kuniyoshi combines this with Western painting in the way he applies the bold colors in oil on canvas;[17] in Japan, traditional painters use ink on either silk or rice paper. These early paintings are the precursors to his mature style that we see in the 1930s.[18]

In 1925, Kuniyoshi painted his, Circus Girl Resting, after a visit from Paris. He painted a provocative woman in bigger proportions similar to Strong Woman and Child. This painting was purchased and included in the Advancing American Art Exhibition by the US Department of State alongside other well known modern art artists such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Edward Hopper. Due to the aversion to modern art, it was closed down. Kuniyoshi's Circus Girl Resting was under harsh criticism by President Harry Truman because of its exotic proportions not because of its provocative nature.[19]

In the 1930s Kuniyoshi switched from painting from memory to painting from life. This change occurred after his two trips to Europe in 1925 and 1928 where he was exposed to French modern art. In 1928, Goodrich notes, Kuniyoshi spent most of his time in Paris, France with his friend Jules Pascin and it was in this later trip that Kuniyoshi realized that his art had grown stale.[20] By switching to painting from life and incorporating perspective into his paintings, he was able to breathe life back into his images; the change in his style can be seen in Daily News (1935). In this painting it appears that the woman, who is seated in a chair, occupies space within the room depicted as opposed to appearing flat as in Little Joe with Cow. The sharp angles in the cow painting are gone in his painting of the woman, but the soft line work and bold use of colors are apparent in both images.

Kuniyoshi's "Artificial Flowers and Other Things" appeared in Whitney Museum's "Second Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting," which ran from November 27, 1934, to January 10, 1935, and included the work of one other Japanese-American artist, Hideo Noda.[21]

Even in his images of women where they are full-bodied and seem to have a presence in the painting, such as the woman in Daily News, Kuniyoshi did not entirely throw out painting from memory. Goodrich points out that Kuniyoshi did not work with models for the entire painting process. Rather, the artist drew from the model in the early stages of a painting but eventually stopped using her after about a week, or so, and then would continue on from his memory, making adjustments as he saw fit.[22] This desire to paint the ideal perfection of a subject was favored in Japanese art, whereas in Western traditions the painting is typically informed by the real object throughout the entire painting process.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Yasuo Kuniyoshi papers, 1906-2013". ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART.

- 1 2 "Biographical Material". Archives of American Art. 1951. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 Fielding, Mantle (1983). "Kuniyoshi, Yasuo". In Glenn B. Opitz. Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers. Apollo. p. 536. ISBN 0-938290-02-9.

- ↑ Tatham (2006), p.99

- 1 2 3 Tatham (2006), p.100

- ↑ Asian American art, a history 1850-1970. Chang, Gordon H., Johnson, Mark Dean, 1953-, Karlstrom, Paul J., Spain, Sharon. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. 2008. ISBN 0804757526. OCLC 184925464.

- ↑ Ryley, Robert M. "Kenneth Fearing's Life". Modern American Poetry. Retrieved 2014-11-01.

- ↑ Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (19 December 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63882-5.

- ↑ Bloodgood, Josephine, At Woodstock, Kuniyoshi (Woodstock, NY: Woodstock Artists Association, 2003), pp.10-29.

- ↑ "Anne Helioff – Artist, Fine Art Prices, Auction Records for Anne Helioff". Askart.com. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- 1 2 Kantrowitz, Jonathan (2015-04-08). "Art History News: "The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi" Smithsonian American Art Museum April 3 through Aug. 30". Art History News. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ↑ "The Anxious Art Of Japanese Painter (And 'Enemy Alien') Yasuo Kuniyoshi". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ↑ http://www.gf.org/fellows/8250-yasuo-kuniyoshi

- ↑ Catlin, Roger (May 14, 2015), "Meet the Iconic Japanese-American Artist Whose Work Hasn't Been Exhibited in Decades", Smithsonian.com

- ↑ Asian American art, a history 1850-1970. Chang, Gordon H., Johnson, Mark Dean, 1953-, Karlstrom, Paul J., Spain, Sharon. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. 2008. ISBN 0804757526. OCLC 184925464.

- ↑ Tatham (2006), p.100-102

- ↑ Wolf, Tom. Yasuo Kuniyoshi's Women. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1948. VI-VII.

- ↑ Goodall, Donald B. (1975). "Introduction". Yasuo Kuniyoshi 1889–1953: A Retrospective Exhibition. pp. 27–32.

- ↑ ""Circus Girl Resting" by Yasuo Kuniyoshi - The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi / Smithsonian American Art Museum". 2.americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ↑ Goodrich, Lloyd. Yasuo Kuniyoshi: Retrospective Exhibition March 27 to May 9, 1948. Pomegranate Artbooks, 1993. 25–26.

- ↑ Second Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. 1934. p. 8 (item # 27).

- ↑ Goodrich. Yasuo Kuniyoshi: Retrospective Exhibition March 27 to May 9, 1948. 32–34.

References

- Goodall, Donald B. (1975). "Introduction". Yasuo Kuniyoshi 1889–1953: A Retrospective Exhibition. Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin. pp. 17–42.

- Goodrich, Lloyd (1948). Yasuo Kuniyoshi: Retrospective Exhibition March 27 to May 9, 1948. New York, NY: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Tatham, David (2006). "Drawn to Stone: The Early Lithographs of Yasuo Kuniyoshi". North American prints, 1913–1947: an examination at century's end. Syracuse University Press.

- Wolf, Tom (1993). Yasuo Kuniyoshi's Women. San Francisco, CA: Pomegranate Artbooks.

Bibliography

- Goodrich, Lloyd (1969). "Introduction". A Special Loan Retrospective Exhibition of Works by Yasuo Kuniyoshi 1893–1953. Gainesville, FL: University Gallery, University of Florida.

- Riehlman, Franklin; Wolf, Tom (1983). Yasuo Kuniyoshi: artist as photographer. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Edith C. Blum Art Institute, The Bard College Center.

- Wolf, Tom (2008). "The Tip of the Iceberg: Early Asian American Artists in New York". Asian Art: A History, 1850–1970. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 83–109.

- Wang, ShiPu (2011). Becoming American: The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i.

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi 1889–1953: A Retrospective Exhibition. Austin Texas: The University of Texas at Austin. 1975.

- Becoming American?: Asian Identity Negotiated Through the Art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi By Shi-Pu Wang

External links

- "The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Smithsonian American Art Museum DC, April 2 - August 29 2015". Online Exhibition

- "Wang/Becoming American?" (PDF). University of Hawai'i Press. 2011.

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi" (Densho Encyclopedia). Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Between Two Worlds: Folk Culture, Identity, and the American Art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi" (PDF). Baruch College.

- "Yasuo Kuniyoshi papers, 1906-2013". ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yasuo Kuniyoshi. |

- Artist Teacher Organizer: Yasuo Kuniyoshi in the Archives of American Art

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi papers online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Kuniyoshi Yasuo Museum, Okayama (in Japanese)

- Conti, Andrew. "Yasuo Kuniyoshi: Between Two Worlds" at the Wayback Machine (archived October 12, 2007). In Metropolis; Japan Today, as archived by archive.org on 12 October 2007.

- Union List of Artist Names, s.v. "Kuniyoshi, Yasuo", cited 2 June 2006

- Maine Family print Phillips Collection, Washington, DC

- Thinking Ahead print Phillips Collection, Washington, DC