Yarri (Wiradjuri)

Yarri (c. 1810 – 24 July 1880) also spelled "Yarrie"[1] or "Yarry"[2] was an Australian Aboriginal man of the Wiradjuri language group who rescued 49 people from the flooded Murrumbidgee River in Gundagai on the night of 24 June 1852.

Yarri's traditional name of Coonong Denamundinna indicates he was of the Rainbow serpent pastoral property near Tumblong, Adelong N.S.W. which was also associated with the Coonong region downstream of Wagga Wagga in New South Wales. Yarri worked at Nangus station as a shepherd.[3]

Yarri, and other Aboriginal men saved as many as 49 people in the Murrumbidgee floods at Gundagai, New South Wales on 25 June 1852, which killed either 78 or perhaps 89 people, out of the town's population of 250; it is one of the largest natural disasters in Australia's history. Local Aboriginal men, Yarri, Jacky Jacky[3][4], Long Jimmy and Tommy Davis played a role in saving many Gundagai people from the 1852 floodwaters, rescuing many people using bark canoes.[5] Yarri, Jacky Jacky and Tommy Davis were honoured with bronze breastplates for their efforts, and were allowed to demand sixpences from all Gundagai residents, although Yarri was maltreated on at least one occasion after the flood.[6] Long Jimmy died not long after his rescues, possibly from the effects of being exposed to the freezing cold and wet conditions.[7] The rescue effort and reward to Tommy Davis are recorded in an old Gundagai Independent newspaper. [8]

Yarri also saved John Hargreaves in 1844, and remained a friend of the family for many years, living on their Tarrabandra farm until his death. A nulla-nulla and shield believed to belong to Yarri, was presented to the Gundagai Historical Society by John Hargreaves grandson Dallas.[9]

Yarri was also known as Yarree or Coonong Denamundinna, and is believed to have killed John Baxter on the Edward John Eyre expedition in 1841,[10] and also to have killed a young part Aboriginal woman 'Sally McLeod' near Gundagai in 1852. Warrants for Yarri/Yarree's arrest were issued by NSW Police after Brungle Aboriginal people reported him to the police over the Sally McLeod murder.[11]

Yarri's wife, known as Black Sally, died in March 1873. Following an illness[12] Yarri himself died on 24 July 1880 and is buried in the Catholic Section of the North Gundagai General Cemetery.[13]

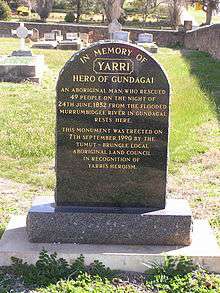

Memorials

There are several tributes to Yarri in the Gundagai area including a town memorial, sundial, marble plaque and black marble headstone.[14][15] A mural painted around the walls of the lounge bar in the Criterion Hotel in Gundagai depicts the scene.[16] Yarri Park, a recreation area below the main street in Gundagai, commemorates his feat,[17] and a sundial was erected in his honour by descendents of Fred Horsley, one of the people he saved.[13]

In 2017 a Gundagai community committee, including members of the Wiradjuri community and descendants of those saved by Yarri and Jacky Jacky, erected a bronze sculpture in Sheridan Street, Gundagai entitled "The Great Rescue of 1852" in honour of the Wiradjuri heroes.[18]

John Warner has composed a Song & Verse Cycle titled Yarri of Wiradjuri.[19]

References

- ↑ "GUNDAGAI". Cootamundra Herald (NSW : 1877 - 1954). 1937-04-30. p. 7. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ↑ "MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS". Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 - 1893). 1880-04-08. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- 1 2 Soerjohardjo, Wardiningsih (2012). "Remembering Yarrie: An Indigenous Australian and the 1852 Gundagai Flood". Public History Review. 19: 120–129 – via UTS ePress.

- ↑ "NEWS FROM THE INTERIOR. (From our Correspondents.) GUNDAGAI". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). 1852-07-05. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ↑ Mr Carr (Maroubra—Premier, Minister for the Arts, and Minister for Citizenship) (25 June 2002). "Gundagai Flood Sesquicentenary". NSW Legislative Assembly Hansard; Ministerial statement. Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 2006-01-14.

- ↑ Gundagai Times, 29 June 1879, as cited in Bodie Asimus (22 September 2003). "Yarri - a Frontier Story". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Yarri: hero of Gundagai / [A.A.C.]. Crooks, Allen (Allen A.) Published Gundagai, N.S.W. 1986 http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/10213623

- ↑ The Gundagai Independent and Pastoral, Agricultural and Mining Advocate. (NSW: 1898 – 1928.) Wed 27 March, 1912. P.4. An Old Relic. Available [online] http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/121492480?

- ↑ How an Aborigine Saved Our Australian Branch Was He Yarri?

- ↑ EYRE'S JOURNEY ACROSS THE GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT

- ↑ "SYDNEY POLICE COURT.—TUESDAY". The Empire. Sydney: National Library of Australia. 15 September 1852. p. 2. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS". The Maitland Mercury And Hunter River General Advertiser. XXXVII, (4981). New South Wales, Australia. 8 April 1880. p. 2. Retrieved 9 August 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 Bodie Asimus, NSW, Lateline ABC

- ↑ Zeppel, Heather (1999). "Hidden histories: Aboriginal cultures in NSW regional tourism brochures". CAUTHE 1999: Delighting the Senses; Proceedings from the Ninth Australian Tourism and Hospitality Research Conference.: 86–98. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Yarri Headstone". Monument Australia. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ LEODESTRAVELOZZ blog Ozzie Travel Nov 2011 Sunday, December 30, 2012 Gundagai

- ↑ Gundagai Shire Council Website Gundagai Parks

- ↑ Design, UBC Web. ""The Great Rescue of 1852" | Monument Australia". monumentaustralia.org.au. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- ↑ A Song & Verse Cycle by John Warner