Chinese alligator

| Chinese alligator | |

|---|---|

| At the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Genus: | Alligator |

| Species: | A. sinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Alligator sinensis Fauvel, 1879 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

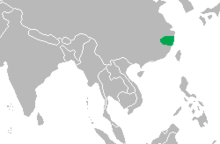

The Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis) (simplified Chinese: 扬子鳄; traditional Chinese: 揚子鱷, yáng zǐ è), also known as the Yangtze alligator, is one of two known living species of Alligator, a genus in the family Alligatoridae, and is the smaller of the two. This critically endangered species is endemic to eastern China.

Characteristics

While its appearance is very similar to the only other living member of the genus, the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), a few differences exist. Usually, this species attains an adult length of only 1.5 m (5 ft) and a mass of 36 kg (80 lb). Exceptionally large males have reached 2.1 m (7 ft) in length and 45 kg (100 lb) in weight.[3] Reports are known of alligators in China reaching 3.0 m (10 ft) in centuries past, but these are now generally considered apocryphal.[4] Unlike the American alligator, the Chinese alligator is fully armored; even its belly[3]—a feature of only a few crocodilians.

Distribution and habitat

Overall, the Chinese alligator lives in a subtropical, warm temperate region.[5] The Chinese alligator's usual habitat was in places of low-elevation and freshwater sources. This includes marshes, lakes, streams, and ponds.[6]

The alligator originally ranged through much of China. However, in the 1950s, the Chinese alligator was found only in the southern area of the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang) from Pengze to the western shore of Lake Tai (Tai Hu), in the mountainous regions of southern Anhui, and in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces. They were usually found in the lakes, streams, and marshes for a time. But in the 1970s, the species was restricted to a small part of southern Anhui and the Zhejiang provinces.[6] Then, in 1998 the biggest area the alligator lived in was a small pond along the Yangtze River surrounded by farmland, and only 11 alligators lived inside of it.[7] At this point, the alligator's geographic range had been reduced by 90%.[5] The Chinese alligator's population reduction has been mostly due to conversion of its habitat to agricultural use and pollution . A majority of their usual wetland habitats has been turned into rice paddies.[8][9] Poisoning of rats, which the alligators then eat, has also been blamed for their decline. It was also not uncommon for people to kill the alligators, because they believed they were pests, out of fear, or for their meat.[7]

Behavior

The Chinese alligator remains dormant during the winter, residing in burrows built into banks of wetlands. Once the spring comes the burrows are still used, just not as much. The alligators spend most of their time raising their body temperature in the sun. Once their body heat is high enough they become nocturnal. They can regulate their body temperature by using the water, moving into the shade when they begin to get too hot and moving into the sun if they begin to get too cold. Chinese alligators are also considered the most docile of the crocodilian order,[5] but, as with any crocodilian, they are capable of inflicting grievous bodily harm.

Reproduction

Though usually solitary, the Chinese alligator participates in bellowing choruses during the spring[5] mating season. Both sexes participate in rough unison and during the chorus the alligators remain still. The choruses last on average about 10 minutes and respond to both the chorus of both genders equally. It has been theorized that this is because the chorus is not a mating competition, simply a way for mating groups to gather together.[11] It has also been theorized, however, that these choruses do not serve any purpose. Once mating groups have gathered male Chinese alligators impregnate only one female per season.[12] Mating usually results in around 20-30 eggs. The eggs of the Chinese alligator are actually the smallest of any crocodilian. Their eggs are even smaller than other crocodilians with smaller female body sizes.[13]

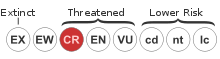

Threatened status and conservation

The Chinese alligator is a class one endangered species and listed as a CITES Appendix I species, which puts extreme restrictions on its trade and exportation throughout the world. It is currently classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.[2] To make that list, the species must have a decline of greater than 80% of the species population in a certain area of occupancy. In 1999, it was estimated by the Wildlife Conservation Society that there were only around 150 individuals left in the wild.[14] This coincided with a reversal of its decline in the wild, the population stabilizing between 1998 and 2003, followed by a slow and ongoing increase.[15]

With the help of the council of China, alligator habitat has been restored and protected. Most remaining wild individuals live in the 433 km2 (167 sq mi) Anhui Chinese Alligator Nature Reserve.[16]

The Chinese alligator is mainly endangered because of habitat pollution and reduction, as their distribution areas are turned into rice paddies. Poaching is also a concern because in traditional Chinese medicine the meat was considered to be a cure for the cold and to prevent cancer.[17] The organs are also believed to have medicinal properties.[17]

Extermination is also an issue, as farmers considered them a menace. There are many other factors that led to the endangerment of the alligator such as natural disasters, geographic separation, and hunting.[9]

In several restaurants and food centers in China's booming areas, young and immature alligators were allowed to roam free with their mouths taped shut.[18] They were subsequently killed for human consumption as, in China, alligator meat was thought to cure colds and prevent cancer.[18] In China, the organs of the Chinese alligator were sold as cures for a number of ailments.[8]

In captivity

Captive breeding programs, the first initiated in the 1970s, have been successful for the species, with over 10,000 Chinese alligators living in captivity.[19] Captive-born Chinese alligators have been reintroduced back into their native range, to boost the wild population.[20] These releases have proven successful with individuals adapting well to a life in the wild and also breeding.[21]

China

The two largest breeding centers are located in, or near, the area where Chinese alligators are still found in the wild. The largest of them, the Anhui Research Center for Chinese Alligator Reproduction (ARCCAR), was founded in 1979, and stocked with over 200 alligators collected from the wild over the following decade.[22] It also received alligator eggs collected by the area's residents or ARCCAR's own staff in the nests of wild alligators.[23] The center is located on the outskirts of the city of Xuancheng (30°54′30″N 118°46′20″E / 30.90833°N 118.77222°E), where it makes use of a series of ponds in a small valley.[24] The alligator breeding was so successful that ARCARR began to use the alligators for local meat consumption and live animals for the European pet market. The profits from these activities went to continuing funding the breeding centers.[25] ARCCAR alone has more than 10,000 Chinese alligators.[15]

The other major breeding center is the Changxing Nature Reserve and Breeding Center for Chinese Alligators (CNRBRCCA), located in Changxing County, Zhejiang Province, some 92 km east of ARCCAR (30°55′15″N 119°44′00″E / 30.92083°N 119.73333°E); it was earlier known as Yinjiabian Alligator Conservation Area (尹家边扬子鳄保护区; established 1982).[25][26] Unlike ARCCAR, where alligator eggs are collected by the center's staff for incubation in controlled condition, at Changxing they are allowed to hatch naturally.[24] According to a 2013 official report[27] quoted by Liu (2013), CNRBRCCA housed almost 4,000 alligators, including over 2,000 young ones (1–3 years old), over 1,500 juveniles (4–12 years old), and 248 adults (13+ years old).[28]

Both ARCARR and the Changxing Center position themselves as tourist attractions, where paying visitors can view alligators and learn about these reptiles.[29]

North America and Europe

Although by far the largest number of captive Chinese alligators are at centers in its native country, the species is also kept and bred at many zoos and aquariums in North America and Europe. Some individuals bred there have been returned to China for reintroduction to the wild.[20]

Among the North American zoos and aquariums keeping this species are the Bronx Zoo, Potawatomi Zoo, Toledo Zoo, Memphis Zoo, St. Louis Zoo, Philadelphia Zoo,[30] Cincinnati Zoo,[20] Santa Barbara Zoo,[31] and San Diego Zoo. In Europe, about 25 zoos and aquariums keep the species, such as the Tierpark Berlin (Germany), Wildlands Adventure Zoo Emmen (Netherlands), Pairi Daiza (Belgium), Bioparco di Roma (Italy), Barcelona Zoo (Spain), Crocodile Zoo (Denmark), Parken Zoo (Sweden), Paradise Wildlife Park (England), Prague Zoo (Czech Republic), Tallinn Zoo (Estonia), and Moscow Zoo (Russia).[32]

See also

References

- ↑ "Fossilworks: Alligatoridae". paleodb.org.

- 1 2 Crocodile Specialist Group (1996). "Alligator sinensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 1996: e.T867A13086708. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- 1 2 "Chinese alligator". Aquaticcommunity.com. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Groppi, Lauren. "Animal Diversity Web." ADW: Alligator Sinensis: INFORMATION. Animal Diversity Web, n.d. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

- 1 2 Thorbjarnarson, John; et al. (2002). "Wild populations of the Chinese alligator approach extinction". Biological Conservation. 103 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(01)00128-8.

- 1 2 Gallagher, Sean. "The Chinese Alligator, A Species On The Brink." News Watch. National Geographic, 26 Apr. 2011. Web. 23 Oct. 2013.

- 1 2 "www.flmnh.ufl.edu". www.flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- 1 2 "The Chinese Alligator: Species On The Brink". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ Iijima, Masaya; Takahashi, Keiichi; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu (2016). "The oldest record of Alligator sinensis from the Late Pliocene of Western Japan, and its biogeographic implication". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 124: 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2016.04.017.

- ↑ Wang, Xianyan; et al. (2009). "Why do Chinese alligators (Alligator sinensis) form bellowing choruses: A playback approach". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 126: 2082. doi:10.1121/1.3203667.

- ↑ Neill, W. 1971. The Last of the Ruling Reptiles: Alligators, Crocodiles, and Their Kin. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson, John; Wang, Xiaoming (2010), The Chinese Alligator: Ecology, Behavior, Conservation, and Culture, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-9348-8

- ↑ "Alligator sinensis". Arkive.org.

- 1 2 Jiang, H.X. (2010). Chinese Alligator Alligator sinensis. Pp. 5-9 in Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Third Edition, ed. by S.C. Manolis and C. Stevenson. Crocodile Specialist Group: Darwin.

- ↑ Crocodilians: Alligator sinensis. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Ten Threatened and Endangered Species Used in Traditional Medicine". Smithsonian Magazine. October 18, 2011.

- 1 2 Chang, L. T., and Olson, R.. Gilded Age, Gilded Cage. National Geographic Magazine, May 2008.

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson, John; Wang, Xiaoming (2010). The Chinese Alligator: Ecology, Behavior, Conservation, and Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-9348-8.

- 1 2 3 "Chinese Alligator". cincinnatizoo.org. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ UNDP in China (8 June 2016). The largest group of Chinese alligators released to the wild. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson & Wang 2010, pp. 175–176

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson & Wang 2010, pp. 200–202

- 1 2 Thorbjarnarson & Wang 2010, p. 195

- 1 2 Thorbjarnarson & Wang 2010, p. 205

- ↑ 尹家边扬子鳄保护区 (Yinjiabian Alligator Conservation Area)

- ↑ 从抢救保护到放归发展 浙江长兴成功繁殖扬子鳄, (From rescue and protection to reintroduction development. Changxing in Zhejiang successfully propagated Chinese Alligators) 2013-04-29 (in Chinese)

- ↑ Liu, Victor H. (2013), "Chinese Alligators: Observations at Changxing Nature Reserve & Breeding Center" (PDF), IRCF Reptiles and Amphibians, 20 (4): 172–183

- ↑ Thorbjarnarson & Wang 2010, pp. 195,198,205

- ↑ "Chinese Alligator". Saint Louis Zoo. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ↑ "Animal Management". Santa Barbara Zoo. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ↑ Zootierliste: Chinese alligator. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

Further reading

- Species Alligator sinensis at The Reptile Database

- Hu, Y.; Wu, X. B. (2010). "Multiple paternity in Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis) clutches during a reproductive season at Xuanzhou Nature Reserve". Amphibia-Reptilia. 31 (3): 419–424. doi:10.1163/156853810791769446.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alligator sinensis. |