Women's suffrage in states of the United States

Women's suffrage in states of the United States refers to women's right to vote in individual states of that country. Suffrage was established on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a Member of Congress.

The campaign to establish women's right to vote in the states was conducted simultaneously with the campaign for an amendment to the United States Constitution that would establish that right fully in all states. That campaign succeeded with the ratification of Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Background

The demand for women's suffrage began to gather strength in the 1840s, emerging from the broader movement for women's rights. The first national suffrage organizations were established in 1869 when two competing organizations were formed, each campaigning for suffrage at both the state and national levels. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was especially interested in national suffrage amendment. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, tended to work more for suffrage at the state level.[1] They merged in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[2]

Prospects for a national amendment looked dim at the turn of the century, and progress at the state level had slowed.[3] In the 1910s, however, the drive for a national amendment was revitalized, and the movement achieved a series of successes at the state level. The newly formed National Woman's Party (NWP), a militant organization led by Alice Paul, focused almost exclusively on the national amendment. The larger NAWSA, under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, also made the suffrage amendment its top priority.[4] In September 1918, President Wilson spoke before the Senate, asking for the suffrage amendment to be approved. The amendment was approved by Congress in 1919 and by the required number of states a year later.[5]

States and regions

West

On the whole, western states and territories were more favorable to women's suffrage than eastern ones. It has been suggested that western areas, faced with a shortage of women on the frontier, "sweetened the deal" in order to make themselves more attractive to women so as to encourage female immigration or that they gave the vote as a reward to those women already there. Susan Anthony said that western men were more chivalrous than their eastern brethren.[6] In 1871 Anthony and Stanton toured several western states, with special attention to the territories of Wyoming and Utah where women already had equal suffrage. Their suffragist speeches were often ridiculed or denounced by the opinion makers - the politicians, ministers, and editors. Anthony returned to the West in 1877, 1895, and 1896. By the last trip, at age 76, Anthony's views had gained popularity and respect. Activists concentrated on the single issue of suffrage and went directly to the opinion makers to educate them and to persuade them to support the goal of suffrage.[7]

By 1920 when women got the vote nationwide, Wyoming women had already been voting for half a century.

Kansas

In March 1867, the Kansas legislature decided to include two suffrage referenda in that year's November election. If approved by the voters, one would enfranchise African Americans and the other would enfranchise women. The proposal for the referendum on women's suffrage, the first in the U.S., originated with state senator Sam Wood, leader of a rebel faction of the state Republican Party. Wood had moved to Kansas to oppose the extension of slavery into that state.[8]

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) actively supported both referenda. The AERA, which advocated suffrage for both women and blacks, had been formed in 1866 by abolitionists and women's rights activists. Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell launched the AERA campaign in Kansas. In April they assisted with the formation of a state organization called the Impartial Suffrage Association, which was led by Charles L. Robinson, a former governor who was Stone's brother's brother-in-law, and Sam Wood.[9] Olympia Brown arrived in Kansas on July 1 to relieve Stone and Blackwell as leader of the AERA campaign, handling that task almost single-handedly until Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton arrived in September. The AERA could not afford to send more activists because money that had expected to support their campaign had been blocked by Wendell Phillips, a leading abolitionist. Although he supported women's rights, Phillips believed that suffrage for African American men was the key issue of the day, and he objected to mixing the issues of suffrage for blacks and women.[10]

The AERA had hoped for assistance from the Kansas Republican Party. The Republicans instead decided to support suffrage for black men only and formed an "Anti Female Suffrage Committee" to oppose those who were campaigning for women's suffrage.[11][12] By the end of summer the AERA campaign had almost collapsed under the weight of Republican hostility, and its finances were exhausted.[13]

Anthony and Stanton created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last two and a half weeks of the campaign from George Francis Train, a Democrat, a wealthy businessman and a flamboyant speaker who supported women's rights. Train, however, also openly disparaged the integrity and intelligence of African Americans, supporting women's suffrage partly in the belief that the votes of women would help contain the political power of blacks.[14] The usual procedure was for Anthony to speak first, declaring that the ability to vote rightfully belonged to both women and blacks. Train would speak next, declaring that it would be an outrage for blacks to vote but not women also.[15] The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members. This was due partly to Train's attitude toward blacks and partly to his harsh attacks on the Republican Party: he made no secret of his desire to blemish its progressive image and create splits within it. Many reformers were loyal to the national Republican Party, which had provided political leadership for the elimination of slavery and was still in the difficult process of consolidating that victory.[16]

Suffrage for women was defeated in the November election by 19,857 votes to 9,070; suffrage for blacks was defeated 19,421 to 10,483.[17] The tension created by the failed AERA campaign in Kansas contributed to the growing split in the women's suffrage movement.[18]

In 1887, suffrage for women was secured for municipal elections. A referendum for full suffrage was defeated in 1894, despite the rural syndication of the pro-suffragist The Farmer's Wife newspaper and a better-concerted, but fractured campaign. A third referendum campaign in 1911-1912 gained even greater support, with supporters delivering 100 petitions with 25,000 signatures to Topeka. The fact that Kansas had already banned saloons since 1880 had severely weakened the anti-suffrage opposition by eliminating their traditional voter base of saloon patrons. The 1911-1912 pro-suffrage proposers also conducted a less-perceivably-antagonistic campaign among male voters. The pro-suffrage side finally secured a women's suffrage amendment, and Kansas became the eighth state to allow for full suffrage for women.[19]

Wyoming

The first territorial legislature of the Wyoming Territory granted women suffrage in 1869.[20] On September 6, 1870, Louisa Ann Swain of Laramie, Wyoming became the first woman to cast a vote in a general election.[21][22] In 1890, Wyoming under Republican control was admitted to the Union as the first state that allowed women to vote, and in fact insisted it would not accept statehood without keeping suffrage.

Utah

The Mormon issue made the fight for women's suffrage in Utah unique. In 1869 the Utah Territory, controlled by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, gave women the right to vote. Sarah Young, the niece of Brigham Young, was the first woman to legally vote in the United States, due to a municipal election held on February 14, 1869 (Wyoming had recognized women's right to vote earlier that year, but had not yet held an election).[23] However, in 1887, Congress disenfranchised Utah women with the Edmunds–Tucker Act, which was designed to weaken the Mormons politically and punish them for polygamy. At the same time, however, certain activists, particularly Presbyterians and other Protestants convinced that Mormonism was a non-Christian cult that grossly mistreated women, promoted women's suffrage in Utah as an experiment, and as a way to eliminate polygamy.[24] The LDS Church officially ended its endorsement of polygamy in 1890 and in 1895 Utah adopted a constitution restoring the right of woman suffrage. Congress admitted Utah as a state with that constitution in 1896.[25]

Washington

In 1854, Washington became one of the first territories to attempt granting voting rights to women; the legislative measure was defeated by only one vote. In 1871, the Washington Women's Suffrage Association was formed, largely attributable to a crusade through Washington and Oregon led by Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Scott Duniway. The late nineteenth century saw a seesaw of bills passed by the Territorial Legislature and subsequently overturned by the Territorial Supreme Court, as the competing interests of the suffrage movement and the liquor industry (which was being damaged by the women's vote) battled over the issue. The first successful bill passed in 1883 (overturned in 1887), the next in 1888 (overturned the same year). The women's suffrage movement next hoped to secure the right to vote via voter referendum, first in 1889 (the same year Washington achieved statehood), and again in 1898, but both referendum bids were unsuccessful. A constitutional amendment finally granted women the right to vote in 1910.[26][27][28]

Colorado and Idaho

After Wyoming gained statehood, Colorado and Idaho were the next two states to give women the vote. In 1893, a referendum in Colorado made that state the second state to give women suffrage and the first state where the men voted to give women the right to vote.[29] Later, Idaho approved a constitutional amendment in 1896 with a statewide vote giving women the right to vote.

California

California's voters granted women's suffrage in 1911, when they adopted Proposition 4. Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee (October 21, 1886 – October 5, 1993) was the first Chinese American woman voter in the United States. She registered to vote on November 8, 1911 in California.[30]

Oregon, Montana, Arizona

One after another, western states granted the right of voting to their women citizens, the only opposition being presented by the liquor interests and the machine politicians. In Oregon, Abigail Scott Duniway (1834–1915) was the long-time leader, supporting the cause through speeches and her weekly newspaper The New Northwest, (1871–1887).[31] Suffrage was won in 1912 by activists who used the new initiative processes. Montana's men voted to end the discrimination against women in 1914, and together they proceeded to elect the first woman to the United States Congress in 1916, Jeannette Rankin.

Arizona became a state in 1912, but it had many conservative Southerners and its new constitution did not include women's suffrage. Activists formed the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) and launched a campaign to win the vote. Their tactics were to reach out to progressive organizations for endorsements, winning the support of influential political and civic leaders, and getting help from NAWSA for speakers and funds. AESA sent delegations to the Republican and Democratic state conventions to argue for their support. The tactics worked and the men voted for woman suffrage in the general election held on 5 November 1912.[32]

Upper Midwest

Norwegian American women, based in the rural upper Midwest, felt that the progressive politics of Norway, which included women's rights, provided a strong foundation for their demands for political equality and inclusion in the U.S. They told their kinswomen they had a cultural duty to promote women's rights, especially through the Scandinavian Woman's Suffrage Association.[33]

East

New York

Suffragists, knowing that women's suffrage could not succeed without support, put their hope in the Equal Rights Association and pushed for a campaign for universal suffrage. From April until November 1867, women furiously campaigned, distributing thousands of pamphlets and speaking in numerous locations for the cause. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton focused their attentions on New York, while Stone and Blackwell headed to Kansas, where the November election would be taking place.[34]

During the New York Constitutional Convention, held on June 4, 1867, Horace Greeley, the chairman of the committee on Suffrage and an ardent supporter of women's suffrage over the previous 20 years, betrayed the women's movement and submitted a report in favor of removal of property qualification for free black men, but against women's suffrage. New York legislators supported the report by a vote of 125 to 19.[35]

Harriot Stanton Blatch, the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, focused on New York where she succeeded in mobilizing many working-class women, even as she continued to collaborate with prominent society women. She could organize militant street protests while still working expertly in backroom politics to neutralize the opposition of Sharp Hall politicians who feared the women would vote for prohibition.[36] New York finally joined the procession in 1917 after Tammany Hall ended its opposition.

New Jersey

New Jersey, on confederation of the United States following the Revolutionary War, placed only one restriction on the general suffrage—the possession of at least £50 (about $8,700 adjusted for inflation) in cash or property.[37][38] In 1790, the law was revised to include women specifically, and in 1797 the election laws referred to a voter as "he or she".[39] Female voters became so objectionable to professional politicians, that in 1807 the law was revised to exclude them. Later, when New Jersey rewrote its constitution, the 1844 constitution limited a guaranteed right to vote to men. By 1947, all state constitutional provisions that barred women from voting had been rendered ineffective by the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920. The updated constitution of 1947, reflecting this, once again included women as eligible voters—as they had been in New Jersey in 1776.

Connecticut

The women's suffrage movement in Connecticut was pioneered by Frances Ellen Burr, a lecturer and writer who led a petition drive for suffrage in the 1860s. She had been part of the women's movement for some time, having attended the National Women's Rights Convention in Cleveland in 1853. Through her efforts, a women's suffrage bill was introduced into the state House of Representatives in 1867. It was defeated by a vote of 111 to 93.[40]

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was formed at the state's first women's suffrage convention at the Robert's Opera House in Hartford on October 28–29, 1869. The convention was organized by a group that included Burr, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The meeting was addressed by a number of luminaries, including Henry Ward Beecher, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Julia Ward Howe and William Lloyd Garrison.[41] The convention, with its heavy involvement by the influential Beecher family, did not receive the hostile reception that similar conventions had received in other places. The local press reported on the convention in a respectful way, and Stanton, Howe and Anthony were entertained by the governor and his wife at the governor's mansion.[42]

At the time of the convention, the national women's movement was in the process of splitting. One wing, associated with Stanton and Anthony, had formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The other, associated with Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, had formed the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) and would soon form the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Isabella Beecher Hooker invited both parties to the Hartford convention and tried to heal the breach between them, but was unsuccessful.[43] The Beecher family generally opposed Anthony's and Stanton's NWSA (Isabella's brother, Henry Ward Beecher, was the first president of the more moderate AWSA[44]). Isabella, however, was friendly with Anthony and Stanton and served as NWSA's vice president for Connecticut.[45]

Isabella Beecher Hooker was the leading force in the CWSA and led the suffrage movement in that state for the rest of the century.[46][40] The New England Woman Suffrage Association organized affiliated state suffrage societies in most New England states except for Connecticut.[47] The CWSA recorded a membership of 288 in 1871.[46]

In the 1870s, sisters Julia and Abby Smith, sometimes known as the "Maids of Glastonbury," engaged in a "no taxation without representation" protest. They refused to pay their local taxes because women were not allowed to vote on tax issues. The town seized their property to pay the taxes.[48]

The movement won a few victories during this period. Married women won the right to control their own property in 1877. Women won the right to vote for school officials in 1893 and on library issues in 1909. The slow pace of progress was discouraging, however, and by 1906, the CWSA was down to 50 members.[49]

In 1909, at time of a nation-wide upsurge in the women's suffrage movement, Katharine Houghton Hepburn (mother of Academy Award winning actress Katharine Hepburn) co-founded the Hartford Equal Suffrage League. In 1910, that organization merged with the CWSA, and Hepburn became its president.[50] Imbued with new energy, the CWSA sponsored a month-long automobile tour in 1911 that established a number of new local chapters. In 1914, it was the main organizer of the state's first suffrage parade, with 2000 participants. By 1917, the organization had 32,000 members.[49]

With Hepburn's support, a branch of a suffrage organization called the Congressional Union was formed in Connecticut in 1915. By 1917, it had become the state branch of the National Woman's Party (NWP), a rival to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) with which the CWSA was affiliated. Adopting the militant tactics of the NWP, fourteen Connecticut suffragists were arrested between 1917 and 1919 in Washington, D.C. for picketing the White House.[49] Distressed by the NAWSA's reluctance to condemn the harsh treatment of the protesters, Hepburn resigned her post as president of the CWSA in 1917 and joined the NWP, soon becoming a member of its national executive committee. She did not resign her CWSA membership, however, and continued to attend its board meetings.[51]

Such cooperation across rival organizational lines was not uncommon in the Connecticut women's movement. In many other states and at the national level, by contrast, the NWP and the much larger NAWSA tended to be bitter and uncooperative rivals. A representative statement of Connecticut approach was expressed Ruth McIntire Dadourian, the CWSA executive secretary, who said, "I felt that the Woman's Party was really the spearhead and then we could follow through. The more outrageous they were, the better off we were."[52]

Controlled by conservative Henry Roraback's Republican Party machine, Connecticut resisted the rapidly increasing pressure across the country to support the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which would prohibit the denial of the right to vote on the basis of sex. The state legislature, which finally met in a special session called specifically to consider the amendment, ratified it in September 1920, a month after it had already become the law of the land because a sufficient number of other states had ratified it.[49] Its work done, the CWSA dissolved in 1921.[41]

Mid-West

Illinois

In 1912, Grace Wilbur Trout, then head of the Chicago Political Equality League, was elected president of the state organization. Changing her tactics from a confrontational style of lobbying the state legislature, she turned to building the organization internally. She made sure that a local organization was started in every Senate district. She sent four lobbyists to Springfield, the state capital, to persuade one legislator at a time to support suffrage for women.

After passing the State Senate, the bill was brought up for a vote in the House on June 11, 1913. Trout and her team counted heads and went as far as to fetch needed male voters from their homes. Watching the door to the House chambers, Trout urged members in favor not to leave before the vote, while also trying to prevent "anti" lobbyists from illegally being allowed onto the House floor. The bill passed with six votes to spare, 83 to 58. On June 26, 1913, Illinois Governor Edward F. Dunne signed the bill in the presence of Trout, Booth and union labor leader Margaret Healy.

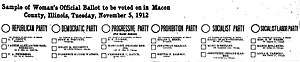

Women in Illinois could now vote for presidential electors and for all local offices not specifically named in the Illinois Constitution. However, they still could not vote for state representative, congressman or governor; and they still had to use separate ballots and ballot boxes. But by virtue of this law, Illinois had become the first state east of the Mississippi River to grant women the right to vote for President. Carrie Chapman Catt wrote,

The effect of this victory upon the nation was astounding. When the first Illinois election took place in April, (1914) the press carried the headlines that 250,000 women had voted in Chicago. Illinois, with its large electoral vote of 29, proved the turning point beyond which politicians at last got a clear view of the fact that women were gaining genuine political power.

Besides the passage of the Illinois Municipal Voting Act, 1913 was also a significant year in other facets of the women's suffrage movement. In Chicago, Ida B. Wells-Barnett founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first such organization for Negro women in Illinois. Although white women as a group were sometimes ambivalent about obtaining the franchise, African American women were almost universally in favor of gaining the vote to help end their sexual exploitation, promote their educational opportunities and protect those who were wage earners. African-American women often found themselves fighting both sexism and racism. As a result, there was an African-American Woman Suffrage Movement.

South

Southern suffragists are often left out of mainstream histories of the movement. Their work was embued with the cultural assumptions of their day.[53] Many suffragists in the South - both white and black - were predominantly clubwomen, highly educated and often from more elite families. Black women suffragists worked within their local clubs and later with the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, sometimes also becoming individual members of a suffrage association when their clubs were denied membership. Many black women educators, active in their teacher associations, would speak out also for voting rights - either for their men who were granted voting rights with the 15th Amendment - or sometimes specifying voting rights for black women too.[54] White middle-class women of the South who fought for voting rights were skilled in organizational efforts utilized in memorializing the Lost Cause[55] - either through a Ladies' Memorial Association or the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[56] In 1906 twelve delegates from states throughout the South came together in Memphis to form the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference. Laura Clay was elected president. This group broke from the NAWSA, which had turned away from its "Southern Strategy" efforts and worked instead to win suffrage at the state and local levels rather than with a federal amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Kentucky

In 1838, Kentucky passed the first statewide woman suffrage law (since New Jersey revoked theirs with their new constitution in 1807) – allowing female heads of household to vote in elections deciding on taxes and local boards for the new county "common school" system. The law exempted the cities of Louisville, Lexington and Maysville since they had already adopted a system of public schools.[57] Kentucky was crucial as a gateway to the South for women's rights activists. Lucy Stone came through Louisville in November 1853 – wearing her own version of Amelia Bloomer trousers – earned $600 with thousands packing the halls each night.[58] After the Civil War, when the 13th Amendment was ratified by 2/3 of the states (not including Kentucky) on January 1, 1866, Lexington's Main Street was filled with African Americans in a military parade, followed by Black businesspeople and several hundred children with political speeches at Lexington Fairgrounds (now the University of Kentucky). By March a Black Convention was held in Lexington to discuss equal rights for Blacks. The next year, for July 4, a barbecue organized in Lexington by Black women included speeches made by both Black and by White speakers in favor of black suffrage and ratification of the 14th Amendment. That fall, another Black Convention included a debate on how to gain full civil rights for Blacks, including the right to vote and the right to testify in court against whites.[59] From the 11th National Women's Rights Convention and a merger with former abolitionists, the American Equal Rights Association formed to lobby the new federal government and the states for full rights for all citizens. In 1867 Virginia Penny of Louisville was elected Vice-President - her first book, The Employments of Women: A Cyclopaedia of Woman's Work was recently published (1863).[60] Also in 1867, the first suffrage association in the South is in Kentucky – Glendale, with 20 members.[61] Also, first in the South, were the two suffrage associations - one in Madison County and the other in Fayette County - started in the 1870s by Mary Barr Clay who has already begun serving in both the national suffrage associations (NWSA and AWSA) as vice-president. In October 1881, the AWSA held its national convention in Louisville, Kentucky - the first such convention south of the Mason-Dixon line. At this convention, the first statewide suffrage association in Kentucky was founded, and Laura Clay was elected president. In July 1887 Mary E. Britton spoke for woman suffrage at the Colored Teachers Association meeting in Danville, Kentucky.

When the NAWSA was formed in 1890, Laura Clay became the main voice for Southern white clubwomen. She led many campaigns through the South and the West on behalf of the NAWSA while she continues to support efforts in Kentucky to proliferate city/county suffrage associations—seven of them by 1890. In February 1894 Sallie Clay Bennett (Laura's older sister) spoke on behalf of the NAWSA before the U.S. Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage emphasizing the right of black men and women to vote because all were citizens. Mrs. Bennett wrote a political treatise that was presented to Congress by Senator Lindsay and Rep McCreary on behalf of the NAWSA, "asking Congress to protect white and black women equally with black men against State denial of the right to vote for members of Congress and the Presidential electors in the States…" – writing private letters to every member of Congress and sending copies to editors of newspapers in every state.[62] Eugenia B. Farmer of Covington figured out that the charters for second-class cities in Kentucky were up for renewal and the Kentucky Equal Rights Association (KERA) lobbied successfully in the Kentucky Constitutional Convention to get the legislature to grant those municipalities the right to grant woman suffrage.[63] In March 1894 the Kentucky General Assembly granted school suffrage to women in the cities of Lexington, Covington and Newport; and, Josephine Henry succeeded in her lobbying for the state law for a Married Woman's Property Act. In 1902, because of the fear of an organized bloc of Lexington's African-American women registered to vote for school board members in the Republican Party, the Kentucky legislature revoked this partial suffrage. The Kentucky Association of Colored Women's Clubs formed in 1903 with 112 clubs, and suffrage is a part of the efforts undertaken by their clubs. The newly organized Kentucky Federation of Women's Clubs (whites only) formed and lobbied to regain school suffrage in Kentucky, finally winning it back in 1912 with an added proviso (just for women) of a "literacy" test.

In 1912 Laura Clay stepped down as president of KERA in favor of her distant cousin Madeline McDowell Breckinridge;[64] and in 1913 Clay was elected to lead a new organization, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference, founded to win the vote through state enactment. In August 1918 Laura Clay and Mrs. Harrison G. (Elizabeth Dunster) Foster, formerly a leader of suffrage in Washington, formed the Citizens Committee which formally broke with KERA - and the next year, Laura Clay finally quit working for NAWSA and turned to securing a state suffrage bill in Kentucky.[65] Presidential suffrage for women in Kentucky is signed into law on March 29, 1920.

In the early days of January 1920, National Woman's Party members Dora Lewis and Mabel Vernon travel to Kentucky to assure success, and on January 6, Kentucky became the 23rd state to ratify the 19th Amendment. On December 15, 1920, the Kentucky Equal Rights Association officially becomes the Kentucky League of Women Voters. Mary Bronaugh of Louisville was the first president of the state chapter.

See more on this state's suffrage history at the Kentucky Woman Suffrage Project.

Maryland

The 19th Amendment, which insures women the right to vote, was ratified August 18, 1920.[66] However, Maryland did not ratify the Amendment until March 29, 1941. Indeed, the Maryland Senate and the Maryland House of Delegates both voted against women's suffrage in 1920.[67] In the time between the United States and Maryland approving the amendment, women fought very hard for their rights. In Maryland, there was suffragists and suffrage groups all protesting for women's rights.

Edith Houghton Hooker, born in Buffalo, New York in 1879, was a suffragist in Maryland.[68] She graduated from Bryn Mawr College and later enrolled in the Johns Hopkins University Medical School, where she was one of the first women to be accepted into the program.[68] Hooker was an active member of the suffrage movement.[69] She and her husband, Donald Russell Hooker, were responsible for establishing the Planned Parenthood Clinic in Baltimore.[69] Edith also established the Just Government League of Maryland, which brought the question of women's suffrage to the people of Maryland.[70] In addition to all the things Edith contributed to, she also founded the Maryland Suffrage News.[71] This newspaper was designed to help unite the various suffrage organizations scattered across the state to bring pressure to the legislature to be more sympathetic to the issues of women and to serve as a source of information about suffrage to the women of the state because mainstream papers were virtually blind to the existence of the movement.[71] Hooker saw the need for a focus on passing a national amendment so she did all she could to get the amendment approved.[71]

Etta H. Maddox (c. 1860 - 1933) was the first woman to graduate from Baltimore Law School in 1901, and later to be admitted to the Maryland bar.[72] However, initially she was not permitted to take the exam.[73] The Maryland Court of Appeals rejected her application on the grounds that the wording of Maryland's law only permitted male citizens to practice law.[73][74] Therefore, Maddox and several other female attorneys from other states went to Maryland's General Assembly to lobby for women to be admitted to the Maryland bar. In 1902, a bill introduced by Senator Jacob M. Moses was passed, permitting women to practice law in Maryland.[75] Maddox passed the bar exam with distinction and in September 1902, she was the first woman to become a licensed lawyer in Maryland.[76]

South Carolina

Women's suffrage in South Carolina began as a movement in 1898, nearly 50 years after the women's suffrage movement began in Seneca Falls, New York.

Amongst the leading lights of the movement was Virginia Durant Young, a temperance campaigner who expanded her campaign to push for votes for women in South Carolina elections. Amongst the objections she attempted to argue against was a claim that, because polling booths were often located in bars, the act of voting would take women into unpleasant situations.[77] Her former home is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Tennessee

Woman suffrage entered the public forum in Tennessee in 1876 when a Mississippi suffragist, Mrs. Napoleon Cromwell, spoke before the male delegates to the state Democratic convention held in Nashville. Her ten-minute speech asked the assembly to adopt a resolution for woman suffrage. Her appeal was based in terms of white supremacy. She reasoned that the white race would not be united unless white women were enfranchised. She pointed out that former male slaves could vote, but the wives, daughters, mothers, and sisters of those present at the convention could not. The delegates applauded but they also laughed, treating her speech as a joke. No resolution was passed.[78]

After the Women's Christian Temperance Union national convention in Nashville in 1887, and a powerful appeal by suffragist Rev. Anna Howard Shaw, a group of women in Memphis organized the first woman suffrage league in the state in 1889. Lide Meriwether was elected president and she became active in the National American Woman Suffrage Association as a speaker for other states. In 1895 Meriwether persuaded Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt to come to Memphis where they spoke to white and African American groups and were lauded by the Nineteenth Century Club, the Woman's Council, and the Woman's Club.[79] By 1897 there were ten new clubs in Tennessee, with the largest still in Memphis. A state convention was organized for Nashville that year with Laura Clay of Kentucky and Frances Griffin of Alabama as featured speakers. This convention then formed the Tennessee Equal Rights Association, electing Lide Meriwether president and Bettie M. Donelson of Nashville, secretary.[80] Two separate state associations formed in 1914—the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association and the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association, Incorporated. They both affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and in 1918 combined to form the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Association.[81]

Due to the work by suffragists, in 1919 the Tennessee legislature passed an amendment to the state constitution granting only presidential and municipal suffrage for women. When the Susan B. Anthony amendment came to the Tennessee legislature, thirty-five other states had already ratified it. There was some controversy about the legitimacy of a state constitutional stipulation that a federal amendment could only be voted upon by a legislature that was in place before the amendment was submitted. It took a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court to cause the legislature to reconsider this issue. In addition, Governor Roberts was getting pressure - even from President Woodrow Wilson - to call a special legislative session to consider ratification of the 19th Amendment. Finally, the legislature was called on August 7, 1920. Pro- and anti-suffragist forces came to lobby for their cause.[82] After several days of hearings and debate, the Tennessee State Senate voted for ratification of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment on August 13. On August 17, the house committee on constitutional convention and amendments urged ratification. Debate followed and eventually the house adopted ratification by a majority of fifty to forty-six.[83] With Tennessee as the thirty-sixth state to ratify, the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment was over.[84]

See also

- African-American Woman Suffrage Movement

- Anti-suffragism

- League of Women Voters

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- National American Woman Suffrage Association

- Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Silent Sentinels (1917 imprisonment of suffragettes at the Occoquan Workhouse)

- Suffrage

- Suffrage Hikes

- Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

References

- ↑ Scott and Scott (1982), pp. 16–17

- ↑ Scott and Scott (1982), p. 22

- ↑ Scott and Scott (1982), p. 24

- ↑ Scott and Scott (1982), pp. 31–33

- ↑ Scott and Scott (1982), pp. 43, 45–46

- ↑ Myres, Sandra L., Westering Women and the Frontier Experience, 1800 - 1915, (1982) p. 232

- ↑ Bverly Beeton, "Susan B. Anthony's Woman Suffrage Crusade in the American West," Journal of the West, Apr 1982, Volume 21 Issue 2, pp 5–15

- ↑ Margaret Lyon Wood, "Memorial of Samuel N. Wood," (1891), pp. 23

- ↑ Dudden (2011), pp. 109–110

- ↑ Dudden (2011), p. 115

- ↑ DuBois (1978), pp. 89–90

- ↑ Dudden (2011), pp. 113,127

- ↑ DuBois (1978), p. 92

- ↑ DuBois (1978), pp. 93–94

- ↑ Harper, p. 292

- ↑ DuBois (1978), p. 100

- ↑ Dudden (2011), p. 130

- ↑ DuBois (1978), pp. 80–81

- ↑ "Kansas: Third Time is a Charm". WOW Museum.

- ↑ see facsimile at An Act to Grant to the Women of Wyoming Territory the Right of Suffrage and to Hold Office. Library of Congress. December 10, 1869. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Women vote in the West: the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1869–1896. New York: Garland Science. 1986. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8240-8251-2.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Danilov, Victor J. (2005). Women and museums: a comprehensive guide. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7591-0854-7.

- ↑ White, Jean Bickmore. 2013. Women's suffrage in Utah. http://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/statehood_and_the_progressive_era/womenssuffrageinutah.html

- ↑ Sarah Barringer Gordon, "The Liberty of Self-Degradation: Polygamy, Woman Suffrage, and Consent in Nineteenth-Century America," Journal of American History Vol. 83, No. 3 (Dec., 1996), pp. 815–847 in JSTOR

- ↑ Beverly Beeton, "Woman Suffrage in Territorial Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly, March 1978, Vol. 46 Issue 2, pp 100–120

- ↑ The History of Voting and Elections in Washington State

- ↑ http://theautry.org/explore/exhibits/suffrage/suffrage_wa.html

- ↑ Washington State History Society > Women's History Consortium

- ↑ see facsimile at An act to submit to the qualified electors of the State the question of extending the right of suffrage to women of lawful age, and otherwise qualified, according to the provisions of Article 7, Section 2, of the constitution of Colorado. Library of Congress. April 7, 1893 (adopted by referendum on November 7, 1893 by 35,798 votes to 29,451, ratified by the Governor on December 2, 1893). Retrieved 2007-12-09. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Yung, Judy (1995). Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. University of California Press

- ↑ Ruth Barnes Moynihan, Rebel for Rights: Abigail Scott Duniway (1983)

- ↑ Amy de Haan, "Arizona Women Argue for the Vote," Journal of Arizona History, Winter 2004, Vol. 45 Issue 4, pp 375–394

- ↑ Anna Peterson, "Making Women's Suffrage Support an Ethnic Duty: Norwegian American Identity Constructions and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1880–1925," Journal of American Ethnic History, Summer 2011, Vol. 30 Issue 4, pp 5–23

- ↑ Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, & Anthony, Susan B., & Gage, Matilda Joslyn, History of Women's Suffrage II, Ayer Company Publishers Inc. (1985), 230–232

- ↑ Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, & Anthony, Susan B., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Rutgers University Press (2000) 106

- ↑ Ellen Carol DuBois, "Working Women, Class Relations, and Suffrage Militance: Harriot Stanton Blatch and the New York Woman Suffrage Movement, 1894–1909", Journal of American History, June 1987, Vol. 74 Issue 1, pp 34–58 in JSTOR

- ↑ Constitution of New Jersey, 1776. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ New Jersey Women's History, Rutgers. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ Source, Laws of New Jersey, 1797, "An Act to regulate the election of members of the legislative council and general assembly, sheriffs and coroners, in this State". Courtesy- Special Collections/University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries facsimile here

- 1 2 Nichols, Carole, "Votes and More for Women: Suffrage and After in Connecticut", pp. 5–6, co-published by the Institute for Research in History and the Haworth Press (New York), 1983. Also published as an article in Women & History, No. 5, Spring 1983.

- 1 2 "RG 101, Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, Inventory of Records", Connecticut State Library

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, Harper (1881–1922), History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 3, pp. 321–323. Chapter XXXII, "Connecticut", pp. 316–338 of this book is an early account of the history of women's suffrage in that state.

- ↑ White, Barbara A (2008), The Beecher Sisters, p. 148. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09927-4.

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, Harper (1881–1922), History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 2, p. 764

- ↑ Gordon, Ann D., ed. (2003). The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: National Protection for National Citizens, 1873 to 1880, p. 2. Vol. 3 of 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2319-2.

- 1 2 "19th Amendment: The Fight Over Woman Suffrage in Connecticut", published by connecticuthistory.org, a project of Connecticut Humanities.

- ↑ DuBois, Ellen Carol (1978). Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848-1869, p. 180. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8641-6.

- ↑ Stanton, Anthony, Gage, Harper (1881–1922), Vol. 3, pp. 328–330.

- 1 2 3 4 Jenkins, Jessica D. "The Long and Bumpy Road to Women's Suffrage in Connecticut", Connecticut History, Spring 2016, Vol. 14, No. 2.

- ↑ "Katharine Houghton Hepburn, Class of 1899", the Katharine Houghton Hepburn Center at Bryn Mawr College

- ↑ Nichols, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Quoted in Nichols, p. 20

- ↑ Whites, LeeAnn (2000). The Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta, Georgia, 1860-1890. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (1998). African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Janney, Caroline E. (2008). Burying the Dead But Not the Past: Ladies' Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Cox, Karen L. (2003). Dixie's Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- ↑ "898. An Act to Establish a System of Common Schools in the State of Kentucky". Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, December Session, 1837. Frankfort, Ky.: A.G. Hodges State Printer. 1838. p. 282.

- ↑ Kerr, Andrea Moore (1995). Lucy Stone: Speaking Out for Equality. Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

- ↑ Lucas, Marion (1992). A History of Blacks in Kentucky, Volume 1: From Slavery to Segregation, 1760-1891. Frankfort: The Kentucky Historical Society.

- ↑ Gensemer, Susan H. "Penny, Virginia". American National Biography Online. American Council of Learned Societies. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Fuller, Paul E. (1992). Laura Clay and the Woman's Rights Movement. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 22.

- ↑ Hollingsworth, Randolph. "Mrs. Sarah Clay Bennett speaks before the U.S. Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage". H-Kentucky. H-Net.org. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ Anthony, Susan B.; Husted, Ida Harper, eds. (1902). History of Woman Suffrage, Volume IV: 1883-1900. Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony. p. 669. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ Hay, Melba Porter (2009). Madeline McDowell Breckinridge and the Battle for a New South. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- ↑ Knott, Claudia (1989). The Woman Suffrage Movement in Kentucky, 1879-1920. Lexington, Ky.: Ph.D. diss., University of Kentucky.

- ↑ Mount, Steve. "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". U.S. Constitution. Retrieved 1995. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Why Maryland Rejects the Suffrage Amendment". The New York Times. February 20, 1920. p. 14.

- 1 2 "Maryland Women's Hall of Fame". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved 2001. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - 1 2 "Edith Houghton". Family Tree Maker. Retrieved 2009. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Edith Houghton Hooker (1879-1948): Suffragist, Progressive, and Reformer". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved June 25, 2004.

- 1 2 3 "Woman Suffrage Memorabilia". Word Press.

- ↑ The Honorable Lynn A. Battaglia (2010), ""Where is Justice?" An Exploration of Beginnings" (PDF), University of Baltimore Law Forum, Maryland Finding Justice Project, 41 (1), retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- 1 2 Maryland Commission for Women (2003), Maryland Women's Hall of Fame: Etta H. Maddox, Maryland State Archives, retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- ↑ In re Maddox, 55 L.R.A. 298, 93 Md. 727, 50 A.487 (1901).

- ↑ Maryland General Assembly, Law Record, Resolutions, Ch.399 (1902).

- ↑ Scheeler, Mary Katherine. Notable Maryland Women: Etta Haynie Maddox, 1860–1933. Edited by Winifred G. Helmes. Cambridge: Tidewater Publishers, 1977.

- ↑ "OpenLearn Live: 19th February 2016: A Week in South Carolina: Allendale". OpenLearn. The Open University. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill (1995). Votes for Women: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- ↑ Taylor, Antoinette Elizabeth (1957). The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee. New York: Bookman Associates.

- ↑ Meriwether, Elizabeth Avery (1964). Recollections of 92 Years, 1824-1916. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission.

- ↑ Sims, Anastasia (1991). "'Powers that Pray' and 'Powers that Prey': Tennessee and the Fight for Woman Suffrage". Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Winter).

- ↑ Jones, Robert P.; Byrnes, Mark E. (2009). "The 'Bitterst Fight': The Tennessee General Assembly and the Nineteen Amendment". Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Fall).

- ↑ Casey, Paula F. (Sept/Oct 1995). "The Final Battle: Tennessee's Vote for Women Decided the Nation". Tennessee Bar Journal. 31 (5). Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Yellin, Carol Lynn; Sherman, Janann (1998). The Perfect 36: Tennessee Delivers Woman Suffrage. Tennessee: Iris Press.

Bibliography

- Baker, Jean H. Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists. Hill and Wang, New York, 2005. ISBN 0-8090-9528-9.

- Dubois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women's Movement in America, 1848–1869 (1999)

- Dudden, Faye E. Fighting Chance: The Struggle over Woman Suffrage and Black Suffrage in Reconstruction America. New York: Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-977263-6.

- Hemming, Heidi, and Julie Hemming Savage, Women Making America. Clotho Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-9821271-1-7

- Kraditor, Aileen S. The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement: 1890–1920 (1965) excerpt and text search

- Mead, Rebecca J. How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914 (NYU Press, 2006)

- Scott, Anne Firor and Scott, Andrew MacKay. One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. ISBN 0-252-01005-1

- Ward, Geoffrey C. Not Ourselves Alone: the story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (1999),

- Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls, University of Illinois Press, 2004. ISBN 0-252-02904-6

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Susan B. Anthony; Matilda Joslyn (1922). History of Woman Suffrage. Original from Harvard University: Susan B. Anthony. p. 579.

- Underwood, James L. (1986). The Constitution of South Carolina: The struggle for political equality. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 59–94. ISBN 978-0-87249-978-2.

- Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 471–. ISBN 978-1-57003-255-4.

- Bass, Jack; Poole, W. Scott (5 June 2012). The Palmetto State: The Making of Modern South Carolina. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-1-61117-132-7.

Further reading

- Knobe, Bertha Damaris (August 1911). "Recent Strides Of Woman Suffrage". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII (1): 14733–14745. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

External links

- UNCG Special Collections and University Archives selections of American Suffragette manuscripts

- International Woman Suffrage Timeline: Winning the Vote for Women Around the World provided by About.com

- Woman's Suffrage Association and League of Women Voters Collection (MS-004), a manuscripts collection at Dayton Metro Library

- The Sewall-Belmont House & Museum--Home of the historic National Woman's Party

- Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party

- Oral History Interview with Eulalie Salley at Oral Histories of the American South