Williamina Fleming

| Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming | |

|---|---|

Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming | |

| Born |

May 15, 1857 Dundee, Scotland |

| Died |

May 21, 1911 (aged 54) Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | None |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (May 15, 1857 – May 21, 1911) was a Scottish-American astronomer. During her career, she helped develop a common designation system for stars and cataloged thousands of stars and other astronomical phenomena. Among several career achievements that advanced astronomy Fleming is noted for her discovery of the Horsehead Nebula in 1888.[1]

Biography

Williamina Stevens was born on May 15, 1857, to Mary and Robert Stevens; he a carver and gilder of Dundee, Scotland. There, in 1877, she married James Orr Fleming, an accountant and widower of Dundee. She worked as a teacher a short time before the couple emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts, USA, when she was 21.[2]

Harvard College Observatory

After she and her child were abandoned by James Fleming, she worked as a maid in the home of Professor Edward Charles Pickering, who was director of the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). The story was told that Pickering was often frustrated with the performance of the (all-male) "computers" at the observatory and, reportedly, would complain loudly: "My Scottish maid could do better!"[3] Pickering's wife recommended Fleming as having talents beyond custodial and maternal arts.[4]

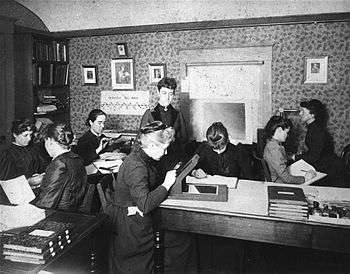

Shortly after the donations from Mrs. Draper, one of the existing computers, Nettie Farrar, became engaged.[4] Pickering chose Fleming to replace her as a computer, and made her supervisor of the 14 existing female computers.[4] In 1881 Pickering hired Fleming to join the HCO and taught her how to analyze stellar spectra; she was the first of an all-women cadre of human "computers" created by Pickering at HCO.[3]

Pickering first challenged Fleming to improve a preexisting classification of stars.[4] The Harvard Observatory images contained photographed spectra of stars that reached the ultraviolet range, this allowed much more accurate classifications of stars to be performed when compared to recording spectra by hand through an instrument at night.[4] As a result of the work of the women "computers", Pickering published in 1890 the first Henry Draper Catalog, a catalog with more than 10,000 stars classified according to their spectrum. The majority of these classifications were done by Fleming.[5] She also made it possible to go back and compare recorded plates, by organizing thousands of photographs by telescope along with other identifying factors.[4]

Soon she devised a system for classifying stars according to the relative amount of hydrogen observed in their spectra. (Stars showing hydrogen as the most abundant element were classified A; those of hydrogen as the second-most abundant element, B; and so on.) Later, Annie Jump Cannon developed an improved classification system based upon the surface temperature of stars.

Fleming contributed to the cataloging of stars that later were published as the Henry Draper Catalogue. In nine years' effort she cataloged more than 10,000 stars. During her career she discovered 59 gaseous nebulae, over 310 variable stars, and 10 novae. In 1907 she published a list of 222 variable stars she had discovered.

In 1888, Fleming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on a telescope-photogrammetry plate made by astronomer W. H. Pickering, brother of E.C. Pickering; she described the bright nebula (later known as IC 434) as having "a semicircular indentation 5 minutes in diameter 30 minutes south of Zeta Orionis". Subsequent professional publications neglected to give credit to Fleming and W. H. Pickering for the discovery; the first Dreyer Index Catalogue omitted Fleming's name from the list of contributors having then discovered sky objects at Harvard, attributing the entire work merely to "Pickering"—presumably to mean E. C. Pickering, director of HCO. But by the time of the second Dreyer Index Catalogue, in 1908, Fleming and her colleagues at HCO were sufficiently well-known to receive proper credit for their discoveries; still, her first observation of the Horsehead Nebula was typically uncredited.

In 1886 Fleming was placed in charge of the dozens of women hired to compute mathematical classifications and edit the observatory's publications. Fleming openly advocated for other women in the sciences in her talk "A Field for Woman's Work in Astronomy" at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, where she openly promoted the hiring of female assistants in astronomy. Her speech suggested she agreed with the prevailing idea that women were inferior, but felt that it given greater opportunities they would be able to become equals, in other words the sex differences in this regard were more culturally constructed than biologically grounded.[6]

In 1899, she was made Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard, and in 1906, she was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the first American woman to be so honored.[2] Soon after she was appointed honorary fellow in astronomy of Wellesley College. Shortly before her death the Astronomical Society of Mexico awarded her the Guadalupe Almendaro medal for her discovery of new stars. She published A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907). She is credited with the discovery of the first white dwarf.

The first person who knew of the existence of white dwarfs was Mrs. Fleming; the next two, an hour or two later, Professor E. C. Pickering and I. With characteristic generosity, Pickering had volunteered to have the spectra of the stars which I had observed for parallax looked up on the Harvard plates. All those of faint absolute magnitude turned out to be of class G or later. Moved with curiosity I asked him about the companion of 40 Eridani. Characteristically, again, he telephoned to Mrs. Fleming who reported within an hour or so, that it was of Class A.

She published her discovery of white dwarfs (1910).[2] Also she published Spectra and Photographic Magnitudes of Stars in Standard Regions (1911).

She died in Boston on May 21, 1911.[2]

Honors

- The lunar crater Fleming was jointly named after her and (not closely related) Alexander Fleming.

- In 1906, she was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the first American woman to be so elected.[2]

Legacy

The Harvard women "computers" were famous during their lifetimes, but largely forgotten in the following century. In about 2015 Lindsay Smith Zrull, curator of Harvard's Plate Stacks collection, while trying to catalogue, digitize, and attribute the astronomical plates for DASCH, found about 118 total boxes, each containing 20 to 30 notebooks, from women computers and early Harvard astronomers. Realizing that the 2,500+ volumes were outside the scope of her work with DASCH, but wanting to see the material preserved and made accessible, Lindsay reached out to librarians at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Starting from a catalogue created by Joe Timko in the 1970s, Wolbach Library launched Project PHaEDRA (Preserving Harvard's Early Data and Research in Astronomy).[7] As of August 2017 about 200 of the volumes had been transcribed; two of the women computer's notebooks (not yet including Fleming) were listed via the Smithsonian Digital Volunteers Web site, which requested volunteers to transcribe them, a task expected to take years for all the notebooks.[8] Daina Bouquin, Wolbach's Head Librarian, said that the objective is to enable full-text search of the research: "If you search for Williamina Fleming, you're not going to just find a mention of her in a publication where she wasn't the author of her work. You're going to find her work."

In July 2017 the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics's Wolbach Library unveiled a display showcasing Fleming's work,[9] including the log book containing the Horsehead Nebula discovery.[7] The library has dozens of volumes of Fleming's work in its PHaEDRA collection.[10]

References

- ↑ Cannon, Annie J. (June 1911). "WILLIAMINA PATON FLEMING". Science (published June 30, 1911). 33 (861): 987–988. Bibcode:1911Sci....33..987C. doi:10.1126/science.33.861.987. PMID 17799863.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Women Working 1800-1930, Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857–1911)". Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. Retrieved 28 August 2017. With links to manuscripts and other resources.

- 1 2 Smith, Lindsay (March 14, 2015). Williamina Paton Fleming. Project Continua. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

- ↑ Harvard University. "About the Collection", Harvard.edu, .

- ↑ Rossiter, Margaret W. (1980). ""Women's Work" in Science, 1880-1910". Isis. 71 (3): 381–398. JSTOR 230118.

- 1 2 Alex Newman (28 August 2017). "Unearthing the legacy of Harvard's female 'computers'". BBC News. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ "Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics: Browse Projects". Smithsonian Digital Volunteers. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ Alex McGrath (3 July 2017). "The First Computer: Williamina Fleming and the Horsehead Nebula". Galactic Gazette. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ↑ "Harvard College Observatory observations, logs, instrument readings, and calculations: an inventory". Harvard Library. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

Further reading

- Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. Penguin. ISBN 9780670016952.

- Shearer, Benjamin (1997). Notable women in the physical sciences : a biographical dictionary (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313293030.

External links

- The discovery of early photographs of the Horsehead nebula, by Waldee & Hazen

- The Horsehead Nebula in the 19th Century, by Waldee (archived)

- Astrophysical Journal, vol. 34, p.314

- Bibliography from the Astronomical Society of the Pacific

- Project Continua: Biography of Williamina Paton Fleming Project Continua is a web-based multimedia resource dedicated to the creation and preservation of women’s intellectual history from the earliest surviving evidence into the 21st Century.

- Birth and Marriage details from Scotland's People website http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/ : Statutory Birth Record 282/02/0700; Statutory Marriage Record 282/03/0098