William Maclure

| William Maclure | |

|---|---|

William Maclure | |

| Born |

27 October 1763 Ayr, Scotland |

| Died |

23 March 1840 (aged 76) San Ángel, Mexico |

| Citizenship | American |

| Known for | First geological map of America 1809, and New Harmony Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | geology, education, philanthropy |

William Maclure (27 October 1763 – 23 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist.[1] He is known as the 'father of American geology' [2] and as a social experimenter on new types of community life, collaborating with British social reformer Robert Owen, (1771–1854), in Indiana, United States.

Maclure had a highly successful mercantile career, making a fortune that allowed him to retire in 1797 at the early age of 34 to pursue his scientific, geological and other interests. In 1809 he made the earliest attempt at a geological map of the United States of America.[3]

Biography

Early life, business, and education

Maclure was born in 1763 in Ayr, Scotland.

After a brief visit to New York City in 1782, he began work with the merchants Miller, Hart & Co, who traded and shipped goods to and from America. Maclure was based in the London office but regularly travelled to France and Ireland on business.[4] In 1796 business affairs took him to Virginia, which he thereafter made his home. In 1803 he visited France as one of the commissioners appointed to settle the claims of American citizens on the French government; and during the few years then spent in Europe he applied himself with enthusiasm to the study of geology. While residing in Switzerland, he became impressed with what is now called the Pestalozzi School System, from Swiss pedagogist Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827).

Geological map

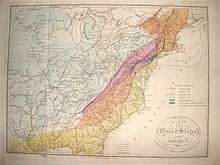

On his return home in 1807 he commenced the self-imposed task of making a geological survey of the United States. Almost every state in the Union was traversed and mapped by him, the Allegheny Mountains being crossed and recrossed some 50 times.[5] The results of his unaided labours were submitted to the American Philosophical Society in a memoir entitled Observations on the Geology of the United States explanatory of a Geological Map, and published in the Society's Transactions (vol. iv. 1809, p. 91) together with the first geological map of that country. Maclure's 1809 Geological Map This antedates William Smith's geological map of England and Wales (with part of Scotland) by six years, although it was constructed using a different classification of rocks.

In 1812, while in France, Maclure became a member of the newly founded Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP). In 1817 Maclure became president of the ANSP, a post he held for the next 22 years.

In 1817, while residing in Europe, Maclure brought before the same society a revised edition of his map, and his great geological memoir, which he had issued separately, with some additional matter, under the title Observations on the Geology of the United States of America.[6] Subsequent surveys have corroborated the general accuracy of Maclure's observations.

Later years

In 1819 he visited Spain, and attempted, unsuccessfully, to establish an agricultural college near the city of Alicante. Returning to America in 1824, he settled for some years at New Harmony, Indiana, seeking to develop his vision of the agricultural college. Failing health ultimately required him to relinquish the attempt and to seek (in 1827) a more congenial climate in Mexico. There, in 1840, at San Ángel, he died aged 77. His will provided for a trust fund consisting of most of his property. Under the terms of the Trust, 160 workingmen's libraries were established. The treatment of Maclure's burial site in Mexico was bereft of the honors due the respected humanitarian and geologist:

Summary of the second phase of Maclure's life (after Moore 1947) [8]

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1778-1797 Mercantile career, based in London but with regular contact and travel to America | |

| 1796 | Emigrated to the United States, settling in Philadelphia and became an American citizen. |

| 1797 | Retirement from business (Silliman claims this was 1799, Monroe claims 1803) |

| 1799 | Elected to American Philosophical Society. Council 1818-1829. |

| 1803 | Member of Spoliation Commission in France. |

| 1803-1805 and subsequent years | Visits to Pestalozzi and other schools and travels and geological work in Europe. |

| 1805 | Brought Joseph Neef to Philadelphia to establish first Pestalozzian schools. |

| 1805-1817 | One-man geological survey. First report and geological map published 1809, extended and revised 1817. |

| 1812 | Member of Academy of Natural Sciences (President 1817-1840). |

| 1817-1819 | Exploring trips to Georgia, Florida, and the Lesser Antilles Islands. |

| 1819 | First President of American Geological Society |

| 1819-1824 | Agricultural and industrial schools at Alicante, Spain. |

| 1824-1828 | With a body of teachers and scientists joined Robert Owen's colony at New Harmony. Established Pestalozzian, manual training and industrial schools and scientific center and library. |

| 1826 | Established New Harmony Educational Society and night-school for adults. |

| 1827 | With Thomas Say spent winter in Mexico. |

| 1828 | Health failing. Attended meeting of Armerican Geological Society for the last time. |

| 1828 | Founded New Harmony Disseminator of Useful Knowledge at Industrial School. |

| 1828-1840 | Residence in Mexico. |

| 1831 | Publication of Opinions on Various Subjects. |

| 1836 | Serious illness . |

| 1837 | Rejuvenated Workingmen's Institute and library. |

| 1840 | Death in Mexico, 23 March. Will provided for a trust fund of most of his property under which160 workingmen's libraries were established. |

New Harmony

The New Harmony commune in Indiana produced a number of geologists, naturalists, and botanists which were influenced by Maclure, such as: Robert Dale Owen (1801–1877), social reformer; David Dale Owen (1807–1860), geologist, artist; Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy (1806–1861), educator; and Richard Owen (1810–1890) geologist, first president of Purdue University, Lafayette, Indiana. They interacted there with a formidable crop of contemporary geologists, social reformers, botanists, paleobotanists, ethnologists, civil engineers, etc.

European Journals

The European Journals of William Maclure[9] was a monumental book, describing, charting, and chronicling much of the features of Europe.

Honors, awards, and tributes

- Mount Maclure in Yosemite National Park is named after Maclure.[10]

- Maclure Glacier one of the last remaining glaciers in Yosemite National Park is also named for William Maclure.[11][12]

- Maclura a genus of flowering plants in the mulberry family, Moraceae is named in honor of Maclure. The genus includes the inedible Osage-orange, which is used as mosquito repellent and grown throughout the United States as a hedging plant.[13]

- Macluritidae an extinct family of relatively large, Lower Ordovician to Devonian, macluritacean gastropods is named in honor of Maclure.[14]

- Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1836

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Bantu, Richard E. (1948). "New Harmony's Golden Years". Indiana Magazine of History (1): 26. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ Merrill, G.P. (1904) Contributions to the history of American geology. Rep. US Natn. Mus. For 1904, Gov Printing Office, Washington D.C.

- ↑ Merrill, G.P. (1904) Contributions to the history of American geology. Rep. US Natn. Mus. For 1904, Gov Printing Office, Washington D.C., 189-733, 1906

- ↑ Donachie, I. William Maclure: Science, Pestalozzianism and Reform in Europe and the United States Accessed 26 August 2012

- ↑ Page 39 in Greene, J.C. and Burke, J.G. (1978) The Science of Minerals in the Age of Jefferson. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 1-113

- ↑ Maclure, William. Observations on the Geology of the United States of America. Abraham Small, Philadelphia, 1817.

- ↑ Mexico the Way It Was and Is.(1847) p.158 at archive.org

- ↑ J. Percy Moore (1947) William Maclure - Scientist and Humanitarian Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 91, No. 3. pp.234-249

- ↑ The European Journals of William Maclure. William Maclure, edited by John S. Doskey. Diane Publishing, (1988), ISBN 0-87169-171-X, 9780871691712), 815 pages.

- ↑ Farquhar, Francis P. (1926). Place Names of the High Sierra. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ↑ Mount Lyell, CA (Map). TopoQwest (United States Geological Survey Maps). Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- ↑ "Maclure Glacier". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- ↑ Burton, J D (1990). "Maclura pomifera". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2. Retrieved 2009-03-03 – via Southern Research Station (www.srs.fs.fed.us).

- ↑ Benjamin Eli Smith (1899). The Century dictionary and cyclopedia. The Century co. pp. 3562–.

Further reading

- Harvey L. Carter, "William Maclure," Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 31, no. 2 (June 1935), pp. 83–91. In JSTOR

- Alberto Gil Novales, Maclure en España. Iniciativas de Cultura, 1981.

- Donald E. Pitzer, "William Maclure's Boatload of Knowledge: Science and Education into the Midwest", Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 94, (1998), pp. 110–135.

- Leonard Warren, Maclure of New Harmony: Scientist, Progressive Educator, Radical Philanthropist. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009.

![]()

External links

- Biography of William Maclure by James S. Aber

- William Maclure at University of Evansville

- New Harmony Workingmen's Institute, legacy of William Maclure at University of Evansville

- History of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

- New Harmony Scientists, Educators, Writers & Artists at University of Evansville