Wide Sargasso Sea

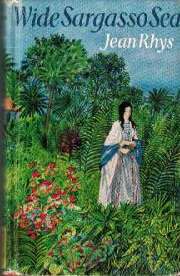

First edition cover | |

| Author | Jean Rhys |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Eric Thomas |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Postmodern novel |

| Publisher | André Deutsch (UK) & W. W. Norton (US) |

Publication date | October 1966 |

| ISBN | 0-233-95866-5 |

| OCLC | 4248898 |

Wide Sargasso Sea is a 1966 novel by Dominica-born British author Jean Rhys. The author lived in obscurity after her previous work, Good Morning, Midnight, was published in 1939. She had published other novels between these works, but Wide Sargasso Sea caused a revival of interest in Rhys and her work and was her most commercially successful novel. It is a feminist and anti-colonial response to Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre (1847), describing the background to Mr Rochester's marriage from the point-of-view of his mad wife Antoinette Cosway, a Creole heiress. Antoinette Cosway is Rhys' version of Brontë's devilish "madwoman in the attic". Antoinette's story is told from the time of her youth in Jamaica, to her unhappy marriage to a certain unnamed English gentleman, who renames her Bertha, declares her mad, and then takes her to England. Antoinette is caught in an oppressive patriarchal society in which she neither fully belongs to Europe nor Jamaica. Wide Sargasso Sea explores the power relationships between men and women and develops postcolonial themes, such as racism, displacement and assimilation.

Plot

The novel, initially set in Jamaica, opens a short while after the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 ended slavery in the British Empire on 1 August 1834.[1] The protagonist Antoinette relates the story of her life from childhood to her arranged marriage to an unnamed Englishman.

The novel is in three parts:

Part One takes place in Coulibri, Jamaica, and is narrated by Antoinette as a child. Since the abolition of slavery caused her family to become very poor, Antoinette's mother, Annette, must remarry to wealthy Englishman Mr. Mason. Angry at the returning prosperity of their oppressors, freed slaves living in Coulibri burn down Annette's house, killing Antoinette's mentally disabled younger brother. As Annette had been struggling with her mental health up until this point, the grief of losing her son weakens her sanity. Mr. Mason sends her to live with a couple who torment her until she dies and Antoinette does not see her again.

Part Two alternates between the points of view of Antoinette and her husband during their honeymoon excursion to Granbois, Dominica. Likely catalysts for Antoinette's downfall are the mutual suspicions that develop between the couple, and the machinations of Daniel, who claims he is Antoinette's illegitimate, half-brother; he impugns Antoinette's reputation and mental state and demands money to keep quiet. Antoinette's old nurse Christophine openly distrusts the Englishman. His apparent belief in the stories about Antoinette family and past aggravate the situation; her husband is unfaithful and emotionally abusive. He begins to call her Bertha rather than her real name and flaunts his affairs in front of her to cause her pain. Antoinette's increased sense of paranoia and the bitter disappointment of her failing marriage unbalance her already precarious mental and emotional state. She flees to Christophine's house, the servant woman who raised her. Antoinette pleads with Christophine for an obeah potion to attempt to reignite her husband's love, which Christophine reluctantly gives her. Antoinette returns home but the love potion acts like a poison on her husband. Subsequently he refuses Christophine's offer of help for his wife and takes her to England.

Part Three is the shortest part of the novel; it is from the perspective of Antoinette, renamed by her husband as Bertha. She is largely confined to "the attic" of Thornfield Hall, the mansion she calls the "Great House". The story traces her relationship with Grace Poole, the servant who is tasked with guarding her, as well as her disintegrating life with the Englishman, as he hides her from the world. He makes empty promises to come to her more but sees less of her. He ventures away to pursue relationships with other women—and eventually with the young governess. It is clear that Antoinette is mad and has little understanding of how much time she has been confined. She fixates on options of freedom including her stepbrother Richard who, however, will not interfere with her husband, so she attacks him with a stolen knife. Expressing her thoughts in stream of consciousness, Antoinette dreams of flames engulfing the house and her freedom from the life she has there, and believes it is her destiny to fulfill the vision. Waking from her dream she escapes her room, sets the fire.

Major themes

Since the late 20th century, critics have considered Wide Sargasso Sea as a postcolonial response to Jane Eyre.[2][3] Rhys uses multiple voices (Antoinette's, her husband's, and Grace Poole's) to tell the story, and intertwines her novel's plot with that of Jane Eyre. In addition, Rhys makes a postcolonial argument when she ties Antoinette's husband's eventual rejection of Antoinette to her Creole heritage (a rejection shown to be critical to Antoinette's descent into madness). The novel is also considered a feminist work, as it deals with unequal power between men and women, particularly in marriage.

Race

Antoinette and her family had been slave owners up until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and subsequently lost their wealth. They are called "white nigger" by the Island's negroes because of their poverty and are openly despised. Rochester, as an Englishman, looks down on Antoinette because she is a Creole. Antoinette is not English and yet her family history privilege her as a white woman. Lee Erwin describes this paradox through the scene in which Antoinette's first house is burned down and she runs to Tia, a black girl her own age, to "be like her". Antoinette is rebuffed by violence from Tia leading to her seeing Tia "as if I saw myself. Like in a looking glass". Erwin argues that "even as she claims to be seeing "herself," she is simultaneously seeing the other, that which only defines the self by its separation from it, in this case literally by means of a cut. History here, in the person of a former slave's daughter, is figured as refusing Antoinette", the daughter of a slave owner.[4]

Colonialism

In Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys draws attention to colonialism and the slave trade by which Antoinette ancestors had made their fortune. The novel does not shy away from uncomfortable truths about British history that had been neglected in Bronte's narrative. Trevor Hope remarks that the "triumphant conflagration of Thornfield Hall in Wide Sargasso Sea may at one level mark a vengeful attack upon the earlier textual structure". The destruction of Thornfield Hall occurs in both novels; however, Rhys epitomises the fire as a liberating experience for Antoinette. If, then, Thornfield Hall represents domestic ideas of Britishness, then Hope suggests Wide Sargasso Sea is "taking residence inside the textual domicile of empire in order to bring about its disintegration or even, indeed, its conflagration."[5]

Awards and nominations

- Winner of the WH Smith Literary Award in 1967, which brought Rhys to public attention after decades of obscurity.

- Named by Time as one of the 100 best English-language novels since 1923.[6]

- Rated number 94 on the list of Modern Library's 100 Best Novels

- Winner of Cheltenham Booker Prize 2006 for year 1966.

Adaptations

- 1993: Wide Sargasso Sea, film adaptation directed by John Duigan and starring Karina Lombard and Nathaniel Parker.

- 1997: Wide Sargasso Sea, contemporary opera adaptation with music by Brian Howard, directed by Douglas Horton.

- 2004: Wide Sargasso Sea, BBC Radio 4 10-part adaptation by Margaret Busby, read by Adjoa Andoh (repeated 2012, 2014).

- 2006: Wide Sargasso Sea, TV adaptation directed by Brendan Maher and starring Rebecca Hall and Rafe Spall.

- 2011: "Wide Sargasso Sea", song written by rock 'n' roll singer Stevie Nicks about the novel and film; it appears on her 2011 album In Your Dreams.

See also

References

- ↑ "Emancipation", The Black Presence, National Archive.

- ↑ "Wide Sargasso Sea at The Penguin Readers' Group". Readers.penguin.co.uk. 3 August 2000. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Empire Writes Back: Jane Eyre". Faculty.pittstate.edu. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Erwin, Lee (1989). "'Like in a Looking-Glass': History and Narrative in Wide Sargasso Sea". Novel: A Forum on Fiction.

- ↑ Hope, Trevor (2012). "Revisiting the Imperial Archive: Jane Eyre, Wide Sargasso Sea, and the Decomposition of Englishness". College Literature.

- ↑ Lacayo, Richard (16 October 2005). "Time magazine list of All-Time 100 Novels". Time. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

External links

- "Wide Sargasso Sea, Bertha and Jane Eyre", The Magpie Poet blog

- Wide Sargasso Sea, study guide, themes, quotes, & teacher resources

- Review JaneEyre.net