White slave propaganda

White slave propaganda is the term given to publicity, especially photograph and woodcuts, and also novels, articles, and popular lectures, about mixed-race, white-looking slaves, which was used during and prior to the American Civil War to further the abolitionist cause and to raise money for the education of former slaves. The images included children with predominantly European-American features photographed alongside dark-skinned adult slaves with typically African-American features. It was intended to shock the viewing audiences with a reminder that slaves shared their humanity, and evidence that slaves did not belong in the category of the "Other".

Early publicity about white slave children

Sexual exploitation of slaves by their masters, master's sons, overseers or other powerful white men was common in the United States. By the 1860 census, mixed-race slaves constituted about 10% of the 4 million slaves enumerated; they were more numerous in the Upper South. Slavery had existed for a longer time there, and in the generally smaller holdings, slaves had lived more closely with white workers and masters, leading to more contact with whites. About 5% of slaves born in the Southern US are believed to have been fathered by white masters.

An analysis of the WPA Slave Narrative Collection, collected in the 1930s, shows that, when women discussed parentage at all, about one-third of these women ex-slaves said they had given birth to a child with a white father, or were themselves the child of a white father.[1] The plight of these mixed-race slaves, especially as children, was often publicized as a way to further the abolitionist cause.

The character of Eliza in the 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was described as a quadroon slave (¼ black ancestry) whose child also appeared to be "all-but-white".[2] Carol Goodman states that these literary "white slaves" existed visually only in the imagination of the readers. But later photographs documented the existence of mixed-race, predominantly white slaves, whose appearance shocked and titillated many Northerners.[3]

Nonfiction accounts written by escaped mixed-race slaves who used their European appearance to "pass for white" and gain freedom include those of Ellen Craft: Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (coauthored with her husband William), and Harriet Ann Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.[4][5] With majority-white ancestry, these women often also appeared as speakers on the abolitionist lecture circuit.[6]

The Crafts and other abolitionists also publicized the life of Salomé Müller, a German immigrant orphaned as an infant soon after arrival in New Orleans. Though Muller (later known as Sally Miller) was completely of European descent, she became enslaved as an infant, treated as a mixed-race slave. The threat of white girls being seized and thrown into slavery prompted Parker Pillsbury to write to William Lloyd Garrison: "A white skin is no security whatsoever. I should no more dare to send white children out to play alone, especially at night... than I should dare send them into a forest of tigers and hyenas."[7]

Another popular abolitionist novel of the time was Mary Hayden Pike's Ida May: a Story of Things Actual and Possible (1854), a story about a "white" slave. In 1855, Mary Mildred Botts, a young white slave, gained freedom with the help of Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who adopted her. She was considered the embodiment of Ida May. Articles were published about her in the Boston Telegraph and the New York Times, and copies of her photograph were widely publicized.[8][9][10] Botts appeared on stage during speeches by Sumner and other abolitionists. On May 19 and 20, 1856, Sumner spoke in the Senate comparing Southern political positions to the sexual exploitation of slaves then taking place in the South. Two days later Sumner was beaten almost to death on the floor of the Senate in the Capitol by Representative Preston Brooks from Georgia, known as a hothead.[10]

Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence was a young white slave freed in early 1863. She was adopted by Catherine S. Lawrence of New York and baptized by Henry Ward Beecher at the Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York. Carte de visite photographs of her were also sold to raise money for the abolitionist cause.[11]

Mary Mildred Botts in an 1855 daguerreotype

Mary Mildred Botts in an 1855 daguerreotype Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence, a slave freed in early 1863

Fannie Virginia Casseopia Lawrence, a slave freed in early 1863 Etching of Ellen Craft based on a c. 1860 photo

Etching of Ellen Craft based on a c. 1860 photo Harriet Ann Jacobs in 1894

Harriet Ann Jacobs in 1894

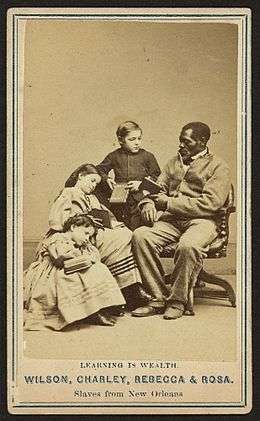

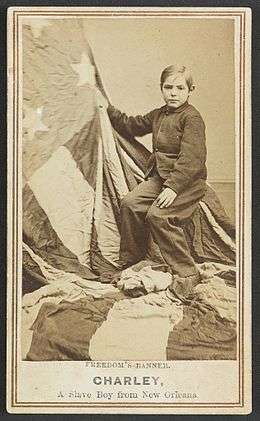

Freed slaves from Louisiana

By 1863 in Louisiana, ninety-five schools for freedmen, serving 9,500 students, were active in areas controlled by the Union Army. Funding was needed to continue to run the schools. The National Freedman's Association, the American Missionary Association, and Union officers launched a publicity campaign to raise money by selling carte de visite (CDV) photographs of eight former slaves, five children and three adults. The former slaves were accompanied on a tour of Philadelphia and New York by Colonel George H. Hanks. A woodcut, based on a photograph of the former slaves, appeared in Harper's Weekly in January 1864 with the caption "EMANCIPATED SLAVES, WHITE AND COLORED."[12] Four of the children were predominantly white in appearance, although born into slavery.

Tour

The former slaves traveled from New Orleans to the North. Of these, four children appeared to be white or octoroon. According to the Harper's Weekly article, they were, "'perfectly white;' 'very fair;' 'of unmixed white race.' Their light complexions contrasted sharply with those of the three adults, Wilson, Mary, and Robert; and that of the fifth child, Isaac—'a black boy of eight years; but nonetheless [more] intelligent than his whiter companions.'"[12][13][14]

The group was accompanied by Colonel Hanks from the 18th Infantry Regiment. They posed for photos in New York City and in Philadelphia. The resulting images were produced in the carte de visite format and were sold for twenty-five cents each, with the profits of the sale being directed to Major General Nathaniel P. Banks back in Louisiana to support education of freedmen. Each of the photos noted that sale proceeds would be "devoted to the education of colored people".[12][13]

Legacy

Of the many prints that were commissioned, at least twenty-two remain in existence today. Most of these were produced by Charles Paxson and Myron Kimball, who took the group photo that later appeared as a woodcut in Harper's Weekly. A portrait of Rebecca was taken by James E. McClees of Philadelphia.[12]

Modern analysis

Modern scholars have examined the white slave campaign's motives and success. Mary Niall Mitchell in "Rosebloom and Pure White, Or So It Seemed,"[15] argues that because the slaves were depicted as being white, through both their skin color and style of dress, abolitionists could argue that the American Civil War was independent of class status. Supporters of the war believed that this was needed after the draft riots in New York City that year. Predominantly ethnic Irish mobs had protested the draft law, as wealthier men could buy substitutes rather than serve in the war.

Carol Goodman in "Visualizing the Color Line," has argued that the photos alluded to physical and sexual abuse of the children's mothers. When publishing the photo of the eight former slaves, the editor of Harper's Weekly wrote that slavery permits slave-holding, "'gentlemen' [to] seduce the most friendless and defenseless of women." The specter of "white" girls being sold as "fancy girls" or concubines in southern slave markets may have caused northern families to fear for the safely of their own daughters. Similarly the idea that white slave-master fathers would sell their own children in slave markets raised northerners' concerns.

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, in "Portraits of a People," has argued that the usage of props, such as the American flag and books, helped to provide context for Northern viewers, and also to emphasize that the purpose of the photos was to raise money for education of former slaves and schools in Louisiana. She also noted that the use of "white" children to illustrate the damage caused by institutional slavery, whose victims were overwhelmingly visibly people of color, demonstrated the contemporary racism of both southern and northern societies.[12]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Free at Last? Slavery in Pittsburgh in the 18th and 19th Centuries". University Library System. University of Pittsburgh. 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ↑ Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1852). Uncle Tom's Cabin. p. 20. Retrieved July 5, 2016. See, in particular, Chapter II

- ↑ Goodman, Carol. ""As White As Their Masters": Visualizing the Color Line". mirrorofrace.org. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ↑ Craft, William and Ellen (1860). Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. p. 63. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ Jacobs, Harriet Ann (1861). Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

- ↑ Barbara McCaskill, "William and Ellen Craft", New Georgia Encyclopedia, 2010, accessed July 6, 2016

- ↑ Carol Wilson, "Sally Muller, the White Slave", Louisiana History, Vol. 40, 1999, accessed July 7, 2016

- ↑ "A White Slave from Virginia". New York Times. March 9, 1855. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- ↑ Gage, Joan. "A White Slave Girl "Mulatto Raised by Charles Sumner"". Mirror of Race. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- 1 2 Morgan-Owens, Jessie (February 19, 2015). "Poster Child: There's Something About Mary". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Tanya Ballard (December 10, 2012). "A Black And White 1860s Fundraiser". NPR. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Caust-Ellenbogen, Celia. "White Slaves". Bryn Mawr College, Swarthmore College. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- 1 2 "'White' slave children of New Orleans". New York Daily News. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "The 'white' slave children of New Orleans: Images of pale mixed-race slaves used to drum up sympathy among wealthy donors in 1860s". 27 February 2012. London: Daily Mail. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ Mitchell, Mary Niall. "'Rosebloom and Pure White,' Or So It Seemed". ScholarWorks@UNO. University of New Orleans. Retrieved June 29, 2016. also published in American Quarterly 54:3 (September 2002): 369-410

Further reading

- Tenzer, Lawrence Raymond (1997). The Forgotten Cause of the Civil War: A New Look at the Slavery Issue. Scholars' Publishing House. See especially Ch.III

- Fremont Campaign Literature, 1856

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Exactly How ‘Black’ Is Black America?

- Janken, Kenneth Robert (2006). Walter White: Mr. NAACP. UNC Press Books. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9780807857809.

External links

![]()

![]()