When I Was One-and-Twenty

When I Was One-and-Twenty is the first line of the untitled Poem XIII from A. E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad (1896). It is often anthologised and given musical settings under that title. The piece is simply worded but contains references to the now superseded coins, guineas and crowns.[1]

Musical settings

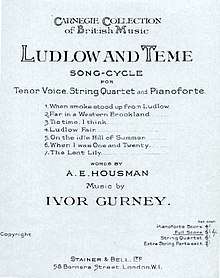

Housman’s poem was among the first to be set by composers, beginning with Arthur Somervell’s as part of his Songcycle from A Shropshire Lad and the single setting by Stephen Adams, both in 1904.[2] Two frequently performed versions are George Butterworth’s, from his Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad for medium high voice and piano (1911),[3] and Ivor Gurney’s from Ludlow and Teme (1919).[4] The style of setting varies from the simplicity of the traditional tune fitted to it by Butterworth to the “chromatically overwrought” music of Arnold Bax.[5] Some 43 versions are currently listed on The LiederNet Archive[6] but they do not include arrangements for choir such as those by Richard Nance as part of Songs of a Young Man (1985)[7] and Robert Rhein in Three Songs from A Shropshire Lad.[8] There have also been popular versions, as in the solo performance by Michael Nesmith[9] and the group performance by the German folk group, Black Eye.[10]

Proposition

This poem was written when Housman was a young man, just like many of his other poems. Many of his poems are told in the first person; therefore, one can only assume that this particular poem was written out of an experience Housman himself had gone through. The particular poem demonstrates the vivacity of a vulnerable youth falling for love: “But I was one-and-twenty, no use talking to me” (7-8). The youth intentionally proceeds to fall in the pits of love, knowing what could become of it. He is even acknowledging that he understands the consequences, which is a broken heart, but shows no desire to the reader of preventing it. In the poem, the character is warned not to give his heart away out of lust, but to guard it with care as it is shown in this quote from the poem, “Give crowns and pounds and guineas, but not your heart away” (3-4). When the end of the poem is reached, the reader then understands the intention of the poem was not blithe, but the opposing adjective as Housman writes “I am two-and-twenty and oh ’tis true ’tis true” (15-16). This line makes it clear to the reader that the twenty two year old ignored the wise man’s warning and has since come to regret it. The twenty two year not only regrets giving his heart away, but also now goes on to warn other youths of the dangers of love. Housman wrote his poem in the sense that, “Love has to be separated from the daily business of living before any pleasure can be found in it (though even that pleasure can cause the lover to be viewed as an almost ridiculous figure)” (Blocksidge). This allows the reader to consider the fact that love is not what it is made out to be.

Ignorance

Apart from the proposition, the ignorance that is portrayed is also a big key concept of this poem. The twenty one year old explains how they had no intention of following the advice they had been given regarding love, even though it was coming from a wise man. Housman intentionally gave the adjective “wise” to the man to emphasize two key points. The first key point is to show the importance of his knowledge to the readers, and the second point is that it shows the ignorance of the twenty one year old for not abiding by his guidance. With these two key points come two more regarding why the twenty one year old did not follow the wise man’s words. The first point offers that they underestimated the wise man’s wisdom, and because of this they had to learn through a crucial, heartbreaking experience, “By giving his heart away, the young speaker is now paying the price with pain, sorrow, as he continues to sigh and cry and muse on that sage advice that he now wishes he had followed” (Grimes). The second point infers that they did in fact understand the consequences of not following the wise man, but they were too immature to act upon them.

Freedom

Although the twenty one year old showed readers what ignorance is, the wise man explained to us what freedom is. This poem portrays that whoever is to give their heart away is not free, and this seems to be very true coming from a wise man. However, it does recommend that giving money and precious stones away is the best option to keeping your fancy free. In other words, it is better to give away objects that is not one's heart, because no emotional stability will be lost. This quote “Give crowns and pounds and guineas away...give pearls away and rubies” (Housman, 3-5) helps to explain how money doesn’t buy happiness, and this is inferring that money can buy things that allow the heart to pursue happiness, “The advice to ‘Give crowns and pounds and guineas [away]’ contradicts common knowledge, which dictates that acquiring wealth gives a person the means with which to pursue happiness” (Grimes). This is because giving away money and jewels does not affect your freedom. Giving your heart away, however, does take away your entitlement and can land you in a world full of misery, “One of the simplest and best known poems in A Shropshire Lad, with its obvious backwards glance to Oxford and Moses Jackson, goes so far as to suggest that falling in love is, by definition, bound to lead in lasting unhappiness” (Blocksidge).

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- ↑ The Housman Society

- ↑ Trevor Hold, Parry to Finzi: Twenty English Song-composers, Woodbridge 2002 p.91

- ↑ A performance on You Tube

- ↑ A performance on You Tube

- ↑ Stephen Banfield, Sensibility and English Song, Cambridge University 1988, pp.146, 237

- ↑ LiederNet under “When I was one and twenty”

- ↑ A performance on You Tube

- ↑ A performance on You Tube

- ↑ WorldCat

- ↑ On You Tube

Blocksidge, Martin. A. E. Housman : A Single Life. Sussex Academic Press, 2016. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.mga.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=1234156&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed 1 March 2018. Grimes, Linda Sue. “A. E. Housman's "When I was one-and-Twenty".” Owlcation, Owlcation, 3 Jan. 2018, owlcation.com/humanities/A-E-Housmans-When-I-was-one-and-twenty. Accessed 25 January 2018. Housman, A.E. "When I was One-and-Twenty." The Bedford Introduction to Literature: Reading, Thinking, Writing, 10th ed, edited by Michael Meyer, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2013, pp. 765.

External links

- Explanation: "When I Was One-and-Twenty" from Exploring Poetry, Gale Cengage, 1997. From the Internet archive