Technology during World War I

Technology during World War I (1914–1918) reflected a trend toward industrialism and the application of mass-production methods to weapons and to the technology of warfare in general. This trend began at least fifty years prior to World War I during the American Civil War of 1861–1865,[1] and continued through many smaller conflicts in which soldiers and strategists tested new weapons.

World War I weapons included types standardised and improved over the preceding period, together with some newly developed types using innovative technology and a number of improvised weapons used in trench warfare. Military technology of the time included important innovations in grenades, poison gas, and artillery, along with essentially new weapons such as the submarine, warplane and tank.[2]

One could characterize the earlier years of the First World War as a clash of 20th-century technology with 19th-century military science creating ineffective battles with huge numbers of casualties on both sides. On land, only in the final year of the war did the major armies make effective steps in revolutionizing matters of command and control and tactics to adapt to the modern battlefield and start to harness the myriad new technologies to effective military purposes. Tactical reorganizations (such as shifting the focus of command from the 100+ man company to the 10+ man squad) went hand-in-hand with armored cars, the first submachine guns, and automatic rifles that a single individual soldier could carry and use.

Trench warfare

The new metallurgical and chemical industries created new firepower that briefly simplified defense before new approaches to attack evolved. The application of infantry rifles, rifled artillery and hydraulic recoil mechanisms, zigzag trenches and machine guns made it difficult or nearly impossible to cross defended ground. The hand grenade, long used in crude form, developed rapidly as an aid in attacking trenches. Probably the most important was the introduction of high explosive shells, which dramatically increased the lethality of artillery over the 19th-century equivalents.

Trench warfare led to the development of the concrete pill box, a hardened blockhouse that could be used to deliver machine gun fire. They could be placed across a battlefield with interlocking fields of fire.[3]

Because attacking an entrenched enemy was so difficult, tunnel warfare became a major effort during the war. Once enemy positions were undermined, huge amounts of explosives would be planted and detonated as part preparation for an overland charge. Sensitive listening devices that could detect the sounds of digging were a crucial method of defense against these underground incursions. The British proved especially adept at these tactics, thanks to the skill of their tunnel-digging "sappers" and the sophistication of their listening devices.

Clothing

.jpg)

The British and German armies had already changed from red coat (British army) (1902) or Prussian blue (1910) for field uniforms, to less conspicuous khaki or field gray. Adolphe Messimy, Joseph Gallieni and other French leaders had proposed following suit, but the French army marched to war in their traditional red trousers, and only began receiving the new "horizon blue" ones in 1915.

A type of raincoat for British officers, introduced long before the war, gained fame as the trench coat.

The principal armies entered the war under cloth caps or leather helmets. They hastened to develop new steel helmets, in designs that became icons of their respective countries.

Artillery

In the 19th century, Britain and France exploited the rapid technical developments in artillery to serve a War of Movement. Such weapons served well in the colonial wars of that century, and served Germany very well in the Franco-Prussian War, but trench warfare was more like a siege, and called for siege guns. The German army had already anticipated that a European war might require heavier artillery, hence had a more appropriate mix of sizes. Foundries responded to the actual situation with more heavy products and fewer highly mobile pieces. Germany developed the Paris guns of stupendous size and range. However, the necessarily stupendous muzzle velocity wore out a gun barrel after a few shots requiring a return to the factory for relining, so these weapons served more to frighten and anger urban people than to kill them or devastate their cities.

At the beginning of the war, artillery was often sited in the front line to fire over open sights at enemy infantry. During the war, the following improvements were made:

- The first "box barrage" in history was fired in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in 1915; this was the use of a three- or four-sided curtain of shell-fire to prevent the movement of enemy infantry

- The wire-cutting No. 106 fuze was developed, specifically designed to explode on contact with barbed wire, or the ground before the shell buried itself in mud, and equally effective as an anti-personnel weapon

- The first anti-aircraft guns were devised out of necessity

- Indirect counter-battery fire was developed for the first time

- Artillery sound ranging and flash spotting, for the location and eventual destruction of enemy batteries

- The creeping barrage was perfected

- Factors such as weather, air temperature, and barrel wear could for the first time be accurately measured and taken into account for indirect fire

- Forward observers were used to direct artillery positioned out of direct line of sight from the targets, and sophisticated communications and fire plans were developed

Field artillery entered the war with the idea that each gun should be accompanied by hundreds of shells, and armories ought to have about a thousand on hand for resupply. This proved utterly inadequate when it became commonplace for a gun to sit in one place and fire a hundred shells or more per day for weeks or months on end. To meet the resulting Shell Crisis of 1915, factories were hastily converted from other purposes to make more ammunition. Railways to the front were expanded or built, leaving the question of the last mile. Horses in World War I were the main answer, and their high death rate seriously weakened the Central Powers late in the war. In many places the newly invented trench railways helped. The new motor trucks as yet lacked pneumatic tires, versatile suspension, and other improvements that in later decades would allow them to perform well.

The majority of casualties inflicted during the war were the result of artillery fire.

Poison gas

Chemical weapons were first used systematically in this war. Chemical weapons in World War I included phosgene, tear gas, chlorarsines and mustard gas.

At the beginning of the war, Germany had the most advanced chemical industry in the world, accounting for more than 80% of the world's dye and chemical production. Although the use of poison gas had been banned by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, Germany turned to this industry for what it hoped would be a decisive weapon to break the deadlock of trench warfare. Chlorine gas was first used on the battlefield in April 1915 at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. The unknown gas appeared to be a simple smoke screen, used to hide attacking soldiers, and Allied troops were ordered to the front trenches to repel the expected attack. The gas had a devastating effect, killing many defenders or when the wind direction changed and blew the gas back, many attackers. Because the gas killed the attackers, depending on the wind, a more reliable way had to be made to transmit the gas. It began being delivered in artillery shells.[4] Later, mustard gas, phosgene and other gases were used. Britain and France soon followed suit with their own gas weapons. The first defenses against gas were makeshift, mainly rags soaked in water or urine. Later, relatively effective gas masks were developed, and these greatly reduced the effectiveness of gas as a weapon. Although it sometimes resulted in brief tactical advantages and probably caused over 1,000,000 casualties, gas seemed to have had no significant effect on the course of the war.

Chemical weapons were easily attained, and cheap. Gas was especially effective against troops in trenches and bunkers that protected them from other weapons. Chemical weapons attacked an individual’s respiratory system. The concept of choking easily caused fear in soldiers and the resulting terror affected them psychologically. Because there was such a great fear of chemical weapons it wasn’t uncommon that a soldier would panic and misinterpret symptoms of the common cold as being affected by a poisonous gas.

Command and control

In the early days of the war, generals tried to direct tactics from headquarters many miles from the front, with messages being carried back and forth by couriers on motorcycles. It was soon realized that more immediate methods of communication were needed.

Radio sets of the period were too heavy to carry into battle, and phone lines laid were quickly broken. Runners, flashing lights, and mirrors were often used instead; dogs were also used, though they were only used occasionally as troops tended to adopt them as pets and men would volunteer to go as runners in the dog's place. There were also aircraft (called "contact patrols") that could carry messages between headquarters and forward positions, sometimes dropping their messages without landing.

The new long-range artillery developed just before the war now had to fire at positions it could not see. Typical tactics were to pound the enemy front lines and then stop to let infantry move forward, hoping that the enemy line was broken, though it rarely was. The lifting and then the creeping barrage were developed to keep artillery fire landing directly in front of the infantry "as it advanced". Communications being impossible, the danger was that the barrage would move too fast — losing the protection — or too slowly — holding up the advance.

There were also countermeasures to these artillery tactics: by aiming a counter barrage directly behind an enemy's creeping barrage, one could target the infantry that was following the creeping barrage. Microphones (Sound ranging) were used to triangulate the position of enemy guns and engage in counter-battery fire. Muzzle flashes of guns could also be spotted and used to target enemy artillery.

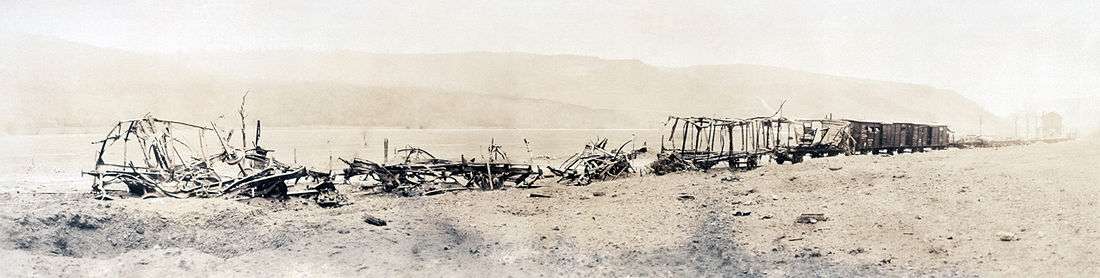

Railways

Railways dominated in this war as in no other. The German strategy was known beforehand by the Allies simply because of the vast marshaling yards on the Belgian border that had no other purpose than to deliver the mobilized German army to its start point. The German mobilization plan was little more than a vast detailed railway timetable. Men and material could get to the front at an unprecedented rate by rail, but trains were vulnerable at the front itself. Thus, armies could only advance at the pace that they could build or rebuild a railway, e.g. the British advance across Sinai. Motorized transport was only extensively used in the last two years of World War I. After the rail head, troops moved the last mile on foot, and guns and supplies were drawn by horses and trench railways. Railways lacked the flexibility of motor transport and this lack of flexibility percolated through into the conduct of the war.

War of attrition

All countries involved in the war applied the full force of industrial mass-production to the manufacture of weapons and ammunition, especially artillery shells. Women on the home-front played a crucial role in this by working in munitions factories. This complete mobilization of a nation's resources, or "total war" meant that not only the armies, but also the economies of the warring nations were in competition.

For a time, in 1914–1915, some hoped that the war could be won through an attrition of materiel—that the enemy's supply of artillery shells could be exhausted in futile exchanges. But production was ramped up on both sides and hopes proved futile. In Britain the Shell Crisis of 1915 brought down the British government, and led to the building of HM Factory, Gretna, a huge munitions factory on the English-Scottish border.

The war of attrition then focused on another resource: human lives. In the Battle of Verdun in particular, German Chief of Staff Erich Von Falkenhayn hoped to "bleed France white" through repeated attacks on this French city.

In the end, the war ended through a combination of attrition (of men and material), advances on the battlefield, arrival of American troops in large numbers, and a breakdown of morale and productivity on the German home-front due to an effective naval blockade of her seaports.

Air warfare

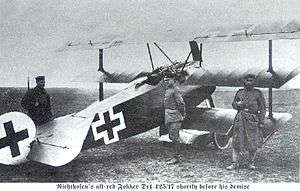

Aviation in World War I started with primitive aircraft, primitively used. Technological progress was swift, leading to ground attack, tactical bombing, and highly publicized, deadly dogfights among aircraft equipped with forward-firing, synchronized machine guns from July 1915 onwards. However, these uses made a lesser impact on the war than more mundane roles in intelligence, sea patrol and especially artillery spotting. Antiaircraft warfare also had its beginnings in this war.

As with most technologies, aircraft and their use underwent many improvements during World War I. As the initial war of movement on the Western Front settled into trench warfare, aerial reconnaissance over the front added to the difficulty of mounting surprise attacks against entrenched and concealed defenders.

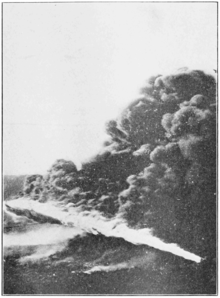

Manned observation balloons floating high above the trenches were used as stationary observation posts, reporting enemy troop positions and directing artillery fire. Balloons commonly had a crew of two, each equipped with parachutes: upon an enemy air attack on the flammable balloon, the crew would jump to safety. At the time, parachutes were too heavy to be used by pilots in aircraft, and smaller versions would not be developed until the end of the war. (In the British case, there arose concerns that they might undermine morale, effectively encouraging cowardice.) Recognized for their value as observer platforms, observation balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by large concentrations of antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft.

While early air spotters were unarmed, they soon began firing at each other with handheld weapons. An arms race commenced, quickly leading to increasingly agile planes equipped with machine guns. A key innovation was the interrupter gear, a Dutch invention[5] that allowed a machine gun to be mounted behind the propeller so the pilot could fire directly ahead, along the plane's flight path.

As the stalemate developed on the ground, with both sides unable to advance even a few miles without a major battle and thousands of casualties, planes became greatly valued for their role gathering intelligence on enemy positions. They also bombed enemy supplies behind the trench lines, in the manner of later attack aircraft. Large planes with a pilot and an observer were used to reconnoiter enemy positions and bomb their supply bases. These large and slow planes made easy targets for enemy fighter planes, who in turn were met by fighter escorts and spectacular aerial dogfights.

German strategic bombing during World War I struck Warsaw, Paris, London and other cities. Germany led the world in Zeppelins, and used these airships to make occasional bombing raids on military targets, London and other British cities, without great effect. Later in the war, Germany introduced long range strategic bombers. Damage was again minor but they forced the British air forces to maintain squadrons of fighters in England to defend against air attack, depriving the British Expeditionary Force of planes, equipment, and personnel badly needed on the Western front.

The Allies made much smaller efforts in bombing the Central Powers.

Tanks

Although the concept of the tank had been suggested as early as the 1890s, few authorities showed interest in them until the trench stalemate of World War I caused reconsideration. The British Royal Navy and French industrialists invented tanks.

In Britain, a landships committee was formed, and teamed with the inventions committee, set out to develop a practical weapon.

Based on the caterpillar track (first invented in 1770 and perfected in the early 1900s) and the four-stroke gasoline powered internal combustion engine (refined in the 1870s), early World War One tanks were fitted with Maxim type guns or Lewis guns, armor plating, and caterpillar tracks configured to allow crossing of an 8-foot-wide (2.4 m) trench.

Early tanks were unreliable, breaking down often. Though at first they terrified the Germans, their use in the engagements of 1917 provided more opportunities for development than actual battle successes. It was also realized that new tactics had to be developed to best make use of this weapon. In particular, planners learned that tanks needed infantry support and massed formations to be effective. Once tanks could be fielded in the hundreds, as in the opening assault of the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, they began to show their potential. German artillerymen quickly learned how to counter them, in small numbers.

Still, reliability was the primary weakness of tanks throughout the remainder of the war. In the Battle of Amiens, a major Entente counteroffensive near the end of the war, British forces went to field with 534 tanks. After several days, only a few were still in commission, with those that suffered mechanical difficulties outnumbering those disabled by enemy fire.

Despite rapidly increasing French production, their numbers remained too small to make more than a modest impact on the progress of the war in 1918. Germany used a few captured enemy tanks, and made a few. Plan 1919 outlined the future use of massive tank formations in great offensives combined with ground attack aircraft.

Regardless of their effects on World War I, tank technology and mechanized warfare had been launched and grew increasingly sophisticated in the years following the war. By World War II, the tank had evolved into a fearsome weapon and restored mobility.[6]

At sea

The years leading up to the war saw the use of improved metallurgical and mechanical techniques to produce larger ships with larger guns and, in reaction, more armor. The launching of HMS Dreadnought (1906) revolutionized battleship construction, leaving many ships obsolete before they were completed. German ambitions brought an Anglo-German naval arms race in which the Imperial German Navy was built up from a small force to the world's most modern and second most powerful. However, even this high-technology navy entered the war with a mix of newer ships and obsolete older ones.

The advantage was in long-range gunnery, and naval battles took place at far greater distances than before. The 1916 Battle of Jutland demonstrated the excellence of German ships and crews, but also showed that the High Seas Fleet was not big enough to challenge openly the British blockade of Germany. It was the only full-scale battle between fleets in the war.

Having the largest surface fleet, the United Kingdom sought to press its advantage. British ships blockaded German ports, hunted down German and Austro-Hungarian ships wherever they might be on the high seas, and supported actions against German colonies. The German surface fleet was largely kept in the North Sea. This situation pushed Germany, in particular, to direct its resources to a new form of naval power: submarines.

Naval mines were deployed in hundreds of thousands, or far greater numbers than in previous wars. Submarines proved surprisingly effective for this purpose. Influence mines were a new development but moored contact mines were the most numerous. They resembled those of the late 19th century, improved so they less often exploded while being laid. The Allies produced enough mines to build the North Sea Mine Barrage to help bottle the Germans into the North Sea, but it was too late to make much difference.

Submarines

World War I was the first conflict in which submarines were a serious weapon of war. In the years shortly before the war, the relatively sophisticated propulsion system of diesel power while surfaced and battery power while submerged was introduced. Their armament had similarly improved, but few were in service. Germany had already increased production, and quickly built up its U-boat fleet, both for action against British warships and for a counterblockade of the British Isles. 360 were eventually built. The resulting U-boat Campaign (World War I) destroyed more enemy warships than the High Seas Fleet had, and hampered British war supplies as the more expensive surface fleet had not.

The United Kingdom relied heavily on imports to feed its population and supply its war industry, and the German Navy hoped to blockade and starve Britain using U-boats to attack merchant ships. Lieutenant Otto Weddigen remarked of the second submarine attack of the Great War:

| “ | How much they feared our submarines and how wide was the agitation caused by good little U-9 is shown by the English reports that a whole flotilla of German submarines had attacked the cruisers and that this flotilla had approached under cover of the flag of Holland. These reports were absolutely untrue. U-9 was the only submarine on deck, and she flew the flag she still flies – the German naval ensign. | ” |

Submarines soon came under persecution by submarine chasers and other small warships using hastily devised anti-submarine weapons. They could not impose an effective blockade while acting under the restrictions of the prize rules and international law of the sea. They resorted to unrestricted submarine warfare, which cost Germany public sympathy in neutral countries and was a factor contributing to the American entry into World War I.

This struggle between German submarines and British counter measures became known as the "First Battle of the Atlantic". As German submarines became more numerous and effective, the British sought ways to protect their merchant ships. "Q-ships", attack vessels disguised as civilian ships, were one early strategy.

Consolidating merchant ships into convoys protected by one or more armed navy vessels was adopted later in the war. There was initially a great deal of debate about this approach, out of fear that it would provide German U-boats with a wealth of convenient targets. Thanks to the development of active and passive sonar devices,[7] coupled with increasingly deadly anti-submarine weapons, the convoy system reduced British losses to U-boats to a small fraction of their former level.

Mobility

Between late 1914 and early 1918, the Western Front hardly moved. The beginning of the end for Germany was a huge German advance. In 1917, when Russia surrendered after the October Revolution, Germany was able to move many troops to the Western Front and launch Operation Michael. Using new stormtrooper tactics developed by Oskar von Hutier, the Germans pushed forward some tens of kilometers from March to July 1918. These offensives showed that machine guns, barbed wire and trenches were not the only obstacles to mobile warfare.

In the Battle of Amiens of August 1918, the Triple Entente forces began a counterattack that would be called the "Hundred Days Offensive". The Australian and Canadian divisions that spearheaded the attack managed to advance 13 kilometers on the first day alone. These battles marked the end of trench warfare on the Western Front and a return to mobile warfare. The sort of unit that now began to emerge combined cyclist infantry and machine guns mounted on motor cycle sidecars. These motor machine gun units had originated in 1915 .

The Hindenburg Line fell to the Allies and the Canal du Nord was crossed. In Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm was told Germany had lost, and must now surrender. Advances continued but political developments inside Germany compelled Germany to sign an armistice on November 11, 1918.

The war was over, but a new mobility-driven form of warfare was beginning to emerge; one that would be mastered by the defeated Germans and deployed in 1939 as their blitzkrieg, or "lightning warfare", embodying all they had learned in 1918.

Small arms

Infantry weapons for major powers were mainly bolt action rifles, capable of firing ten or more rounds per minute. German soldiers carried Gewehr 98 rifle in 8mm mauser, while the British carried the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle.[8] Rifles with telescopic sights were used by snipers, and were first used by the Germans.[9]

Machine guns were also used by large powers; both sides used the Maxim gun, a fully automatic belt-fed weapon, capable of long-term sustain used provided it was supplied to adequate amounts of ammunition and cooling water, and its French counterpart, the Hotchkiss M1914 machine gun.[10] Their use in defense, combined with barbed wire obstacles, converted the expected mobile battlefield to a static one. The machine gun was useful in stationary battle but was not practical for easy movement through battlefields, and therefore forced soldiers to face enemy machine guns without machine guns of their own.

Before the war, the French Army studied the question of a light machine gun but had made none for use. At the start of hostilities, France quickly turned an existing prototype (the "CS" for Chauchat and Sutter) into the lightweight Chauchat M1915 automatic rifle with a high rate of fire. Besides its use by the French, the first American units to arrive in France used it in 1917 and 1918. Hastily mass-manufactured under desperate wartime pressures, the weapon developed a reputation for unreliability.[11]

Seeing the potential of such a weapon, the British Army adopted the American-designed Lewis gun chambered in .303 British. The Lewis gun was the first true light machine gun that could in theory be operated by one man, though in practice the bulky ammo pans required an entire section of men to keep the gun operating.[12] The Lewis Gun was also used for marching fire, notably by the Australian Corps in the July 1918 Battle of Hamel.[11][13] To serve the same purpose, the German Army adopted the MG08/15 which was impractically heavy at 48.5 pounds (22 kg) counting the water for cooling and one magazine holding 100 rounds.[13] In 1918 the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) was introduced in the US Army, the weapon was an "automatic rifle" and like the Chauchat was designed with the concept of walking fire in mind.[14] The tactic was to be employed under conditions of limited field of fire and poor visibility such as advancing through woods.[15][16]

Some of the first submachine guns was widespread use near the end of the war such as the MP-18.

Grenades

Grenades proved to be effective weapons in the trenches. When the war started, grenades were few and poor. Hand grenades were used and improved throughout the war. Contact fuzes became less common, replaced by time fuzes.

The British entered the war with the long-handled impact detonating "Grenade, Hand No 1".[17] This was replaced by the No. 15 "Ball Grenade" to partially overcome some of its inadequacies. An improvised hand grenade was developed in Australia for use by ANZAC troops called the Double Cylinder "jam tin" which consisted of a tin filled with dynamite or guncotton, packed round with scrap metal or stones. To ignite, at the top of the tin there was a Bickford safety fuse connecting the detonator, which was lit by either the user, or a second person.[17] The "Mills bomb" (Grenade, Hand No. 5) was introduced in 1915 and would serve in its basic form in the British Army until the 1970s. Its improved fusing system relied on the soldier removing a pin and while holding down a lever on the side of the grenade. When the grenade was thrown the safety lever would automatically release, igniting the grenades internal fuse which would burn down until the grenade detonated. The French would use the F1 defensive grenade.

The major grenades used in the beginning by the German Army were the impact-detonating "discus" or "oyster shell" bomb and the Mod 1913 black powder kugelhandgranate with a friction-ignited time fuse.[17] During the war Germany developed the much more effective Model 24 grenade or "potato masher" whose variants remained in use for decades.

Hand grenades were not the only attempt at projectile explosives for infantry. A rifle grenade was brought into the trenches to attack the enemy from a greater distance. The Hales rifle grenade got little attention from the British Army before the war began but, during the war, Germany showed great interest in this weapon. The resulting casualties for the Allies caused Britain to search for a new defense.[18]

The Stokes mortar, a lightweight and very portable trench mortar with short tube and capable of indirect fire, was rapidly developed and widely imitated.[19] Mechanical bomb throwers of lesser range were used in a similar fashion to fire upon the enemy from a safe distance within the trench.

The Sauterelle was a grenade launching Crossbow used before the Stokes morter by French and British troops.

Flame throwers

The Imperial German Army deployed flame throwers (Flammenwerfer) on the Western Front attempting to flush out French or British soldiers from their trenches. Introduced in 1915, it was used with greatest effect during the Hooge battle of the Western Front on 30 July 1915. The German Army had two main types of flame throwers during the Great War: a small single person version called the Kleinflammenwerfer and a larger crew served configuration called the Grossflammenwerfer. In the latter, one soldier carried the fuel tank while another aimed the nozzle. Both the large and smaller versions of the flame-thrower were of limited use because their short range left the operator(s) exposed to small arms fire.

See also

- British weapons of World War I

- List of German weapons of World War I

References

- ↑

Compare: Boot, Max (2006). "The Consequences of the Industrial Revolution". War Made New: Weapons, Warriors, and the Making of the Modern World (reprint ed.). New York: Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 9781101216835. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

The First Industrial Revolution transformed warfare between the end of the Crimean War (1856) and the start of World War I (1914)

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (1998) The Great War: 1914-18. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; p. 11

- ↑ March, F. A.; Beamish, R. J. (1919), History of the World War: An Authentic Narrative of the World's Greatest War, Leslie-Judge

- ↑ Chemical weapons in World War I

- ↑ http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1369.htm

- ↑ Raudzens 1990, pp. 421–426

- ↑ Hartcup 1988, pp. 129, 130, 140

- ↑ Bull, Stephen (2002) World War 1 Trench Warfare; (1): 1914-16. Oxford: Osprey Publishing; pp. 9-10

- ↑ Ellis, John (1989) Eye Deep in Hell: trench warfare in World War 1. London: Pantheon Books, Random House; p. 69

- ↑ Bull, Stephen (2002) World War 1 Trench Warfare; (1): 1914-16. Oxford: Osprey Publishing; pp. 11-12

- 1 2 Bull, Stephen; Hook, Adam (2002). World War I Trench Warfare (1916–1918). Elite. 84 (3 ed.). Osprey. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-84176-198-2.

- ↑ P. Griffiths 1994 Battle Tactics of the Western Front p130

- 1 2 Sheffield, G.D. (2007). War on the Western Front. Osprey. p. 250. ISBN 1-84603-210-5.

- ↑ Persons, William Ernest (1920). Military science and tactics. 2. p. 280.

- ↑ Blain, W.A. (November–December 1921). "Does the Present Automatic Rifle Meet the Needs of the Rifleman?". The Military Engineer. Society of American Military Engineers. 12–13: 534–535.

- ↑ Landing-Force Manual: United States Navy. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1921. p. 447.

- 1 2 3 Bull, Stephen (2002) World War 1 Trench Warfare; (1): 1914-16. Oxford: Osprey Publishing; p. 27

- ↑ Bull, Stephen (2002) World War 1 Trench Warfare; (1): 1914-16. Oxford: Osprey Publishing; p. 29

- ↑ Duffy, Michael (2000-07) "Safe Surf". http://www.firstworldwar.com/weaponry/mortars.htm

External links

- Johnson, Jeffrey: Science and Technology , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Historical film documents on technology during World War I at www.europeanfilmgateway.eu.

- Zabecki, David T.: Military Developments of World War I , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane: Weapons , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Pöhlmann, Markus: Close Combat Weapons , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Watanabe, Nathan: Hand Grenade , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Storz, Dieter: Rifles , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Cornish, Paul: Flamethrower , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Storz, Dieter: Artillery , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Cornish, Paul: Machine Gun , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.