Japanese mathematics

Japanese mathematics (和算 wasan) denotes a distinct kind of mathematics which was developed in Japan during the Edo period (1603–1867). The term wasan, from wa ("Japanese") and san ("calculation"), was coined in the 1870s[1] and employed to distinguish native Japanese mathematical theory from Western mathematics (洋算 yōsan).[2]

In the history of mathematics, the development of wasan falls outside the Western realms of people, propositions and alternate solutions. At the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912), Japan and its people opened themselves to the West. Japanese scholars adopted Western mathematical technique, and this led to a decline of interest in the ideas used in wasan.

History

This mathematical schema evolved during a period when Japan's people were isolated from European influences. Kambei Mori is the first Japanese mathematician noted in history.[3] Kambei is known as a teacher of Japanese mathematics; and among his most prominent students were Yoshida Shichibei Kōyū, Imamura Chishō, and Takahara Kisshu. These students came to be known to their contemporaries as "the Three Arithmeticians".[4]

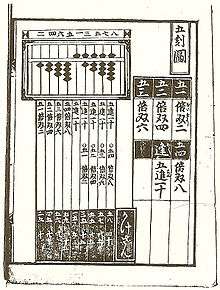

Yoshida was the author of the oldest extant Japanese mathematical text. The 1627 work was named Jinkōki. The work dealt with the subject of soroban arithmetic, including square and cube root operations.[5] Yoshida's book significantly inspired a new generation of mathematicians, and redefined the Japanese perception of educational enlightenment, which was defined in the Seventeen Article Constitution as "the product of earnest meditation".[6]

Seki Takakazu founded enri(円理:circle principles), a mathematical system with the same purpose as calculus at a similar time to calculus's development in Europe; but Seki's investigations did not proceed from conventionally shared foundations.[7]

Select mathematicians

The following list encompasses mathematicians whose work was derived from wasan.

- Kambei Mori (early 17th century)

- Yoshida Mitsuyoshi (1598–1672)

- Seki Takakazu (1642–1708)

- Takebe Kenkō (1664–1739)

- Matsunaga Ryohitsu (fl. 1718-1749)[8]

- Kurushima Kinai (d. 1757)

- Arima Raido (1714–1783)[9]

- Fujita Sadasuke (1734-1807)[10]

- Ajima Naonobu (1739–1783)

- Aida Yasuaki (1747–1817)

- Sakabe Kōhan (1759–1824)

- Fujita Kagen (1765–1821)[10]

- Hasegawa Ken (c. 1783-1838)[9]

- Wada Nei (1787–1840)

- Shiraishi Chochu (1796–1862)[11]

- Koide Shuke (1797–1865)[9]

- Omura Isshu (1824–1871)[9]

See also

- Japanese theorem for cyclic polygons

- Japanese theorem for cyclic quadrilaterals

- Sangaku, the custom of presenting mathematical problems, carved in wood tablets, to the public in Shinto shrines

- Soroban, a Japanese abacus

- Category:Japanese mathematicians

Notes

- ↑ Selin, Helaine. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, p. 641. , p. 641, at Google Books

- ↑ Smith, David et al. (1914). A History of Japanese Mathematics, p. 1 n2., p. 1, at Google Books

- ↑ Campbell, Douglas et al. (1984). Mathematics: People, Problems, Results, p. 48.

- ↑ Smith, p. 35. , p. 35, at Google Books

- ↑ Restivo, Sal P. (1984). Mathematics in Society and History, p. 56., p. 56, at Google Books

- ↑ Strayer, Robert (2000). Bedford/st.Martins. p. 7. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Smith, pp. 91–127., p. 91, at Google Books

- ↑ Smith, pp. 104, 158, 180., p. 104, at Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 List of Japanese mathematicians -- Clark University, Dept. of Mathematics and Computer Science

- 1 2 Fukagawa, Hidetoshi et al. (2008). Sacred Mathematics: Japanese Temple Geometry, p. 24., p. 24, at Google Books

- ↑ Smith, p. 233., p. 233, at Google Books

References

- Campbell, Douglas M. and John C. Iggins. (1984). Mathematics: People, Problems, Results. Belmont, California: Warsworth International. ISBN 9780534032005; ISBN 9780534032012; ISBN 9780534028794; OCLC 300429874

- Endō Toshisada (1896). History of mathematics in Japan (日本數學史史 Dai Nihon sūgakush). Tōkyō: _____. OCLC 122770600

- Fukagawa, Hidetoshi, and Dan Pedoe. (1989). Japanese temple geometry problems = Sangaku. Winnipeg: Charles Babbage. ISBN 9780919611214; OCLC 474564475

- __________ and Dan Pedoe. (1991) How to resolve Japanese temple geometry problems? (日本の幾何ー何題解けますか? Nihon no kika nan dai tokemasu ka) Tōkyō : Mori Kitashuppan. ISBN 9784627015302; OCLC 47500620

- __________ and Tony Rothman. (2008). Sacred Mathematics: Japanese Temple Geometry. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069112745X; OCLC 181142099

- Horiuchi, Annick. (1994). Les Mathematiques Japonaises a L'Epoque d'Edo (1600–1868): Une Etude des Travaux de Seki Takakazu (?-1708) et de Takebe Katahiro (1664–1739). Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin. ISBN 9782711612130; OCLC 318334322

- __________. (1998). "Les mathématiques peuvent-elles n'être que pur divertissement? Une analyse des tablettes votives de mathématiques à l'époque d'Edo." Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, volume 20, pp. 135–156.

- Kobayashi, Tatsuhiko. (2002) "What kind of mathematics and terminology was transmitted into 18th-century Japan from China?", Historia Scientiarum, Vol.12, No.1.

- Kobayashi, Tatsuhiko. Trigonometry and Its Acceptance in the 18th-19th Centuries Japan.

- Morimoto, Mitsuo. "Infinite series in Japanese Mathematics of the 18th Century".

- Morimoto, Mitsuo. "A Chinese Root of Japanese Traditional Mathematics – Wasan"

- Ogawa, Tsukane. "A Review of the History of Japanese Mathematics". Revue d'histoire des mathématiques 7, fascicule 1 (2001), 137-155.

- Restivo, Sal P. (1992). Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 9780792317654; OCLC 25709270

- Selin, Helaine. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Dordrecht: Kluwer/Springer. ISBN 9780792340669; OCLC 186451909

- David Eugene Smith and Yoshio Mikami. (1914). A History of Japanese Mathematics. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. OCLC 1515528; see online, multi-formatted, full-text book at archive.org