WAVES

The United States Naval Reserve (Women's Reserve), better known as the WAVES for the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, was the World War II women's branch of the United States Naval Reserve. It was established on 21 July 1942 by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 30 July 1942. This authorized the U.S. Navy to accept women into the Naval Reserve as commissioned officers and at the enlisted level, effective for the duration of the war plus six months. The purpose of the law was to release officers and men for sea duty and replace them with women in shore establishments. Mildred H. McAfee became the first director of the WAVES. She was commissioned a lieutenant commander on 3 August 1942, and later promoted to commander and then to captain. McAfee, on leave as President of Wellesley College, was an experienced educator and highly respected in her field.

The notion of women serving in the Navy was not widely supported in the Congress or by the Navy, although some members did support the need for uniformed women during World War II. Public Law 689, allowing women to serve in the Navy, was due in large measure to the efforts of the Navy's Women's Advisory Council, Margaret Chung, and Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady of the United States.

The eligible age for officer candidates was between 20 and 49, with a college degree, or two years of college and two years of equivalent professional or business experience. For enlisted, the eligible age was between 20 and 35, with a high school or business diploma, or equivalent experience. The WAVES were primarily white, but 74 African-American women did eventually serve. The Navy's indoctrination of most WAVE officer candidates took place at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. Specialized training for officers was held on several college campuses and at various naval facilities. Most enlisted members received recruit training at Hunter College, in the Bronx, a borough of New York City. After recruit training, some women attended specialized training courses on college campuses and at naval facilities.

The WAVES served at 900 stations in the United States. The territory of Hawaii was the only overseas station staffed with WAVES. Many officers entered fields previously held by men, such as doctors and engineers. Enlisted women served in jobs from administrative and clerical to parachute riggers. The WAVES' peak strength was 86,291 members; upon their demobilization, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, Fleet Admiral Ernest King, and Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz all commended the WAVES for their contributions to the war effort.

Background

In May 1941, Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill in the U.S. Congress to establish a Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). As the word auxiliary suggests, women would serve not in the Army, but with it, and would be denied the benefits of their male counterparts. Opposition delayed the passage of the bill until May 1942.[1] At the same time, the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics believed the Navy would eventually need women in uniform, and had asked the Bureau of Naval Personnel, headed by Rear Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, to propose legislation, as it had done during World War I, authorizing women to serve in the Navy under the Yeoman (F) classification. Nimitz was not considered an advocate for bringing women into the Navy, and the head of the U.S. Naval Reserve expressed the view that the Civil Service would be able to supply any extra personnel that might be needed.[2]

On 9 December 1941, Representative Rogers telephoned Nimitz and asked him whether the Navy was interested in some sort of women's auxiliary corps. In her book, Lady in the Navy, Joy Bright Hancock quotes his reply: "I advised Mrs. Rogers that at the present time I saw no great need for such a bill".[3] Nevertheless, within days Nimitz was in touch with all Navy Department bureaus asking them to assess their needs for an equivalent to the WAAC. With few exceptions, the responses were negative. Yet, Congressional inquiries continued to increase about the Navy's plan for women.[4]

Then on 2 January 1942, the Bureau of Personnel, in an about-face, recommended to the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, that Congress be asked to authorize a women's organization.[5] The following month, Knox recommended a women's branch as part of the Naval Reserve. The director of the Bureau of the Budget opposed his idea, but would agree to legislation similar to the WAAC bill – where women were with, but not in the Navy. This was unacceptable to Knox. Still, the Bureau of Aeronautics continued to believe there was a place for women in the Navy, and appealed to an influential friend of naval aviation, Margaret Chung.[6] In Crossed Currents, the authors describe Chung and her involvement:

Dr. Margaret Chung of San Francisco, a physician and surgeon, had a long time interest in aviation, particularly naval aviation. She had many naval aviation friends who referred to themselves as "sons of Mom Chung". Having learned of the stalemate, she asked one of these, Representative Melvin Maas of Minnesota, who had served in the aviation branch of the U.S. Marine Corps in World War I, to introduce legislation independently of the Navy. On 18 March 1942 he did just that.[7]

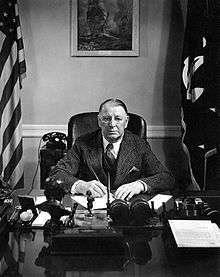

Maas's House bill was essentially the same as the Knox proposal, which would make a women's branch part of the Naval Reserve. At the same time, Senator Raymond E. Willis of Indiana introduced a similar bill in the Senate. On 16 April 1942, the House Naval Affairs Committee reported favorably on the bill. It was passed by the House the same day and sent to the Senate.[8] The Senate Naval Affairs Committee was opposed to the bill, especially its chairman – Senator David I. Walsh of Massachusetts. He did not want women in the Navy because it "would tend to break-up American homes and would be a step backwards in the progress of civilization."[9] The Senate committee eventually proposed a naval version of the WAAC, and the president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, approved it. But Knox asked the president to reconsider.[6]

Creation of the program

.jpg)

By mid-1942, it was apparent to the Navy that women would eventually be allowed to serve. The quandary for the organization was how to administer a woman's program while fashioning it to their own liking.[8] The Navy asked women educators for assistance, first contacting Dr. Virginia C. Gildersleeve, dean of Barnard College. She suggested that Professor Elizabeth Reynard, also of Barnard, become a special assistant to Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, Chief of Naval Personnel. Reynard was well known for the academic work she had done on women in the workplace. Her first-rate performance as Jacobs' assistant silenced any fears the Navy may have had about women educators. Reynard quickly formed the Women's Advisory Council to meet with Navy officials. Gildersleeve became the chairperson. Because of her efforts, eight prominent women agreed to serve on the council. They included:

- Dr. Meta Glass of Sweet Briar College

- Dr. Lillian Gilbreth, a national authority on efficiency in the workplace

- Dr. Ada Comstock, President of Radcliffe College

- Dean Alice Crocker Lloyd of the University of Michigan

- Mrs. Malbone Graham, a noted lecturer from the West Coast

- Marie Rogers Gates, the wife of Thomas Sovereign Gates, president of the University of Pennsylvania

- Harriet Elliott, dean of women at the University of North Carolina

- Dean Elliott, who later resigned and was replaced by Dr. Alice Baldwin, dean of women at Duke University.[10]

The council knew the success of a fledging program would depend on the woman chosen to lead it. A prospective candidate would need to possess proven managerial skills, command respect, and have an ability to get along well with others. Their recommendation was Mildred H. McAfee, president of Wellesley College, as the future director.[10] The Navy agreed. The task of convincing McAfee to accept and persuading the Wellesley Board of Trustees to release her was difficult, but successful.[11] Mildred McAfee was an experienced and respected academician, whose background would provide a measure of creditability to the idea of women serving in the Navy.[12]

Reynard, who was later commissioned a lieutenant in the WAVES, was tasked with selecting a name. She explained:[12][13]

I realized there were two letters that had to be in it: W for women and V for volunteer, because the Navy wants to make it clear that this is a voluntary service and not a drafted service. So, I played with those two letters and the idea of the sea and finally came up with Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service – WAVES. I figured the word Emergency would comfort the older admirals because it implies that we're only a temporary crisis and won't be around for keeps.[14]

Then on 25 May 1942, the Senate Naval Affairs Committee recommended to the president that the legislation to create a women's reserve correspond with the WAAC legislation. The president called on Knox to reconsider his position, but Knox, who did not favor the WAAC concept, stood his ground. Council members Gildersleeve and Elliott each took it on themselves to write the president's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, explaining their objections to the WAAC legislation. Eleanor showed Elliott's letter to her husband, the president, and she sent Gildersleeve's letter on to the Undersecretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal, a former naval aviator. Within days Forrestal replied, saying that Secretary Knox had asked the president to reconsider. Then on 16 June 1942, Knox informed Rear Admiral Jacobs that the president had given him authority to proceed with a women's reserve.[15]

Days later, Knox informed Senator Walsh of the president's decision, and on 24 June the Senate Naval Affairs Committee reported favorably on the bill. By 21 July, the bill had passed both houses of Congress and been sent to the president, who signed it on 30 July as Public Law 689. This created the Women's branch of the Navy reserve, as amended under Title V of the U.S. Naval Reserve Act of 1938.[15] Less than a year later, on 1 July 1943, Congress refashioned the WAAC into the Women's Army Corps (WAC), which provided its members with similar military status as the WAVES.[1]

This law was enacted to free up officers and men for duty at sea, and to replace them with WAVES at shore stations on the home front. Women could now serve in the Navy as an officer or at an enlisted level, with a rank or rate consistent with that of the regular Navy. Volunteers could only serve for the duration of the war plus six months, and only in the continental United States. They were prohibited from boarding naval ships or combat aircraft, and were without command authority, except within the women's branch.[16]

Mildred H. McAfee became the first director of the WAVES. She was commissioned a lieutenant commander on 3 August 1942, and was the first woman officer commissioned in the U.S. Naval Reserve.[13] McAfee was later promoted to the rank of captain.[17] In More Than a Uniform, Winifred Quick Collins (a former WAVE officer) described Director McAfee as a born diplomat, handling difficult matters with finesse.[18] She also said McAfee played important decision-making roles in the WAVES' treatment compared to the men and in their assignments, housing conditions, and supervision and discipline standards.[19]

In establishing the office of the director, the Bureau of Personnel did not define the responsibilities of the office, nor establish clear lines of authority. "... Lieutenant Commander McAfee was simply told by the bureau that she was to 'run' the women's reserve and she was to go directly to the Chief of Naval Personnel for answers to her questions. Unfortunately, the decision was not made known to the operating divisions of the bureau."[20] No plans existed to help guide her; in fact, no planning had been done, by anyone, in anticipation of the Women's Reserve Act. For insights, McAfee turned to Joy Bright Hancock, a Navy Yeoman (F) during World War I, and a career writer and editor for the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics. She was asked to examine the procedures employed by the Women's Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force, which had a complement of 6,000 members. Many of her findings were later used by the WAVES.[13]

By August and September 1942, another 108 women were commissioned as officers in the Women's Reserve, selected for their educational and business backgrounds. They were drawn to the program by the good standing of McAfee and the Advisory Council. Four of these women would later become the directors of the WAVES and the director of the SPARS (U.S. Coast Guard Women's Reserve). The new officers began their work routine with no grasp of Navy traditions, or training in the operating methods in use, resulting in some difficulties. On 16 September 1942, the Bureau of Personnel issued a memorandum for the organization of the Women's Reserve specifying that the director would administer the program, set policies, and coordinate work within the bureau's operating divisions. Soon, McAfee was able to bring together a capable staff, building a sound internal organization.[21]

Recruiting

_Harriet_Ida_Pickens_and_Ens._Frances_Wills%2C_first_Negro_Waves_to_be_commissioned._They_were_members_of_the_fin_-_NARA_-_520670.jpg)

The WAVE officers were first assigned to recruiting stations in the different U.S. naval districts, later they were joined by enlisted personnel with recruiter training. The primary sources of publicity used were the radio, newspapers, posters, brochures, and personal contacts. The focus of their advertising campaign was patriotism and the need for women. McAfee demanded good taste in all the advertising. At the end of 1942, there were 770 officers and 3,109 enlisted women in the WAVES. By 3 July 1945 their ranks had risen to 86,291, which included 8,475 officers, 73,816 enlisted, and about 4,000 in training.[22]

The age for officer candidates was between 20 and 49, with a college degree, or two years of college and two years of equivalent professional or business experience. The enlisted age requirements were between 20 and 35, with a high school or business diploma, or equivalent experience. United States citizenship was required in each case. The WAVES were primarily white, and middle class, and they represented every state in the country. New York, California, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts and Ohio led the way.[23]

The legislation that established the WAVES contained nothing about the inclusion or exclusion of people of color, but the Navy Department decided that it should be exclusively white.[24] Knox said that black WAVES would be enlisted over his dead body. So it proved. After his death on 28 April 1944, his successor, Forrestal, immediately moved to reform the Navy's racial policies. He submitted a proposal to accept WAVES on an integrated basis to the president on 28 July 1944. Aware that 1944 was an election year, Forrestal attempted to compromise by offering segregated living quarters and mess facilities, but Roosevelt decided to hold it up until after the election on 7 November. His opponent, Thomas E. Dewey, made an election issue of it when he criticised the administration for discriminating against black women in a speech in Chicago. Roosevelt immediately issued the order to accept African-American women on 19 October 1944.[25]

The first two African-American officers were Lieutenant Harriet Ida Pickens and Ensign Frances Wills. Both graduated from Smith College and were commissioned in the WAVES on 21 December. Enlistment of African-American women commenced the following week. The promise of segregated quarters could not be maintained; each recruit company contained 250 women, and there were insufficient black recruits to form an all-black company. It looked like this would become yet another excuse to exclude black women, but McAfee appealed to Forrestal, and he dropped the segregation requirement. Some 72 African American WAVES were trained at Hunter College Naval Training School by July 1945. While training was integrated, black WAVES were restricted somewhat in specialty assignments and a certain amount of separate quartering within integrated barracks prevailed at some duty stations.[25] Those that remained in the Navy after the war were employed without discrimination; but there were only five left by September 1946.[26]

Uniforms

.jpg)

The WAVES looked professional and attractive in stylish uniforms created especially for them.[27] The noted New York fashion house of Mainbocher designed the uniforms. Their design services were secured, without cost, through the efforts of Mrs. James V. Forrestal, wife of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[28] The winter uniform was made from navy blue wool, worn with a white shirt and dark blue tie. The jacket was single breasted and unbelted, with a six-gored skirt. Included were black Oxford shoes and cap and plain black pumps; a brimmed hat; black gloves; black leather purse, and rain and winter coats. The summer uniform was the same as the winter uniform, however, it was lighter in weight, made of white material and worn with white shoes.[29] Later, a gray and white striped, seersucker work uniform for summer was added, along with the wearing of slacks and dungarees when appropriate.[30]

Training

Training of officers

The Navy chose Smith College at Northampton, Massachusetts, as the site for the training of WAVE officers. The facility offered much of what the Navy needed, and a college setting provided the proper training ground.[31] The nickname for Smith was the USS Northampton.[32] Captain H. W. Underwood, USN (Retired), was recalled to active duty on 13 August 1942; then ordered to serve as the commanding officer of the United States Naval Reserve Midshipmen's School at Smith College. Underwood had a distinguished naval career and received the Navy Cross during World War I.[33] In Lady in the Navy, Joy Bright Hancock described Underwood as intelligent, enthusiastic, and good humored, and serious of purpose.[34]

Underwood and his staff quickly developed the indoctrination curriculum that would hasten the transformation of civilian women into naval officers. The curriculum included: organization; personnel; naval history and law; ships and aircraft; naval communications and correspondence. There would be two-months' of intensive training, yet too short a period to produce an overall naval officer. Still, the rationale was to teach the fundamental traditions of life and work in the naval service, focusing on administrative procedures. It was the type of work that most officers would eventually be doing. The curriculum did not change much over the life of the training program.[35]

Following their two-months' of training, the midshipmen were commissioned as ensigns or lieutenants (junior grade) in the U.S. Naval Reserve. The school closed in December 1944, after accepting 10,181 women and graduating 9,477 of them. It also trained 203 SPARS and 295 women of the United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve. Many of these commissioned officers were sent to specialized schools for training in communications, supply, the Japanese language, meteorology, and engineering. The courses of study were held on the college campuses of Mount Holyoke College; Harvard University; University of Colorado; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of California; and the University of Chicago. The Bureau of Ordnance also opened its schools to WAVE officers, where some of them studied aviation ordnance. Other officers attended the Naval Technical Training Command School, while others trained to become aviation instructors. Unlike the training on the college campuses, the training offered at these facilities was coeducational.[36]

Training of enlisted

The campuses of Oklahoma A&M College, Indiana University, and the University of Wisconsin were selected by the Navy for both recruit and specialized training of enlisted WAVES. The training for the initial groups of enlisted women began on 9 October 1942. It soon became clear, however, these arrangements were unsuitable for recruit training, because of dispersed training facilities, inexperienced instructors, and the lack of esprit de corps. As a result, the Navy quickly made the decision to establish one recruit-training center on the campus of the Iowa State Teachers College. The specialized training remained at the original locations.[37]

Iowa State Teachers College, Cedar Falls, Iowa, became the new basic training center for enlisted WAVES. (The school's original assignment was the training of yeomen.) Captain Randall Davis was named commanding officer. He arrived on 1 December 1942, two weeks before the first class of 1,050 enlisted recruits were to start their five-weeks of basic training. The recruit training routine began each weekday with Reveille at 5:30 or 6:00 a.m.; breakfast at 6:30 a.m.; classes and drill for four hours before lunch, and classes and drill for another four hours in the afternoon. This was followed by an hour of free time, dinner, and two hours of study or instruction, lights out at 10:00 p.m. The Captain's Inspection was on Saturday morning, then free time until taps. On Sunday, Reveille was at 7:00 a.m., with breakfast at 7:30 a.m. Trainees then attended church services, followed by free time until 7:30 p.m., when study hours began. Recruits received immunization shots and were given a series of job aptitude tests. The first class was to graduate in January 1943. But on 30 December 1942, the Navy announced that recruits in training and all future recruits would be trained at Hunter College in the Bronx, a borough of the City of New York. The change came because of the Navy's reassessment of how many more women would be needed, and the kinds of work they would be effective in doing. Iowa State Teachers College would return to training yeomen.[38]

Hunter College became the main recruit training center for enlisted WAVES; chosen because of its space; location; ease of transportation, and the willingness of the college to make its facilities available. Captain William F. Amsden, also a recipient of the Navy Cross in World War I, was named the commanding officer. On 8 February 1943, the college was commissioned the U.S. Naval Training Center, the Bronx, and became known as the USS Hunter.[39] Nine days later, approximately 2,000 recruits began their six-weeks of training.[40] The training objectives were meant to be similar to those of the boot camp for men. In Lady in the Navy, Hancock described the training of the recruits in this way: "Each recruit went through a balanced training program. She was instructed in Navy ranks and rates; ships and aircraft of the fleet; naval traditions and customs; and of course, naval history. Physical training and fitness were stressed. As the women marched in platoons to classes, medical examinations, and drills, their approach was signaled by singing, their voices providing the cadence for marching feet."[41] Between 17 February 1943 and 10 October 1945, some 80,936 WAVES, 1,844 SPARS, and 3,190 women Marines completed the training course. The SPARS and Marine reservists used the Navy's training center until the summer of 1943, at which time they established their own training centers.[40]

Of the graduating classes at Hunter, 83% went on to specialized schools to train as yeomen; radiomen; storekeepers, and cooks and bakers. The enlisted WAVES trained at Georgia State College for Women in Milledgeville; Burdett College in Boston, and Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. The Bureaus of Aeronautics and Medicine opened their doors to the enlisted WAVES. The training in aeronautics took place at naval air stations and training centers; the training for medical technicians was held at the National Medical and Great Lakes Training Centers. Unlike the training on the college campuses, the training at these facilities was coeducational.[40]

Assignments

The WAVES served in 900 shore stations in the continental United States. Initially, they were prohibited from serving in commands afloat and outside of the country.[30] But in September 1944, the Congress amended the law allowing the WAVES to volunteer for service in the territories of Alaska and Hawaii.[42] Hawaii became the only overseas station staffed with the WAVES on a permanent basis.[43] By the end of the war, 18% of the naval personnel assigned to shore stations were women. The officers served in many professional capacities, including doctors; attorneys; engineers and mathematicians, and chaplains. One WAVE mathematician, Grace Hopper, was assigned to Harvard University to work on the computation project with the Mark I computer. Another became the only female nautical engineer in the entire U.S. Navy. The enlisted WAVES worked in jobs such as aviation machinist; aviation metalsmith; parachute rigger; control tower operator; radiomen; yeoman; statistician; administration; personnel, and health care.[44] Although some of the enlisted women had the opportunity to work in fields previously held by the men, most of them worked in a secretarial or clerical position.[30]

The WAVES enjoyed many successes in the workplace, but they also suffered from a degree of intolerance. Some of the problems sprang from contradictory attitudes of the men who supervised the women. Often, the women were underutilized in relation to their training, with others it was assignments beyond their physical abilities, and in some cases the women were utilized only out of dire need. The mission of the WAVES was to replace the men in shore stations for sea duty. Some of the men were hostile to the WAVES, because being replaced meant sea duty. The Navy's lack of clear-cut policies early on also contributed to the difficulties.[45]

Personnel

_are_the_first_Neg_-_NARA_-_520634.jpg)

Wanting to serve her country in the time of need was a strong incentive for a young woman during World War II; thousands of them saw fit to join the WAVES. With some, it was the lure of adventure, for others it was the professional development, and still others joined for the chance to experience life on college campuses. Some followed family traditions and others yearned for a life other than as a civilian.[46]

Ruby Messer Barber had this to say about joining the WAVES, "It was a choice of adventure. I didn't have any brothers, and I thought that's something I can do, one way I can make a contribution. My sisters thought it was great, but they were not interested. There was too much discipline and routine involved. I felt like it would be a challenge, to step forth and do it, to see what it was all about. It gave a sense of confidence. At the time girls just didn't join the WAVES or go into the military. But my Dad, he said, you'll be OK".[47]

Lieutenant Lillian Pimlott wrote to her mother, after being deployed to Pearl Harbor, and said, "I was fascinated by the ships which are making history in every battle. I've talked to seamen and I've met flyers-from Iwo (Iwo Jima), from Okinawa, heroes from every encounter. I know now what war means and my heart goes out to every one of them. Among them I am making, I hope, life long friends, for their experiences mean everything to my self-satisfaction ... As long as they fight on, I have no desire to return home, for I feel I belong here ... I have learned much in these brief three months about life and living. And I know I have already changed in many ways and many viewpoints ... It is truly a most broadening experience and I shall never outlive it".[48]

During the course of the war, seven WAVE officers and 62 enlisted women died of unspecified causes. Many of the WAVES were acknowledged for their contributions to the country. The Distinguished Service Medal was awarded to Captain Mildred McAfee for her efforts as Director of the WAVES, and Commander Elizabeth Reynard received a letter of commendation from the Secretary of the Navy for her work in developing the WAVES training program. Two of the WAVES received the Legion of Merit, three the Bronze Star, eighteen the Secretary of the Navy's letter of commendation, and one, the Army Commendation Ribbon. Almost all of the WAVES looked upon their service as beneficial and many said they would serve again under the same situation.[49]

Demobilization

At the end of the war, the Navy established five separation centers for the demobilization of the WAVES and for the Navy nurses. These were located in Washington, D.C., Memphis, San Francisco, Chicago, and New York. The separation process began on 1 October 1945, and within a month about 9,000 of the WAVES had been separated. By the end of 1946, almost 21,000 more had been discharged. It soon became apparent that more centers were needed and ten additional centers were soon opened. By September 1946, the demobilization of the WAVES was all but completed. Most women spent two or three days at the separation centers before being discharged, having physical exams; orientation on rights as veterans; final settlement of pay, and then the price of a ticket home.[50] At the time, it was not clear whether the demobilization meant phasing the women out of the military services altogether.[51]

Although a small contingent of WAVES was retained to help with the Navy's over-all demobilization plan, many of these women had volunteered to remain on active duty. At that point, Vice Admiral Louis Denfeld, chief of the Bureau of Personnel, announced, "Our plan is to keep a WAVE component in the Naval Reserve. Further, if Congress approves, we will seek to retain on active duty a reasonable number of WAVES who wish to do so and who may be needed in certain specialties ..."[52] On 30 July 1948, the Women's Armed Services Integration Act (Public Law 625) was signed into law, allowing the women to serve in the regular Navy.[53] The wartime assumptions that prohibited the women from duty in any unit designated as having a combat mission carried over with the 1948 Act, which effectively incorporated the women into the service organizations, legally keeping them from being integrated into the heart of the military and naval professions for more than a quarter of a century. Even though the WAVES no longer existed, the obsolete acronym continued in popular and official usage until the 1970s.[54]

With the demobilization, the WAVES received accolades from the highest sources. Secretary of the Navy Forrestal wrote, "Your conduct, discharge of military responsibilities, and skillful work are in the highest tradition of the naval service." Fleet Admiral King said, "The Navy has learned to appreciate the women ... for their discipline, their skill, and their contribution to high morale ... Our greatest tribute to these women is the request for more WAVES". Fleet Admiral Nimitz went on to say, "they have demonstrated qualities of competence, energy and loyalty".[55] The WAVES left behind a legacy of accomplishment, which helped to secure a place for the women in the regular Navy.[56]

Song of the WAVES

Elizabeth Ender and Betty St. Clair wrote WAVES of the Navy in 1943. It was written to harmonize with Anchors Aweigh.[57]

- WAVES of the Navy

- WAVES of the Navy,

- There's a ship sailing down the bay

- And she won't slip into port again

- Until that Victory Day.

- Carry on for that gallant ship

- And for every hero brave

- Who will find ashore, his man-sized chore

- Was done by a Navy WAVE.[57]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Ebert and Hall p. 27

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 27–28

- ↑ Hancock p. 50

- ↑ Hancock pp. 50–52

- ↑ Hancock p. 53

- 1 2 Goodson p. 110

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 30–31

- 1 2 Ebert and Hall p. 31

- ↑ Walsh cited in Goodson p. 110

- 1 2 Ebert and Hall p. 32

- ↑ Ebert and Hall p. 34

- 1 2 Goodson p. 111

- 1 2 3 Goodson p. 113

- ↑ Hancock p. 61

- 1 2 Ebert and Hall p. 35

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 36–37

- ↑ Hancock p. 70

- ↑ Collins p. 43

- ↑ Collins p. 42

- ↑ Hancock p. 65

- ↑ Goodson pp. 113–114

- ↑ Goodson p. 115

- ↑ Goodson p. 116

- ↑ MacGregor pp. 74–75

- 1 2 MacGregor pp. 86–88

- ↑ MacGregor p. 247

- ↑ Goodson p. 124

- ↑ Hancock p. 152

- ↑ Ebert and Hall p. 43

- 1 2 3 Goodson p. 125

- ↑ Hancock pp. 75–76

- ↑ Ebert and Hall p. 48

- ↑ Goodson p. 117

- ↑ Hancock p. 77

- ↑ Hancock p. 78

- ↑ Goodson pp. 118–119

- ↑ Goodson p. 119

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 61–63

- ↑ Hancock p. 102

- 1 2 3 Goodson p. 120

- ↑ Hancock p. 104

- ↑ Goodson p. 127

- ↑ Goodson p. 128

- ↑ Goodson p. 126

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 74–77

- ↑ Goodson pp. 116–117

- ↑ Yellin p. 139

- ↑ Yellin p. 141

- ↑ Goodson pp. 128–129

- ↑ Ebert and Hall pp. 92–93

- ↑ Collins p. 91

- ↑ Hancock p. 216

- ↑ Hancock p. 232

- ↑ Ebert and Hall p. 113

- ↑ Goodson p. 129

- ↑ Ebert and Hall p. 95

- 1 2 Ebert and Hall p. 74

Bibliography

- Collins, Winifred Quick Captain, U.S. Navy (Retired) (1997). More Than A Uniform. with Levine, Herbert M. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 1-57441-022-9.

- Ebert, Jean; Hall, Marie-Beth (1993). Crossed Currents. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-193-6.

- Goodson, Susan, H. (2001). Serving Proudly. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-317-6.

- Hancock, Joy Bright Captain, U.S. Navy (Retired) (1972). Lady in the Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-336-9.

- MacGregor, Morris J., Jr. (2001). Integration of the Armed Forces 1940-1965 (PDF). Defense Studies Series. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 713016456. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Yellin, Emily (2004). Our Mothers' War. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-4514-8.

Further reading

- Campbell, D'Ann (1984). Women at War With America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-95475-5. OCLC 10605327.

- Campbell, D'Ann (July 1987). "Women in Uniform: The World War II Experiment". Military Affairs (51): 137–139. ISSN 0026-3931.

- Gildersleeve, Virginia, C. (1954). Many a Good Crusade. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 1005942723.

- Holm, Jeanne; Bellafare, Judith (1998). In Defense of a Nation: Servicewomen in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Military Women's Press. ISBN 978-0-91833-943-0.

- Holm, Jeanne Major General, USAF (Retired) (1972). Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution (Revised ed.). Novato, CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-450-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. |

- Campbell, D'Ann (Winter 1990). "Servicewomen of World War II". Armed Forces and Society. 16 (2): 251–270. ISSN 1556-0848.

- "Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Collection". University of North Carolina Greensboro. 1998. – digitized letters, diaries, photographs, uniforms, and oral histories from WAVES and other female service orgs

- blitzkriegbaby (2006). Women's Reserve of the US Naval Reserve (WAVES).

- blitzkriegbaby (2006). "Sources". Women's Reserve of the US Naval Reserve (WAVES). – annotated bibliography of books and films

- The Bureau of Naval Personnel (1943). "Summary of Ranks and Rates of the U.S. Navy Together With Designations and Insignia [NAVPERS-15004]". Information Bulletin (Hyperwar reprint ed.) (May).

- Chen, C. Peter (2018). "WAVES: Women in the WW2 US Navy". World War II Database. Lava Development, LLC.

- "Oral history interview with Constance Sullivan Cain, a member of the WAVES from 1944–1946". Veterans History Project. Center for Public Policy and Social Research, Central Connecticut State University. 2008.

- Waves. Special Collections, Georgia College and State University Library. — Photographs of WAVES being trained at the Georgia State College for Women from 1943 to 1945