Villain

A villain (also known as, "baddie", "bad guy", "evil guy", "heavy" or "black hat") is an "evil" character in a story, whether a historical narrative or, especially, a work of fiction.

The villain usually is the antagonist (though can be the protagonist), the character who tends to have a negative effect on other characters. A female villain is occasionally called a villainess. Random House Unabridged Dictionary defines villain as "a cruelly malicious person who is involved in or devoted to wickedness or crime; scoundrel; or a character in a play, novel, or the like, who constitutes an important evil agency in the plot".[1]

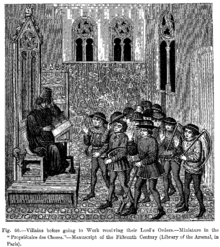

Etymology

Villain comes from the Anglo-French and Old French vilain, which itself descends from the Late Latin word villanus, meaning "farmhand",[2] in the sense of someone who is bound to the soil of a villa, which is to say, worked on the equivalent of a plantation in Late Antiquity, in Italy or Gaul.[3] The same etymology produced villein.[4] It referred to a person of less than knightly status and so came to mean a person who was not chivalrous and polite. As a result of many unchivalrous and evil acts, such as treachery or rape, being considered villainous in the modern sense of the word, it became used as a term of abuse and eventually took on its modern meaning.[5] The Germanic word "churl", originally meaning "a non-servile peasant" and denoting the lowest rank of freemen in Saxon society, had gone through a similar degradation, as did the word "boor" which originally meant "farmer".

Folk and fairy tales

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight dramatis personae, of which one was the villain,[6]:79 and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian tales. The actions that fell into a villain's sphere were:

- a story-initiating villainy, where the villain caused harm to the hero or his family

- a conflict between the hero and the villain, either a fight or other competition

- pursuing the hero after he has succeeded in winning the fight or obtaining something from the villain

None of these acts necessarily occurs in a fairy tale, but when any of them do, the character that performs the act is the villain. The villain, therefore, could appear twice: once in the opening of the story, and a second time as the person sought out by the hero.[6]:84

When a character performed only these acts, the character was a pure villain. Various villains also perform other functions in a fairy tale; a witch who fought the hero and ran away, and who lets the hero follow her, is also performing the task of "guidance" and thus acting as a helper.[6]:81

The functions could also be spread out among several characters. If a dragon acted as the villain but was killed by the hero, another character (such as the dragon's sisters) might take on the role of the villain and pursue the hero.[6]:81

Two other characters could appear in roles that are villainous in the more general sense. One is the false hero: this character is always villainous, presenting a false claim to be the hero that must be rebutted for the happy ending.[6]:60 Among these characters are Cinderella's stepsisters, chopping off parts of their feet to fit on the shoe.[7] Another character, the dispatcher, sends a hero on his quest. This might be an innocent request, to fulfill a legitimate need, but the dispatcher might also, villainously, lie to send a character on a quest in hopes of being rid of him.[6]:77

Villainous foil

In fiction, villains commonly function in the dual role of adversary and foil to the story's heroes. In their role as an adversary, the villain serves as an obstacle the hero must struggle to overcome. In their role as a foil, the villain exemplifies characteristics that are diametrically opposed to those of the hero, creating a contrast distinguishing heroic traits from villainous ones.

Others point out that many acts of villains have a hint of wish-fulfillment,[8] which makes some people identify with them as characters more strongly than with the heroes. Because of this, a convincing villain must be given a characterization that provides a motive for doing wrong, as well as being a worthy adversary to the hero. As put by film critic Roger Ebert:

"Each film is only as good as its villain. Since the heroes and the gimmicks tend to repeat from film to film, only a great villain can transform a good try into a triumph."[9]

Portraying and employing villains in fiction

Tod Slaughter always portrayed villainous characters on both stage and screen in a melodramatic manner, with mustache-twirling, eye-rolling, leering, cackling, and hand-rubbing (however, this often failed to translate well from stage to screen).[10][11] Brad Warner states that "only cartoon villains cackle with glee while rubbing their hands together and dream of ruling the world in the name of all that is wicked and bad".[12] Ben Bova recommends to authors that their works not contain villains. He states, in his Tips for writers:

"In the real world there are no villains. No one actually sets out to do evil... Fiction mirrors life. Or, more accurately, fiction serves as a lens to focus on what they know in life and bring its realities into sharper, clearer understanding for us. There are no villains cackling and rubbing their hands in glee as they contemplate their evil deeds. There are only people with problems, struggling to solve them."[13]

David Lubar adds:

"This is a brilliant observation that has served me well in all my writing. (The bad guy isn't doing bad stuff so he can rub his hands together and snarl.) He may be driven by greed, neuroses, or the conviction that his cause is just, but he's driven by something, not unlike the things that drive a hero."[14]

Sympathetic villain

In an attempt to add realism to their stories, many writers will try to create "sympathetic" villains, the antithesis to an antihero called an anti-villain. These villains come in just as many shapes and sizes as anti-heroes do. Some may wish to make the world a better place but go to antagonistic lengths to do so (such as Doctor Octopus in Spider-Man 2, who commits various crimes in an attempt to complete his goal of creating a cheap, renewable source of energy, and Dr. Horrible in Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog, who wants to rule the world so that he can solve all of its problems), or may employ a code of honor in fighting his enemies, even if it is to achieve antagonistic goals (examples include Murdock, a secondary villain in the game Fire Emblem: Fūin no Tsurugi, who is honorable, but fights the player's army due to loyalty to his country). Other sympathetic villains may be pushed to antagonistic lifestyles by society's mistreatment of him due to prejudice against something he is a part of (such as racism, as is the case in American History X), but goes to absurd lengths to achieve the equality he desires, like Magneto in the X-Men comics and films. Others may include those manipulated by malevolent and opprobrious forces (such as Jack Torrance being manipulated by the Overlook Hotel in The Shining).

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Villain |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Motivation and emotion/Book/2016/Villain motivations |

- Antagonist

- Antihero

- Antithesis

- Adversary

- Archnemesis

- Archenemy

- Archrival

- Boss (crime)

- Criminal

- Enemy

- Evil

- Evil laughter

- Filmfare Award for Best Performance in a Negative Role. Since 1991, Bollywood recognizes the best actors portraying a villain.

- Foil (literature)

- Heel (professional wrestling)

- List of soap opera villains

- Mad scientist

- Nemesis (mythology)

- Rival (disambiguation)

- Supervillain

- Tragic Hero

- Tyrant

References

- ↑ "villain". Dictionary.com. Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 2014-04-02. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Robert K. Barnhart; Sol Steinmetz (1999). Chambers Dictionary of Etymology. New York: Chambers. p. 1204. ISBN 0550142304.

- ↑ David B. Guralnik (1984). Webster's New World Dictionary (2nd college ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671418149.

- ↑ "villain". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ C. S. Lewis (2013). Studies in Words. Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9781107688650. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vladimir Propp (1968). Morphology of the Folk Tale (2nd ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292783760.

- ↑ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 136 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ↑ Das, Sisir Kumar (1995). A History of Indian Literature: 1911-1956. Sahitya Akademi. p. 416. ISBN 9788172017989. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (January 1, 1982). "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan Movie Review (1982)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Bryan Senn (1996). Golden Horrors: An Illustrated Critical Filmography of Terror Cinema, 1931-1939. McFarland. p. 481. ISBN 9780786401758.

- ↑ Jeffery Richards (2001). The Unknown 1930s: An Alternative History of the British Cinema, 1929-39. I.B. Tauris. p. 150. ISBN 9781860646287.

- ↑ Brad Warner (2007). Sit Down and Shut Up: Punk Rock Commentaries on Buddha, God, Truth, Sex, Death, and Dogen's Treasury of the Right Dharma Eye. New World Library. p. 119. ISBN 9781577315599.

- ↑ Ben Bova (2008-01-28). "Tips for writers". Ben Bova. Archived from the original on 2009-08-21. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ↑ "Villains Don't Always Wear Black". Revision Notes. Darcy Pattison. 2008-01-28. Archived from the original on 2009-01-22.