Vienna Convention on Consular Relations

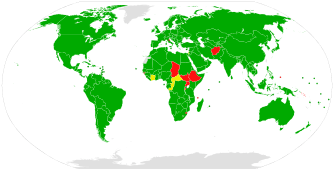

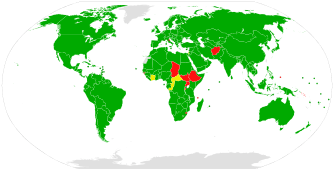

Parties to the convention

Parties Signatories Non-signatories | |

| Drafted | 22 April 1963 |

|---|---|

| Signed | 24 April 1963 |

| Location | Vienna |

| Effective | 19 March 1967 |

| Condition | Ratification by 22 states |

| Signatories | 48 |

| Parties | 179 (as of May 2016)[1] |

| Depositary |

UN Secretary-General (Convention and the two Protocols)[2] Federal Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Austria (Final Act)[2] |

| Citations | 500 U.N.T.S. 95; 23 U.S.T. 3227 |

| Languages | Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish[2] |

|

| |

The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 1963 is an international treaty that defines a framework for consular relations between independent states. A consul normally operates out of an embassy in another country, and performs two functions: (1) protecting in the host country the interests of their countrymen, and (2) furthering the commercial and economic relations between the two states.

The treaty provides for consular immunity.[3] The treaty has been ratified by 179 states.[1]

History

The Convention was adopted at Vienna on April 24, 1963, the United Nations Conference on Consular Relations, which took place at the Neue Hofburg from March 4 to April 22, 1963. Its official texts are in the English, French, Chinese, Russian and Spanish languages, which the Convention provides are equally authentic.[2]

Key provisions

The treaty contains 79 articles.[2] The preamble to the Convention states that customary international law continues to apply to matters not addressed in the Convention.[2][3] Some significant provisions include.[2]

- Article 5 lists thirteen functions of a consul, including "protecting in the receiving State the interests of the sending State and of its nationals, both individuals and bodies corporate, within the limits permitted by international law" and "furthering the development of commercial, economic, cultural and scientific relations between the sending State and the receiving State."[2]

- Article 23 provides that the host nation may at any time and for any reason declare a particular member of the consular staff to be persona non grata, and the sending state must recall this person within a reasonable period of time, or otherwise this person may lose their consular immunity.[2]

- Article 31 provides that the consular premises are inviolabile (i.e., the host nation may not enter the consular premises, and must protect the premises from intrusion or damage).[2]

- Article 35 provides that freedom of communication between the consul and their home country must be preserved, that consular bags "shall be neither opened nor detained"; and that a consular courier must never be detained.[2]

- Article 37 provides that with the host country must "without delay" notify consular officers of the sending state if one of the sending state's nationals dies or has a guardian or trustee appointed over him. The article also provides that consular officers must be informed "without delay" if a vessel with the sending state's nationality is wrecked or runs aground "in the territorial sea or internal waters of the receiving State, or if an aircraft registered in the sending State suffers an accident on the territory of the receiving State."[2]

- Article 36 addresses communications between consular officers and nationals of the sending state. The Convention provides that "consular officers shall be free to communicate with nationals of the sending State and to have access to them." Foreign nationals who are arrested or detained be given notice "without delay" of their right to have their embassy or consulate notified of that arrest, and "consular officers shall have the right to visit a national of the sending State who is in prison, custody or detention, to converse and correspond with him and to arrange for his legal representation."[2]

- Article 40 provides that "The receiving State shall treat consular officers with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on their person, freedom or dignity."[2]

- Articles 58-68 deal with honorary consular officers and their powers and functions.[2]

Consular immunity

The Convention (Article 43)[2] provides for consular immunity. Some but not all provisions in the Convention regarding this immunity reflect customary international law.[3] Consular immunity is a lesser form of diplomatic immunity. Consular officers and consular employees have "functional immunity" (i.e., immunity from the jurisdiction of the receiving state "in respect of acts performed in exercise of consular function"), but do not enjoy the broader "personal immunity" accorded to diplomats.[3]

State parties to the convention

There are 179 state parties to the convention including most UN member states and UN observer states Holy See and State of Palestine. The signatory states that have not ratified the convention are: Central African Republic, Israel, Ivory Coast and Republic of Congo. The UN member states that have neither signed nor ratified the convention are: Afghanistan, Burundi, Chad, Comoros, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Palau, San Marino, Solomon Islands, South Sudan, Swaziland and Uganda.

Application of the treaty by the United States

In March 2005, following the decisions of the International Court of Justice in the LaGrand case (2001) and Avena case (2004), the United States withdrew from the Optional Protocol to the Convention concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes, which confers the ICJ with compulsory jurisdiction over disputes arising under the Convention.[4][5]

In 2006, the United States Supreme Court ruled that foreign nationals who were not notified of their right to consular notification and access after an arrest may not use the treaty violation to suppress evidence obtained in police interrogation or belatedly raise legal challenges after trial (Sanchez-Llamas v. Oregon).[6] In 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court further ruled that the decision of the ICJ directing the United States to give "review and reconsideration" to the cases of 51 Mexican convicts on death row was not a binding domestic law and therefore could not be used to overcome state procedural default rules that barred further post-conviction challenges (Medellín v. Texas).[7]

In 1980, prior to its withdrawal from the Optional Protocol, the U.S. brought a case to the ICJ against Iran—United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (United States v Iran)—in response to the seizure of United States diplomatic offices and personnel by militant revolutionaries.[8]

References

- 1 2 "Vienna Convention on Consular Relations". United Nations Treaty Collection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Vienna Convention on Consular Relations" (PDF). United Nations Treaty Series.

- 1 2 3 4 Boleslaw Adam Boczek, International Law: A Dictionary (Scarecrow Press, 2014), pp. 41-42.

- ↑ Jan Wouters, Sanderijn Duquet & Katrien Meuwissen, "The Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relations" in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (eds. Andrew F. Cooper, Jorge Heine & Ramesh Thakur: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 515-16.

- ↑ Andreas Zimmermann, "Between the Quest for Universality and its Limited Jurisdiction: The Role of the International Court of Justice in enhancing the International Rule of Law" in Enhancing the Rule of Law through the International Court of Justice (eds. Giorgio Gaja & Jenny Grote Stoutenburg: Brill Nijhoff, 2014), p. 40.

- ↑ Sanchez-Llamas v. Oregon, 548 U.S. 331 (2006).

- ↑ Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491 (2008).

- ↑ International Court of Justice, 24 May 1980, Case Concerning United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran Archived 13 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- Text of the Convention

- Implications of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations upon the Regulation of Consular Identification Cards

- U.S. Quits Pact Used in Capital Cases: Foes of Death Penalty Cite Access to Envoys – Washington Post article by Charles Lane

- Introductory note by Juan Manuel Gómez Robledo, procedural history note and audiovisual material on the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- Lecture by Eileen Denza entitled Diplomatic and Consular Law – Topical Issues in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law