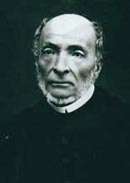

Victor Schœlcher

Victor Schœlcher (French pronunciation: [ʃœl.ʃεʁ]; 22 July 1804 – 25 December 1893) was a French abolitionist writer in the 19th century and the main spokesman for a group from Paris who worked for the abolition of slavery, and formed an abolition society in 1834. He worked especially hard for the abolition of slavery on the Caribbean islands, notably the French West Indies.

Biography

Schœlcher was born in Paris on 22 July 1804. His father, Marc Schœlcher (1766–1832), from Fessenheim in Alsace, was the owner of a porcelain factory.[1] His mother, Victoire Jacob (1767–1839), from Meaux in Seine-et-Marne, was a laundry maid in Paris at the time of their marriage. Victor Schœlcher was baptized in Saint-Laurent Church on 9 September 1804.

He studied at the Lycée Condorcet, became a journalist, opposing the government of Louis Philippe and making a reputation as a pamphleteer. After 1826 he devoted himself almost exclusively to advocacy of the abolition of slavery throughout the world, contributing a part of his large fortune to establish and promote societies for the benefit of blacks.

He was sent to visit America for business from 1829 to 1830. While in America he visited Mexico, Cuba and some of the southern states of the U.S. On this trip Schœlcher learned a lot about slavery and began his career as an abolitionist writer. From 1840 to 1842 he visited the West Indies, and from 1845 to 1847 Greece, Egypt, Turkey, and the west coast of Africa to study slavery.

He was responsible for the publication of many articles regarding slavery between 1833 and 1847 in which he focused on positive aspects of abolishing slavery. Schœlcher was also intent on social, economic, and political changes being made in the Caribbean colonies. He thought that the production of sugar should continue in the colonies but large central factories should be constructed rather than using slave labor. Schœlcher was the first European abolitionist to visit Haiti and had a large influence on the abolitionist movements in all of the French West Indies. He was actively against the debt collected from the Haitians as French slave owners sought reparations for their lost property after the Haitian Revolution.[2]

On 3 March 1848, he was appointed under-secretary of the navy, and caused a decree to be issued by the provisional government which acknowledged the principle of the enfranchisement of the slaves through the French possessions. As president of a commission, Schœlcher prepared and wrote the decree of 27 April 1848 in which the French government announced that slavery was abolished in all of its colonies.

He was elected to the legislative assembly in 1848 and 1849 for Martinique, and introduced a bill for the abolition of the death penalty, which was to be discussed on the day on which Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte made his coup d'état. Disagreeing with this action, on 2 December 1851 he went into exile in Belgium and then London.

Refusing to take advantage of the amnesties of 1856 and 1869, he returned to France only after the declaration of war with Prussia in 1870. Organizing a legion of artillery, he took part in the defence of Paris. In 1871 he was elected again to the national assembly for Martinique. Schœlcher was the most well informed French public figure on the Caribbean colonies and after 1871 developed a group of correspondents between the Caribbean, Great Britain and the United States. He was elected senator for life in 1875.

Schœlcher published his last writings in 1889. After fighting for and writing for the abolition of slavery and French colonialism in the Caribbean for a large portion of the 19th century, Schœlcher died in 1893. First buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Schœlcher's remains were transferred on 20 May 1949 to the Panthéon. Félix Éboué's ashes were also transferred at the same time. In 1981, the newly elected President Francois Mitterrand placed a rose at his tomb in the Pantheon as part of his inauguration ceremony.

Works

- De l'esclavage des noirs et de la législation coloniale (On slavery of blacks and colonial legislation) (Paris, 1833)

- Abolition de l'esclavage (Abolition of slavery) (1840)

- Les colonies françaises de l'Amérique (French colonies of America) (1842)

- Les colonies étrangères dans l'Amérique et Hayti (Foreign colonies in America and Haiti) (2 vols., 1843)

- Histoire de l'esclavage pendant les deux dernières années (History of slavery during the last two years) (2 vols., 1847)

- La verité aux ouvriers et cultivateurs de la Martinique (The truth to the workers and farmers of Martinique) (1850)

- Protestation des citoyens français negres et mulatres contre des accusations calomnieuses (Protests of black and mulatto French citizens against slanderous accusations) (1851)

- Le procès de la colonie de Marie-Galante (The trial of the Marie-Galante colony) (1851)

- La grande conspiration du pillage et du meurtre à la Martinique (The big conspiracy of theft and murder in the Martinique) (1875)

- The Life of Handel, translated by James Lowe

Legacy

- In homage to his fight against slavery, the commune of Case-Navire (Martinique) took the name of Schœlcher in 1888.

- The commune of Fessenheim made from his family's house the Victor Schœlcher museum.

- The Place Victor Schœlcher in Aix-en-Provence is named for him.[3]

- A street created at the south-eastern corner of the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris was named Rue Schœlcher in 1894 and Rue Victor Schœlcher in 2000.

- Two ships of the French Navy have been named Victor Schœlcher - an auxiliary cruiser during World War II, and a Commandant Rivière-class frigate in service 1962-1988.

Notes

- ↑ "Victor Schoelcher (1804-1893) Une vie, un siècle". senat.fr. Senate (France). Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Jublin, Matthieu, ed. (12 May 2015). "French President's Debt Comment in Haiti Reopens Old Wounds About Slave Trade". Vice News. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Aix Google Map

References

- Jan Rogozinski – A Brief History Of The Caribbean (New York: Plume, 2000)

- James Chastain – Victor Schœlcher. Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions 2004 James Chastain .

External links

- Schœlcher, Victor. De la pétition des ouvriers pour l'abolition immédiate de l'esclavage, Paris, Pagnerre, 1844. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Restauration de la traite des noirs à Natal, Paris, Imprimerie E. Brière, 1877. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Evénements des 18 et 19 juillet 1881 à Saint-Pierre (Martinique), Paris, Dentu, 1882. Manioc

- Schœlcher, Victor. Conférence sur Toussaint Louverture, général en chef de l'armée de Saint-Domingue, [s.l.], Editions Panorama, 1966. Manioc

- Monnerot, Jules. Schœlcher, [s.l.], Imprimerie Marchand, 1936. Manioc

- Basquel, Victor. Un grand ancêtre : Victor Schœlcher (1804-1893), Rodez, Imprimerie P. Carrère, 1936. Manioc

- Magallon Graineau, Louis-Alphonse Eugène. L'exemple de Victor Schœlcher, Fort-de-France, Imprimerie officielle, 1944. Manioc