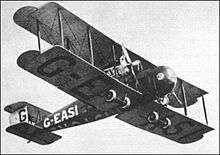

Vickers Vimy

| Vimy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Heavy bomber |

| Manufacturer | Vickers Limited |

| Designer | Reginald Kirshaw Pierson |

| First flight | 30 November 1917 |

| Introduction | 1919 |

| Retired | 1933 |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Variants | Vickers Vernon |

The Vickers Vimy was a British heavy bomber aircraft developed and manufactured by Vickers Limited. Developed during the latter stages of the First World War to equip the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), the Vimy was designed by Reginald Kirshaw "Rex" Pierson, Vickers' chief designer.

Only a handful of aircraft had entered service by the time the Armistice of 11 November 1918 came into effect, thus the type was not used in active combat operations during the conflict. Shortly thereafter, the Vimy became the core of the RAF's heavy bomber force throughout the 1920s. The Vimy achieved success as both a military and civil aircraft, the latter using the Vimy Commercial model of the type. A dedicated transport derivative of the Vimy, the Vickers Vernon, became the first dedicated troop transport aircraft to be operated by the RAF.

During the interwar period, the Vimy set several notable records for long-distance flights; perhaps the most celebrated and significant of these was the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, which was performed by John Alcock and Arthur Brown in June 1919. Other record-breaking flights were flown using the type from the United Kingdom to destinations such as South Africa and Australia. The Vimy continued to be operated after the conflict as late as the 1930s in both military and civil capacities.

Development

Origins

Throughout the First World War, both the Allied Powers and the Central Powers made increasingly sophisticated use of new technologies in their attempts to break through the effective stalemate of trench warfare. One key advance made during the conflict was in the use of fixed-wing aircraft, which were at that time rapidly advancing in capability and ability, for combat purposes.[1] On 23 July 1917, in response to a bombing raid performed by German bomber aircraft upon the city of London, the Air Board, having determined that existing projects were not ambitious enough, decided to cancel all orders for experimental heavy bombers then underway. One week later, following the heavy protests of the Controller of the Technical Department, the Air Board placed an order for 100 Handley Page O/100 bombers, which was accompanied by orders for prototype heavy bombers being placed with both Handley Page and Vickers Limited.[1]

On 16 August 1917, Vickers was issued with a contract for an initial batch of three prototype aircraft.[1] Accordingly, Reginald Kirshaw "Rex" Pierson, chief designer of Vickers Limited (Aviation Department) in Leighton Buzzard, set about designing a large twin-engine biplane bomber, which could be powered by either a pair of RAF 4d or 200 hp (150 kW) Hispano Suiza engines.[1] Pierson discussed the proposed aircraft with Major J.C. Buchanan of the Air Board for the purpose of establishing the rough configuration of the aircraft, which was expected to conform with a requirement for a night bomber that would be capable of attacking targets within the German Empire.[2][1] Design and production of the prototypes was extremely rapid; the detailed design phase of what had become internally designated as the Vickers F.B.27, along with the manufacture of the three prototypes, was completed within four months.[1]

Prototypes

By the time the first prototype had been completed, the RAF 4D had yet to be sufficiently developed to be installed on the aircraft, so it was outfitted with the alternative Hispano Suiza engine instead.[1] On 30 November 1917, the first prototype, flown by Captain Gordon Bell, conducted its maiden flight from Royal Flying Corps Station Joyce Green, Kent.[3] In January 1918, the first prototype was dispatched to RAF Martlesham Heath, Suffolk, to participate in official trials of the type. Reportedly, the F.B.27 quickly made a positive impression when it was able to take off while carrying a greater payload that the Handley Page O/400 while possessing almost half the effective engine power.[1] Unfortunately, the engines proved to be frequently unreliable during these trials, leading to its return to Joyce Green on 12 April 1918.[1]

The first prototype was thus extensively modified, receiving new Salmson water-cooled aero-engines instead of the Hispano Suiza engines, along with other changes, such as the adoption of an alternative exhaust stack configuration, a 3-degree dihedral on the mainplanes, and a tail unit more representative of production aircraft.[1] Following these modifications, the prototype was used for several years, surviving the war and being allocated a civil registration. In August 1919, the prototype was flown from Brooklands to Amsterdam, the Netherlands as part of Vicker's exhibit at the Eerste Luchtverkeer Tentoonstelling Amsterdam.[1]

During early 1918, the second prototype was completed.[4] Unlike the first prototype, it had plain elevators and ailerons that had an inverse taper; the tops of the wings and tailplanes also differed. The defensive armament was increased, giving the rear gunner two separate guns to fire; these changes would be standardised on production aircraft.[4] The second prototype was powered by a pair of Sunbeam Maori engine, which were found to have an unreliable cooling system during initial testing at Joyce Green. On 26 April 1918, the aircraft was dispatched to RAF Matlesham Heath for official tests; however, testing was interrupted by the loss of the second prototype in a crash following an engine failure.[4]

During the first half of the 1918, the third prototype was also completed.[4] It was equipped with a pair of 400 hp (300 kW) Fiat A.12 engines, as well as a redesigned nose section and nacelles that were similar to production aircraft. On 15 August 1918, the third prototype was sent to RAF Martlesham Heath for performance tests; testing was delayed by the need to replace a cracked propeller.[4] On 11 September 1918, this prototype was lost when its payload of bombs detonated owing to a hard landing, which in turn had been the result of a pilot-induced stall.[4]

It was decided to construct a fourth prototype to test the Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engine.[5] On 11 October 1918, the fourth prototype flew from Joyce Green to Martlesham to conduct official trials. Aside from being powered by the Eagle engine, it was otherwise identical to earlier prototypes except for a greatly increased fuel capacity and reshaped and enlarged rudders.[6] By the time the fourth prototype commenced flying trials, mass production of the Vimy had already commenced.[7]

Production

Satisfied with the demonstrated performance of the first prototype, it was decided to proceed to production prior to the evaluation of either of the other prototypes.[4] On 26 March 1918, the first production contract for 150 aircraft was issued; work on this batch was performed at Vickers' facility in Crayford in the London Borough of Bexley. Production of the type by additional manufacturers was envisaged early on; in May 1918, follow-up contracts were issued to Clayton & Shuttleworth, Morgan & Co, and the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), in addition to a separate production line at Vickers' Weybridge complex.[8] At one point, over 1,000 aircraft had been ordered under wartime contracts, which had received the official name of Vimy, after the Battle of Vimy Ridge.[9]

By the end of 1918, a total of 13 aircraft had been completed by Vickers; 7 at Crayford and 6 at Weybridge.[7] Vimy production continued after the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918, which led to Vickers ultimately completing 112 aircraft under wartime contracts. The majority, if not all, of Vimys ordered from Morgan & Co were completed, while Westland Aircraft manufactured 25 of the 75 units that they were contracted for.[7] The numbers produced by the RAE are obscured by changes in serial number nomenclature and the apparent adoption of a piecemeal approach to manufacturing, which came into effect shortly after the end of the conflict; in February 1920, the RAE completed their final Vimy.[10]

Production aircraft used several different types of engines, leading to various mark numbers being applied to the Vimy to distinguish between the emerging subtypes.[9] The use of different engines was often because of availability; relatively few engines from Rolls-Royce Limited were used in the Vimy during 1918 owing to low output levels from that manufacturer, while other manufacturers also struggled to keep up with engine demand during that same year. At one point, there was considerable enthusiasm for powering the Vimy with American Liberty L-12 engines instead because of their plentiful supply at the time; while specified for production aircraft, though, all orders for the Liberty-equipped Vimy were terminated in January 1919 and no examples were ever completed.[9] The BHP Puma was another engine that had been intended for use on the Vimy, but the Puma was cancelled without any aircraft being fitted with the engine.[9]

Use of the Vimy extended beyond its original use as a bomber. A dedicated model with greater internal space was developed, known as the Vimy Commercial within the civil market.[11] The Vimy Commercial would see service with the RAF; known as the Vickers Vernon, it became the first dedicated troop transport to be operated by the service. The Vimy was also used as an air ambulance for transporting wounded troops to medical facilities, while some examples were configured to perform record-breaking long distance flights.[11] From 1923 to 1925 limited production batches of the Vimy were manufactured by Vickers. Additionally, between 1923 and 1931, a minimum of 43 early production aircraft were reconditioned in order to extend their viable service lives; at least one Vimy was reconditioned four times.[12]

Design

The Vickers F.B.27 Vimy was a heavy bomber aircraft, designed to accommodate a three-man crew alongside a payload of 12 bombs.[1] In addition to the pilot's cockpit, which was positioned just ahead of the wings, there were two separate cockpits for gunners, who were each provided with Scarff ring-mounted Lewis guns, located behind the wings and in the nose of the aircraft.[1] The total defensive armament consisted of four .303 Mk.III Lewis guns divided between the two positions, although the rear cockpit mounting was commonly not fitted during the interwar period. Provisions for a maximum of four spare drums of ammunition were present in the nose cockpit, while up to six drums could be contained within the rear.[13]

The majority of Vimy's main armament of 250 lb bombs were stowed vertically within the fuselage, between the spars of the lower-center section; a typical payload consisted of 12 bombs.[1] In some variants further bombs could be stowed across several external positions for a total of 18 bombs, depending on the particular engine used to provide enough power.[14] For anti-surface warfare in the maritime environment, the Vimy could also be armed with a pair of torpedoes. To improve bombing accuracy, the Vimy was equipped with the High Altitude Drift Mk.1a bombsight. Standard equipment also included two Michelin-built Mk.1 flare carriers.[13]

The Vimy was powered by a range of different engines. Owing to engine supply difficulties, the prototype Vimys were tested with a number of different engine types, including Sunbeam Maoris, Salmson 9Zm water-cooled radials, and Fiat A.12bis engines, before production orders were placed for aircraft powered by the 230 hp (170 kW) BHP Puma, 400 hp (300 kW) Fiat, 400 hp (300 kW) Liberty L-12 and the 360 hp (270 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines, with a total of 776 ordered before the end of the First World War. Of these, only aircraft powered by the Eagle engine, known as the Vimy IV, were delivered to the RAF.[15] Due to the diverse number of engines used, there are multiple conflicting official reports on the production numbers of each sub-variant of the Vimy.[16]

Operational history

RAF service

On 12 June 1918, according to aviation publication Flight International, the Air Board were to initially deploy the first production Vimy units as maritime patrol aircraft, equipped for anti-submarine warfare, and once this requirement had been satisfied, subsequent aircraft would be allocated to performing nighttime bombing missions from bases in France.[5] This had been due to a recently introduced policy under which the number of land-based aircraft allocated to anti-submarine patrols was to be vastly expanded, from 66 landplanes in November 1917 to a projected force of 726 landplanes, in which the newly-available Vimy would be a key aircraft due to its long range capabilities. During August 1918, the application of floats to the Vimy was studied, but it is not known if any aircraft were ever such fitted.[5]

By October 1918, only three aircraft had been delivered to the Royal Air Force (RAF), one of which had been deployed to France for use by the Independent Air Force. It had been envisioned that the Vimy would be able to conduct long range bombing missions into Germany, having the ability to reach Berlin from bases in France; however, the Armistice of 11 November 1918 had brought an end to the conflict before the Vimy could be used on any offensive operations.[17][7] Following the end of the conflict, the RAF rapidly contracted in size, which slowed the introduction of the Vimy.[18] The Vimy only reached full service status in July 1919 when it entered service with 58 Squadron in Egypt, replacing the older Handley Page 0/400.[19]

Throughout the 1920s, the Vimy formed the main heavy bomber force of the RAF; for some years, it was the only twin-engine bomber to be stationed at home bases in Britain.[18] On 1 April 1924, No. 9 Squadron and No. 58 Squadron, equipped with the Vimy, stood up, tripling the home-based heavy bomber force. On 1 July 1923, a newly formed Night Flying Flight, based at RAF Biggin Hill, equipped with the Vimy, was formed; during the general strike of 1926, this unit performed aerial deliveries of the British Gazette newspaper throughout the country.[18] Between 1921 and 1926, the type formed the backbone of the airmail service between Cairo and Baghdad.[18] The Vimy served as a front line bomber in the Middle East and in the United Kingdom from 1919 until 1925, by which point it had been replaced by the newer Vickers Virginia.[20]

Despite the emergence of the Virginia, which numerous Vimy squadrons were soon re-equipped with, the Vimy continued to equip a Special Reserve bomber squadron, 502 Squadron, stationed at Aldergrove in Northern Ireland until 1929.[20][18] The Vimy continued to be used in secondary roles, such as its use as a training aircraft; many were re-engined with Bristol Jupiter or Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar radial engines.[12] The final Vimys, used as target aircraft for searchlight crews, remained in use until 1938.[21]

Long-distance flights

The Vimy was used in many pioneering flights.

.jpg)

- The most significant was the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by Alcock and Brown in June 1919 (their aircraft is preserved in the London Science Museum);[22] This Vimy had been specially constructed to perform the flight, having been outfitted with additional fuel tanks in order to extend its range. The undercarriage was also revised; only one such aircraft was built.[23]

- In 1919, the Australian government offered £10,000 for the first All-Australian crew to fly an aeroplane from England to Australia. Keith Macpherson Smith, Ross Macpherson Smith and mechanics Jim Bennett and Wally Shiers completed the journey from Hounslow Heath Aerodrome to Darwin via Singapore and Batavia on 10 December 1919 (their aircraft G-EAOU is preserved in a museum in Smith's hometown Adelaide, Australia);[24][25] "The trip from Darwin to Sydney took almost twice as long as the flight to Australia."[26]

- In 1920, Lieutenant Colonel Pierre van Ryneveld and Major Quintin Brand attempted to make the first England to South Africa flight. They left Brooklands on 4 February 1920 in the Vimy G-UABA named Silver Queen. They landed safely at Heliopolis, but as they continued the flight to Wadi Halfa they were forced to land due to engine overheating with 80 miles (130 km) still to go. A second Vimy was lent to the pair by the RAF at Heliopolis (and named Silver Queen II). This second aircraft continued to Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia where it was badly damaged when it failed to take off.[24] Van Ryneveld and Brand then used a South African Air Force Airco DH.9 to continue the journey to Cape Town. The South African government awarded them £5,000 each.[11]

Vimy Commercial

The Vimy Commercial was a civilian version with a larger-diameter fuselage (largely of spruce plywood), which was developed at and first flew from the Joyce Green airfield in Kent on 13 April 1919. Initially, it bore the interim civil registration K-107,[27] later being re-registered as G-EAAV.[24]

The prototype entered the 1920 race to Cape Town; it left Brooklands on 24 January 1920 but crashed at Tabora, Tanganyika on 27 February.[24]

A Chinese order for 100 is particularly noteworthy; forty of the forty-three built were delivered to China, but most remained in their crates unused; only seven were put into civilian use.

Fifty-five military transport versions of the Vimy Commercial were built for the RAF as the Vickers Vernon.[28]

Role in the Second Zhili-Fengtian War

After the First Zhili-Fengtian War, 20 aircraft were secretly converted into bombers under the order of the Zhili clique warlord Cao Kun, and later participated in the Second Zhili-Fengtian War.[29]

During the Second Zhili-Fengtian War, these bomber versions of the Vimy Commercial were initially highly successful due to the low-level bombing tactics used, with the air force chief-of-staff of the Zhili clique, General Zhao Buli (趙步壢) personally flying many of the missions. However, on 17 September, returning from a successful bombing mission outside Shanhai Pass, General Zhao's bomber was hit by ground fire from the Fengtian clique in the region of Nine Gates (Jiumenkou, 九門口) and had to make a forced landing. Although General Zhao was able to make a successful escape back to his base, the bombers subsequently flew at much higher altitude to avoid ground fire, which greatly reduced their bombing accuracy and effectiveness.[29]

After numerous battles between Chinese warlords, all of the aircraft fell into the hands of the Fengtian clique, forming its First Heavy Bomber Group.[29] These bombers were in the process of being phased out at the time of the Mukden Incident and therefore were subsequently captured by the Japanese, who soon disposed of them.

Replicas

Apart from a replica transatlantic Vimy cockpit section built by Vickers for the London Science Museum in the early 1920s, three full-size replicas have also been built. The first was a taxiable replica commissioned by British Lion Films from Shawcraft Models Ltd of Iver Heath, Bucks; the planned film about Alcock & Brown's transatlantic flight was never made, but the model was completed and paid for. Its fate remains a mystery[30] although it appeared on static display at the Battle of Britain air display at RAF Biggin Hill in 1955 and may have been subsequently stored dismantled in East London until at least the late 1980s. The engine nacelles appear in the mine scene from the film 'Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D.', so it may not have been in good condition by then.

In 1969, an airworthy Vimy replica (registered G-AWAU) was built by the Vintage Aircraft Flying Association at Brooklands (this aircraft was first flown by D G 'Dizzy' Addicott and Peter Hoar but was badly damaged by fire that summer and was displayed until February 2014 at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London).[31][32] It is currently stored dismantled by the RAF Museum in Stafford.[31]

A second flyable Vimy replica, NX71MY, was built in 1994 by an Australian-American team led by Lang Kidby and Peter McMillan, and this aircraft successfully recreated the three great pioneering Vimy flights: England to Australia flown by Lang Kidby and Peter McMillan (in 1994),[33] England to South Africa flown by Mark Rebholz and John LaNoue (1999) and in 2005, Alcock and Brown's 1919 Atlantic crossing was recreated, flown by Steve Fossett and Mark Rebholz. The aircraft was donated to Brooklands Museum in 2006 and was kept airworthy in order to commemorate the 90th anniversaries of the Transatlantic and Australian flights until retired in late 2009. Its final flight was made by John Dodd, Clive Edwards and Peter McMillan from Dunsfold to Brooklands on 15 November 2009 and four days later, in just 18 hours, the aircraft was dismantled, transported the short distance to the Museum and reassembled inside the main hangar by a dedicated volunteer team. Two days later a special Brooklands Vimy Exhibition was officially opened by Peter McMillan, and this unique aircraft is now on public display there.

Variants

- F.B.27 Vimy

- Prototypes; four built, powered by two 200 hp (150 kW) Hispano-Suiza 8 piston engines..

- F.B.27A Vimy II

- Twin-engine heavy bomber aircraft for the RAF, powered by two 360 hp (270 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII piston engines.

- Vimy Ambulance

- Air ambulance version for the RAF.[34]

- Vimy Commercial

- Civilian transport version, powered by two 360 hp (270 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII piston engines.

- A.N.F. 'Express Les Mureaux'

- Vimy Commercial No.42 re-engined with 2x 370 hp (280 kW) Lorraine 12Da V-12 engines.

Operators

Military operators

Civil operators

- The Government of China (Vimy Commercial).

- Grands Express Aériens (Vimy Commercial).

- One aircraft.

- The Government of Spain (Vimy).

- Imperial Airways (Vimy Commercial).

- Instone Air Line (Vimy Commercial).

Aircraft on display

.jpg)

- Australia

- Vimy IV G-EAOU at Adelaide Airport[35]

- United Kingdom

- Vimy IV – Alcock & Brown's transatlantic aircraft at the Science Museum London.[36]

Specifications

Data from Profile Publications No. 005: Vickers F.B.27 Vimy[25]

General characteristics

- Length: 43 ft 7 in (13.28 m)

- Wingspan: 68 ft 1 in (20.75 m)

- Height: 15 ft 8 in (4.77 m)

- Wing area: 1,330 sq ft (123.56 m²)

- Empty weight: 7,104 lb (3,222 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 10,884 lb (4,937 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII piston engines, 360 hp (268 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 100 mph (161 km/h)

- Range: 900 mi (1,448 km)

- Service ceiling: 7,000 ft (2,134 m)

- Power/mass: 0.07 hp/lb (0.11 kW/kg)

Armament

- Guns: 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis Gun in Scarff ring in nose and 1 × in Scarff ring in mid-fuselage

- Bombs: 2,476 lb (1,123 kg) of bombs

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Bruce 1965, p. 3.

- ↑ Jarrett 1992, p. 9.

- ↑ Mason 1994, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bruce 1965, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Bruce 1965, p. 6.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce 1965, p. 7.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 4–5, 7.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruce 1965, p. 5.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 Bruce 1965, p. 12.

- 1 2 Bruce 1965, p. 9.

- 1 2 Bruce 1965, p. 10.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 6, 10.

- ↑ Mason 1994, p. 96.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Thetford 1992, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce 1965, p. 8.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 90.

- 1 2 Mason 1994, p. 98.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 93.

- ↑ Jackson 1988, p. 201.

- ↑ Bruce 1965, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson 1988, p. 202.

- 1 2 Bruce 1965, pp. 10, 12.

- ↑ "Vickers Vimy." Discover Collections: State Library of NSW. Retrieved: 4 December 2012.

- ↑ Andrews and Morgan 1988, p. 95.

- ↑ "The Vickers "Vimy-Commercial" Biplane." Flight, Volume XI, Issue 29, No. 551, 17 July 1919, pp. 936–941. Retrieved: 12 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 "我國最早航運機隊主力 -商用維美運輸機"(Vickers Vimy Commercial in Chinese language) sinaman.com. Retrieved: 15 March 2008.

- ↑ Aeroplane magazine, May 2010

- 1 2 "Vickers Vimy replica due to leave RAF Museum". Pilot. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Jackson 1988, p. 203.

- ↑ McMillan 1995, pp. 4–43.

- ↑ "The Vickers Vimy-Commercial Ambulance Machine." Flight, Volume XIII, Issue 11, No. 638, 17 March 1921, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ "History". Adelaide Airport. 5 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Ellis 2016, p. 161

Bibliography

- Andrews, C.F. and Eric B. Morgan. Vickers Aircraft since 1908, Second edition. London: Putnam, 1988. ISBN 0-85177-815-1.

- Bruce, J.M. Profile Publications No. 005: Vickers F.B.27 Vimy. Profile Publications Ltd., Leatherhead, Surrey. 1965.

- Ellis, Bruce. Wreck and Relics 25th Edition. Crecy Publishing Ltd, Manchester, England 2016. ISBN 978 191080 9037.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft 1919–1972: Volume III. London: Putnam, revised second edition, 1988. ISBN 0-85177-818-6.

- Jarrett, Philip. "By Day and By Night: Part Six." Aeroplane Monthly Volume 20, No. 11, November 1992, pp. 8–14. London: IPC.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber Since 1914. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- McMillan, Peter. "The Vimy Flies Again" National Geographic, Volume 187, No. 5, May 1995, pp. 4–43.

- Thetford, Owen. "By Day and By Night: Part Seven." Aeroplane Monthly, Volume 20, No. 12, December 1992, pp. 30–38. London: IPC.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Vickers Vimy." Biplanes, Triplanes and Seaplanes (Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2004. ISBN 1-84013-641-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vickers Vimy. |

- The Vickers Vimy-Commercial at Hendon, 1919

- Vickers Vimy preserved at Adelaide, South Australia

- RAF Museum

- Alcock and Brown's aeroplane at the London Science Museum

- Vickers Vimy online collection – State Library of NSW

- The Science Museum,South Kensington: Alcock and Brown's Vickers Vimy biplane, 1919

- National Geographic record of the 2005 re-enactment on the Atlantic flight