USS Liscome Bay

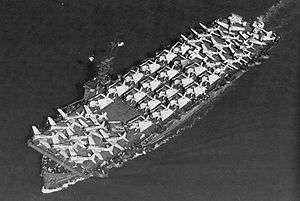

USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56), underway, 20 September 1943, with a load of SBD Dauntlesses, TBF Avengers and F4F Wildcats. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Liscome Bay |

| Namesake: | bay off the eastern coast of Dall Island |

| Awarded: | Kaiser Shipbuilding Company, Vancouver, Washington |

| Yard number: | 302[1] |

| Laid down: | 9 December 1942 |

| Launched: | 19 April 1943 |

| Sponsored by: | Mrs. Ben Moreell |

| Commissioned: | 7 August 1943 |

| Reclassified: | CVE, 15 July 1943 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | Lost in action, 24 November 1943 |

| General characteristics [2] | |

| Class and type: | Casablanca-class escort carrier |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | |

| Beam: |

|

| Draft: | 22 ft 4 in (6.81 m) (max) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 19 kn (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Range: | 10,240 nmi (18,960 km; 11,780 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 27 aircraft |

| Aviation facilities: | |

| Service record | |

| Part of: | United States Pacific Fleet (1943) |

| Commanders: | Captain I.D. Wiltsie |

| Operations: |

|

USS Liscome Bay (ACV/CVE-56), a Casablanca-class escort carrier during World War II, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for Liscome Bay in Dall Island in the Alexander Archipelago of Alaska. She was lost to a submarine attack by Japanese submarine I-175 during Operation Galvanic, with a catastrophic loss of life, on 24 November 1943.

Construction

Liscome Bay was laid down on 9 December 1942, under a Maritime Commission (MARCOM) contract, MC hull 1093, by Kaiser Shipbuilding Company, Vancouver, Washington; she was launched on 19 April 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Ben Moreell, wife of the Chief of the Navy's Bureau of Yards & Docks; she was named Liscome Bay on 28 June 1943, and assigned the hull classification symbol CVE-56 on 15 July 1943: she was acquired by the Navy and commissioned on 7 August 1943, Captain Irving D. Wiltsie in command.[3]

Service history

After training operations along the West Coast, Liscome Bay departed from San Diego, California, on 21 October 1943, arriving at Pearl Harbor one week later. Once additional drills and operational exercises were completed, the escort carrier set off on what was to be her first and last battle mission. As a member of Carrier Division 24 (CarDiv 24), she departed from Pearl Harbor on 10 November, attached to TF 52, Northern Attack Force, under Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, bound for the invasion of the Gilbert Islands.[3]

The invasion bombardment announcing the United States's first major thrust into the central Pacific began on 20 November, at 05:00. Just 76 hours later, Tarawa and Makin Islands were both captured.[3] Liscome Bay's aircraft had not yet taken part in any of the[4] 2,278 action sorties by carrier-based planes, which neutralized enemy airbases, supported US Army landings and ground operations in bombing-strafing missions, and intercepted enemy raids. With the islands secured, US naval forces began retiring.[3]

Sinking

On 23 November, the Japanese submarine I-175 arrived off Makin. The temporary task group, built around Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix's three escort carriers, Liscome Bay, Coral Sea and Corregidor, was steaming 20 mi (32 km) southwest of Butaritari Island at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph).[3]

At 04:30 on 24 November, reveille was sounded in Liscome Bay. Flight quarters was sounded at 04:50. The crew went to routine general quarters at 05:05, when flight crews prepared their planes for dawn launchings. Thirteen planes, including one forward on the catapult, had been spotted on the flight deck. These had all been fueled and armed. There were an additional seven planes in the hangar that were not fueled or armed. Since this was to be the first operations for Liscome Bay since leaving Pearl Harbor she still had her complete allowance of bombs still in the bomb magazine minus the bombs already loaded. This included nine 2,000-pound (910 kg) GP bombs, nine 1,600-pound (730 kg) AP bombs, 24 1,000-pound (450 kg) GP bombs, 96 500-pound (230 kg) GP bombs, 120 100-pound (45 kg) GP bombs, and 96 350-pound (160 kg) depth charges. In addition, she had 12 torpex-loaded aircraft torpedoes in the port side of the hangar aft.[4]

At about 05:10, a lookout stationed at the 40mm director on the gallery walkway at frame 160 starboard, reported over the telephone that he saw a torpedo headed for the ship.[4] The torpedo struck abaft the after engine room[3] and detonated the aircraft bomb magazine, located between frames 152 to 168, causing a major explosion which engulfed the ship and sent shrapnel flying as far as 5,000 yd (4,600 m).[5] Considerable debris fell on New Mexico, about 1,500 yd (1,400 m) distant from Liscome Bay. The explosion completely demolished and killed everyone aft of the forward bulkhead of the after engine room. The hangar deck aft of frame 110 and the flight deck aft of 101 were destroyed and missing. The forward part of the hangar was immediately engulfed in an intense fire, igniting the few remaining planes on the flight deck. All services, steam, compressed air, and firemain pressure were lost in the remaining portion of the ship. [4] "It didn't look like a ship at all", wrote Lieutenant John C. W. Dix, communications officer on Hoel, "We thought it was an ammunition dump... She just went whoom — an orange ball of flame."[5]

At 05:33, only 23 minutes after the explosion, Liscome Bay listed to starboard and then sank, carrying 54 officers and 648 enlisted men,[4] including Admiral Mullinix, Captain Wiltsie,[3] and Pearl Harbor hero Ship's Cook Third Class Doris Miller, down with her. Of the 916 crewmen, only 272 were rescued, by Morris, Hughes and Hull.

Including the sailors lost on Liscome Bay, American casualties in the assault on Makin Island exceeded the strength of the entire Japanese garrison. Future legal scholar Robert Keeton, then a Navy lieutenant, survived the attack.[6]

Awards

Liscome Bay received one battle star for her World War II service.[3]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kaiser Vancouver 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 DANFS 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 WAR DAMAGE REPORT No. 45 1944.

- 1 2 Hornfischer, p. 67.

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis. "Robert E. Keeton, 87, Author of Influential Law Treatises, Is Dead." New York Times 4 August 2007.

Bibliography

- "Liscome Bay". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Kaiser Vancouver, Vancouver WA". www.ShipbuildingHistory.com. 27 November 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "USS LISCOME BAY (CVE-56)". Navsource.org. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Hornfischer, J.D. The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors. p. 67.

- WAR DAMAGE REPORT No. 45. U.S. Hydrographic Office. 10 March 1944. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

Further reading

- James J. Fahey, Pacific War Diary: 1942–1945, The Secret Diary of an American Sailor, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1991. ISBN 0-395-64022-9

- James L. Noles, Jr., Twenty-Three Minutes to Eternity: The Final Voyage of the Escort Carrier USS Liscome Bay, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56). |