USS Illinois (BB-65)

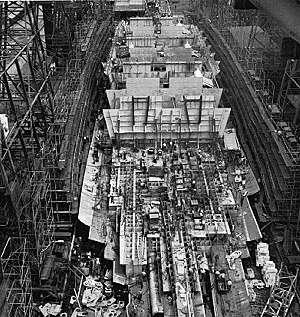

USS Illinois (BB-65) in July 1945, just weeks before construction was canceled | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Illinois |

| Namesake: | State of Illinois |

| Ordered: | 9 September 1940 |

| Builder: | Philadelphia Naval Shipyard |

| Laid down: | 6 December 1942 |

| Launched: | Canceled prior to launch |

| Struck: | 12 August 1945 |

| Fate: | Dismantled on builder's ways, September 1958 |

| General characteristics (as designed) | |

| Class and type: | Iowa-class battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 887 ft 3 in (270.43 m) |

| Beam: | 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) |

| Draft: | 35 ft 10 in (10.92 m) (full load) |

| Installed power: | 212,000 shp (158,000 kW) |

| Speed: | 33 kn (61 km/h; 38 mph) |

| Complement: | 151 officers, 2,637 enlisted |

| Armament: | |

| Armor: | |

| Aircraft carried: | 3 × Vought OS2U Kingfisher/Curtiss SC Seahawk floatplanes |

Illinois (BB-65) was an uncompleted battleship originally intended to be the first ship of the Montana class. However, the urgent need for more warships at the outbreak of World War II and the U.S. Navy's experiences in the Pacific theater led it to conclude that rather than battleships larger and more heavily armed than the Iowa class, it quickly needed more fast battleships of that class to escort the new Essex-class aircraft carriers being built. As a result, hulls BB-65 and BB-66 were reordered and laid down as Iowa-class battleships in 1942. As such, she was intended to be the fifth member of the Iowa-class constructed, and fourth navy ship to be named in honor of the 21st US state.

Conversion to the Iowa-class from the Montana-class would have allowed BB-65 to gain eight knots in speed, carry more 20-millimeter (0.79 in) and 40-millimeter (1.57 in) anti-aircraft guns, and transit the locks of the Panama Canal; however, this also left the ship with a reduction in her main battery from twelve 16-inch (410 mm) guns to nine, and without the additional planned armor.

Like her sister ship Kentucky (BB-66), Illinois was still under construction at the end of World War II. She was canceled in August 1945, but her hull remained as a parts hulk until she was broken up in 1958.

Background

The passage of the Second Vinson Act in 1938 cleared the way for construction of the four South Dakota-class battleships and the first two Iowa-class fast battleships (hull numbers BB-61 and BB-62). Hull numbers BB-63 and BB-64, cleared for construction in 1940, were to have been the final members of the Iowa class, while BB-65 and BB-66, also cleared in 1940,[1] were intended to be the first ships of the larger, more heavily armed Montana class.[2][3]

Originally, the Montanas were designed to return to the United States Navy's traditional battleship philosophy of maximum firepower and armor.[4] Considerations were also given to counter to the new battleships of the Empire of Japan, eventually known to be Yamato-class battleships, whose construction was shrouded by secrecy; furthermore, rumors of the Japanese ships' ability to carry guns of up to 18-inch (460 mm) were known at the time to the highest-ranking members of the United States Navy.[5] To achieve these goals, the United States Navy began designing a 45,000 ton "slow" battleship with maximum speed of 27-28 knots and an intended main battery of twelve 16-inch (406 mm) guns, three more than the Iowa-class. This battleship design took shape in the late-1930s and early-1940s and evolved into the 60,500-long-ton (61,500 t) Montana-class. She would also have a more powerful secondary battery of 5-inch (127 mm)/54 caliber Mark 16 dual purpose mounts, and an increase in armor designed to enable her to withstand the effects of enemy guns comparable to her own.[6][7][8]

The increase in the Montanas firepower and armor came at the expense of her speed and ability to utilize the Panama Canal, but transit between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans without having to round South America would have been eliminated through the construction of a third, much wider set of locks there. As the situation in Europe deteriorated in the late-1930s, concern arose over the possibility of the canal being put out of action by enemy bombing. Nevertheless, in 1939, construction began on the wider locks.[6][lower-alpha 1]

After the successes of carrier combat achieving air supremacy in both 1942's Battle of the Coral Sea, and, to a greater extent, Battle of Midway,[9][10] the Navy was forced to shift its building focus from battleships to aircraft carriers. As a result, construction of the fleet of Essex-class aircraft carriers had been given highest priority.[11] In the process, the United States found the high speed of 33 knots of the Iowas valuable; this allowed them to steam with the Essex-class while providing the carriers with maximum anti-aircraft protection.[9][12]

When BB-65 was redesignated an Iowa-class, she was assigned the name Illinois and reconfigured to adhere to the "fast battleship" designs planned in 1938, by the Preliminary Design Branch at the Bureau of Construction and Repair.[lower-alpha 2][13] Her funding was authorized via the passage of the Two-Ocean Navy Act by the US Congress on 19 July 1940, and she would now be the fifth Iowa-class built for the United States Navy.[13][14] Her contract was assigned on 9 September 1940, the same date as Kentucky.[15]

Construction

Illinois's keel was laid down at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, on 6 December 1942;[16] her projected completion date was 1 May 1945.[15] This amounted to a construction time of about 30 months. Based on wartime experience, she would have been tasked primarily with the defense of the US fleet of Essex-class aircraft carriers. In adherence with the Iowa-class design, Illinois would have a maximum beam of 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) and a waterline length of 860 ft (260 m), permitting a maximum speed of 33 knots (61.1 km/h; 38.0 mph).[2]

Like Iowa-class ships from Missouri (hull number BB-63) onward, the frontal bulkhead armor was increased from the original 11.3 in (287 mm) to 14.5 in (368 mm) in order to better protect against fire from frontal sectors.[17][18] Furthermore, like Kentucky, Illinois differed from her earlier sisters in that her design called for an all-welded construction, which would have saved weight due to increased strength over a combination riveted/welded hull used on the four completed Iowas. Additionally, engineers revised the torpedo protection system scheme of the Iowa-class to address some of the design flaws, such as excessive rigidity of the lower belt armor causing leakage in adjacent compartments in the event of a torpedo hit; the revised scheme had improvements such as removing knuckles in certain holding bulkheads; these alterations were estimated to improve both Illinois and Kentucky's torpedo protection by as much as 20%.[19][20] Funding for the battleship was provided in part by "King Neptune", a Hereford swine auctioned across the state of Illinois as a fundraiser, ultimately helping to raise $19 million in war bonds.[21]

Fate

Illinois's construction was put on hold in 1942, after the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway, while the Bureau of Ships considered an aircraft carrier conversion proposal for Illinois and Kentucky. As proposed, the converted Illinois would have had an 864-foot (263 m) long by 108-foot (33 m) wide flight deck, with an armament identical to the carriers of the Essex class: four twin 5-inch gun mounts and four more 5-inch guns in single mounts, along with six 40 mm quadruple mounts. It was abandoned after the design team decided that the converted carriers would carry fewer aircraft than the Essex class, that more Essex-class carriers could be built in the same amount of time to convert the battleships, and that the conversion project would be significantly more expensive than new Essexes. Instead, Illinois and Kentucky were to be completed as battleships, but their construction was given very low priority.[22]

Ultimately, the ship was canceled on 11 August 1945, when she was about 22% complete.[14] She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 12 August 1945.[23][24] Her incomplete hulk initially was retained on the belief that it could be used as a target in nuclear weapons tests. However, the some $30 million it would cost to complete the ship enough to be able to launch her proved too great and the plan was abandoned. She remained in the dockyard until September 1958, when she was broken up on the builder's ways.[14][25]

The ship's bell, inscribed USS Illinois 1946, is now at the Memorial Stadium at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The bell is on loan from the Naval Historical Center (Accession #70-399-A), Washington Navy Yard, Washington DC, to the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) at the university. The bell is traditionally rung by NROTC members when the football team scores a touchdown or goal.[26]

Notes

- ↑ The work proceeded for several years, and significant excavation was carried out on the new approach channels; but the project was canceled after World War II.[lower-alpha 3] Enlarging the Panama Canal Alden P. Armagnac. Popular Science. September 1940, Vol 137, No 3 Enlarging the Panama Canal for Bigger Battleships

- ↑ This was not the first time that changes to the Iowa class had been proposed: at the time the battleships were cleared for construction some policymakers were not sold on the U.S. need for more battleships, and proposed turning the Iowa-class ships into aircraft carriers by retaining the hull design, but switching their decks to carry and handle aircraft (This had already been done on the battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga). The proposal was countered by Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations. "BB-61 Iowa-class Aviation Conversion". Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- ↑ A third set of even wider locks—these ones 180 ft (54.86 m) in width, as opposed to the preexisting 110 ft (33.53 m)-wide locks and the 140 ft (42.67 m)-wide locks proposed by the WWII-era expansion project—was built much later, however, opening in 2016, although this was driven by increases in cargo ship size rather than warship size.

References

Citations

- ↑ Rogers 2006, pp. 7-8.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Chesneau 1980, p. 99.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, p. 317.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, p. 329.

- ↑ Czarnecki 2002.

- 1 2 Gardiner & Chesneau 1980, p. 100.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1995, p. 171.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, p. 239.

- 1 2 Discovery.

- ↑ Spring.

- ↑ Minks 2006.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, p. 327.

- 1 2 Johnston & McAuley 2002, pp. 108–123.

- 1 2 3 Dulin & Garzke 1976, p. 137.

- 1 2 Whitley 1998, p. 310.

- ↑ Whitley 1998, p. 306.

- ↑ Sumrall 1988, p. 129.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, p. 314.

- ↑ Armor.

- ↑ Sumrall 1988, p. 132.

- ↑ Py-Lieberman 2002.

- ↑ Garzke & Dulin 1995, p. 288.

- ↑ DANFS Illinois (Battleship No. 7).

- ↑ NVR Illinois (BB 65).

- ↑ Whitley 1998, p. 311.

- ↑ Herman 2007.

Bibliography

Print sources

- Dulin, Robert O., Jr.; Garzke, William H. (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-099-0. OCLC 2414211.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-715-9. OCLC 12214729.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9. OCLC 18121784.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O., Jr. (1995). Battleships: United States Battleships 1935–1992. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-174-5. OCLC 29387525.

- Johnston, Ian; McAuley, Rob (2002). The Battleships. London: Channel 4 Books (an imprint of Pan Macmillan). ISBN 978-0-7522-6188-1.

- Sumrall, Robert (1988). Iowa Class Battleships: Their Design, Weapons & Equipment. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-298-7. OCLC 19282922.

- Whitley, M.J. (1998). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour. ISBN 978-1-85409-386-8.

- "Spring Styles" Book # 3 (1939–1944)–(Naval Historical Center Photo #: S-511-54) "Aircraft Carrier, Converted from BB 61-66 Class". DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER. 15 February 2005. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

Online sources

- "Illinois". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "USS Illinois (BB 65)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy. 22 July 2002. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Herman, Richard, Chancellor (October 2007). "Illinois in Focus". Illinois On Our Watch. Public Affairs for the Office of the Chancellor and the University of Illinois Alumni Association. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Minks, R. L. (1 September 2006). "Montana class battleships end of the line". Sea Classics. Challenge Publications. 39 (9). Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Rogers, J. David (2006). "Development of the World's Fastest Battleships" (PDF). Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Czarnecki, Joseph (21 August 2002). "What did the USN know about Yamato and when?". Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- "Iowa Class: Armor Protection". Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Py-Lieberman, Beth (February 2002). "Any Bonds Today?". Smithsonian.

Video sources

- "Top Ten Fighting Ships: Iowa Battleship". Combat Countdown. The Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012.

Further reading

- Barrett, John (1913). The Panama Canal, what it is, what it means. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union. OCLC 244998670.

- McCullough, David G. (1977). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-22563-6. OCLC 2695090.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Illinois (BB-65). |

- Iowa Class (BB-61 through BB-66), 1940 & 1941 Building Programs

- Photo gallery of Illinois (BB-65) at NavSource Naval History