Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad

Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad locomotive #550 in Export, PA | |

| Reporting mark | TCKR |

|---|---|

| Locale | Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania |

| Dates of operation | 1982–2009 |

| Predecessor | Turtle Creek Branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad[1] |

| Successor | Westmoreland Heritage Trail |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 10.7 miles (17.2 km) |

| Headquarters | Export, Pennsylvania |

Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

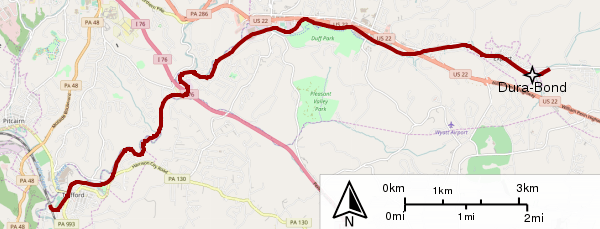

The Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad (reporting mark TCKR) was a short line railroad that operated in Pennsylvania. It was a wholly owned subsidiary of the Dura-Bond Corporation of Export, Pennsylvania. The TCKR was created when Conrail (the successor to the Pennsylvania Railroad) abandoned the line in 1982. When it last was operational, the line ran from Export down the Turtle Creek valley until it joined with Norfolk Southern Railway's Pittsburgh Line at Trafford, Pennsylvania.

Founding and acquisition by Pennsylvania RR: 1886-1982

The Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad traces its origins back to 1886, when George Westinghouse chartered what was then called the Turtle Creek Valley Railroad with the hopes of exploiting the natural gas fields in Murrysville. At its peak the line would extend from Westinghouse's facilities in Trafford all the way through Saltsburg, and its primary cargo would be not gas but coal. Passenger service to and from Pittsburgh and points west was also popular before the age of the automobile caused its decline. Coal shipments declined as well as mines closed, and by the beginning of the 1980s Conrail, the new owner of the line, was looking to abandon it.[4][5]

Sale from Conrail to Dura-Bond: 1982

In November 1981 Conrail announced intention to abandon its unprofitable Turtle Creek Valley Line.[6] At the time several businesses relied on it for shipments, including Dura-Bond, an Export based protective coating company owned by the Norris family. Wayne Norris then sized up the company's situation: "Losing this line would be inconvenient for the other companies, but it would be devastating for us". He noted that Dura-Bond needed to move large steel products too big and heavy to ship by truck, a number of truck strikes had occurred in the area, and his company needed a reliable, competitive transportation alternative.[7] They were faced with a choice: move their company to a new location served by rail, subsidize Conrail's existing operations, or purchase the railroad. After discussing their options, Dura-Bond decided to purchase the railroad outright, taking on other businesses along the line as paying customers. They renamed the railroad the "Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad", and would own and operate it themselves as a privately owned subsidiary company.[8]

To defray some of the start up costs, Dura-Bond received a $313,240 grant from the commonwealth of Pennsylvania.[9] Governor Dick Thornburgh, who traveled to Export for the newly acquired railroad's opening ceremony, justified the grant, remarking that the rail service would preserve more than 700 industrial jobs in Westmoreland County.[7] The Westmoreland County Industrial Development Authority also backed the project with low interest revenue bonds.[9] The purchase price of the line would be $125,000,[10][11] but this relatively low number reflected something all of the parties in the deal knew: the track was in very poor condition. Dura-Bond secured a bank loan to help pay the additional costs that it knew would soon come.[12]

The newly purchased short-line railroad began operations in June 6, 1982 and experienced 12 derailments in its first month. Since the trains were limited to a maximum of 10 miles per hour, these were not necessarily as dramatic as the word "derailment" can imply, but were still disruptive enough for Dura-Bond to quickly hire a contractor to perform two months worth of track repair on an expedited basis. In addition to its general state of disrepair that came from decades of neglect, the track was also too steeply banked around its bends, causing the TCKR's relatively slow, heavy trains to exert too much pressure on the inner rail as they went through turns. Track rehabilitation costs would total $418,000 in the first year, when the railroad lost money, and $225,000 in the second year, when it hoped to break even.[6] These were anticipated costs, as Dura-Bond had committed to operating the rail line for at least two years and could not sell it for at least five as conditions of the acquisition.[7]

Short line operations: 1982-2009

A Norris family engineer summarized the company's key to its plan for turning the railroad to profitability, "Conrail needed a seven man crew to run the line. We do it with two men and a dog."[7] In addition to the engineer's pit-bull, the TCKR employed 4 persons, nominally two engineers and two brakemen.[13] They would do everything including driving the trains, keeping the railroad's 1940s era locomotives running, and maintaining the track. They also had the skills and equipment to re-rail minor derailments, as well as replace damaged rail ties using only hand tools if need be.[14]

As many as three round trips per day were possible on the line,[6] and Dura-Bond believed that trains of up to 10 cars could be safely transported.[7] Trains running 3-5 times per week,[14] averaging 4 cars per train[11] would come to be described as typical. A routine daily shipment began with Conrail dropping off a train in Trafford. Next Conrail would pick up a train of empty cars to be returned that had been previously left there by the TCKR. Later that day a TCKR locomotive would pick up the loaded train that had been left by Conrail and take it to Murrysville and/or Export for distribution to customers.[14] Cargo could include steel products, lumber, aluminum and rubber,[15] and single train could contain cars destined for multiple different locations. Sidings positioned along the single track in Trafford, Murrysville and Export made it possible for a TCKR locomotive to run around a train parked at any of those places, allowing it to detach cars from the train and push them to their individual recipients. Once deliveries had been made, the process would be reversed, as the short line's locomotive would gather and return empty cars to be towed back to Trafford where they would be picked up again by Conrail.[14] The TCKR's staff promised to work to keep the freight cars moving, stating that the cars "cost you money" when just sitting on a siding.[7] This won praise from the customers; two that were interviewed after the first year Dura-Bond owned the railroad commented that service had improved dramatically. One noted that shipments which could be delayed over a week on the transfer track when Conrail owned and operated the line were arriving the same day under the new local ownership and management.[6]

Despite the positive reviews and the efforts to expand the railroad's customer base,[6] the number of shippers reported on the line was at its highest when it first began operations, and would decline slowly over the next three decades. A preliminary report indicated that the newly acquired short-line had 10 customers, which, together with Dura-Bond, would total 11 patrons of the railroad. These were Beckwith Machinery, Building Components, Delmont Builders, 84 Lumber, Export Tire, Gateway Packaging, J&M Machinery, Long Mill Rubber, National Aluminum and Weyerhaeuser.[9] A total of 9 shippers were reported for the TCKR later in 1982[10] and 1983.[6] This had dropped again to 7 by 1984,[15] 5 in 1991,[14] and 4 in 1996.[16] In 2009 this number had dwindled to just 2: Dura-Bond itself and the lumber company Weyerhaeuser,[17] which had long been the railroad's biggest customer.[6][14]

Reports do not state with certainty when the railroad was turning a profit and when it was operating at a loss, but they do give some clues. When it first started operations in 1982, the company estimated it would be hauling 500-1000 cars per year at first, and would eventually have to haul "about 1500 cars a year" to turn a profit, charging $250 per car.[7] In 1991 about 500 cars/year was the reported haul; circa 1996 it was again nearly 500;[18] in 1999 it was about 700 cars per year.[11] Between those years Wayne Norris commented that his railroad was making enough money to pay for its basic maintenance, but not enough to replace a locomotive.[13] In 2009 an engineering survey indicated that only 150 cars per year were traveling over the railroad's bridges.[3] Norris attributed part of the drop off in business to the closure of Pittsburgh based steel mills.[19]

The railroad was kept running despite its apparent lack of profits. This was partly out of the need to ship materials to the railroad's parent company, but something less tangible may have also factored in. When his company first purchased the railroad, Wayne Norris admitted nostalgia played "a small role" in his decision to buy and operate it.[7] His words shed further light on this: "I was born and raised here in Export. I remember steam engines rolling through here. The trains were a part of our lives..I'm proud to be running a piece of Turtle Creek Valley history...Coal gave this borough its name..I'd read somewhere that a community suffers psychologically when it loses its rail service, and I believe there's some truth in it."[7][12]

The flood, end of service and conversion to rail-trail: 2009-2019

On the night of June 16–17, 2009 a powerful storm struck western Pennsylvania causing flash flooding along many streams and creeks, including Turtle Creek. Flooding in the borough of Export was particularly bad; its mayor commented that he had not seen water so high since the 1960s. In addition to damaging Dura-Bond's main facility, the water washed out five feet of the embankment that the Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad rested on.[20] Dura-Bond reported approximately $1 million in uninsured losses in addition to $1/4 million in losses to its railroad.[21] Governor Ed Rendell requested federal aid to deal with the impact or the storms, however this request was denied as the damages were not determined to be of such severity and magnitude to exceed the ability of state and local agencies to deal with them.[22] The flooding caused an extended outage of rail service, during which the only remaining customer on the line made arrangements to have rail cars sent to their facility via truck.[23]

The rails become a trail

The Regional Trail Corporation had long expressed interest in creating a rail-trail along the path of the TCKR, though initially the railroad's owners did not share this interest.[24] Sensing that the flood may have changed this, in 2011 the RTC and Westmoreland County put together an extensive plan to convert the railroad to a greenway.[25] In 2013 the TCKR officially filed for a discontinuation of service,[26] having previously acknowledged that service actually ended in 2009.[27] Soon thereafter, an agreement was finalized to sell most of the railroad to Westmoreland County for the appraised value of $863,000.[28] Dura-Bond president Wayne Norris acknowledged that continuing to operate the railroad would result in "a lot of flood related costs", noting a general trend of water flowing into the Turtle Creek valley more rapidly than in the past and attributing the increased runoff to increased suburban development in the watershed.[8] As of September 2017, the tracks have been removed from most of the railbed, and several miles of the western section have been made into an extension of the Westmoreland Heritage Trail, with the remaining eastern section scheduled for trail completion by 2019.[29]

Rolling Stock: Locomotives and Caboose

Before acquisition of the railroad, Dura-Bond already owned a small 300 horsepower 44-ton Whitcomb Co. switcher which it used to handle cars in the railyard at its facility;[6] it would later acquire a comparable General Electric 50-ton switcher to take over these duties.[14] But to operate the length of the railroad, the company would need some more powerful locomotives to haul up to 10 fully loaded cars up the steepest section of the track, reported to be a 2 percent gradient section in Murrysville. So in May 1982 the new railroad company purchased from the Johnstown and Stony Creek Railroad a 600 h.p. 100-ton switcher, model EMD SW1 built in August 1949,[18] which became TCKR engine #462.[6] Included as part of the $44,000 price of this locomotive was a cupola caboose, which the seller insisted had to be taken along with the engine as part of a two-for-one deal.[11] In 1985 the railroad purchased from the Union Railroad what it would dub TCKR engine #550, a 110-ton[18] 1200 h.p. model. A documentary video indicates TCKR 550 was manufactured in 1947,[14] while a 1996 railway guide[18] and railfans[30] state that it was built in October of 1949. These same two sources identify Engine 550 as a model EMD NW2, but it is listed as a model EMD SW7 in a 2006 official filing with the Surface Transportation Board.)[31] These two switch engines, both originally manufactured for the Union Railroad, would remain with the TCKR throughout the rest of its operations. Engine 462 was described as the primary workhorse of the railroad, with engine 550 also seeing occasional duty.[14]

The caboose bundled in the deal that acquired TCKR 462 was reportedly built in either 1927,[6] 1937[14][7] or 1939,[19] and given the name TCKR 9 by its new owner.[31] The company originally announced intentions to use this car to serve as a lookout at the end of its trains. But the 1980s would be a time when freight operators in the US were phasing out this traditional role of the caboose, and a documentary video of the Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad produced just after this decade showed many of its freight trains in operation, but none with a caboose in tow.[14] By 1999, TCKR 9 was spending most of its days parked near Old William Penn Highway in Export, serving as "a symbol of days gone by".[11] Dura-Bond did continue to maintain the caboose in rail-worthy condition for the special occasions on which it would see use, such as transporting Santa Claus during Export's Christmas celebrations.[32]

When it was decided that the line would be discontinued, new homes would be found for some of the equipment that once worked the tracks. In August 2014, engine 462 was moved to Dura-Bond's Duquesne facility, with the other engine remaining behind at its Export plant.[33] The company's caboose was thoroughly restored by Dura-Bond and donated to the Export Historical Society; it now sits on what remains of the TCKR track in downtown Export.[19]

References

- ↑ Boucher, John Newton; Jordan, John Woolf (1906). History of Westmoreland county, Pennsylvania, Volume 1. New York: The Lewis publishing company. p. 284.

- ↑ No. 9756 Track Chart, PRR Central Region, Pittsburgh Division Branches (PDF). Pittsburgh, PA: Pennsylvania RR Co. Dec 31, 1951.

- 1 2 Laman, Jeffrey; Guyer, Robert C. (Feb 1, 2010). Conditional Assessment of Short-line Railroad Bridges in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

- ↑ Trafford Borough 75th Anniversary Souvenir Book. Trafford, PA: Diamond Jubilee Committee. 1979.

- ↑ Richmond, Charles (July 15, 2004). Pennsylvania Historical Resource Survey (PDF). Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Bureau of Historic Preservation.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bach, Howard A. (December 10, 1983). "Faced With Rail Service Cutoff, Family Acquires, Runs Short Line". Altoona Mirror (Page 24).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bowman, Lee (June 10, 1982). "Tiny Railroad Gets On Track". Pittsburgh Press.

- 1 2 Varine, Patrick (July 23, 2015). "Turtle Creek short-line rail marks 125th anniversary". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

- 1 2 3 "New Westmoreland Rail Service Unveiled". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (PG East, Page 2). June 10, 1982.

- 1 2 Gibb, Tom (August 7, 1982). "Keeping State Business Online: Revival Of Abandoned Rail Picks Up Momentum". Altoona Mirror. p. 15, 19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hoffman, Ernie (April 7, 1999). "End of the line for Turtle Creek caboose". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Page 136).

- 1 2 Smith, Helene (1986). EXPORT: A Patch of Tapestry out of Coal Country America. Greensburg, PA: McDonald/Swärd Publishing Company. p. 210-211. ISBN 0945437005.

- 1 2 McKay, Jim (June 16, 1996). "Short lines are in it for the long haul - Off the beaten track". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pages C1-C4).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bluman, Allan R.; Bluman, Allan G.; Emry, Stu; Norris, Jim; Rubright, Charley; Karas, Luke (1991). "The Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad : A Short Line Operation". (Video, 50min). Box Office Productions.

- 1 2 "Fears of job, service cuts grow as Conrail sale nears". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pages 1, 10–11). September 5, 1984.

- ↑ "$hort Line $uccess - Railroads pick up the slack left by bigger companies". Altoona Mirror (Page C8). July 14, 1996.

- ↑ "Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad". Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis, Edward A. (1996). American Shortline Railway Guide. Kalmbach Publishing. p. 315. ISBN 0-89024-290-9.

- 1 2 3 Varine, Patrick (August 10, 2016). "Refurbished caboose to debut at Export Ethnic Food & Music Festival". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

- ↑ Gazarik, Richard (June 20, 2009). "Westmoreland officials assess damage while residents salvage what they can". Greensburg Tribune-Review.

- ↑ "Governor Rendell Signs Disaster Emergency Proclamation; Requests Federal Aid for Allegheny, Westmoreland Counties". PR Newswire (USA). June 29, 2009.

- ↑ Federal Emergency Management Agency (September 3, 2009). "Pennsylvania Severe Storm – Denial of Appeal" (PDF).

- ↑ Rico, Martha (October 30, 2014). EMPLOYER STATUS DETERMINATION Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad, Inc. (TCIR) (PDF).

- ↑ Scott, Rebekah (September 24, 2003). "Trail Group Won't Let Train Derail Plan For Link in Allegheny Passage". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ Mackin Engineering (February 2011). Turtle Creek Greenway Plan.

- ↑ Wilson, Richard (September 3, 2013). Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad, Inc. - Discontinuance of Service Exemption- In Westmoreland County, PA; STB Docket No. AB-825 (PDF).

- ↑ "DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Surface Transportation Board [Docket No. FD 35678] Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad, Inc.— Acquisition and Operation Exemption—Consolidated Rail Corporation" (PDF). Federal Register. 77 (208): 65446. October 26, 2012.

- ↑ Means, Tim (Feb 13, 2014). "Westmoreland County set to buy Turtle Creek railroad". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ http://www.murrysvilletrails.org/tc.htm

- ↑ "Turtle Creek Industrial RR.Incorporated Photographic Roster". rrpicturearchives.net. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- 1 2 Alvord, Robert (October 4, 2006). Memorandum of Security Agreement (PDF).

- ↑ Carmichael, Allison (December 9, 1999). "Holiday Lanterns to Light up the Streets". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Page E-4).

- ↑ "(title unknown)". Delmont Salem News (Volume 46, Number 55). August 27, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad. |

- Turtle Creek Industrial Railroad archived on Aug 21, 2009 from Dura-Bond.com/railroad.html