Turin–Lyon high-speed railway

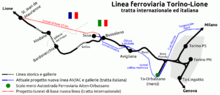

The Turin–Lyon high-speed railway is a planned 270 km (170 mi)-long, 220 km/h (140 mph) railway line[1] that will connect the two cities and link the Italian and French high-speed rail networks. The core of the project is a 57.5 kilometres (35.7 mi) base tunnel crossing the Alps between Susa valley in Italy and Maurienne in France.[2] The tunnel will be one of the longest rail tunnels in the world, with the 57.1 km Gotthard Base Tunnel, and it represents one third of the estimated overall cost of the project.

Like the Swiss NRLA project, the line aims to both transfer freight traffic across the Alps from trucks to rail and provide faster passenger transport. Its design speed of 220 km/h (140 mph) is slightly below the 250 km/h (160 mph) threshold used by the European Commission to define high-speed railways,[3] and the line is therefore part of the TEN-T Trans-European conventional rail network within its "Mediterranean Corridor"—previously "Corridor 6". The new line will considerably shorten the journey times, and its reduced gradients and much wider curves compared to the existing line will also allow heavy freight trains to transit between the two countries at 100 km/h (62 mph) and with much reduced energy costs.

The project has been criticized for its cost, because traffic (both by motorway and rail) was decreasing,[4] for potential environmental risks during the construction of the tunnel,[5] and because airplanes would still, after including time to and from the airport and through security, be slightly faster over the Milan-Paris route.[6] A 2012 report by the French Court of Audit questioned the realism of the costs estimates and traffic forecasts.[7]

Civil engineering work started with the construction of access points and geological reconnaissance tunneling.[8] Actual construction of the line was initially planned to start in 2014–2015,[9] but funding was delayed. The project was finally approved in 2015 for a cost of €25 billion, of which €8 billion is for the base tunnel.[10] The ratification of the corresponding treaty between the two countries by their respective parliaments concluded with a 26 January 2017 vote of the French Senate,[11] and an invitation to tender for detailed construction studies for the French side of the tunnel was published in late 2016.[12] Construction has yet to start officially, but the 9 km reconnaissance gallery that is being tunneled from Saint-Martin-de-la-Porte towards Italy is bored along the axis of the south tube of the tunnel and at its final diameter.[13] In late-December 2016, that reconnaissance tunnel encountered a geologically difficult zone of water-soaked fractured coal-bearing schists, and for several months made only very slow progress through it.[14] Tunneling passed this zone in Spring 2017 after injecting 30 tons of reinforcing resin,[15] and advances again at nominal speed.[16] As of August 2018, it is 50% complete.[17] Construction of the base tunnel is expected to start formally in 2018 and to take approximately 10 years.

Preliminary studies

The worthiness of the new line was the subject of heated debate, primarily in Italy, but later in France as well. After a 2005 attempt to start reconnaissance work near Susa (Italy) resulted in violent confrontations between opponents and police, an Italian governmental commission was set up in 2006 to study all the issues.[18] The work of the commission between 2007 and 2009 was summarized into seven papers (Quaderni). An eighth summary paper focused on cost–benefit analysis was unveiled in June 2012 but criticized by some experts for contents and for publication timing.

Test drilling found some internally stressed coal-bearing schists that are poorly suited for a tunnel boring machine, and old-fashion Drilling and blasting will be used for the corresponding 5 km section close to the French portal.[19]

The existing conventional line

Since 1872, the Turin–Modane railway connects Turin with Lyon via the 13.7 km (8.5 mi)-long high-altitude (mean tunnel altitude 1,123 m or 3,684 ft) Fréjus Rail Tunnel.[20] This initially single-track line was doubled and electrified in the early 20th century, and its Italian side was renovated between 1962 and 1984, and again between 2001 and 2011.[21] This historical line has a low maximum allowed height, and its sharp curves force low speeds. Its very poor profile, with a maximum gradient of 30‰, additionally requires doubling or tripling the locomotives of freight trains.

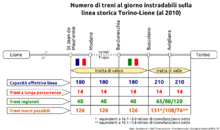

The characteristics of the line vary widely along its length. The Osservatorio (see References) divides the international and Italian sides into four sections:

- Modane - Bussoleno (Frejus tunnel and high valley section)

- Bussoleno - Avigliana (low valley section)

- Avigliana - Turin (metropolitan section)

- Turin node (urban section)

The first section comprises the Fréjus tunnel. Its lowest tunnel ceilings, highest elevation, sharpest curves, and steepest gradients, make this section the limiting factor on the overall capacity of the line. Its maximum capacity has been calculated as 226 trains/day, 350 days/year,[22] using the CAPRES model.[23] The study foresees a traffic of 180 freight trains per day. This value has to be lowered to about 150 freight trains per day due to logistical inefficiency, since the traffic flows between the two countries are asymmetric. A similar analysis for the whole year leads to a total of about 260 peak days per year.[24] These conditions define a maximum transport capacity per year of about 20 million tonnes when accounting for inefficiencies, and an absolute limit of about 32 million in "perfect" conditions.[25]

Additional traffic limitations stem from the impact of excessive train transit on the population living near the line. About 60,000 people live within 250 m (820 ft) of the historical line, and would object to the noise from late-night transits.[26]

In 2007 the conventional line was used for only one-third of its total capacity.[27] This low use level was in part because restrictions such as an unusually low maximum allowable train height and the very steep gradients (26-30‰) and sharp curves in its high valley sections discourage its use. A 2018 analysis found the line actually used at close to its maximum capacity, largely because that capacity has been significantly reduced by new safety rules on train crossings in the tunnel.[28]

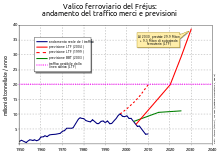

Traffic predictions

Future freight traffic from analysis of current data and macroeconomic predictions are summarized in the following table (in million tons per year):[29]

| Without the new line | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Alps – Total | 144.0 | 264.5 | 293.4 | 2.8% |

| Alps – Rail | 48.0 | 97.7 | 112.5 | 3.3% |

| Modane corridor – Total | 28.5 | 58.1 | 63.8 | 3.1% |

| Modane corridor – Rail | 6.5 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 3.6% |

| With the new line | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Alps – Total | 144.0 | 264.5 | 293.4 | 2.8% |

| Alps – Rail | 48.0 | 111.4 | 130.7 | 3.9% |

| Modane corridor – Total | 28.5 | 63.5 | 76.5 | 3.9% |

| Modane corridor – Rail | 6.5 | 29.5 | 39.4 | 7.2% |

| Heavy vehicles (thousand per year) | 2004 | 2025 | 2030 | Annual growth 2004-2030 |

| Without the new line | 1,485 | 2,791 | 3,121 | 2.9% |

| With the new line | 1,485 | 2,244 | 2,447 | 1.9% |

Promoters of the new line predict that it will about double rail traffic on the Modane corridor compared to the reference scenario (without the construction of the new line). It should be noted that traffic predictions of even the early traffic of major rail infrastructures are intrinsically uncertain, with well-known examples of both overestimates (e.g. the Channel tunnel[30]) and underestimates (e.g. the TGV Est[31]). Anyway, some experts disagree with the necessity for a new line connecting France and Italy on the Modane corridor, quoting wide margins for increase in traffic on the old line. Rather than as a natural consequence of faster transit times and a lower price for freight shipping (due to reduced energy use thanks to a much flatter profile, but without necessarily taking into account the full construction cost of the new line), they propose to increase rail traffic by coupling additional renovation of the existing rail infrastructure with sufficiently high financial incentives for rail transport and/or sufficiently heavy tolls and taxes on road transport. The political realism of such taxes is however questionable, as demonstrated by the 2013 violent protests against a trucking ecotax in France. Moreover, 2018 studies found that the existing line actually is close to saturation, largely because modern safety regulations on train crossings in the tunnel have significantly reduced its maximum capacity.[32] The construction of a brand-new line will also make the older infrastructure fully available for regional and suburban services, which is an important consideration near the congested Turin node. It will also allow higher safety standards.[33]

The new line

The new railway line will have a maximum gradient of 12.5‰, compared to 30‰ over 1 km (0.62 mi) of the old line, a maximum altitude of 580 m instead of 1,338 m, and much wider curves. This will allow heavy freight trains to transit at 100 km/h (62 mph) and passenger trains at a top speed of 220 km/h (140 mph), and will also sharply reduce the energy used.[34] The construction of the full high-speed line will cut passenger travel time from Milan to Paris from seven hours to four, becoming time-competitive with plane travel for town-center to town-center travel.[6]

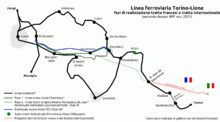

The line is divided into three sections constructed under distinct managements:

- the French section between Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne and the outskirts of Lyon will be built under SNCF Réseau management;

- the Italian section italienne between the Bussoleno (Susa valley) and Torino is under RFI ;

- the international section between Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in Savoie and Bussoleno, which includes the Mont d'Ambin Base Tunnel. It is managed by Tunnel Euralpin Lyon Turin (TELT SAS), a joint venture of RFI and SNCF which replaced Lyon Turin Ferroviaire.

French Section

The French section of the new line is planned with eventually separate paths for passengers and freight between Lyon and the Maurienne valley.

The passenger line will link the LGV Sud-Est (through a connection South of gare de Lyon-Saint-Exupéry) and the downtown Lyon stations to both Italy and Chambéry. It will connect near Chambéry to the Annecy via Aix les Bains and the Bourg Saint-Maurice via Albertville lines. The time gain from Paris or Lyon to Aix-les-Bains or Chambéry will be almost 45 minutes, and almost an hour to Annecy. The line may also be used to offload the saturated Lyon-Grenoble line from its TGV traffic, making space there for much needed additional local trains.

The freight line will start from a connection to the future Lyon rail freight bypass, follow the A43 freeway, and pass South of Chambéry through a tunnel under the Chartreuse mountains. That tunnel will eventually have two 23 km-long tubes, but it will initially be single-track. The line will then reach Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne through a second 20 to 23 km tunnel under the Belledonne mountains. The separate freight line will divert the freight traffic away from Aix-les-Bains and Chambéry, and from the shores of the Lac du Bourget where a freight accident on the existing line could catastrophically pollute this large natural freshwater reservoir.

Italian Section

The path of the Italian section was adopted in August 2011 by the Italian government, after extensive 2006-2011 consultations headed by Government Commissary Mario Virano within the "Italian Technical Observatory". In the Susa valley the new path sidesteps through additional tunneling the strong opposition to a previous planned path on the left bank of the Dora Riparia, which would have needed a viaduct in Venaus and a tunnel in Bussoleno.

International Section

The international section of the Lyon-Turin line spans about 70 km between Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in Savoie and Bussoleno in Piemonte. The 57.5 km Mont d'Ambin base tunnel is the major engineering work of the future Turin-Lyon line, and is being dug at the base of the Mont d'Ambin. An underground service and rescue train station is planned around the half-way point of the tunnel, East of Modane.

No TAV movement

No TAV is an Italian movement against the construction of the line.[35] The name comes from the Italian TAV acronym for Treno Alta Velocità, high speed train. The movement's first demonstrations date back to 1995, but it became widely recognized during protests in 2005 and in the following years. Some No TAV protests included disruption of highway traffic and violent clashes with police.[36]

The movement generally questions the worthiness, cost, and safety of the project, drawing arguments from studies, experts, and governmental documents from Italy, France, and Switzerland. It deems the new line useless and too expensive, and decries its realization as driven by construction lobbies. Its main stated objections are:

- Low level of saturation on the Frejus rail tunnel and stable or decreasing traffic also on Fréjus Road Tunnel

- Economical feasibility in doubt due to high costs

- Danger of environmental disasters

- Concerns about health, due to the hypothetical presence[37] of uranium and asbestos in the mountains where the tunnel is to be bored, though the extensive reconnaissance tunneling has found none to date.

Members of the movement have summarized their ideas against the construction of the new line in a document containing 150 reasons against it[38] and in a wide number of specific documents and meetings.[39]

Critics of the No TAV movement, by contrast, characterize it as a typical NIMBY movement.[40]

See also

Notes

- ↑ (in Italian) Nuova linea Torino-Lione parte comune tratta italiana - Progetto in variante - Studio d'impatto ambientale - sintesi non tecnica 9-7-2010 (document PP2 C3C TS3 0105A AP NOT)

- ↑ "The Alpine tunnels". LTF. Archived from the original on 31 October 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Decision No 661/2010/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 July 2010 on Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ↑ http://www.lemonde.fr/pollution/article/2016/05/05/l-atlas-de-la-france-toxique-dresse-l-inventaire-des-sites-les-plus-pollues_4914519_1652666.html

- 1 2 "Dichiarazioni alla stampa del Presidente Monti al termine della riunione sui lavori di realizzazione della Tav tratto Torino-Lione" [Press conference by president Mario Monti]. Italian Government. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ , "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ↑ "Close-up on works". LTF. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ http://www.ltf-sas.com/pages/articles.php?art_id=79%7CCalendario

- ↑ Lyon-Turin project

- ↑ http://www.lemonde.fr/planete/article/2017/01/26/l-accord-franco-italien-pour-la-ligne-ferroviaire-lyon-turin-definitivement-adopte_5069643_3244.html

- ↑ http://www.telt-sas.com/fr/tunnel-de-base-du-mont-cenis-lancement-du-premier-appel-doffres/

- ↑ "Manuel Valls inaugure le tunnelier Federica au chantier du Lyon-Turin à Saint-Martin-La-Porte". LTF. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ↑ "SMLP : en route !". LTF. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- ↑ ""A SMP4 la faille a ete franchie"". LTF. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ ""SMP4: Federica creuse avec des pics de 15/19 m par jour"". LTF. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ↑ ""Antonio Tajani visite les chantiers du Lyon-Turin"". Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 4

- ↑ Design and construction

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 17

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 16

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 30

- ↑ CAPacité des RESéaux ferroviaires, Rivier, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 31

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 32

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - pp. 33–34

- ↑ Quaderno 1 - p. 35. Data are from 2007, while capacity was reduced by the 2007–10 modernization work.

- ↑ https://www.ledauphine.com/savoie/2018/09/28/lyon-turin-le-tunnel-actuel-est-pratiquement-sature-selon-reseau-ferre-de-france

- ↑ Quaderno 2 - p. 18

- ↑ Flyvbjerg, B.; Buzelius, N.; Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00946-4.

- ↑ TGV Est 11 millions de voyageurs en un an : la SNCF en avance sur ses objectifs , Simon Barthélémy L'Alsace 6 juin 2008

- ↑ https://www.ledauphine.com/savoie/2018/09/28/lyon-turin-le-tunnel-actuel-est-pratiquement-sature-selon-reseau-ferre-de-france

- ↑ Quaderno 2 - pp. 36-39

- ↑ "The base tunnel". LTF. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ↑ Povoledo, Elisabetta (17 March 2014). "Italy Divided Over Rail Line Meant to Unite". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ Tim Phillips, "Six Members of the No-TAV Movement Sentenced for Crimes During Protests, but Two Acquitted", Activist Defense, June 5, 2013.

- ↑ Commissione VIA (5 December 2010). "Progetto preliminare in variante - Chiarimenti ed integrazioni (Richiesta N° 11)" (pdf). Parte comune italo-francese. Revisione del progetto definitivo, CUP C11J05000030001 (in Italian): 21–22.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-12. Retrieved 2013-04-24. from Pro Natura Torino.

- ↑ For specific documentation in English see http://www.notavtorino.org/documenti/inglese/indice.htm

- ↑ Porta, Donatella Della; Piazza, Gianni (17 October 2007). "Local contention, global framing: The protest campaigns against the TAV in Val di Susa and the bridge on the Messina Straits". Environmental Politics. 16 (5): 864–882. doi:10.1080/09644010701634257.

References

- Quaderno 1: Linea storica - Tratta di valico [Book 1: Old line - upper section]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, May 2007

- Quaderno 2: Scenari di traffico - Arco Alpino [Book 2: Traffic scenarios - Alps passes]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, June 2007

- Quaderno 3: Linea storica - Tratta di valle [Book 3: Old line - lower section]. Osservatorio Ministeriale per il collegamento ferroviario Torino-Lione, Rome, December 2007

External links

- RFI - Rete Ferroviaria Italiana - owner of the Italian rail infrastructure

- RFF - Réseau Ferré de France - owner of the French rail infrastructure

- TELT - The company responsible for the Turin-Lyon line, owned 50% by RFI and 50% by RFF.

- http://www.notavtorino.org/documenti/inglese/indice.htm - Some documents against new railway in English

- (in Italian) TAV Turin-Lyon planned line in Google Earth/Maps