Treeshrew

| Treeshrews[1] Temporal range: ?Middle Eocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Madras treeshrew (Anathana ellioti) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Eutheria |

| Superorder: | Euarchontoglires |

| Order: | Scandentia Wagner, 1855 |

| Families | |

The treeshrews (or tree shrews or banxrings[2]) are small Euarchontoglire mammals native to the tropical forests of Southeast Asia. They make up the families Tupaiidae, the treeshrews, and Ptilocercidae, the pen-tailed treeshrew, and the entire order Scandentia. The 20 species are placed in five genera. Treeshrews have a higher brain to body mass ratio than any other mammal, including humans,[3] but high ratios are not uncommon for animals weighing less than a kilogram.

Though called 'treeshrews', and despite having previously been classified in Insectivora, they are not true shrews, and not all species live in trees. Among other things, treeshrews eat Rafflesia fruit.

Among orders of mammals, treeshrews are closely related to primates, and have been used as an alternative to primates in experimental studies of myopia, psychosocial stress, and hepatitis.[4]

Characteristics

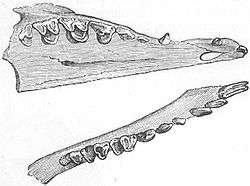

Treeshrews are slender animals with long tails and soft, greyish to reddish-brown fur. The terrestrial species tend to be larger than the arboreal forms, and to have larger claws, which they use for digging up insect prey. They are omnivorous, feeding on insects, small vertebrates, fruit, and seeds. They have poorly developed canine teeth and unspecialised molars, with an overall dental formula of: 2.1.3.33.1.3.3[5]

Treeshrews have good vision, which is binocular in the case of the more arboreal species. Most are diurnal, although the pen-tailed treeshrew is nocturnal.

Female treeshrews have a gestation period of 45 to 50 days and give birth to up to three young in nests lined with dry leaves inside tree hollows. The young are born blind and hairless, but are able to leave the nest after about a month. During this period, the mother provides relatively little maternal care, visiting her young only for a few minutes every other day to suckle them. Treeshrews reach sexual maturity after around four months, and breed for much of the year, with no clear breeding season in most species.[5]

These animals live in small family groups, which defend their territory from intruders. They mark their territories using various scent glands or urine, depending on the particular species.

The name Tupaia is derived from tupai, the Malay word for squirrel,[6] and was provided by Sir Stamford Raffles.[7]

The pen-tailed treeshrew in Malaysia is able to consume large amounts of naturally fermented nectar (with up to 3.8% alcohol content) the entire year without it having any effects on behaviour.[8]

Treeshrews have also been observed intentionally eating foods high in capsaicin, a behavior unique among mammals other than humans. A single TRPV1 mutation reduces their pain response to capsaicinoids, which scientists believe is an evolutionary adaptation to be able to consume spicy foods in their natural habitats.[9]

Classification

Treeshrews were moved from Insectivora to the Primates order because of certain internal similarities to the latter (for example, similarities in the brain anatomy, highlighted by Sir Wilfred Le Gros Clark), and classified as a "primitive prosimian". However, molecular phylogenetic studies suggested the treeshrews should be given the same rank (order) as the primates and, with the primates and the flying lemurs (colugos), belong to the clade Euarchonta. According to this classification, the Euarchonta are sister to the Glires (lagomorphs and rodents), and the two groups are combined into the clade Euarchontoglires.[10] Other arrangements of these orders were proposed in the past.[11] Although it is known that Scandentia is one of the most basal Euarchontoglire clades, the exact phylogenetic position is not yet considered resolved, and it may be a sister of Glires, Primatomorpha or Dermoptera or to all other Euarchontoglires.[12][13] Recent studies place Scandentia as sister of the Glires, invalidating Euarchonta:[14][15]

| Euarchontoglires |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, the alternative placement of treeshrews as sister to both Glires and Primatomorpha cannot be ruled out.[15]

- ORDER SCANDENTIA

- Family Tupaiidae

- Genus Anathana

- Madras treeshrew, A. ellioti

- Genus Dendrogale

- Bornean smooth-tailed treeshrew, D. melanura

- Northern smooth-tailed treeshrew, D. murina

- Genus Tupaia

- Northern treeshrew, T. belangeri

- Golden-bellied treeshrew, T. chrysogaster

- Striped treeshrew, T. dorsalis

- Common treeshrew, T. glis

- Slender treeshrew, T. gracilis

- Horsfield's treeshrew, T. javanica

- Long-footed treeshrew, T. longipes

- Pygmy treeshrew, T. minor

- Calamian treeshrew, T. moellendorffi

- Mountain treeshrew, T. montana

- Nicobar treeshrew, T. nicobarica

- Palawan treeshrew, T. palawanensis

- Painted treeshrew, T. picta

- Ruddy treeshrew, T. splendidula

- Large treeshrew, T. tana

- Genus Urogale

- Mindanao treeshrew, U. everetti

- Genus Anathana

- Family Ptilocercidae

- Genus Ptilocercus

- Pen-tailed treeshrew, P. lowii

- Genus Ptilocercus

- Family Tupaiidae

Fossil record

The fossil record of treeshrews is poor. The oldest putative treeshrew, Eodendrogale parva, is from the Middle Eocene of Henan, China, but the identity of this animal is uncertain. Other fossils have come from the Miocene of Thailand, Pakistan, India, and Yunnan, China, as well as the Pliocene of India. Most belong to the family Tupaiidae, but some still-undescribed fossils from Yunnan are thought to be closer to the pen-tailed treeshrew. Named fossil species include Prodendrogale yunnanica, Prodendrogale engesseri, and Tupaia storchi from Yunnan, Tupaia miocenica from Thailand, and Palaeotupaia sivalicus from India.[16]

References

- ↑ Helgen, K.M. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 104–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑

- ↑ http://genome.wustl.edu/genomes/view/tupaia_belangeri is an article on Tupaia belangeri from The Genome Institute published by Washington University, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20100601201841/https://www.genome.wustl.edu/genomes/view/tupaia_belangeri

- ↑ Cao, J; Yang, E.B.; Su, J-J; Li, Y; Chow, P (2003). "The tree shrews: Adjuncts and alternatives to primates as models for biomedical research" (PDF). Journal of Medical Primatology. 32: 123–130. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - 1 2 Martin, Robert D. (1984). Macdonald, D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. pp. 440–445. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 245. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- ↑ Craig, John (1849). A new universal etymological technological, and pronouncing dictionary of the English Language.

- ↑ Moscowicz, Clara (2008). "Tiny tree shrew can drink you under the table".

- ↑ "See Why Tree Shrews Are Only the Second Known Mammal to Seek Spicy Food". relay.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ↑ Janecka, Jan E.; Miller, Webb; Pringle, Thomas H.; Wiens, Frank; Zitzmann, Annette; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Springer, Mark S.; Murphy, William J. (2 November 2007). "Molecular and genomic data identify the closest living relatives of the Primates" (PDF). Science. 318 (5851): 792–794. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..792J. doi:10.1126/science.1147555. PMID 17975064.

- ↑ Pettigrew JD, Jamieson BG, Robson SK, Hall LS, McAnally KI, Cooper HM (1989). "Phylogenetic relations between microbats, megabats, and primates" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Mammalia: Chiroptera and Primates. 325 (1229): 489–559. Bibcode:1989RSPTB.325..489P. doi:10.1098/rstb.1989.0102.

- ↑ Foley, Nicole M.; Springer, Mark S.; Teeling, Emma C. (19 July 2016). "Mammal madness: Is the mammal tree of life not yet resolved?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 371 (1699): 20150140. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0140. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4920340. PMID 27325836.

- ↑ Kumar, Vikas; Hallström, Björn M.; Janke, Axel (1 April 2013). "Coalescent-based genome analyses resolve the early branches of the Euarchontoglires". PLoS One. 8 (4): e60019. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860019K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060019. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3613385. PMID 23560065.

- ↑ Meredith, Robert W.; Janečka, Jan E.; Gatesy, John; Ryder, Oliver A.; Fisher, Colleen A.; Teeling, Emma C.; Goodbla, Alisha; Eizirik, Eduardo; Simão, Taiz L. L. (28 October 2011). "Impacts of the Cretaceous terrestrial revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification". Science. 334 (6055): 521–524. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..521M. doi:10.1126/science.1211028. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21940861.

- 1 2 Zhou, Xuming; Sun, Fengming; Xu, Shixia; Yang, Guang; Li, Ming (1 March 2015). "The position of tree shrews in the mammalian tree: Comparing multi-gene analyses with phylogenomic results leaves monophyly of Euarchonta doubtful". Integrative Zoology. 10 (2): 186–198. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12116. ISSN 1749-4877.

- ↑ Ni, X.; Qiu, Z. (2012). "Tupaiine tree shrews (Scandentia, Mammalia) from the Yuanmou Lufengpithecus locality of Yunnan, China". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 131: 51–60. doi:10.1007/s13358-011-0029-0.