Tree of life

The tree of life is a widespread myth (mytheme) or archetype in the world's mythologies, related to the concept of sacred tree more generally,[1] and hence in religious and philosophical tradition.

The expression tree of life was used as a metaphor for the phylogenetic tree of common descent in the evolutionary sense in a famous passage by Charles Darwin (1872).[2]

The tree of knowledge, connecting to heaven and the underworld, and the tree of life, connecting all forms of creation, are both forms of the world tree or cosmic tree,[3] and are portrayed in various religions and philosophies as the same tree.[4]

Religion and mythology

Various trees of life are recounted in folklore, culture and fiction, often relating to immortality or fertility. They had their origin in religious symbolism.

Ancient Iran

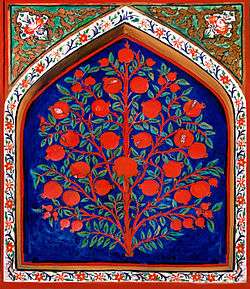

In the Avestan literature and Iranian mythology, there are several sacred vegetal icons related to life, eternality and cure, like: Amesha Spenta Amordad (guardian of plants, goddess of trees and immortality), Gaokerena (or white Haoma, a tree that its vivacity would certify continuance of life in universe), Bas tokhmak (a tree with remedial attribute, retentive of all herbal seeds, and destroyer of sorrow), Mashyа and Mashyane (parents of the human race in Iranian myths), Barsom (copped offshoots of pomegranate, gaz or Haoma that Zoroastrians use in their rituals), Haoma (a plant, unknown today, that was source of sacred potable), etc.[5]

Gaokerena is a large, sacred Haoma planted by Ahura Mazda. Ahriman (Ahreman, Angremainyu) created a frog to invade the tree and destroy it, aiming to prevent all trees from growing on the earth. As a reaction, Ahura Mazda created two kar fish staring at the frog to guard the tree. The two fish are always staring at the frog and stay ready to react to it. Because Ahriman is responsible for all evil including death, while Ahura Mazda is responsible for all good (including life).

haoma is another sacred plant due to the drink made from it. The preparation of the drink from the plant by pounding and the drinking of it are central features of Zoroastrian ritual. Haoma is also personified as a divinity. It bestows essential vital qualities—health, fertility, husbands for maidens, even immortality. The source of the earthly haoma plant is a shining white tree that grows on a paradisiacal mountain. Sprigs of this white haoma were brought to earth by divine birds.

Haoma is the Avestan form of the Sanskrit soma. The near identity of the two in ritual significance is considered by scholars to point to a salient feature of an Indo-Iranian religion antedating Zoroastrianism.[6][7]

Another related issue in ancient mythology of Iran is the myth of Mashyа and Mashyane, two trees who were the ancestors of all living beings. This myth can be considered as a prototype for the creation myth where living beings are created by Gods (who have a human form).

Ancient Mesopotamia and Urartu

The Assyrian tree of life was represented by a series of nodes and criss-crossing lines. It was apparently an important religious symbol, often attended to in Assyrian palace reliefs by human or eagle-headed winged genies, or the King, and blessed or fertilized with bucket and cone. Assyriologists have not reached consensus as to the meaning of this symbol. The name "Tree of Life" has been attributed to it by modern scholarship; it is not used in the Assyrian sources. In fact, no textual evidence pertaining to the symbol is known to exist.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a similar quest for immortality. In Mesopotamian mythology, Etana searches for a 'plant of birth' to provide him with a son. This has a solid provenance of antiquity, being found in cylinder seals from Akkad (2390–2249 BCE).

In ancient Urartu, the tree of life was a religious symbol and was drawn on walls of fortresses and carved on the armor of warriors. The branches of the tree were equally divided on the right and left sides of the stem, with each branch having one leaf, and one leaf on the apex of the tree. Servants stood on each side of the tree with one of their hands up as if they are taking care of the tree.

Baha'i Faith

The concept of the tree of life appears in the writings of the Bahá'í Faith, where it can refer to the Manifestation of God, a great teacher who appears to humanity from age to age. An example of this can be found in the Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh:[8][9]

"Have ye forgotten that true and radiant morn, when in those hallowed and blessed surroundings ye were all gathered in My presence beneath the shade of the tree of life, which is planted in the all-glorious paradise? Awestruck ye listened as I gave utterance to these three most holy words: O friends! Prefer not your will to Mine, never desire that which I have not desired for you, and approach Me not with lifeless hearts, defiled with worldly desires and cravings. Would ye but sanctify your souls, ye would at this present hour recall that place and those surroundings, and the truth of My utterance should be made evident unto all of you."

Also, in the Tablet of Ahmad of Bahá'u'lláh: "Verily He is the Tree of Life, that bringeth forth the fruits of God, the Exalted, the Powerful, the Great".[10]

Bahá'u'lláh refers to his male descendants as branches (Arabic: ﺍﻏﺼﺎﻥ ʾaghṣān) [11] and calls women leaves.[12]

A distinction has been made between the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The latter represents the physical world with its opposites, such as good and evil and light and dark. In a different context from the one above, the tree of life represents the spiritual realm, where this duality does not exist.[13]

Buddhism

The Bo tree, also called Bodhi tree, according to Buddhist tradition, is the pipal (Ficus religiosa) under which the Buddha sat when he attained Enlightenment (Bodhi) at Bodh Gaya (near Gaya, west-central Bihar state, India). A living pipal at Anuradhapura, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), is said to have grown from a cutting from the Bo tree sent to that city by King Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE.[14]

According to Tibetan tradition when Buddha went to the holy Lake Manasorovar along with 500 monks, he took with him the energy of Prayaga Raj. Upon his arrival, he installed the energy of Prayaga Raj near Lake Manasorovar, at a place now known as Prayang. Then he planted the seed of this eternal banyan tree next to Mt. Kailash on a mountain known as the "Palace of Medicine Buddha".[15]

China

In Chinese mythology, a carving of a tree of life depicts a phoenix and a dragon; the dragon often represents immortality. A Taoist story tells of a tree that produces a peach of immortality every three thousand years, and anyone who eats the fruit receives immortality.

An archaeological discovery in the 1990s was of a sacrificial pit at Sanxingdui in Sichuan, China. Dating from about 1200 BCE, it contained three bronze trees, one of them 4 meters high. At the base was a dragon, and fruit hanging from the lower branches. At the top is a bird-like (Phoenix) creature with claws. Also found in Sichuan, from the late Han dynasty (c 25 – 220 CE), is another tree of life. The ceramic base is guarded by a horned beast with wings. The leaves of the tree represent coins and people. At the apex is a bird with coins and the Sun.

Christianity

The tree of life first appears in Genesis 2:9 and 3:22-24 as the source of eternal life in the Garden of Eden, from which access is revoked when man is driven from the garden. It then reappears in the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, and most predominantly in the last chapter of that book (Chapter 22) as a part of the new garden of paradise. Access is then no longer forbidden, for those who "wash their robes" (or as the textual variant in the King James Version has it, "they that do his commandments") "have right to the tree of life" (v.14). A similar statement appears in Rev 2:7, where the tree of life is promised as a reward to those who overcome. Revelation 22 begins with a reference to the "pure river of water of life" which proceeds "out of the throne of God". The river seems to feed two trees of life, one "on either side of the river" which "bear twelve manner of fruits" "and the leaves of the tree were for healing of the nations" (v.1-2).[16] Or this may indicate that the tree of life is a vine that grows on both sides of the river, as John 15:1 would hint at.

Pope Benedict XVI has said that "the Cross is the true tree of life."[17] Saint Bonaventure taught that the medicinal fruit of the tree of life is Christ himself.[18] Saint Albert the Great taught that the Eucharist, the Body and Blood of Christ, is the Fruit of the Tree of Life.[19] Augustine of Hippo said that the tree of life is Christ:

All these things stood for something other than what they were, but all the same they were themselves bodily realities. And when the narrator mentioned them he was not employing figurative language, but giving an explicit account of things which had a forward reference that was figurative. So then the tree of life also was Christ... and indeed God did not wish the man to live in Paradise without the mysteries of spiritual things being presented to him in bodily form. So then in the other trees he was provided with nourishment, in this one with a sacrament... He is rightly called whatever came before him in order to signify him.[20]

In Eastern Christianity the tree of life is the love of God.[21]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The tree of life vision is a vision described and discussed in the Book of Mormon. According to the Book of Mormon, the vision was received in a dream by the prophet Lehi, and later in vision by his son Nephi, who wrote about it in the First Book of Nephi. The vision includes a path leading to a tree symbolizing salvation, with an iron rod along the path whereby followers of Jesus may hold to the rod and avoid wandering off the path into pits or waters symbolizing the ways of sin. The vision also includes a large building wherein the wicked look down at the righteous and mock them.

The vision is said to symbolize the spiritual plight of humanity and is a well known and cited story within Mormonism. A Mormon commentator reflected a common Mormon belief that the vision is "one of the richest, most flexible, and far-reaching pieces of symbolic prophecy contained in the standard works [scriptures]."[22]

Europe

In Dictionnaire Mytho-Hermetique (Paris, 1737), Antoine-Joseph Pernety, a famous alchemist, identified the tree of life with the Elixir of life and the Philosopher's Stone.

In Eden in the East (1998), Stephen Oppenheimer suggests that a tree-worshipping culture arose in Indonesia and was diffused by the so-called "Younger Dryas" event of c. 10,900 BCE or 12,900 BP, after which the sea level rose. This culture reached China (Szechuan), then India and the Middle East. Finally the Finno-Ugaritic strand of this diffusion spread through Russia to Finland where the Norse myth of Yggdrasil took root.

Georgia

The Borjgali (Georgian: ბორჯღალი) is an ancient Georgian tree of life symbol.

Germanic paganism and Norse mythology

In Germanic paganism, trees played (and, in the form of reconstructive Heathenry and Germanic Neopaganism, continue to play) a prominent role, appearing in various aspects of surviving texts and possibly in the name of gods.

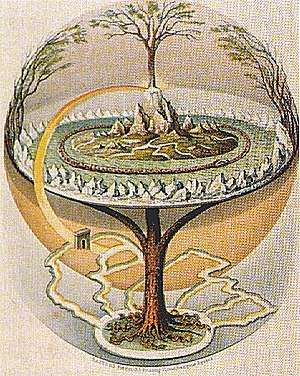

The tree of life appears in Norse religion as Yggdrasil, the world tree, a massive tree (sometimes considered a yew or ash tree) with extensive lore surrounding it. Perhaps related to Yggdrasil, accounts have survived of Germanic Tribes' honouring sacred trees within their societies. Examples include Thor's Oak, sacred groves, the Sacred tree at Uppsala, and the wooden Irminsul pillar. In Norse Mythology, the apples from Iðunn's ash box provide immortality for the gods.

Islam

The "Tree of Immortality" (Arabic: شجرة الخلود) is the tree of life motif as it appears in the Quran. It is also alluded to in hadiths and tafsir. Unlike the biblical account, the Quran mentions only one tree in Eden, also called the tree of immortality, which Allah specifically forbade to Adam and Eve.[23][24] Satan, disguised as a serpent, repeatedly told Adam to eat from the tree, and eventually both Adam and Eve did so, thus disobeying Allah.[25] The hadiths also speak about other trees in heaven.[26]

Ahmadiyya

According to the Indian Ahmadiyya movement founded in 1889, Quranic reference to the tree is symbolic; eating of the forbidden tree signifies that Adam disobeyed God.[27][28]

Jewish sources

Etz Chaim, Hebrew for "tree of life," is a common term used in Judaism. The expression, found in the Book of Proverbs, is figuratively applied to the Torah itself. Etz Chaim is also a common name for yeshivas and synagogues as well as for works of Rabbinic literature. It is also used to describe each of the wooden poles to which the parchment of a Sefer Torah is attached.

The tree of life is mentioned in the Book of Genesis; it is distinct from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. After Adam and Eve disobeyed God by eating fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, they were driven out of the Garden of Eden. Remaining in the garden, however, was the tree of life. To prevent their access to this tree in the future, Cherubim with a flaming sword were placed at the east of the garden. (Genesis 3:22-24)

In the Book of Proverbs, the tree of life is associated with wisdom: "[Wisdom] is a tree of life to them that lay hold upon her, and happy [is every one] that retaineth her." (Proverbs 3:13-18) In 15:4 the tree of life is associated with calmness: "A soothing tongue is a tree of life; but perverseness therein is a wound to the spirit."[29]

The Book of Enoch, generally considered non-canonical, states that in the time of the great judgment God will give all those whose names are in the Book of Life fruit to eat from the tree of life.

Kabbalah

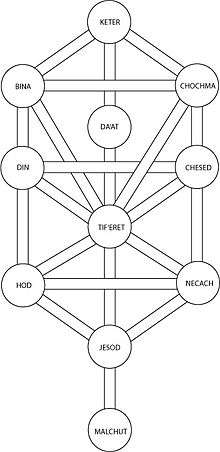

Jewish mysticism depicts the tree of life in the form of ten interconnected nodes, as the central symbol of the Kabbalah. It comprises the ten Sefirot powers in the divine realm. The panentheistic and anthropomorphic emphasis of this emanationist theology interpreted the Torah, Jewish observance, and the purpose of Creation as the symbolic esoteric drama of unification in the Sefirot, restoring harmony to Creation. From the time of the Renaissance onwards, Jewish Kabbalah became incorporated as an important tradition in non-Jewish Western culture, first through its adoption by Christian Kabbalah, and continuing in Western esotericism occult Hermetic Qabalah. These adapted the Judaic Kabbalah tree of life syncretically by associating it with other religious traditions, esoteric theologies, and magical practices.

Mesoamerica

The concept of world trees is a prevalent motif in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cosmologies and iconography. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.[30]

Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and mythological traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as or represented by a ceiba tree, and is known variously as a wacah chan or yax imix che, depending on the Mayan language.[31] The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree's spiny trunk.[30]

Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer codices.[30] It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a "water-monster," symbolic of the underworld). The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.[32]

North America

In a myth passed down among the Iroquois, The World on the Turtle's Back, explains the origin of the land in which a tree of life is described. According to the myth, it is found in the heavens, where the first humans lived, until a pregnant woman fell and landed in an endless sea. Saved by a giant turtle from drowning, she formed the world on its back by planting bark taken from the tree.

The tree of life motif is present in the traditional Ojibway cosmology and traditions. It is sometimes described as Grandmother Cedar, or Nookomis Giizhig in Anishinaabemowin.

In the book Black Elk Speaks, Black Elk, an Oglala Lakota (Sioux) wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man), describes his vision in which after dancing around a dying tree that has never bloomed he is transported to the other world (spirit world) where he meets wise elders, 12 men and 12 women. The elders tell Black Elk that they will bring him to meet "Our Father, the two-legged chief" and bring him to the center of a hoop where he sees the tree in full leaf and bloom and the "chief" standing against the tree. Coming out of his trance he hopes to see that the earthly tree has bloomed, but it is dead.[33]

Serer religion

In Serer religion, the tree of life as a religious concept forms the basis of Serer cosmogony. Trees were the first things created on Earth by the supreme being Roog (or Koox among the Cangin). In the competing versions of the Serer creation myth, the Somb (Prosopis africana) and the Saas tree (acacia albida) are both viewed as trees of life.[34] However, the prevailing view is that, the Somb was the first tree on Earth and the progenitor of plant life.[34][35] The Somb was also used in the Serer tumuli and burial chambers, many of which had survived for more than a thousand years.[34] Thus, Somb is not only the tree of life in Serer society, but the symbol of immortality.[34]

Turkic

The World Tree or tree of life is a central symbol in Turkic mythology. It is a common motif in carpets. In 2009 it was introduced as the main design of the common Turkish lira sub-unit 5 kuruş.

Hinduism

In the sacred books of Hinduism (Sanatana Dharma), Puranas mention divine tree Kalpavruksham (కల్పవృక్షం, कल्पवृक्ष ). This divine tree is guarded by Gandharvas in the garden of Amaravati, city under the control of Indra, King of gods. Popular story goes like this, for a very long time, gods and demi-gods who are believed to be fathered by Kashyapa Prajapati and have different mothers. After a long time frequent battles between the two half-brother clans, both groups decided to churn the milky ocean to obtain Amrutam (అమృతం, अमृत ) and share equally. During the churning, along with many other mythical items emerged the Kalpavruksham (కల్పవృక్షం, कल्पवृक्ष ). It is gold in colour. It has mesmerizing aura. It can be pleased with chanting and offers. When it is pleased, it grants every wish.

Popular culture

Austrian symbolist artist Gustav Klimt portrayed his version of the tree of life in his painting, The Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze. This iconic painting later inspired the external facade of the "New Residence Hall" (also called the "Tree House"), a colorful 21-story student residence hall at Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston, Massachusetts.[36]

In George Herbert's poem The Sacrifice (part of The Temple, 1633), the tree of life is the rood on which Jesus Christ was crucified. In C. S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia, the tree of life plays a role, especially in the sixth published book (the first in the in-world chronology) The Magician's Nephew.

Alex Proyas' 2009 film Knowing ends with the two young protagonists directed towards the tree of life.[37]

In season 13 of the TV series Supernatural, fruit from the tree of life is an important ingredient in a spell to open a portal to an alternate reality. The angel Castiel is able to find the tree in Syria and returns from a mission with the fruit in Scoobynatural. The fruit is used in subsequent episodes as part of the spell to open the portal between the worlds.

Physical "trees of life"

- The Arborvitae gets its name from the Latin for "tree of life."

- The Tule tree of Aztec mythology is also associated with a real tree. This Tule tree can be found in Oaxaca, Mexico.

- There is a Tree of Life in Bahrain.

- Metaphor: The Tree of Utah is an 87-foot (27 m) high sculpture in the Utah Bonneville Salt Flats that is also known as the "Tree of Life".

- In some parts of the Caribbean and in the Philippines, the coconut is considered the "tree of life" as its parts can easily be used for short/medium term survival such as for food, shelter, and various implements.

- Disney's Animal Kingdom theme park features an artificial tree dubbed "The Tree of Life", which has about 325 carvings of different species of animals. Inside the tree is the It's Tough to Be a Bug! attraction.

- The West African Moringa oleifera tree is regarded as a "tree of life" or "miracle tree" by some because it is arguably the most nutritious source of plant-derived food discovered on the planet.[38] Modern scientists and some missionary groups have considered the plant as a possible solution for the treatment of severe malnutrition[39] and aid for those with HIV/AIDS.[40]

See also

References

- ↑ Giovino, Mariana (2007). The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History of Interpretations, page 129. Saint-Paul. ISBN 9783727816024

- ↑ "As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications." Darwin, The Origin of Species (1872), 104f.

- ↑ World tree in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Tryggve N. D. Mettinger (2007). The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2–3. Eisenbrauns. p. 5. ISBN 978-1575061412. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Taheri, Sadreddin (2013). "Plant of life, in Ancient Iran, Mesopotamia & Egypt". Tehran: Honarhay-e Ziba Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 15.

- ↑ "haoma (Zoroastrianism) - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ "HAOMA i. BOTANY – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑

- Taherzadeh, Adib (1976). The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, Volume 1: Baghdad 1853-63. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 80. ISBN 0-85398-270-8.

- ↑ Kazemi, Farshid (2009). Mysteries of Alast: The Realm of Subtle Entities and the Primordial Covenant in the Babi-Bahá'í Writings. Bahá'í Studies Review 15.

- ↑ "Tablet of Ahmad". www.bahaiprayers.org.

- ↑ Smith, Peter (2000). "Aghsán". A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 30. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ↑ Liya, Sally (2004). The Use of Trees as Symbols in the World Religions in: Solas, 4. Donegal, Ireland. Association for Baha'i Studies English-Speaking Europe. P. 55.

- ↑ Abdu'l-Baha, Some Answered Questions, p. 122.

- ↑ "Bo tree (tree) - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ "The Kumbha Mela Times". Kmt.himalayaninstitute.org. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ The Bible (King James version), The Revelation of St. John, chapter & verses as noted.

- ↑ Gheddo, Piero (March 20, 2005). "Pope tells WYD youth: the Cross of Jesus is the real tree of life". AsiaNews.it. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- ↑ "The Tree of Life". Yale University. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- ↑ "The Eucharist as the Fruit of the Tree of Life | Saint Albert the Great". CrossroadsInitiative.com. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- ↑ Augustine, The Literal Meaning of Genesis, VIII, 4, 8 (On Genesis, New City Press, p. 351-353)

- ↑ Saint Isaac the Syrian says that "Paradise is the love of God, in which the bliss of all the beatitudes is contained," and that "the tree of life is the love of God" (Homily 72).

- ↑ Corbin T. Volluz, "Lehi's Dream of the Tree of Life: Springboard to Prophecy," JBMS 2/2 (1993): 38. - as quoted in Lehi's Vision of the Tree of Life: Understanding the Dream as Visionary Literature, Charles Swift, Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute, 2005. P. 52–63 - online version at

- ↑ Wheeler, Brannon (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis (annotated ed.). Continuum. p. 24. ISBN 978-0826449566.

Abu Hurayrah: The Prophet Muhammad said: "In Paradise is a tree in the shade of which the stars course 100 years without cutting it: the Tree of Immortality.

- ↑ Oliver Leaman, ed. (2006). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 11. ISBN 9780415326391.

Unlike the biblical account of Eden, the Qur'an mentions only one special tree in Eden, the Tree of Immortality, from which Adam and Eve were prohibited.

- ↑ Three Translations of the Koran (Al-Qur'an) Side by Side Quran 20:120, "Shall I show thee the tree of immortality and power that wasteth not away? S: But the Shaitan made an evil suggestion to him; he said: O Adam! Shall I guide you to the tree of immortality and a kingdom which decays not? "

- ↑ Maulana Muhammad Ali (2011) Introduction to the Study of the Holy Qur'an "This in itself gives an indication that it is the well-known tree of evil, for both good and evil are compared to two trees in 14:24–25 and elsewhere. This is further corroborated by the devil's description of it as “the tree of immortality” (20:120), ..."

- ↑ Bilal Khalid. "Quran, Adam and Original Sin". Al Islam. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ The Holy Quran with English Translation and Commentary Volume 1. Islam International Publications. p. 86. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ For other direct references to the tree of life in the Jewish biblical canon, see also Proverbs 11:30, 13:12.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05068-2.

- ↑ Finley, Michael (2003). "Raising the sky: The Maya creation myth and the Milky Way". The Real Maya Prophecies: Astronomy in the Inscriptions and Codices. Maya Astronomy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ↑ Freidel, David A.; Linda Schele; Joy Parker (1993). Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0-688-10081-0.

- ↑ "Black Elk Speaks". Visions of the Other World. First People of America and Canada - Turtle Island. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 (in French) Gravrand, Henry, "La Civilisation Sereer - Pangool", vol. 2., Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal (1990), pp 125–6, 199–200, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ↑ (in French) & (in English) Niangoran-Bouah, Georges, "L'univers Akan des poids à peser l'or : les poids dans la société", Les nouvelles éditions africaines - MLB, (1987), p 25, ISBN 2723614034

- ↑ "MassArt Residence Story: This is the house that collaboration built". MASCO: Medical Academic and Scientific Community Organization. MASCO, Inc. Retrieved 2013-12-24.

- ↑ Albertson, Cammila (2009). "Knowing: Review". TV Guide. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ "Moringa". Leafforlife.org. 2002-06-03. Retrieved 2011-12-25.

- ↑ Weekend Edition Saturday (2000-08-12). "Moringa Oleifera : Malnutrition Fighter". NPR. Retrieved 2011-12-25.

- ↑ Burger DJ; Fuglie L; Herzig JW (12 July 2002). "The possible role of Moringa oleifera in HIV/AIDS supportive treatment". Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

Further reading

- Marsella, Elena Maria (1966). The Quest for Eden. New York: Philosophical Library. ISBN 0802210635.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tree of life. |

- tolweb.org – Tree of Life Web Project at tolweb.org

- OneZoom Tree of Life Explorer at onezoom.org

- Trees For Life at treesforlife.org

- Moringa at demoringa.com - Encyclopedia illustrated in Spanish on the Moringa

- The Ilanot Project. Haifa Uni.