Sanxingdui

| 三星堆 | |

.jpg) Sanxingdui bronze heads with gold foil masks | |

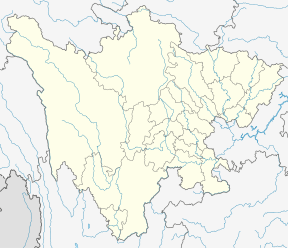

Location within Sichuan | |

| Location | Guanghan |

|---|---|

| Region | Sichuan |

| Coordinates | 30°59′35″N 104°12′00″E / 30.993°N 104.200°E |

| History | |

| Cultures |

Baodun Sanxingdui |

Sanxingdui (Chinese: 三星堆; pinyin: Sānxīngduī; literally: "three stars mound") is the name of an archaeological site and a major Bronze Age culture in modern Guanghan, Sichuan, China. Largely discovered in 1986, following a preliminary finding in 1929,[1] archaeologists excavated remarkable artifacts that radiocarbon dating placed in the 12th-11th centuries BCE.[2] The type site for the Sanxingdui culture that produced these artifacts, archeologists have identified the locale with the ancient kingdom of Shu. The artifacts are displayed in the Sanxingdui Museum located near the city of Guanghan.[2]

The discovery at Sanxingdui, as well as other discoveries such as the Xingan tombs in Jiangxi, challenges the traditional narrative of Chinese civilization spreading from the central plain of the Yellow River, and Chinese archaeologists have begun to speak of "multiple centers of innovation jointly ancestral to Chinese civilization."[3][4]

Sanxingdui, along with the Jinsha site and the Tombs of boat-shaped coffins, is on UNESCO's list of tentative world heritage sites.[5]

Background

.jpg)

Many Chinese archaeologists have identified the Sanxingdui culture to be part of the ancient kingdom of Shu, linking the artifacts found at the site to its early legendary kings. References to a Shu kingdom that can be reliably dated to such an early period in Chinese historical records are scant (it is mentioned in Shiji and Shujing as an ally of the Zhou who defeated the Shang), but accounts of the legendary kings of Shu may be found in local annals.[7]

According to the Chronicles of Huayang compiled in the Jin Dynasty (265–420), the Shu kingdom was founded by Cancong (蠶叢).[8] Cancong was described as having protruding eyes, a feature that is found in the figures of Sanxingdui. Other eye-shaped objects were also found which might suggest worship of the eyes. Other rulers mentioned in Chronicles of Huayang include Boguan (柏灌), Yufu (魚鳧), and Duyu (杜宇). Many of the objects are fish and bird-shaped, and these have been suggested to be totems of Boguan and Yufu (the name Yufu actually means fish cormorant), and the clan of Yufu has been suggested as the one most likely to be associated with Sanxingdui.[9]

Discoveries have also since been made at Jinsha, which is located 40 km away and has close link with the Sanxingdui Culture. It is thought to be the relocated capital of the Shu Kingdom.[10] It has also been suggested that the Jinsha site may be the hub and capital of Duyu clan.[11]

Archaeological site

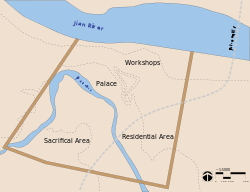

The Sanxingdui archaeological site is located about 4 km northeast of Nanxing Township, Guanghan, Deyang, Sichuan Province. Archaeological digs at the site showed evidence of a walled city founded c. 1,600 BCE. The trapezoidal city has an east wall 2,000 m, south wall 2,000 m, west wall 1,600 m enclosing 3.6 km2,[12] similar in scale to the inner city of the Zhengzhou Shang City.

The city was built on the banks of the Yazi River (Chinese: 涧河; pinyin: Jiān Hé), and enclosed part of its tributary, Mamu River, within the city walls. The city walls were 40 m at the base and 20 m at the top and varied in height from 8–10 m. There was a smaller set of inner walls.

The walls were surrounded by canals 25–20 m wide and 2–3 m deep. These canals were used for irrigation, inland navigation, defense, and flood control. The city was divided into residential, industrial and religious districts organized around a dominant central axis. It is along this axis that most of the pit burial have been found on four terraces. The structures were timber framed adobe rectangular halls. The largest was a meeting hall about 200 m2.

Discovery

Evidence of an ancient culture in this region was first found in 1929 when a farmer unearthed a large stash of jade relics while digging a well, many of which then found their way through the years into the hands of private collectors. Generations of Chinese archaeologists searched the area without success until 1986, when workers accidentally found sacrificial pits containing thousands of gold, bronze, jade, and pottery artifacts that had been broken (perhaps ritually disfigured), burned, and carefully buried. The first sacrificial pit was found on the site of the Lanxing Second Brick Factory on July 18, 1986. The second sacrificial pit was found a little less than a month later on August 14, 1986, only 20–30 meters from the first one.

Bronze objects found in the second sacrificial pit included male sculptures, animal-faced sculptures, bells, decorative animals such as dragons, snakes, chicks, and birds, and axes. Tables, masks and belts were some of the objects found made out of gold while objects made out of jade included axes, tablets, rings, knives and tubes. There was also a large amount of ivory and clamshells. Researchers were astonished to find an artistic style that was completely unknown in the history of Chinese art, whose baseline had been the history and artifacts of the Yellow River civilization(s).

.jpg)

All the Sanxingdui discoveries aroused scholarly interest, but the bronzes were what excited the world. Task Rosen of the British Museum considered them to be more outstanding than the Terracotta Army in Xi'an. The first exhibits of Sanxingdui bronzes were held in Beijing (1987, 1990) and the Olympic Museum in Lausanne (1993). Sanxingdui exhibits traveled worldwide, and tickets were sold out everywhere; from the Hybary Arts Museum in Munich (1995), the Swiss National Museum in Zurich (1996), the British Museum in London (1996), the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen (1997), the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (1998), several museums in Japan (1998), the National Palace Museum in Taipei (1999), to the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore (2007).

Nevertheless, despite the interest in the excavated finds, the site itself suffered from flooding and pollution, and was for this reason included in the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund.[15] For the preservation of the site, funding was offered by American Express to construct a protective dike. Also, in 1997, the Sanxingdui Museum opened near the original site.

Sanxingdui Culture

| Geographical range | Chengdu Plain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age China | ||||||

| Dates | c. 1700 – c. 1150 BCE[16] | ||||||

| Type site | Sanxingdui | ||||||

| Preceded by | Baodun culture | ||||||

| Followed by | Shi'erqiao | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 三星堆文化 | ||||||

| |||||||

The culture of the Sanxingdui site is thought to be divided into several phases. The Sanxingdui Culture which corresponds to periods II-III of the site, was a mysterious civilization in southern China.[17] This culture is contemporaneous with the Shang Dynasty, however they developed a different method of bronze-making from the Shang. The first phase which corresponds to period I of the site belongs to the Baodun, and the final phase (period IV) the culture merged with Ba and Chu cultures. The Sanxingdui culture ended, possibly either as a result of natural disasters (evidence of massive flooding were found), or invasion by a different culture.[17]

The culture was a strong central theocracy with trade links to bronze from Yin and ivory from Southeast Asia.[18] Such evidence of independent cultures in different regions of China defies the traditional theory that the Yellow River was the sole "cradle of Chinese civilization."[18]

Metallurgy

This ancient culture had a well developed bronze casting culture which permitted the manufacture of many impressive articles, for instance, the world's oldest life-size standing human statue (260 cm high, 180 kg), and a bronze tree with birds, flowers, and ornaments (396 cm), which some have identified as renderings of the fusang tree of Chinese mythology.

The most striking finds were dozens of large bronze masks and heads (at least six with gold foil masks originally attached) represented with angular human features, exaggerated almond-shaped eyes, some with protruding pupils, and large upper ears. Many Sanxingdui bronze faces had traces of paint smears: black on the disproportionately large eyes and eyebrows, and vermillion on the lips, nostrils, and ear holes.[19] Vermillion is interpreted "not be coloring but something ritually offered for the head to taste, smell, and hear (or something that gave it the power to breathe, hear, and speak)." Based upon the design of these heads, archeologists believe they were mounted on wooden supports or totems, perhaps dressed in clothing.[20] Liu Yang concludes "masked ritual played a vital role in community life of the ancient Sanxingdui inhabitants", and characterizes these bronze ritual masks as something that may have worn by a shi (尸; "corpse") "personator, impersonator; ceremonial representative of a dead relative".[21]

The shi was generally a close, young relative who wore a costume (possibly including a mask) reproducing the features of the dead person. The shi was an impersonator, that is, a person serving as a reminder of the ancestor to whom sacrifice was being offered. During such a ceremony, the impersonator was much more than an actor in a drama. Although the exact meaning may have been different, the group of Sanxingdui masked figures in bronze all have the character of an impersonator. It is likely the masks were used to impersonate and identify with certain supernatural beings in order to effect some communal good.[20]

Another scholar [22] compares these "bulging-eyed, big-eared bronze heads and masks" with "eye-idols" (effigies with large eyes and open mouths designed to induce hallucinations) in Julian Jaynes's bicameral hypothesis; and [23] proposes, "It is possible that southern Chinese personators wore these hypnotic bronze masks, recursively representing the spirit of a dead ancestor with a mask that represents a face disguised by a mask."

Other bronze artifacts include birds with eagle-like bills, tigers, a large snake, zoomorphic masks, bells, and what appears to be a bronze spoked wheel but is more likely to be decoration from an ancient shield. Apart from bronze, Sanxingdui finds included jade artifacts consistent with earlier Chinese neolithic cultures, such as cong and zhang.

Cosmology

As far back as Neolithic times, the Chinese identified the four quadrants of the sky with animals: Azure Dragon of the East, Vermillion Bird of the South, White Tiger of the West, and Black Tortoise of the North. Each of these Four Symbols (Chinese constellation) was associated with a constellation that was visible in the relevant season: the dragon in the spring, the bird in the summer, etc. Since these four animals — birds, dragons, snakes and tigers — predominate the finds at Sanxingdui, the bronzes could represent the universe. It is unclear whether they formed part of ritual events designed to communicate with the spirits of the universe (or ancestral spirits). As no written records remain it is difficult to determine the intended uses of objects found. Some believe that the continued prevalence of depictions of these animals, especially in the later Han period, was an attempt by humans to "fit into" their understanding of their world. (The jades that were found at Sanxingdui also seem to correlate with the six known types of ritual jades of ancient China, again each associated with a compass point (N, S, E, W) plus the heavens and earth.)

Images

Gold Sheath.

Gold Sheath. Sanxingdui Bronze heads

Sanxingdui Bronze heads Sanxingdui Bronze masks.

Sanxingdui Bronze masks. Bronze animal masks

Bronze animal masks Bronze bird

Bronze bird Sanxingdui bronze head of a bird

Sanxingdui bronze head of a bird

Bird-Headed Handle

Bird-Headed Handle

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mystery of Ancient Chinese Civilization's Disappearance Explained

- 1 2 Sage, Steven F. (1992). Ancient Sichuan and the unification of China. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 16. ISBN 0791410374.

- ↑ Michael Loewe, Edward L. Shaughness. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- ↑ Jessica Rawson. "New discoveries from the early dynasties". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ "Archaeological Sites of the Ancient Shu State: Site at Jinsha and Joint Tombs of Boat- shaped Coffins in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province; Site of Sanxingdui in Guanghan City, Sichuan Province 29C.BC-5C.BC". UNESCO. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ al.], Angela Falco Howard ... [et (2006). Chinese sculpture. New Haven [u.a.]: Yale University Press [u.a.] ISBN 0300100655.

- ↑ Shiji Original text: 武王曰:「嗟!我有國冢君,司徒、司馬、司空,亞旅、師氏,千夫長、百夫長,及庸、蜀、羌、髳、微、纑、彭、濮人,稱爾戈,比爾干,立爾矛,予其誓。」

- ↑ Chronicles of Huayang Original text: 周失紀綱,蜀先稱王。有蜀侯蠶叢,其目縱,始稱王。

- ↑ Sanxingdui Museum (2006), pp. 7-8

- ↑ Yinke, Deng; Martha Avery; Yue Pan (2001). History of China. 五洲传播出版社. p. 171. ISBN 7-5085-1098-4.

- ↑ The Sanxingdui site. translated by Zhao Baohua. China Intercontinental press. 2006. p. 15. ISBN 978-7508508528.

- ↑ Yingke,2001

- ↑ Measurements and date from Xu (2001: 85).

- ↑ Higham, Charles F.W. (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. New York: Facts On File. p. 297. ISBN 1438109962.

- ↑ World Monuments Fund - San Xing Dui Archaeological Site

- ↑ Flad, Rowan; Chen, Pochan (2013). Ancient Central China: Centers and Peripheries Along the Yangtze River. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 89-90. ISBN 978-0-521-72766-2.

- 1 2 Sanxingdui Museum (2006)

- 1 2 Zhuan Ti. "Jinsha, Sanxingdui ruins open up gateway to past". China Daily. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ Xu (2001:66)

- 1 2 Liu (2000:37)

- ↑ (compare Paper 1995:82)

- ↑ Carr (2007:401)

- ↑ Carr (2007:403)

References

- Bagley, Robert, ed. 2001. Ancient Sichuan: Treasures from a Lost Civilization. Princeton, NJ: Seattle Art Museum and Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08851-9

- Carr, Michael. 2007. "The Shi 'Corpse/Personator' Ceremony in Early China," in Marcel Kujistan, ed., Reflections on the Dawn of Consciousness: Julian Jaynes's Bicameral Mind Theory Revisited, Julian Jaynes Society, 343-416.

- Liu Yang and Edmund Capon, eds. 2000. Masks of Mystery: Ancient Chinese Bronzes from Sanxingdui. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales. ISBN 0-7347-6316-6

- Paper, Jordan D. 1995. The Spirits Are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese Religion. State University of New York Press.

- Xu, Jay. 2001. "Bronze at Sanxingdui," in Robert Bagley, ed., Ancient Sichuan: Treasures from a Lost Civilization, Seattle Art Museum and Princeton University Press, 59–152.

- Yinke, Deng; Martha Avery; Yue Pan (2001). History of China. 五洲传播出版社. p. 171. ISBN 7-5085-1098-4.

- Sanxingdui Museum; Wu Weixi; Zhu Yarong (2006). The Sanxingdui site: mystical mask on ancient Shu Kingdom. 五洲传播出版社. p. 134. ISBN 7-5085-0852-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- More About the Finds at Sanxingdui, National Gallery of Art

- Treasures from a Lost Civilization: Ancient Chinese Art from Sichuan, Seattle Art Museum

- Riddle from the Ancient Past: The Mysteries of Sanxingdui, Taiwan Panorama

- Sanxingdui mask relics record traces of Bronze Age, Shanghai Star