Tohono O'odham

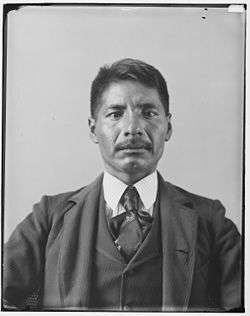

Joe Lewis, Tohono O'odham, 1907 or earlier, Smithsonian Institution | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

United States (Arizona) Mexico (Sonora) | |

| Languages | |

| O'odham, English, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Catholic, Protestant, Traditional | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Piman peoples |

The Tohono O’odham (/toʊˈhɑːnə

The Tohono O’odham tribal government and most of the people have rejected the customary English name Papago, used by Europeans after being adopted by Spanish conquistadores from hearing other Piman bands call them this. The Pima were competitors and referred to the people as Ba:bawĭkoʼa, meaning "eating tepary beans." That word was pronounced papago by the Spanish and adopted by later English speakers.

The Tohono O'odham Nation, or Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation, is a major reservation located in southern Arizona, encompassing portions of Pima County, Pinal County, and Maricopa County.

Culture

The Tohono O’odham share linguistic and cultural roots with the closely related Akimel O'odham (People of the River), whose lands lie just south of present-day Phoenix, along the lower Gila River. The Sobaipuri are ancestors to both the Tohono O’odham and the Akimel O’odham, and they resided along the major rivers of southern Arizona. Ancient pictographs adorn a rock wall that juts up out of the desert near the Baboquivari Mountains.

Debates surround the origins of the O’odham. Claims that the O’odham moved north as recently as 300 years ago compete with claims that the Hohokam, who left the Casa Grande Ruins, are their ancestors. Recent research on the Sobaipuri, the now extinct relatives of the O'odham, shows that they were present in sizable numbers in the southern Arizona river valleys in the fifteenth century.

In the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library are materials collected by a Franciscan friar who worked among the Tohono O'odham. These include scholarly volumes and monographs.[3] The Office of Ethnohistorical Research, located at the Arizona State Museum on the campus of the University of Arizona, has undertaken a documentary history of the O'odham, offering translated colonial documents that discuss Spanish relations with the O'odham in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[4]

Historically, the O'odham-speaking peoples were at odds with the nomadic Apache from the late seventeenth until the beginning of the twentieth centuries. The O'odham were a settled agricultural people who raised crops. According to their history, the Apache would raid when they ran short on food, or hunting was bad. Conflict with European settlers encroaching on their lands resulted in the O'odham and the Apache finding common interests. The O'odham word for the Apache 'enemy' is ob. The relationship between the O'odham and Apache was especially strained after 92 O'odham joined the Mexicans and Anglo-Americans and killed close to 144 Apaches during the Camp Grant massacre in 1871. All but eight of the dead were women and children; 29 children were captured and sold into slavery in Mexico by the O'odham.

Considerable evidence suggests that the O'odham and Apache were friendly and engaged in exchange of goods and marriage partners before the late seventeenth century. O'odham oral history, however, suggests that intermarriages resulted from raiding between the two tribes. It was typical for women and children to be taken captive in raids, to be used as slaves by the victors. Often women married into the tribe in which they were held captive and assimilated under duress. Both tribes thus incorporated "enemies" and their children into their cultures.

O'odham musical and dance activities lack "grand ritual paraphernalia that call for attention" and grand ceremonies such as pow-wows. Instead, they wear muted white clay. O'odham songs are accompanied by hard wood rasps and drumming on overturned baskets, both of which lack resonance and are "swallowed by the desert floor." Dancing features skipping and shuffling quietly in bare feet on dry dirt, the dust raised being believed to rise to atmosphere and assist in forming rain clouds.[5]

The original O'odham diet consisted of regionally available wild game, insects, and plants. Through foraging, O'odham ate a variety of regional plants, such as: ironwood seed, honey mesquite, hog potato, and organ-pipe cactus fruit. While the Southwestern United States did not have an ideal climate for cultivating crops, O'odham cultivated crops of white tepary beans, Papago peas, and Spanish watermelons. They hunted Pronghorn antelope, gathered hornworm larvae, and trapped pack rats for sources of meat. Preparation of foods included steaming plants in pits and roasting meat on an open fire.[6]

The San Xavier District is the location of a major tourist attraction near Tucson, Mission San Xavier del Bac, the "White Dove of the Desert," founded in 1700 by the Jesuit missionary and explorer Eusebio Kino. Both the first and current church building were constructed by the Tohono O'odham. The second building was constructed also by Franciscan priests during a period extending from 1783 to 1797. The oldest European building in the current Arizona, it is considered a premier example of Spanish colonial design. It is one of many missions built in the southwest by the Spanish on their then-northern frontier.

The beauty of the mission often leads tourists to assume that the desert people had embraced the Catholicism of the Spanish conquistadors. Tohono O'odham villages resisted change for hundreds of years. During the 1660s and in 1750s, two major rebellions rivaled in scale the 1680 Pueblo Rebellion. Their armed resistance prevented the Spanish from increasing their incursions into the lands of Pimería Alta. The Spanish retreated to what they called Pimería Baja. As a result, the desert people preserved their traditions largely intact for generations.

It was not until more numerous Americans of Anglo-European ancestry began moving into the Arizona territory that the outsiders began to oppress the people's traditional ways. Major farmers established the cotton industry, initially employing many O'odham as agricultural workers. Under U.S. Federal Indian policy from the late 19th century, the government required native children to attend Indian boarding schools, where they were forced to use English, practice Christianity, and give up much of their culture in an attempt to promote assimilation into the American mainstream.

The structure of the current tribal government, established in the 1930s, reflects years of commercial, missionary, and federal intervention. The goal was to make the Indians into "real" Americans, yet the boarding schools offered training only for low-level domestic and agricultural labor.[7] "Assimilation" was the official policy, but full participation was not the goal. Boarding school students were supposed to function within the segregated society of the United States as economic laborers, not leaders.[8]

The Tohono O'odham have retained many traditions into the twenty-first century, and still speak their language. Since the late 20th century, however, American mass culture has penetrated and in some cases eroded O'odham traditions as their children adopt new trends in technology and other practices.

Health

Beginning in the 1960s, many tribal members abandoned the traditional plant-based diet and began to consume foods high in fat and calories, with the result that type 2 diabetes became widespread among the tribe.[9] Half to three-quarters of all adults are diagnosed with the disease, and about a third of the tribe's adults require regular medical treatment. Federal medical programs have not provided solutions for these problems within the population. Some tribal members have returned to the consumption of traditional foods and practice of traditional games in order to control the obesity that often leads to diabetes. Research by Gary Paul Nabhan and others shows that traditional foods and much more physical exercise better regulated blood sugar. A local nonprofit, Tohono O'Odham Community Action (TOCA), has built a set of food systems programs that contribute to public health, cultural revitalization, and economic development. It has started a cafe that serves traditional foods.[10]

Cultural revitalization

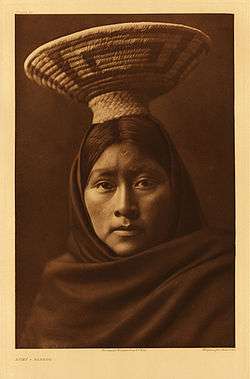

photograph by Edward Curtis circa 1905

The cultural resources of the Tohono O'odham are threatened—particularly the language—but are stronger than those of many other aboriginal groups in the United States.

Every February the Nation holds the annual Sells Rodeo and Parade in its capital. Sells District rodeo has been an annual event since being founded in 1938. It celebrates traditional frontier skills of riding and managing cattle.

In the visual arts, Michael Chiago and the late Leonard Chana have gained widespread recognition for their paintings and drawings of traditional O'odham activities and scenes. Chiago has exhibited at the Heard Museum and has contributed cover art to Arizona Highways magazine and University of Arizona Press books. Chana illustrated books by Tucson writer Byrd Baylor and created murals for Tohono O'odham Nation buildings.

In 2004, the Heard Museum awarded Danny Lopez its first heritage award, recognizing his lifelong work sustaining the desert people's way of life.[11] At the National Museum for the American Indian (NMAI), the Tohono O'odham were represented in the founding exhibition and Lopez blessed the exhibit.

Tucson Indian School

The Tohono O'odham children were required to attend Indian boarding schools, designed to teach them the English language and assimilate them to the mainstream European-American ways. According to historian David Leighton, of the Arizona Daily Star newspaper, the Tohono O'odham attended the Tucson Indian School. This boarding school was founded in 1886, when T.C. Kirkwood, superintendent of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church, asked the Tucson Common Council for land near where the University of Arizona would be built. The Common Council granted the Board of Home Missions a 99-year lease on land at $1 a year. The Board purchased 42 acres of land on the Santa Cruz River, from early pioneer Sam Hughes.

The new facility opened in 1888, with 54 boys and girls. At the new semi-religious boarding school, boys learned rural trades like carpentry and farming, while girls were taught sewing and similar domestic skills of the period. In 1890, additional buildings were completed but the school was still too small for the demand, and students had to be turned away. To raise funds for the school and support its expansion, its superintendent entered into a contract with the city of Tucson to grade and maintain streets.

In 1903, Jose Xavier Pablo, who later went on to become a leader in the Tohono O'odham Nation, graduated from the school. Three years later, the school bought the land they were leasing from the city of Tucson and sold it as a significant profit. In 1907, they purchased land just east of the Santa Cruz River, near present-day Ajo Way and built a new school. The new boarding school opened in 1908; it has a separate post office, known as the Escuela Post Office. Sometimes this name was used in place of the Tucson Indian School.

By the mid-1930s, the Tucson Indian School covered 160 acres, had 9 buildings and a capacity of educating 130 students. In 1940, about 18 different tribes made up the population of students at the school. With changing ideas about education of tribal children, the federal government began to support education where the children lived with their families. In 1960 the school closed its doors. The site was developed as Santa Cruz Plaza, just southwest of Pueblo Magnet High School.[12]

Tohono O'odham Nation

The Tohono O’odham Nation within the United States occupies a reservation that incorporates a portion of its people’s original Sonoran desert lands. It is organized into eleven districts. The land lies in three counties of the present-day state of Arizona: Pima, Pinal, and Maricopa. The reservation’s land area is 11,534.012 square kilometres (4,453.307 sq mi), the third-largest Indian reservation area in the United States (after the Navajo Nation and the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation). The 2000 census reported 10,787 people living on reservation land. The tribe’s enrollment office tallies a population of 25,000, with 20,000 living on its Arizona reservation lands.

Government

The nation is governed by a tribal council and chairperson, who are elected by eligible adult members of the nation. According to their constitution, elections are conducted under a complex formula intended to ensure that the rights of small O’odham communities are protected, as well as the interests of the larger communities and families. The present chairman is Edward D. Manuel.

Lands

- The main reservation, Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation, which lies in central Pima, southwestern Pinal, and southeastern Maricopa counties, and has a land area of 11,243.098 square kilometres (4,340.984 sq mi) and a 2000 census population of 8,376 persons. The land area is 97.48 percent of the reservation's total, and the population is 77.65 percent of the total of the entire reservation lands.

- The San Xavier Reservation, at 32°03′00″N 111°05′02″W / 32.05000°N 111.08389°W, is located in Pima County, in the southwestern part of the Tucson metropolitan area. It has a land area of 288.895 square kilometres (111.543 sq mi) and a resident population of 2,053 persons.

- The San Lucy District comprises seven small non-contiguous parcels of land in, and northwest of, the town of Gila Bend in southwestern Maricopa County. Their total land area is 1.915 square kilometres (473 acres), with a total population of 304 persons.

- The Florence Village District is located just southwest of the town of Florence in central Pinal County. It is a single parcel of land with an area of 0.1045 square kilometres (25.8 acres) and a population of 54 persons.

Border issues

Most of the 25,000 Tohono O'odham today live in southern Arizona. Several thousand of the O'odham, many related by kinship, also live in northern Sonora, Mexico. Unlike aboriginal groups along the U.S.-Canada border, the Tohono O'odham were not offered dual citizenship when the US drew a border across their lands in 1853 by the Gadsden Purchase. Even so, for decades members of the nation moved freely across the current international boundary – with the blessing of the U.S. government – to work, participate in religious ceremonies, keep medical appointments in Sells, Arizona and visit relatives. Even today, many tribal members make an annual pilgrimage to Magdalena, Sonora, during St. Francis festivities to commemorate St. Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan Order.

Since the mid-1980s, however, the United States has conducted stricter border enforcement that restricts this movement, because of issues of drugs and illegal immigration. Tribal members born in Mexico or who have insufficient documentation to prove U.S. birth or residency, have found themselves trapped in a remote corner of Mexico, with no access to the tribal centers only tens of miles away. Since 2001, bills have repeatedly been introduced in Congress to solve the "one people-two country" problem by granting U.S. citizenship to all enrolled members of the Tohono O'odham, but so far their sponsors have not gained passage.[13][14] Opponents of granting U.S. citizenship to all enrolled members of the Nation include concerns that many births on the reservation have been informally recorded, and the records are susceptible to easy alteration or falsification.

The tribal government incurs extra costs due to the proximity of the U.S.-Mexico border. There are also associated social problems. Many of the thousands of Mexican nationals, and other nationals illegally crossing the U.S. Border to work in U.S. agriculture or to smuggle illicit drugs into the U.S., seek emergency assistance from the Tohono O'odham police when they become dehydrated or get stranded. On the ground, border patrol emergency rescue and tribal EMTs coordinate and communicate. The tribe and the state of Arizona pay a large proportion of the bills for border-related law enforcement and emergency services. The former governor of Arizona, Janet Napolitano, and Tohono O'odham government leaders have requested repeatedly that the federal government repay the state and the tribe for the costs of border-related emergencies. Tribe Chairman Ned Norris Jr. has complained about the lack of reimbursement for border enforcement.[15]

Citing the impact it would have on wildlife and on the tribe's members, Tohono O'odham tribal leaders have expressed opposition to President Donald J. Trump's stated plan to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.[16] Approximately 2,000 members live in Mexico, a wall would physically separate them from members in the United States.[17]

Martin Luther King Jr's first visit to an Indian reservation

On April 2, 2017, in the Arizona Daily Star newspaper, noted historian David Leighton related what is believed to be Martin Luther King Jr's first visit to an Indian reservation, which was the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation.

On Sept. 20, 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. flew to Tucson from Los Angeles to give a talk at the Sunday Evening Forum. On that night, he gave a speech called "A Great Time To Be Alive," at the University of Arizona auditorium, now called Centennial Hall. Following the forum, a reception was held for King, in which he was introduced to Rev. Casper Glenn, the pastor of a multiracial church called the Southside Presbyterian Church. King was very interested in this racially mixed church and made arrangements to visit it the next day.

The following morning, Glenn picked up King, in his Plymouth station wagon, and drove him to the Southside Presbyterian Church. There, Glenn showed King photographs he had taken of the racially diverse congregation, most of whom were part of the Tohono O'odham tribal group at the time. Glenn remembers that upon seeing the photos, "King said he had never been on an Indian reservation, nor had he ever had a chance to get to know any Indians." He then requested to be driven to the nearby reservation, as a spur-of-the-moment desire.

The two men traveled on Ajo Way to Sells, on what was then called the Papago Indian Reservation, now the Tohono O'odham Indian Reservation. When they arrived at the tribal council office, the tribal leaders were surprised to see King and very honored he had come to visit them. King was very anxious to talk to them but was very careful with his questions, as he didn't want to show his lack of knowledge of their tribal heritage. "He was fascinated by everything that they shared with him," Glenn said.

The ministers then went to the local Presbyterian church in Sells, which had been recently constructed by its members, with funds provided by the national Presbyterian church. King had a chance to speak to Pastor Towsand who was excited to meet King.

On the way back to Tucson, "King expressed his appreciation of having the opportunity to meet the Indians," Glenn recalled. King left town that day, around 4 pm, from the airport.[18]

Districts

- Gu Achi District

- Pisinemo District

- Sif Oidak District

- Sells District

- Baboquivari District

- Hickiwan District

- San Lucy District

- Gu Vo District

- Chukut Kuk District

- San Xavier District

- Schuk Toak District

Notable Tohono O'odham

- Annie Antone, contemporary, pictorial basketweaver

- Terrol Dew Johnson, basketweaver and native food and health advocate

- Augustine Lopez, Tohono O'odham nation chairman

- Ponka-We Victors, Kansas state legislator

- Ofelia Zepeda, linguist, poet, writer

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ American Indian, Alaska Native Tables from the Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2004–2005 Archived 2012-10-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Volante, Enric. "Respectful ways go a long ways on Ariz. Indian lands". Arizona Daily Star / Tucson Newspapers. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

Hedding, Judy. "How To Pronounce the Names of Indian Tribes". About.com. Retrieved 26 May 2014. - ↑ Kiernan F. McCarthy OFM Collection, Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library http://www.sbmal.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/SBMAL_McCarty.pdf

- ↑ See the special issue of Journal of the Southwest, Vol. 56, No. 2 (Summer 2014), entitled "O'odham and the Pimería Alta."

- ↑ Zepeda, Ofelia (1995). Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert, p.89. ISBN 0-8165-1541-7.

- ↑ Nebhan, Gary Paul (1997). Cultures of Habitat: On Nature, Culture, and Story, pp.197-206.

- ↑ Banks, Dennis & Yuri Morita (1993). Seinaru Tamashii: Gendai American Indian Shidousha no Hansei, Japan, Asahi Bunko.

- ↑ The American Indian Heritage Support Center, official website

- ↑ Block, Deborah (November 25, 2009). "Native American Tribe Has Highest Rate of Adult Onset Diabetes Worldwide". Voice of America. voanews.com. Retrieved 2017-2-23.

- ↑ "TOCA Website". Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ↑ "Spirit of the Heard Award". Heard Museum. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Leighton, David (Feb 9, 2015). "Street Smarts: Tucson Indian School taught hoeing, sewing". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Duarte, Carmen (May 30, 2001). "Nation Divided". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ "H.R.1680 - Tohono O'odham Citizenship Act of 2013". 113th United States Congress (2013-2014). Sponsored by Raul M. Grijalva. Congress.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ McCombs, Brady (2007-08-19). "O'odham leader vows no border fence". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Yashar Ali (6 November 2016). "Trump's Border Wall Will Have a 75-Mile Gap In It". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Santos, Fernanda (2017-02-20). "Border Wall Would Cleave Tribe, and Its Connection to Ancestral Land". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ↑ Leighton, David (April 2, 2017). "Street Smarts: MLK Jr. raised his voice to the rafters in Tucson". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

Further reading

- Frances Manuel and Deborah Neff, Desert Indian Woman. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2001.

- Wesley Bliss, "In the Wake of the Wheel: Introduction of the Wagon to the Papago Indians of Southern Arizona," in E.H. Spicer (ed.), Human Problems in Technological Change. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications, 1952; pp. 23–33.

- Eloise David and Marcia Spark, "Arizona Folk Art Recalls History of Papago Indians," The Clarion, Fall 1978.

- Jason H. Gart, Papago Park: A History of Hole-in-the-Rock from 1848 to 1995. Pueblo Grande Museum Occasional Papers No. 1, (1997).

- Andrae M. Marak and Laura Tuennerman, At the Border of Empires: The Tohono O'odham, Gender, and Assimilation, 1880-1934. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2013.

- Allan J. McIntyre, The Tohono O'odham and Pimeria Alta. Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

- Deni J. Seymour, "A Syndetic Approach to Identification of the Historic Mission Site of San Cayetano Del Tumacácori," International Journal of Historical Archaeology, vol. 11, no. 3 (2007), pp. 269–296.

- Deni J. Seymour, "Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part I." New Mexico Historical Review, vol. 82, no. 4 (2007).

- Deni J. Seymour, "Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part II." New Mexico Historical Review, vol. 83, no. 2 (2008).

- David Leighton, "Street Smarts: Tucson Indian School taught hoeing, sewing," Arizona Daily Star, Feb. 10, 2015

- David Leighton, "Street Smarts: MLK Jr. raised his voice to the rafters in Tucson," Arizona Daily Star, April 2, 2017

External links

- Official Website of the Tohono O'odham Nation

- Tohono O'odham / ITCA (Inter Tribal Council of Arizona)

- Tohono O'odham Community Action (TOCA)

- TOCA's Desert Rain Cafe

- How To Speak Tohono O'odham – Video

- Tohono O'odham utilities

- O'odham Solidarity Project

- Online Tohono O'odham bibliography

- Tohono O'odham, Papago in Sonora, Mexico

- David Leighton, "Street Smarts: Tucson Indian School taught hoeing, sewing," Arizona Daily Star, Feb. 10, 2015