Tiwanaku

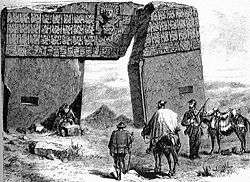

The "Gate of the Sun" | |

Shown within Bolivia | |

| Alternative name | Tiahuanaco, Tiahuanacu |

|---|---|

| Location | Tiwanaku Municipality, Bolivia |

| Coordinates | 16°33′17″S 68°40′24″W / 16.55472°S 68.67333°WCoordinates: 16°33′17″S 68°40′24″W / 16.55472°S 68.67333°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Cultures | Tiwanaku empire |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

| Official name | Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku Culture |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 2000 (24th session) |

| Reference no. | 567 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Tiwanaku (Spanish: Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu) is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia near Lake Titicaca and one the largest sites in the South America. Surface remains currently cover around 4 square kilometers and include decorated ceramics, monumental structures, and megalithic blocks. The site's population probably peaked around AD 800 with 10,000 to 20,000 people.[1]

The site was first recorded in written history in 1549 by Spanish conquistador Pedro Cieza de León while searching for the southern Inca capital of Qullasuyu.[2]

Antiquity

The age of the site has been significantly refined over the last century. From 1910 to 1945, Arthur Posnansky maintained that the site was 11,000–17,000 years old[3][4] based on comparisons to geological eras and archaeoastronomy. Beginning in the 1970s, Carlos Ponce Sanginés proposed the site was first occupied around 1580 BC[5], the site's oldest radiocarbon date. This date is still seen in some publications and museums in Bolivia. Since the 1980s, researchers have recognized this date as unreliable, leading to the consensus that the site is no older than 200 or 300 BC[6][7][8]. Most recently, a statistical assessment of reliable radiocarbon dates estimates that the site was founded around AD 110 (50–170, 68% probability)[9], a date supported by the lack of ceramic styles from earlier periods[10].

Structures

The structures that have been excavated by researchers at Tiwanaku include the Akapana, Akapana East, and Pumapunku stepped platforms, the Kalasasaya, the Kheri Kala, and Putuni enclosures, and the Semi-Subterranean Temple. These may be visited by the public.

The Akapana is an approximately cross-shaped pyramidal structure that is 257 m wide, 197 m broad at its maximum, and 16.5 m tall. At its center appears to have been a sunken court. This was nearly destroyed by a deep looters excavation that extends from the center of this structure to its eastern side. Material from the looters excavation was dumped off the eastern side of the Akapana. A staircase with sculptures is present on its western side. Possible residential complexes might have occupied both the northeast and southeast corners of this structure.

Originally, the Akapana was thought to have been developed from a modified hill. Twenty-first-century studies have shown that it is an entirely manmade earthen mound, faced with a mixture of large and small stone blocks. The dirt comprising Akapana appears to have been excavated from the "moat" that surrounds the site.[11] The largest stone block within the Akapana, made of andesite, is estimated to weigh 65.70 metric tons.[12] The structure was possibly for the shaman-puma relationship or transformation through shape shifting. Tenon puma and human heads stud the upper terraces.[11]

The Akapana East was built on the eastern side of early Tiwanaku. Later it was considered a boundary between the ceremonial center and the urban area. It was made of a thick, prepared floor of sand and clay, which supported a group of buildings. Yellow and red clay were used in different areas for what seems like aesthetic purposes. It was swept clean of all domestic refuse, signaling its great importance to the culture.[11]

The Pumapunku is a man-made platform built on an east–west axis like the Akapana. It is a rectangular, terraced earthen mound faced with megalithic blocks. It is 167.36 m wide along its north–south axis and 116.7 m broad along its east–west axis, and is 5 m tall. Identical 20-meter-wide projections extend 27.6 meters north and south from the northeast and southeast corners of the Pumapunku. Walled and unwalled courts and an esplanade are associated with this structure.

A prominent feature of the Pumapunku is a large stone terrace; it is 6.75 by 38.72 meters in dimension and paved with large stone blocks. It is called the "Plataforma Lítica". The Plataforma Lítica contains the largest stone block found in the Tiwanaku site.[12][13] According to Ponce Sangines, the block is estimated to weigh 131 metric tons.[12] The second-largest stone block found within the Pumapunku is estimated to be 85 metric tons.[12][13]

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard more than 300 feet long, outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana and west of the Semi-Subterranean Temple. Within the courtyard is where explorers found the Gateway of the Sun. Since the late 20th century, researchers have theorized that this was not the gateway's original location.

Near the courtyard is the Semi-Subterranean Temple; a square sunken courtyard that is unique for its north–south rather than east–west axis.[14] The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles, suggesting that the structure was reused for different purposes over time.[15] It was built with walls of sandstone pillars and smaller blocks of Ashlar masonry.[15][16] The largest stone block in the Kalasasaya is estimated to weigh 26.95 metric tons.[12]

.jpg)

Within many of the site's structures are impressive gateways; the ones of monumental scale are placed on artificial mounds, platforms, or sunken courts. Many gateways show iconography of the Staff God. This iconography also is used on some oversized vessels, indicating an importance to the culture. This iconography is most present on the Gateway of the Sun.[17]

The Gateway of the Sun and others located at Pumapunku are not complete. They are missing part of a typical recessed frame known as a chambranle, which typically have sockets for clamps to support later additions. These architectural examples, as well as the recently discovered Akapana Gate, have a unique detail and demonstrate high skill in stone-cutting. This reveals a knowledge of descriptive geometry. The regularity of elements suggest they are part of a system of proportions.

Many theories for the skill of Tiwanaku's architectural construction have been proposed. One is that they used a luk’a, which is a standard measurement of about sixty centimeters. Another argument is for the Pythagorean Ratio. This idea calls for right triangles at a ratio of five to four to three used in the gateways to measure all parts. Lastly Protzen and Nair argue that Tiwanaku had a system set for individual elements dependent on context and composition. This is shown in the construction of similar gateways ranging from diminutive to monumental size, proving that scaling factors did not affect proportion. With each added element, the individual pieces were shifted to fit together.[18]

As the population grew, occupational niches developed, and people began to specialize in certain skills. There was an increase in artisans, who worked in pottery, jewelry and textiles. Like the later Inca, the Tiwanaku had few commercial or market institutions. Instead, the culture relied on elite redistribution.[19] That is, the elites of the empire controlled essentially all economic output, but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function. Selected occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Such separation of occupations was accompanied by hierarchical stratification within the empire.[20]

The elites of Tiwanaku lived inside four walls that were surrounded by a moat. This moat, some believe, was to create the image of a sacred island. Inside the walls were many images devoted to human origin, which only the elites would see. Commoners may have entered this structure only for ceremonial purposes, since it was home to the holiest of shrines.[2]

Archaeology

As the site has suffered from looting and amateur excavations since shortly after Tiwanaku's fall, archeologists must attempt to interpret it with the understanding that materials have been jumbled and destroyed. This destruction continued during the Spanish conquest and colonial period, and during 19th century and the early 20th century. Other damage was committed by people quarrying stone for building and railroad construction, and target practice by military personnel.

No standing buildings have survived at the modern site. Only public, non-domestic foundations remain, with poorly reconstructed walls. The ashlar blocks used in many of these structures were mass-produced in similar styles so that they could possibly be used for multiple purposes. Throughout the period of the site, certain buildings changed purposes, causing a mix of artifacts found today.[18]

Detailed study of Tiwanaku began on a small scale in the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1860s, Ephraim George Squier visited the ruins and later published maps and sketches completed during his visit. German geologist Alphons Stübel spent nine days in Tiwanaku in 1876, creating a map of the site based on careful measurements. He also made sketches and created paper impressions of carvings and other architectural features. A book containing major photographic documentation was published in 1892 by engineer B. von Grumbkow. With commentary by archaeologist Max Uhle, this was the first in-depth scientific account of the ruins.

- Pictures of archaeological excavations in 1903

Stairs of Kalasasaya (1903)

Stairs of Kalasasaya (1903) Temple of Kalasasaya (1903)

Temple of Kalasasaya (1903)_1903-1904.jpg) Gate of the Sun (1903)

Gate of the Sun (1903) Gate of the Sun, Rear View (1903)

Gate of the Sun, Rear View (1903)

Contemporary excavation and restoration

In the 1960s, the Bolivian government initiated an effort to restore the site and reconstruct part of it. The walls of the Kalasasaya are almost all reconstructed. The original stones making up the Kalasasaya would have resembled a more "Stonehenge"-like style, spaced evenly apart and standing straight up. The reconstruction was not sufficiently based on research; for instance, a new wall was built around Kalasasaya. The reconstruction does not have as high quality of stonework as was present in Tiwanaku.[15] As noted, the Gateway of the Sun, now in the Kalasasaya, was moved from its original location.[2]

Modern, academically sound archaeological excavations were performed from 1978 through the 1990s by University of Chicago anthropologist Alan Kolata and his Bolivian counterpart, Oswaldo Rivera. Among their contributions are the rediscovery of the suka kollus, accurate dating of the civilization's growth and influence, and evidence for a drought-based collapse of the Tiwanaku civilization.

Archaeologists such as Paul Goldstein have argued that the Tiwanaku empire ranged outside of the altiplano area and into the Moquegua Valley in Peru. Excavations at Omo settlements show signs of similar architecture characteristic of Tiwanaku, such as a temple and terraced mound.[14] Evidence of similar types of cranial vault modification in burials between the Omo site and the main site of Tiwanaku is also being used for this argument.[21]

Today Tiwanaku has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, administered by the Bolivian government.

Recently, the Department of Archaeology of Bolivia (DINAR, directed by Javier Escalante) has been conducting excavations on the Akapana pyramid. The Proyecto Arqueologico Pumapunku-Akapana (Pumapunku-Akapana Archaeological Project, PAPA) run by the University of Pennsylvania, has been excavating in the area surrounding the pyramid for the past few years, and also conducting Ground Penetrating Radar surveys of the area.

In former years, an archaeological field school offered through Harvard's Summer School Program, conducted in the residential area outside the monumental core, has provoked controversy amongst local archaeologists.[22] The program was directed by Dr. Gary Urton,[23] of Harvard, who was an expert on quipus, and Dr. Alexei Vranich of the University of Pennsylvania. The controversy was over allowing a team of untrained students to work on the site, even under professional supervision. It was so important that only certified professional archaeologists with documented funding were allowed access. The controversy was charged with nationalistic and political undertones.[24] The Harvard field school lasted for three years, beginning in 2004 and ending in 2007. The project was not renewed in subsequent years, nor was permission sought to do so.

In 2009 state-sponsored restoration work on the Akapana pyramid was halted due to a complaint from UNESCO. The restoration had consisted of facing the pyramid with adobe, although researchers had not established this as appropriate.[25][26]

See also

References

- ↑ Janusek, John (2004). Identity and Power in the Ancient Andes: Tiwanaku Cities through Time. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415946346.

- 1 2 3 Kolata, Alan L. (1993). The Tiwanaku: Portrait of an Andean Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-183-2.

- ↑ Posnansky, Arthur (1910). Tihuanacu e islas del Sol y de la Luna (Titicaca y Koati). La Paz.

- ↑ Posnansky, Arthur (1945). Tihuanacu, the Cradle of American Man. I–II. Translated by James F. Sheaver. New York: JJ Augustin.

- ↑ Ponce Sanginés, Carlos (1971). Tiwanaku: Espacio, Tiempo y Cultura. La Paz: Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- ↑ Browman, David (1980). "Tiwanaku expansion and economic patterns". Estudios Arqueológicos. 5: 107–120.

- ↑ Janusek, John (2003). "Vessels, Time, and Society: Toward a Ceramic Chronology in the Tiwanaku Heartland". In Kolata, Alan. Tiwanaku and Its Hinterland: Archaeological and Paleoecological Investigations of an Andean Civilization, Vol. 2: Urban and Rural Archaeology. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian. pp. 30–89.

- ↑ Stanish, Charles (2003). Ancient Titicaca. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ↑ Marsh, Erik (2012). "A Bayesian Re-Assessment of the Earliest Radiocarbon Dates from Tiwanaku, Bolivia". Radiocarbon. 54: 203–218. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.v54i2.15826.

- ↑ Marsh, Erik (2012). "The Founding of Tiwanaku: Evidence from Kk'araña". Ñawpa Pacha. 32: 169–188. doi:10.1179/naw.2012.32.2.69.

- 1 2 3 Isbell, W. H., 2004, Palaces and Politics in the Andean Middle Horizon. in S. T. Evans and J. Pillsbury, eds., pp. 191-246. Palaces of the Ancient New World, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ponce Sanginés, C. and G. M. Terrazas, 1970, Acerca De La Procedencia Del Material Lítico De Los Monumentos De Tiwanaku. Publication no. 21. Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- 1 2 Vranich, A., 1999, Interpreting the Meaning of Ritual Spaces: The Temple Complex of Pumapunku, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

- 1 2 Goldstein, Paul (1993). Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moquegua, Peru.

- 1 2 3 Browman, D. L., 1981, "New light on Andean Tiwanaku," New Scientist vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 408-419.

- ↑ Coe, Michael, Dean Snow, and Elizabeth Benson, 1986, Atlas of Ancient America p. 190

- ↑ Silverman, Helaine Andean Archaeology Volume 2. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2004

- 1 2 Protzen, J.-P., and S. E. Nair, 2000, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture": The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 59, no., 3, pp. 358-371.

- ↑ Smith, Michael E. (2004), "The Archaeology of Ancient Economies," Annu. Rev. Anthrop. 33: 73-102.

- ↑ Bahn, Paul G. Lost Cities. New York: Welcome Rain, 1999.

- ↑ Hoshower, Lisa M. (1995). Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru.

- ↑ Lémuz, C (2007), "Buenos Negocios, ¿Buena Arqueologia?", Crítica Arqueológica Boliviana [Bolivian archæological critic] (World Wide Web log) (in Spanish) .

- ↑ "Program in Tiwanaku, Bolivia", Summer School Archives, Harvard University, 2005, archived from the original on 2012-08-05 .

- ↑ Kojan, David; Angelo, Dante, "Dominant narratives, social violence and the practice of Bolivian archaeology", Journal of Social Archaeology, 5 (3): 383–408, doi:10.1177/1469605305057585 .

- ↑ Carroll, Rory (20 October 2009). "Makeover may lose Bolivian pyramid its world heritage site listing". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Pyramid may lose World Heritage status after renovation fiasco". Sydney Morning Herald. October 20, 2009.

Bibliography

- Bermann, Marc Lukurmata Princeton University Press (1994) ISBN 978-0-691-03359-4.

- Bruhns, Karen Olsen, Ancient South America, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, c. 1994.

- Goldstein, Paul, "Tiwanaku Temples and State Expansion: A Tiwanaku Sunken-Court Temple in Moduegua, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 4, No. 1 (March 1993), pp. 22–47, Society for American Archaeology.

- Hoshower, Lisa M., Jane E. Buikstra, Paul S. Goldstein, and Ann D. Webster, "Artificial Cranial Deformation at the Omo M10 Site: A Tiwanaku Complex from the Moquegua Valley, Peru", Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 6, No. 2 (June, 1995) pp. 145–64, Society for American Archaeology.

- Janusek, John Wayne Ancient Tiwanaku Cambridge University Press (2008) ISBN 978-0-521-01662-9.

- Kolata, Alan L., "The Agricultural Foundations of the Tiwanaku State: A View from the Heartland", American Antiquity, Vol. 51, No. 4 (October 1986), pp. 748–762, Society for American Archaeology.

- Kolata, Alan L (June 1991), "The Technology and Organization of Agricultural Production in the Tiwanaku State", Latin American Antiquity, Society for American Archaeology, 2 (2): 99–125, doi:10.2307/972273 .

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre and Stella E. Nair, "On Reconstructing Tiwanaku Architecture", The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 3 (September 2000), pp. 358–71, Society of Architectural Historians.

- Reinhard, Johan, "Chavin and Tiahuanaco: A New Look at Two Andean Ceremonial Centers." National Geographic Research 1(3): 395–422, 1985.

- ——— (1990), "Tiahuanaco, Sacred Center of the Andes", in McFarren, Peter, An Insider's Guide to Bolivia, La Paz, pp. 151–81 .

- ——— (1992), "Tiwanaku: Ensayo sobre su cosmovisión" [Tiwanaku: essay on its cosmovision], Revista Pumapunku (in Spanish), 2: 8–66 .

- Stone-Miller, Rebecca (2002) [c. 1995], Art of the Andes: from Chavin to Inca, London: Thames & Hudson .

- Vallières, Claudine (2013). A Taste of Tiwanaku: Daily Life in an Ancient Andean Urban Center as Seen through Cuisine (Ph.D.). McGill University.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tiwanaku. |

| Library resources about Tiwanaku |

- Map of Ingavi Province, Agua en Bolivia, CGIAB, archived from the original on April 18, 2009, retrieved September 22, 2013

- "Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku Culture", World Heritage List, World Heritage Centre, UNESCO, retrieved September 22, 2013

- Daily Life at Tiwanaku, Archæology student, archived from the original on May 22, 2010, retrieved September 22, 2013

- "Revealing Ancient Bolivia", Archaeology Magazine, Archaeological Institute of America, 2004, retrieved September 22, 2013

- "Geophysics and Geomatics at Tiwanaku", Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas, retrieved September 22, 2013

- Heinrich, P (2008), "Tiwanaku (Tiahuanaco) Site Bibliography", Papers, Hall of Ma’at

- Higueros, A (1999), "Archaeological Research on the Tiwanaku polity in Peru and Bolivia", Arqueologia Andina y Tiwanaku