Tiradentes

| Joaquim José da Silva Xavier (Tiradentes) | |

|---|---|

Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, known as Tiradentes. | |

| Born |

November 12, 1746 Fazenda do Pombal (Ritápolis), Minas Gerais, Portuguese Colony of Brazil |

| Died |

April 21, 1792 (aged 45) Rio de Janeiro, Portuguese Colony of Brazil |

| Other names | Tiradentes |

| Movement | Inconfidência Mineira |

Joaquim José da Silva Xavier (Portuguese pronunciation: [ʒwaˈkĩ ʒuˈzɛ dɐ ˈsiwvɐ ʃɐviˈɛʁ]; November 12, 1746 – April 21, 1792), known as Tiradentes (pronounced [tʃiɾɐˈdẽtʃis]), was a leading member of the Brazilian revolutionary movement known as Inconfidência Mineira, whose aim was full independence from Portuguese colonial power and creation of a Brazilian republic.

When the separatists' plot was uncovered by authorities, Tiradentes was arrested, tried and publicly hanged.

Since the advent of the Brazilian Republic, Xavier has been considered a national hero of Brazil and patron of the Military Police.[1]

Family and early occupation

Xavier was born to a poor family in a farm in Pombal, Ritápolis, near São João del Rey, Minas Gerais. He was adopted by his godfather and moved to Vila Rica (now Ouro Preto) after the death of his parents (mother in 1755; father in 1757).[2]

He was raised by a tutor, who was a surgeon. His lack of formal education didn't stop him from working in several fields, including dental medicine: "Tiradentes" means "tooth puller"[3], a pejorative denomination adopted during the trial against him. He also practiced other varied professions, like herder and miner.

Political ideas

Xavier used knowledge he acquired about minerals while working as a miner to enter the public service as a terrain surveyor.

He later joined the Minas Gerais Dragoon Regiment, where he was given command of a detachment and sent on missions to cities along "Caminho Novo", a road between Vila Rica (then capital of Minas Gerais) and Rio de Janeiro through which gold was sent to the coast, ultimately to be shipped to Portugal.

Over time, witnessing the transit of goods along Caminho Novo, Xavier started to perceive the massive exportation of gold and other valuable resources to the metropolis as exploitation to which Brazilians were subjected. He also grew dissatisfied with his relatively low rank (not a member of the local aristocracy, he was systematically overlooked for promotion and never rose above alferes, the lowest officer rank at the time) and a later dismissal from his commanding post.

His trips to Rio put him in contact with people who had lived in Europe and brought liberal ideas from there.

In 1788, Xavier met José Alvares Maciel, a son of Vila Rica's army's commandant who had just returned from England. Contrasting British industrial progress with Brazilian colonial poverty, the two decided to create a group of freedom aspirants. Led by clerics and other Brazilians with some social presence, like Cláudio Manuel da Costa, Tomás Antônio Gonzaga (both public servants and renowned writers) and Alvarenga Peixoto (eminent businessman), the group propagated their ideas among the people.

At the time, Portugal's demand for gold was high. However, productivity of Brazilian mines was declining. The colony was failing to meet the quinto – the quota of gold demanded by the Crown – and pressure from the metropolis rose. This culminated in the creation of the derrama, a heavily confiscatory tribute that, in turn, further stirred seditious sentiments.

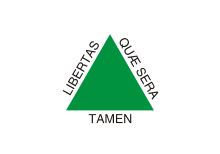

Influenced by the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the American Revolution, Xavier joined a number of like-minded citizens in the Inconfidência Mineira, a revolutionary movement. They envisioned an independent Brazilian republic, with São João del Rei as its capital and the conversion of Vila Rica to an university town. The proposed flag for the new republic had a green triangle over a white background, surrounded by the Latin motto "Libertas Quae Sera Tamen" ("Freedom, Even If It Be Late").

Discovery, trial and execution

Xavier's plan was to take to the streets of Vila Rica and proclaim a Brazilian Republic on the day of the derrama, in February 1789, when tax was due to Portugal and the sentiment of revolt among Brazilians would be stronger. Joaquim Silvério dos Reis, one of the conspirators, exposed the plot in exchange for a tax waiver. The governor of Minas Gerais cancelled the derrama and ordered the imprisonment of the rebels.

A trial was carried, lasting almost three years. Xavier was sentenced to death, along with ten other inconfidentes. Queen Maria I of Portugal later commuted the sentences of capital punishment to perpetual banishment for all convicts, except those whose activities involved aggravated circumstances. Such was the case of Xavier, who took full responsibility for the movement.

He was imprisoned in Rio, then hanged in April 21st, 1792. Afterwards, his body was quartered and the pieces were sent to Vila Rica, to be displayed in places where he used to propagate his liberal ideas.

National hero

Xavier began to be considered a national hero by the republicans in the late 19th century. After the institution of the Republic, in 1889, the anniversary of his death became a national holiday.

His moniker, "Tiradentes", became the namesake of a city in the state of Minas Gerais, of city squares in Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Ouro Preto, as well as of a major avenue in the Dominican Republic.

See also

- Zica family, descendants of Tiradentes

References

- ↑ "PM Antecipa homenagem a Tiradentes, patrono cívico do Brasil". Alerj. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Tiradentes". Brasil Escola. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ↑ from the Portuguese words tirar (to take or remove) and dentes (teeth)

Further reading

- Maxwell, Kenneth R, Conflicts and Conspiracies: Brazil & Portugal 1750-1808 (Cambridge University Press, 1973) ISBN 0-521-20053-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiradentes. |

- Museu da Inconfidência

- Tiradentes at about.com

- Tiradentes at e-Biografias