Thomas Bungay

Thomas Bungay (Latin: Thomas Bungeius or Bungeyensis;[2] c. 1214 – c. 1294),[3] also known as Thomas of Bungay[4] (Latin: Thomas de Bungeya;[5] French: Thomas de Bungeye) and formerly also known as Friar Bongay,[1] was an English Franciscan friar, scholar, and alchemist.[3]

Life

Thomas was born in Bungay, a market town in Suffolk.[6] He was educated at Oxford and Paris in the mid-13th century[6] and, at an unknown date, entered the Order of the Friars Minor (Franciscans) at Norwich.[7] He lectured as the 10th Franciscan "Reader in Divinity" at Oxford,[6] certainly in the years 1270–72,[8] before leaving to serve as the 8th Minister Provincial of the Franciscans in England during the years 1272–75.[7][9] (He was succeeded at Oxford by John Peckham.)[6] From around 1275[7] to at least 1283,[8] he served as the 15th Franciscan master at Cambridge.[10][7] He wrote Quaestio in Aristotelis de Caelo et Mundo, a commentary on Gerard's edition[11] of Aristotle's work On the Heavens.[5][12] Other questions are attributed to him in MS Assisi 158.[7] He died at Northampton, England.[7]

Despite their roughly contemporaneous studies and later legends, no real evidence of a relationship between Bungay and Roger Bacon has yet been discovered.[13]

Legend

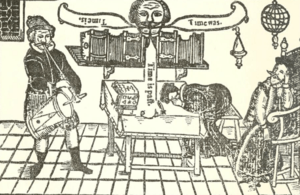

He is better known from later English legend, which made him Roger Bacon's sidekick in the stories that developed around that scholar's knowledge of alchemy and supposed mastery of magic.[1][14][15] In some versions, he is killed by the German mage Vandermast.[14]

Bungay may owe his magical reputation to a separate Friar Bungay, who seems to have been a magician in the 15th century.[16]

Legacy

Bungay serves a similar sidekick role in Doctor Mirabilis, James Blish's fictional biography of Roger Bacon.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay.

- ↑ Personal Names of the Middle Ages, p. 653.

- 1 2 Carr-Gomm; et al., The Book of English Magic, p. 223 .

- ↑ Hartsiotis (2013), p. 59.

- 1 2 Cambridge Gonville & Caius MS 509 (XIII), f. 208–252.

- 1 2 3 4 Serjeantson (1911), p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 CE (2003).

- 1 2 Galle (2003), p. 38.

- ↑ Goad (1979), p. 207.

- ↑ Little, The Friars and Faculty of Theology at Cambridge, pp. 131 ff .

- ↑ Wingate (1931), p. 28.

- ↑ Parker (1968).

- ↑ Little, A.G.; et al. (1934), Oxford Theology and Theologians, Oxford, p. 75 .

- 1 2 The Famous Historie of Frier Bacon.

- ↑ Hartsiotis (2013).

- ↑ Traditio, 1974, p. 449 .

Bibliography

- Bungay, Thomas (1968), "Thomas de Bungeye's Commentary on the First Book of Aristotle's De Caelo", in Parker, Bernard Street, Dissertation Abstracts, Vol. XXIX, No. 5, pp. 105–281 .

- "Thomas of Bungey", New Catholic Encyclopedia, Gale Group, 2003 .

- Galle, Griet (2003), "The Reception of De Caelo in the Thirteenth Century", Peter of Auvergne: Questions on Aristotle's De Caelo: A Critical Edition with an Interpretative Essay, Leuven: Leuven University Press, ISBN 90-5867-322-7 .

- Goad, Harold Elsdale (1979), Grey Friars: The Story of St. Francis and his Followers, Franciscan Herald Press, ISBN 9780819907790 .

- Hartsiotis, Kirsty (2013), "Friar Bungay and the Fair Maid of Fressingfield", Suffolk Folk Tales, History Press, pp. 59–65 .

- Serjeantson, Robert Meyricke (1911), A History of the Six Houses of Friars at Northampton: The Black, White, Grey, and Austin Friars, the Friars of the Sack, and the Poor Clares, J. Tebbutt .

- Wingate, S.D. (1931), The Mediaeval Latin Versions of the Aristotelian Scientific Corpus, with Special Reference to the Biological Works, London: Courier Press .