The Steerage

The Steerage is a photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1907. It has been hailed as one of the greatest photographs of all time because it captures in a single image both a formative document of its time and one of the first works of artistic modernism.

Description

The scene depicts a variety of men and women traveling in the lower-class section of a steamer going from New York to Bremen, Germany. Many years after taking the photograph Stieglitz described what he saw when he took it:

- "There were men and women and children on the lower deck of the steerage. There was a narrow stairway leading to the upper deck of the steerage, a small deck right on the bow of the steamer.

- To the left was an inclining funnel and from the upper steerage deck there was fastened a gangway bridge that was glistening in its freshly painted state. It was rather long, white, and during the trip remained untouched by anyone.

- On the upper deck, looking over the railing, there was a young man with a straw hat. The shape of the hat was round. He was watching the men and women and children on the lower steerage deck…A round straw hat, the funnel leaning left, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railing made of circular chains – white suspenders crossing on the back of a man in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mast cutting into the sky, making a triangular shape…I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life."[1]

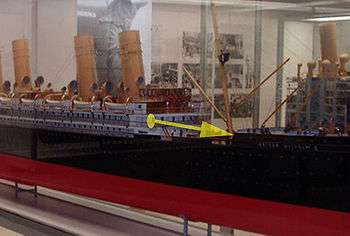

Although Stieglitz described "an inclining funnel" in the scene photographs and models of the ship (see below) show that this object was actually a large mast to which booms were fastened for loading and unloading cargo. One of the booms is shown at the very top of the picture.

Much has been written about scene as a cultural document of an important period when many immigrants were coming to America. In fact, the picture was taken on a cruise to Europe from America, and for that reason some critics have interpreted it as recording people who were turned away by U.S. Immigration officials and were forced to go back home. Although some of the passengers might have been turned back because of failure to meet financial or health requirements for entrance, it is more likely that most of them were various artisans who worked in the booming construction trade of the time. Workers who were highly skilled in crafts such as cabinet-making, woodworking and marble laying were granted two-year temporary visas to complete their jobs and then returned to their homelands when the work was complete.[2]

Taking the photograph

In June 1907 Stieglitz and his family sailed to Europe to visit relatives and friends. They booked passage on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm II, one of the largest and fastest ships in the world at that time.[3] Stieglitz's wife Emmy insisted on first class accommodations, and the family had a fine stateroom on the upper decks. According to Stieglitz, sometime after their third day of travel he went for a walk around the ship and came upon a viewpoint that looked down toward the lower class passengers area, known on most ships as the steerage.[1] Photography historian Beaumont Newhall wrote that it is likely the photo was taken while the ship was anchored at Plymouth, England, because the angle of the shadows indicates it was facing west, not east as it would have been while crossing the ocean. In addition there does not seem to be any sign of wind in the scene, which would have been ever present while the ship was moving.[4]

The scene Stieglitz saw is described above. He did not have his camera with him, and he raced back to his cabin to get it. At that time he was using a hand-held 4×5 Auto-Graflex that used glass plate negatives. Stieglitz found he had only one glass plate prepared at the time, and he quickly returned to the viewpoint and captured the one and only picture of the scene.[5]

He was not able to develop the plate until he arrived in Paris nearly a week later. He reported he went to the Eastman Kodak Company in Paris to use their darkroom but was referred to a local photographer instead. He went to the photographer's home and developed the plate there. The name of the photographer who lent his facility is unknown. Stieglitz offered to pay the photographer for the use of his darkroom and materials but he said the photographer told him, "I know who you are and it's an honor to have you in my darkroom." Stieglitz kept the developed image in its original plate holder to protect it until he returned to New York several weeks later.[1]

Stieglitz later said he immediately recognized this image as "another milestone in photography…a step in my own evolution, a spontaneous discovery",[1] but this claim is challenged by several of his biographers who have pointed out that although he had many opportunities to do so he didn't publish it until 1911 and didn't exhibit it until 1913.[5][6] In addition, biographer Richard Whelan states, "If he really had known that he had just produced a masterpiece, he probably would not have been so depressed during his European vacation that summer [as he indicated in several letters to friends]".[6]

Whelan theorizes that when Stieglitz first looked at the negative he did not see the stylistic qualities he was then championing, and he set the negative aside while dealing with more pressing issues.[5] In the period directly before and after taking The Steerage Stieglitz was still producing photos that were primarily pictorialist in style, and it would be several more years before he began to break with this tradition. The Steerage represents a "fundamental shift in Stieglitz's thinking",[7] and, critics have said that while his mind had visualized the image when he took it he was not able to articulate his reasons for taking it until later.[6] Also, painter Max Weber claims to have discovered the image while looking through Stieglitz's photos in 1910, and he took credit for first pointing out the aesthetic importance of the image.[8] Whether that is true or not, it was only after Stieglitz began to seriously consider the works of modern American artists like John Marin, Arthur Dove and Weber that he finally published the image. Perhaps Stieglitz had seen the 1900 painting with the same title by George Luks (now in NC Museum of Art). Like the works of those artists,The Steerage is "divided, fragmented and flattened into an abstract, nearly cubistic design"[9] and it has been cited as one of the first proto-Cubist works of art.[10][11]

One other distraction could have been a reason why Stieglitz did not immediately publish The Steerage. While he was still in Paris on the same trip he saw for the first time and experimented with the new Autochrome Lumière process, the first commercially viable means of capturing images in color. For the next two years he was captivated by color photography, and he did not return to The Steerage and other black-and-white photos until he learned to photograph using this new process.[5]

First appearances

Stieglitz first published The Steerage in the October 1911 issue of Camera Work, which he had devoted to his own photography. It appeared the following year on the cover of the magazine section of the Saturday Evening Mail (20 April 1912), a New York weekly magazine.

It was first exhibited in a show of Stieglitz's photographs at "291" in 1913.

In 1915 Stieglitz devoted the entire No 7-8 issue of 291 to The Steerage. The only text in the issue were comments on the photo by Paul Haviland and Marius de Zayas.

Design and aesthetics

There have been dozens of critical interpretations of The Steerage since it was first published. Here are some of the most prominent ones:

- "This photographer is working in the same spirit as I am." – Pablo Picasso after having seen The Steerage[12]

- With The Steerage Stieglitz "abandoned the idea that photographs should bear some likeness to paintings and embarked on a new path to explore photos as photos in their own right."[7]

- The Steerage dealt alternately with geometric forms constructed in spatial planes within a photographic frame and issues of social class and gender differences.[13]

- In The Steerage, Stieglitz "demonstrated that essentially 'documentary' photographs could convey transcendental truths and fully embody all of the principles by which any graphic image was deemed 'artistic'.[14]

Versions

According to the Key Set published by the National Gallery of Art[15] there are five known versions of The Steerage:

- A photogravure published in Camera Work, No 36 1911, plate 9 (Key Set #310). The image measures approximately 75⁄8″ × 515⁄16″ (19.5 × 15.1 cm).

- A photogravure identified as a proof of the image published in Camera Work (Key Set #311). The image measures approximately 73⁄4″ × 61⁄4″ (19.7 × 15.8 cm).

- A photogravure exhibited in several exhibitions of Stieglitz's work (Key Set #312). The image measures approximately 131⁄16″ × 105⁄8″ (33.2 × 26.4 cm).

- A photogravure published on Japanese paper as an insert in the deluxe edition of the September–October 1915 issue of 291 (Key Set #313). The image measures approximately 131⁄8″ × 101⁄2″ (33.3 × 26.6 cm). A copy of this version sold at auction in October 2008 for USD $110,500.[16]

- A gelatin silver photograph printed by Stieglitz sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s (Key Set #314). The image measures approximately 47⁄16″ × 35⁄8″ (11.3 × 9.2 cm).

Several copies are known to exist of each version. Most are in major museums. Other prints with slightly different measurements are likely to be one of the five versions listed above. Image sizes may vary slightly from one copy to another due to paper shrinkage.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Stieglitz, Alfred (1942). "How The Steerage Happened". Twice a Year (8–9): 175–178.

- ↑ Whelan, Richard (2000). Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes. NY: Aperture. p. 197.

- ↑ "Great Ocean Liners: Kaiser Wilhelm II". Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Newhall, Beaumont (March 1988). "Alfred Stieglitz: Homeward Bound". Art News. 87 (3): 141–142.

- 1 2 3 4 Katherine Hoffman (2004). Stieglitz : A Beginning Light. New Haven: Yale University Press Studio. pp. 233–238.

- 1 2 3 Richard Whelan (1995). Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography. NY: Little, Brown. pp. 224–226.

- 1 2 Minneapolis Institute of Arts. "Alfred Stieglitz: The Steerage". Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Terry, James (July 1988). "The Problem of "The Steerage"". History of Photography. 6 (3): 211–215.

- ↑ Sarah Greenough (2000). Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and His New York Galleries. Washington: National Gallery of Art. p. 135.

- ↑ Orvel, Miles (2003). American Photography. Oxford University Press. p. 88.

- ↑ Hulick, Diana Emery (March 1992). "Photography: Modernism's Stepchild". Journal of Aesthetic Education. 26 (1): 75. doi:10.2307/3332729.

- ↑ Marius de Zayas (1944). History of an American: Alfred Stieglitz, 291 and After. Philadelphia Museum of Art. p. 7.

- ↑ John Hannavy, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Photography. 1. NY: Routledge. p. 1342.

- ↑ Richard Pitnick. "The Ermgence of Photography as Collectible Art". Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ↑ Sarah Greenough (2002). Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set. NY: Abrams. pp. 190–194.

- ↑ "Sotheby's: Auction Results: Photographs". Retrieved 2008-12-20.