The New Found World, or Antarctike

| |

| Author | André Thevet |

|---|---|

| Original title | Les singularitez de la France antarctique |

| Publisher | Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket |

Publication date | 1568 |

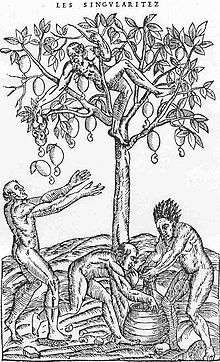

The New Found World, or Antarctike (French edition: Les singularitez de la France antarctique, autrement nommee Amerique, & de plusieurs terres et isles decouvertes de nostre temps, 1557) is an account published by the French Franciscan priest and explorer André Thevet detailing his experiences in France Antarctique, a French settlement in Rio de Janeiro.[1] Thevet based his descriptions of Rio de Janeiro on his ten weeks spent living in Brazil, as well as drawing on the reports of other travelers.[2] The first English translation of the book was published in 1568. Thevet describes the native people and the new experiences that he saw. He goes on to describe foods that they eat, clothing, the surrounding areas, and eventually their rituals. He goes into great detail discussing cannibalism and its common use among prisoners and enemies.[3][4]

Throughout the book there was a big emphasis on clothing in which Thevet makes very clear that often both men and women don't wear very much if any. They did wear jewelry as well as animal skins. Thevet also goes into detail about the food and drink that they were consuming. The native people would make an alcoholic wine like substance out of roots and would drink this until they felt sick. He compares this to Europeans drinking wine. While the natives do practice cannibalism it was done in a way that was much more humane than most people thought. They did kill war prisoners but leading up until his death they were often treated nicely and humanely.[4]

Synopsis

Thevet and his colleagues land on the Brazilian mainland on November 10, and are welcomed and fed by a delegation of native people immediately upon their arrival. At the welcoming feast, they are served an alcoholic beverage brewed from a combination of different roots. Initially hoping to venture inland or elsewhere along the coast, the expeditionary team members are informed that there is little freshwater for a significant distance away from the indigenous settlement but that they would be welcome to remain near their landing site for the time being. Venturing to a nearby inlet, Thevet and company are impressed by an array of colorful birdsㅡtheir feathers making an attractive decoration for the sparse garments of native peopleㅡand a generous bounty of fish, upon which local residents may subsist. Finally Thevet describes some of the local flora, including beautiful trees unseen in Europe and small vines utilized by the natives as accessories and for medicinal purposes.[5]

The Catholic author acknowledges and laments the absence of organized religion in the lives of indigenous people. Although they do believe in "Toupan"ㅡsome sort of higher being reigning above them and governing the climateㅡthey make no clear effort to worship or honor it as a collective.[6] Moreover, rather than believe in a great prophet similar to those venerated in Abrahamic faiths, the natives passively celebrate "Hetich," the figure allegedly responsible for teaching them to cultivate the roots that became an essential staple of their diet.[7] Thevet then digresses from this point, describing some alternative properties of the roots that emerge once separate varieties are subjected to certain external forces. Following this, the author momentarily touches upon how Christopher Columbus and his team were initially worshiped by local Amerindians, before losing this divine status once it was gradually discovered that they behaved and functioned as ordinary men. Cannibalism is addressed at the end of this chapter, being attributed to certain indigenous groups who allegedly consume human flesh as one in European society might consume any other meat.[8]

Thevet also describes, in some detail, the rarity of clothing in the aboriginal society he and his companions observe. Almost without exception, men and women alike would live their entire lives completely naked. Deviations from this norm might occur at formal events, at which attendees might wear sashes or headdresses. Additionally, elderly people might cover their breasts and genitalia out of an apparent desire to hide their physical deterioration wrought by the aging process. However, it is also notable that these indigenous villagers placed a great deal of value in the garments that they made or otherwise encountered. Rather than wear these articles of clothing, the natives would frequently set them aside for fear of degrading their quality. In those instances when they did choose to wear attire, the Amerindians would always do so on a part of their body where it could easily be prevented from touching the ground at any time. Noting their ability to weave cotton for other purposes, Thevet deduces that the natives likely embrace nudity as a way for them to move and fight with agility.[9]

Relatively late in the narrative, Thevet describes a method of execution which he claims is practiced by the coastal community in which he resides. Condemned men, typically war prisoners, are given comfortable lodging, plenty of food, and even a “wife” for the period of time leading from the beginning of their internment to their deaths.[10] The experience of captured women differed in that they were afforded greater mobility, but were also required to gather food and perform sexual favors for a predetermined man of the tribe. The unit of time throughout this period is the moon, rather than days, weeks, or months. On the final day before his or her execution, the prisoner is chained to a bed and is the subject of a ceremony in which community members gather and sing of their death. Finally, the condemned man or woman is brought to a public place, tied up, hacked to pieces, and consumed by the local populace. Male children are told to bathe in the blood of the victim, while women are tasked with eating the internal organs. All children born to a condemned man’s “widow” as a result of their copulation are to be "nurtured" for a brief period, before being cannibalized in the same manner as their father. The executioners, meanwhile, are honored and brilliantly accessorized with colorful feathers and body paint.[11]

Historical Context

The French sent its first group of ships to Brazil in 1555 to make colonization efforts as part of France Antarctique when Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon gained control of Guanabara Bay, now Rio de Janeiro.[12][13] Fort Coligny was then built there, this was used by the French to sell the Tupinambá as slaves.[12][13] The Tupinambá did not have any immunity to any of the diseases that the French exposed them to, which lead to the death of may of the Tupinambá.[13][12] In 1557 more ships arrive and eventually Villegagnon was forced to abandon Fort Coligny due to religious differences.[12][13] The individuals that forced Villegagnon out, included Jean de Léry and André Thevet. Léry attempted to return to France with very little food.[12][13] The Portuguese sent twelve ships in 1560 that gained control of Fort Coligny from the French.[13][12]

Reception

The New Found World, or Antartike was quickly spread throughout Europe after its publication.[14] Europeans at the time considered Thevet’s work as an, “unusual contribution to travel literature.”[14] In 1568, the book was translated into an English version, titled The New found vvorlde, or antarctike, wherein is contained woderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, Master Andrevve Thevet, and now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographer, and an Italian edition with the title Historia dell'India America detta altramente Francia Antartica, di M. Andre; tradotta di francese in lingva italian.[14][15] The positive reception the book received by the European population led to a rise in Thevet’s career.[15]

Selected Editions

The first English Edition was published in London in 1568.[1]

References

- 1 2 Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket.

- ↑ Conrad, Elsa. "André Thevet (1516?-1592)". The Renaissance in Print: Sixteenth-Century Books in the Douglas Gordon Collection.

- ↑ "The new found vvorlde, or Antarctike wherin is contained wo[n]derful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trées, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers". quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- 1 2 "The new found vvorlde, or Antarctike wherin is contained wo[n]derful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trées, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers". quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. pp. 31–40.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. p. 44.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. p. 60.

- ↑ Thevet, André (1568). The New found worlde, or Antarctike, wherein is contained wōderful and strange things, as well of humaine creatures, as beastes, fishes, foules, and serpents, trees, plants, mines of golde and siluer: garnished with many learned aucthorities, trauailed and written in the French tong, by that excellent learned man, master Andrevve Theuet. And now newly translated into Englishe, wherein is reformed the errours of the auncient cosmographers. London: Imprinted by Henry Bynneman, for Thomas Hacket. pp. 60–63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Conley, Tom. "Thevet Revisits Guanabarba". Hispanic American Historical Review. 80: 753 – via Ebsco host.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kenny, Neil. "Brazil". ABC CLO.

- 1 2 3 Cardozo, Manoel Da Silveira (July 1944). "Some Remarks Concerning André Thevet1". The Americas. 1 (1): 15–36. doi:10.2307/978333. ISSN 0003-1615.

- 1 2 Schlesinger, Roger (1985). "André Thevet on the Amerindians of New France". Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society. 10: 1–21. JSTOR 42952150.