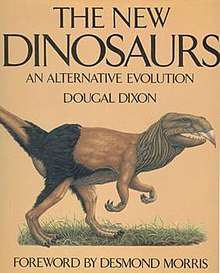

The New Dinosaurs

First Edition Cover | |

| Author | Dougal Dixon |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Speculative evolution |

| Publisher |

Salem House Publishers (US) Grafton (UK) |

Publication date |

1 September 1988 (US) 6 October 1988 (UK) |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 120 |

| ISBN | 978-0881623017 |

The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution is a 1988 speculative evolution book written by Scottish geologist Dougal Dixon and illustrated by several illustrators including Amanda Barlow, Peter Barrett, John Butler, Jeane Colville, Anthony Duke, Andy Farmer, Lee Gibbons, Steve Holden, Philip Hood, Martin Knowelden, Sean Milne, Denys Ovenden and Joyce Tuhill.[1] The book also features a foreword by Desmond Morris. The New Dinosaurs explores a hypothetical alternate Earth, complete with animals and ecosystems, where the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event never occurred, leaving non-avian dinosaurs and other Mesozoic animals an additional 65 million years to evolve and adapt over the course of the Cenozoic to the present day.

The New Dinosaurs is Dixon's second work on speculative evolution, following After Man (1981), which explored the animals of a hypothetical world 50 million years in the future where humanity had gone extinct. After Man used a fictional setting and hypothetical animals to explain the natural processes behind evolution whilst The New Dinosaurs uses its own fictional setting and hypothetical wildlife to explain the concept of zoogeography and biogeographic realms. It was followed by another speculative evolution work by Dixon in 1990, Man After Man, which focused on a hypothetical future path of evolution of humanity.[2]

Some of Dougal Dixon's hypothetical dinosaurs bear a coincidental resemblance to dinosaurs that were eventually discovered. As a general example, many of Dixon's fictional dinosaurs are depicted with feathers, something that was not yet widely accepted when the book was written.[2][3]

Summary

The New Dinosaurs explores Earth and its fauna in the present day (contrary to Dixon's other speculative evolution books After Man and Man After Man, both set in the future) as it would have been if the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event never occurred. Over the course of the Tertiary period and since the last Ice Age, several specialized descendants of various Mesozoic groups, in particular the dinosaurs, pterosaurs and plesiosaurs, have evolved. Dixon explores these new animals through biogeographic realms, divisions of the Earth's land surface based on distributional patterns of animals and other lifeforms.

The forests of the Ethiopian realm (Sub-Saharan Africa and Arabia) are home to several "abrosaurs", a group of small tree-climbing coelurosaurian theropods, including a wasp-eating variety. In the savanna, huge striding and terrestrial pterosaurs such as the giraffe-like "lank" are present whilst the deserts are home to coelurosaurs adapted to a lifestyle of effectively "swimming" through the sand and hunting small arthropods. On the island of Madagascar, some dinosaurs are highly similar to Mesozoic ones, such as titanosaurs and modern representatives of the genus Megalosaurus.

In the temperate climates of the Palearctic realm (Eurasia with the exception of Arabia, South-East Asia and India) there are small and colonial pachycephalosaurs and the "bricket", a fuzzy hadrosaur whose brightly colored tail can act as a warning signal. Predators include the "jinx", a dromaeosaurid adapted to mimic larger herbivorous dinosaurs through scent and appearance. In the deserts of the south, large ankylosaurs such as the "taranter" have adapted their ancestral armor to also function as a means to conserve moisture. In the far north, large migratory birds such as the "tromble" with legs almost like tree trunks, roam the land.

In the Nearctic realm (North America), most herbivores are members of the family Sprintosauridae, referred to as "sprintosaurs", descendants of the Mesozoic hadrosaurs adapted to a new lifestyle on the grass-covered plains. Also present on the plains are predatory dromaeosaurids and the "monocorn", a large and slow-moving ceratopsid. The mixed woodlands and wetlands are home to bipedal and fishing pterosaurs superficially similar to herons and the "springe", a large-brained descendant of Stenonychosaurus that has adapted an ambush-hunting strategy where it mimics being dead to attract scavengers that it can kill and eat.

The tropical rainforests of the Neotropical realm (South America and southern North America) are home to amphibious hypsilophodonts as well as highly specialized abrosaurs such as a pangolin-like form and a variety that feeds on nectar. Sauropods descended from the titanosaurs are present on the pampas grasslands, such as the heavily armored "turtosaur" and the trunked "lumber". The apex predator of the pampas, the "cutlasstooth", has evolved huge, cutting teeth to allow it to prey upon the large sauropods. The pampas is also home to the last of the tyrannosaurids, the large scavenging "gourmand".

The smallest biogeographic realm, the Oriental realm (South-East Asia and India) contains diverse environments and animals, such as the great "rajaphants" of the plains, massive sauropods living in herds, and bamboo-eating hypsilophodonts. In the swamps, there are aquatic hypsilophodonts that have evolved convergently with the amphibious hypsilophodonts of the Neotropical realm and pterosaurs using their wings as traps to lure in fish.

The Australasian realm (Oceania) is the most isolated and self-contained. In the scrub and tall grass savanna there are flamingo-like coelurosaurs and iguanodonts capable of jumping like kangaroos. There are also tree-living and herbivorous hypsilophodonts, superficially similar to the abrosaurs of the rest of the world, and terrestrial, fruit-eating pterosaurs that have completely lost their wings. The tropical islands surrounding Australia are home to the "coconut grab", an ammonite capable of spending more time on land than its ancestors and feeding on coconuts, which it sometimes climbs trees to get to.

The world's oceans are home to various pterosaurs, such as seagull-like and penguin-like forms. There is also the "whulk", a massive whale-like pliosaur that feeds exclusively on plankton. The "kraken", an enormous ammonite, uses specialized tentacles to entangle and sting anything that comes near it.

Development

Following the success of his previous speculative evolution book After Man in 1981, Dixon realized that there was a market for popular-level books which use fictional examples and settings to explain actual factual scientific processes. After Man had explained the process of evolution by creating a complex hypothetical future ecosystem, The New Dinosaurs was instead aimed at creating a book on zoogeography, a subject the general public was quite unfamiliar with, by using a fictional world in which the non-avian dinosaurs had not gone extinct to explain the process.[2]

The dinosaurs and other animals in The New Dinosaurs were heavily influenced by the paleontology of its time. The ideas of the Dinosaur Renaissance - replacing the older ideas of dinosaurs as dumb and slow creatures with active, agile and bird-like animals are heavily used in the book.[3] Dixon extrapolated on the ideas of paleontologists such as Robert Bakker and Greg Paul when creating his creatures and also used patterns seen in the actual evolutionary history of the dinosaurs and pushing them to an extreme, such as with the creation of the "gourmand", an armless and massive scavenger descended from the tyrannosaurids.[2]

Legacy

Many of the hypothetical animals created for The New Dinosaurs ended up resembling actual Mesozoic creatures that have since been discovered.[3] Many of the hypothetical dinosaurs featured in the book are covered in fuzzy integument, which in modern times have been discovered in dinosaurs of most groups. The tree-climbing abrosaurs are similar to actual tree-climbing small theropods such as Microraptor (described in 2000) and the large terrestrial pterosaurs, such as the "lank", resemble some animals in the actual pterosaur group Azhdarchidae.[2]

References

- ↑ Dixon, Dougal (1988). The New Dinosaurs. Salem House. ISBN 978-0881623017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Naish, Darren. "Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- 1 2 3 ""Alternative Evolution" of Dinosaurs Foresaw Contemporary Paleo Finds [Slide Show]". www.scientificamerican.com. Retrieved 2015-11-23.