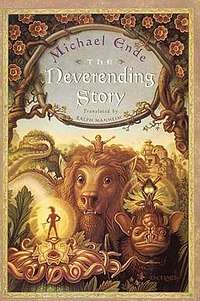

The Neverending Story

1997 Dutton edition cover | |

| Author | Michael Ende |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Unendliche Geschichte |

| Translator | Ralph Manheim |

| Illustrator | Roswitha Quadflieg |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Thienemann Verlag |

Publication date | September 1, 1979[1] |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 448 |

| ISBN | 3-522-12800-1 |

| OCLC | 7460007 |

| LC Class | PT2665.N27 U5 |

The Neverending Story (German: Die unendliche Geschichte) is a fantasy novel by German writer Michael Ende, first published in 1979. An English translation, by Ralph Manheim, was first published in 1983. The novel was later adapted into several films.

Plot summary

The book centers on a boy, Bastian Balthazar Bux, a small and strange child who is neglected by his father after the death of Bastian's mother. While escaping from some bullies, Bastian bursts into the antique book store of Carl Conrad Coreander, where he finds his interest held by a book called The Neverending Story. Unable to resist, he steals the book and hides in his school's attic, where he begins to read.

The story Bastian reads is set in the magical land of Fantastica, an unrealistic place of wonder ruled by the benevolent and mysterious Childlike Empress. A great delegation has come to the Empress to seek her help against a formless entity called "The Nothing". The delegates are shocked when the Empress's physician, a centaur named Cairon, informs them that the Empress is dying, and has summoned a boy warrior named Atreyu, to find a cure. To Atreyu, the Empress gives AURYN: a powerful medallion that protects him from all harm. At the advice of the giant turtle, Morla the Aged One, Atreyu sets off in search of an invisible oracle known as Uyulala, who may know the Empress's cure. In reaching her, he is aided by a luckdragon named Falkor, whom he rescues from the monster 'Ygramul the Many'. By Uyulala, he is told the only thing that can save the Empress is a new name given to her by a human child, who can only be found beyond Fantastica's borders.

As Falkor and Atreyu search for the borders of Fantastica, Atreyu is flung from Falkor's back in a confrontation with the four Wind Giants and loses AURYN in the sea. Atreyu lands in the ruins of Spook City, the home of various wicked creatures. Injured by the fall and stranded in the dangerous city, Atreyu finds the wolf G'mork, chained and near death, who tells him that all the residents of the city have leapt voluntarily into The Nothing. There, thanks to the irresistible pull of the destructive phenomenon, they have become lies in the human world. The wolf also reveals that he is a servant of The Manipulators, the force behind The Nothing. They wish to prevent the Empress's chosen hero from saving her. G'mork then reveals that when the princess of the city discovered his treachery against the Empress, she imprisoned him and left him to starve to death. When Atreyu announces that he is the hero G'mork has sought, the wolf laughs and succumbs to death. However, upon being approached, G'mork's body instinctively seizes Atreyu's leg in his jaws. Meanwhile, Falkor retrieves AURYN from the sea and arrives in time to save Atreyu from the rapid approach of The Nothing.

Falkor and Atreyu go to the Childlike Empress, who assures them they have brought her rescuer to her; Bastian suspects that the Empress means him, but cannot bring himself to believe it. When Bastian refuses to speak the new name, to prompt him into fulfilling his role as savior, the Empress herself locates the Old Man of Wandering Mountain, who possesses a book also entitled The Neverending Story, which the Empress demands he read aloud. As he begins, Bastian is amazed to find the book he is reading is repeating itself, beginning once again whenever the Empress reaches the Old Man—only this time, the story includes Bastian's meeting with Coreander, his theft of the book, and all his actions in the attic. Realizing that the story will repeat itself forever without his intervention, Bastian names the Empress 'Moon Child', and appears with her in Fantastica, where he restores its existence through his own imagination. The Empress has also given him AURYN, on the back of which he finds the inscription "DO WHAT YOU WISH".

For each wish, Bastian loses a memory of his life as a human. Unaware of this at first, Bastian goes through Fantastica, having adventures and telling stories, while losing his memories. In spite of the warnings of Atreyu and Bastian's other friends, Bastian uses AURYN to create creatures and dangers for himself to conquer, which causes some negative side effects for the rest of Fantastica. After encountering the wicked sorceress Xayide, and with the mysterious absence of the Childlike Empress, Bastian decides to take over Fantastica for himself, but is stopped by Atreyu, whom Bastian grievously wounds in battle. Ultimately, a repentant Bastian is reduced to two memories: those of his mother and father, and of his own name. After more adventures, Bastian must give up the memory of his parents to discover that his strongest wish is to be capable of love and give love to others.

After much searching, and on the verge of losing his final memory, Bastian is unable to find the Water of Life with which to leave Fantastica with his memories. Here, he is found by Atreyu. In remorse, Bastian lays down AURYN at his friend's feet, and Atreyu and Falkor enter AURYN with him, where the Water of Life demands to know Bastian's name, and if Bastian has finished all the stories he began in his journey, which he has not. Only after Atreyu gives Bastian's name and promises to complete all the stories for him does the Water of Life allow Bastian to return to the human world, along with some of the mystical waters. He returns to his father, where he tells the full tale of his adventures, and thus reconciles with him. Afterwards, Bastian confesses to Coreander about stealing his book and losing it, but Coreander denies ever owning such a book. Coreander reveals he has also been to Fantastica, and that the book has likely moved into the hands of someone else and that Bastian - like Coreander - will eventually show that individual the way to Fantastica. This, the book concludes, "is another story and shall be told another time".

Characters

- Atreyu

- Bastian Balthazar Bux

- The Childlike Empress/Moon Child

- Falkor, the luckdragon

- Carl Conrad Coreander

- Artax, Atreyu's horse

- Gmork, the wolf

- Morla, the giant turtle/the ancient one

- Uyulala, the invisible oracle

- Xayide, the witch

- Pyornkrachzark, the rock biter

- Engywook en Urgl

History of Origin and Publication

In 1977, Michael Ende's publisher, Hansjörg Weitbrecht, suggested Michael Ende write a new book. Ende promised to have it finished by Christmas but he doubted he would reach a page number beyond 100. Ende chose this leitmotif: "When reading a story, a boy falls - literally - into the story and finds it hard to get out again". Thienemann publishing approved this concept in advance.

It quickly became apparent, however, that there was much more material than Ende had thought. Because of this, the publication had to be postponed again and again. Ende promised that the book would be able to be published in autumn 1979. A year before this date, he called his publisher and told him that Bastian, the main character, had absolutely refused to leave Fantastica and that he (Michael Ende) had no choice but to accompany him on his long journey. He also said it could not be an ordinary book anymore. It had to be designed much more as a proper grimoire, or a book of magic, with a leather cover and decorated with mother-of-pearl and brass buttons. Eventually, they agreed on a silk cover, the familiar bi-color print and the twenty-six initials for the individual chapters, which were to be designed by Roswitha Quadflieg. The costs of the book increased significantly as a result.

Ende was not able to move forward with his story, however, because he was still looking for ways to get Bastian back to reality from Fantastica. In the middle of this artistic crisis, one of the coldest winters Ende had ever experienced set in. The water pipes froze, one pipe burst, the house was under water, and the walls started to mold. It was during this difficult period that the author came up with the perfect solution: AURYN, the Amulet of the Childlike Empress, itself would function as the exit out of Fantastica. In this way, Ende was finally able to finish his book in 1979, after three years of work.

The novel was released for the first time in September 1979 by the publisher Thienemann. The story brought the author international fame. He received the Buxtehuder Bull, the prize of the bookworms of the ZDF, the Wilhelm-Hauff-Price for the aid of literature for children and young people, the European prize for books for young people, the silver stylus of Rotterdam as well as the Grand Prix of the German Academy for literature for children and young people.

Today, Michael Ende’s estate can be found in the Deutsche Literaturarchiv Marbach. The original manuscript of The Neverending Story can be viewed in the Literaturmuseum der Moderne in Marbach, as part of its permanent collection.

Editions

In September 1979, Thienemann published the book, with a small initial print run of only 20,000 copies. Having garnered favorable critical reception from the start, the novel hit no. 5 on the Spiegel Bestseller List in July 1980 and stayed on the list for sixty weeks. In the following three years, there were 15 reprints of the novel, with nearly a million copies in circulation. By Michael Ende's death in 1995, the circulation figures had risen to 5.6 million. Thirty years after its publication, The Neverending Story has been translated into over 40 languages. Worldwide, its total circulation constitutes 10 million copies (alternative source: 40 million copies).

Usually, the book is not printed in black; most editions use two different colors. Red writing represents the story lines which take place in the human world, while blue-green writing stands for the events taking place in Fantastica, the Realm of Fantasy. This kind of variation facilitates the reader's understanding of the plot, since the ten-year-old protagonist Bastian Balthasar Bux shifts back and forth between the two worlds.

The Neverending Story consists of 26 chapters, each one beginning with a richly adorned initial from "A" to "Z" in alphabetical order. The book's design was developed in cooperation with the illustrator Roswitha Quadflieg. The book's 2004 reprint does away with both these initials as well as the green writing.

Ralph Manheim's English translation of the book has a different cover design, but it does include the two-color writing as well as the alphabetically arranged initials - the translations of the first words in each chapter were adapted accordingly.

In 1987, the first paperback version of the book was published by dtv-Verlag, followed by "Der Niemandsgarten" in 1998 as part of the "Edition Weitbrecht" with writings from Michael Ende's unpublished works. In this, you can find a novel fragment of the same name, which can be understood as a predecessor to The Neverending Story. As of 2004, a new edition with illustrations by Claudia Seeger has become available from Thienemann publishing. In addition to that, Piper Verlag published “Aber das ist eine andere Geschichte – Das große Michael Ende Lesebuch” (Eng. “But that is a different story – The big Michael Ende Reading Book”), containing the previously unpublished chapter “Bastian erlernt die Zauberkunst” (Eng. “Bastian learns how to do magic”). In 2009, Piper Verlag made The Neverending Story available as a paperback. Later on, Thienemann-Verlag added The Fantastica-Lexicon (a dictionary of terms used in Fantastica) to their line of books dealing with The Neverending Story.

Interpretation

As to the interpretation of The Neverending Story, Michael Ende has never wanted to set any limits. According to him, any interpretation could be right if it is well done. He does, however, have one thing to say about the story: “This is a story of a boy who loses his whole interior world, which basically is his mythical world, during the night of a crisis – a life crisis. It just disappears into nowhere and he has to face this nothing, this nowhere and that is what we Europeans, too, have to do. We have gotten rid of all the values we once had and now we have to face that, we have to bravely jump in order to be able to create something again, to create a new 'Fantastica' and a new set of values”.

Michael Ende has often been asked what the message of his novel is. Usually he would answer this question like he did in a letter to a reader: ‘’Art and Poetry don’t explain the world, they depict it. They do not need anything that exceeds them. They themselves are goals. A good poem does not exist to improve the world – it in itself is a piece of an improved world, which is why it does not need a message. This endless searching for a message (moral, religious, practical, social, etc.) is a deplorable invention of literary professors and essayists, who otherwise would not know what to write and babble about. The works of Shakespeare, the Odyssey, One Thousand and One Nights, and Don Quixote – the biggest works of literature don’t have a message. They don’t prove or disprove anything. They are something like a mountain, a lake, a deadly desert or an apple tree.

"People write because they are thinking about a topic, not because they have the intention or the urge to inform the reader about some important worldview. But that, of course, depends on how the theme one comes up with interacts with the world one has created. Well, I’ve never succeeded in bringing everything that is happening in my head into one collective structure. I neither make use of any philosophical system to answer every single of my questions, nor do I have an ideology which is fully developed – I am always on the go. There are some absolute terms which are of central importance for me; but the further away I move from them, towards the borders, things become very flexible and vague. My attempt has actually never really been to address any kind of audience, instead my lines are a conversation with god in which I don’t ask him for anything (as I assume that he knows anyway what we need and if we won’t get it then there must be a good reason for it) but rather I tell him how it is to be an imperfect human being among imperfect human beings. I suppose that god might be interested in that since this is an experience he has never been able to make".

“The Neverending Story” is usually considered a literary fairy tale. However, it only contains few characteristics of the fairy tale genre. Elements of the fairy tale are usually only imitated without containing a stable basis. By these means, Ende replaces the secret of the world, which once was part of myth and which also had an aesthetical expression in fairy tales, through the mystery of the self. While keeping the framework of a fairy tale, Ende changed the content of it.

Similar twists have also been used in science fiction and can be seen in the context of a postmodern identity crisis. Natural sciences have made the world more explainable and controllable, but they do not help in making more sense of the world. The resulting quest for meaning in science fiction has led to an exploration of the notion of “inner space”. In Ende’s novel, this quest leads to a mythologisation of the “Self”.

In view of this, the story’s fairy tale elements only play a supporting role. Stylistically, they are subordinate to other devices which are atypical for fairy tales. For the story’s plot and its purpose, however, the fairy tale elements are crucial and they are responsible for the novel’s massive success to a high degree.

The Neverending Story refrains from being analytical or educational, but conveys a clear message nevertheless. The novel opposes materialism and the devaluation of imagination. Michael Ende himself said: “I have searched my whole life for clues and ideas that could show us an alternative world view, in which not everything has to be proven to exist.” ("Ich habe Zeit meines Lebens nach Hinweisen und Gedanken gesucht, die uns herausführen könnten aus dem Weltbild des Nur-Beweisbaren"). Ende is making a case for equality between the world of hard facts and the world of imagination. The goal is to rediscover the fascination of existence, existence itself, in an intellectually impoverished world that is controlled by technology, and, since all human beings were once children themselves, to give adults the chance to fall under spell of imagination again, much as is the case in indigenous cultures.

Ende talks about the healing of humanity, about an ideal world, which he creates within the context of the classic division of good and evil. A place in which no child has to fear uncertainties of any kind. If one believes postmodern sociologist Jean Baudrillard, people nowadays live in a hermetical and nearly indestructible simulation of the world, in which neither up and down nor good and bad exist anymore. Instead, the world is riddled with exploitation, oppression and control of the individual. Although the situation seems hopeless, we need to do our best to improve it. What’s important is to never be on the losing side. This idea can be particularly burdensome for children. Children, much like indigenous peoples, require a certain kind of enchantment that grants them hope outside of the calculated confines of logic.

Ende elaborates on this idea during a conversation with Erhard Eppler and Hanne Tächl about the socio-cultural state of the world: On the outside, we have everything, but on the inside we are no more than poor wretches. We can’t see the future or find a utopia.

Modern-day humans lack a positive image of the world they live in: A utopia that can push back against the bleakness created by modern-day conceptions of the world. All this leads to a desperate desire for beauty and a hunger for wonder shared by adults and children alike.

The years after the war had been full of anxiousness, Ende maintained, everything was seen in a socio-critical, political, (…) rationalistic way and these postwar years pulled people further into a spiral of negativity, rage, bitterness and moroseness. Ende refuses to accept this exclusivity applied to literature and art. For him it was time to return to the world its sacred secret and give the people their dignity back: “Artists, poets and writers will play an important role when it comes to returning to life its magic and mystery”.

A writer’s responsibilities consist of renewing ancient values or creating new ones, says Ende. Michael Ende follows this principle as well and is searching for a utopia for society in order to renew its values. Like Thomas Morus’ Utopia, Ende also imagined a country that is not real: here, humanity will find its lost myths again. In doing so, he moves in a poetic landscape constructed based on the principles of the four cardinal directions: beauty, wonder, mystery and humor. Nevertheless, the mysteries of the world are revealed only to those who are willing to let themselves be transformed by them. To dive into this utopian world, Ende and his readers have to be open to free and aimless imagination. In his lecture in Japan, Ende illustrated how the free creative play of writing, due to its unplanned approach, becomes an adventure in itself. In regard to the development of The Neverending Story, he says that he literally fought for his life with this story.

If a human does not become a real adult - an unenchanted, mundane, sophisticated, crippled being, living in an unenchanted, mundane and sophisticated world of so-called facts - then the child continues to live within him and represents the future until the very last day of their life. Ende dedicates his works to the “eternal child” in everyone and that is why his writings ought not to be classified as children’s literature, he says. He chose a fairy tale format for artistic and poetic reasons. He says if one wanted to tell tales of certain wonderful occurrences, then they had to depict the world in such a way that such occurrences were possible and probable in it.

In a television interview with Heide Adams, he claimed that if he had become a painter, he would have drawn like Marc Chagall. In Chagall‘s art, he says, he sees his own way of looking at things. In their view of the world, they both stress the “core of the eternal child” which tells us that everything exists, and that this ‘everything’ is even more real than all the things on this side of reality. Working from this perspective, Michael Ende modifies Friedrich Nietzsche's statement that "In every man there is a hidden child that wants to play" to his own thesis: In every human being there is a hidden child that wants to play.

Ende considers art as the highest form of such play. For Michael Ende, poetry as well as the visual arts, primarily fulfill a therapeutic task because being born of the wholeness of the artist; both could return this wholeness to man. In a sick society, the poet takes on the task of a doctor who tries to cure, save and console people. But if he is a good doctor, Ende says, he will not try to teach or improve his patients. Ende has kept true to this principle. But his new myth is above all a renewal of the old. To establish that, Ende uses a variety of literary references. He uses well-known motifs and avails himself of numerous mythologies: the Greek‘s, the Roman’s and the Christian ones.

The book is predominately read by adults, who may, after reading it, resolve to give greater consideration to their creative, associative and emotional side of the brain. The novel mainly stresses the importance of dreaming. Its main point is to approach imagination with an open mind, as it supposedly shapes the perception of reality and thereby helps to bring something fantastic into everyday life. The ideas conveyed by The Neverending Story are the following: 1. Learning how to perceive the mundane as something magical which will eventually shape the worldview. 2. Learning how to love every human being as love is the most basic human desire. These conclusions might be trivial, but they are reoccurring motifs and serve an important purpose in the novel. Ende believes that imaginativeness and fictional thinking are neither a good nor a bad thing but that any kind of action will be judged based on a social perception of morality. Eventually, the outcome has a positive or negative effect. Ende adduces lying as an instance. According to him, a lie equals a perverted kind of fantasy which is used to manipulate and control others. Ende adds that repetitive lying ultimately undermines any authentic type of imagination though.

In his writings Ende puts a lot of emphasis on other issues such as the relationship between humanity and its maker: escape from reality, exercise of power, responsibility (especially responsible handling of the consequences of ones actions), selfconfidence and interpersonal relations. The silver lining of his works manifests itself in the idea that a journey into the world of phantasy can only ever lead to a positive end if it is also applied to ameliorate the real world. To this end he selected the protagonist Bastian Balthasar Bux's character traits with great care. In a letter to his publisher 1973, Ende complains about the craze for functionality in literature. In his opinion the portrayal of an entirely rational world aims to prohibit readers from exploring their own imagination. This is reflected in Bastian Balthasar Bux's incapability to cope with life: Most people's conception of the world as a purely rational and functional place does not make any sense to him. Ever since the death of his mother – an incident that neither him nor his father ever managed to process – they have been drifting apart. Because of that, Bastian finds refuge in books filled with phantasy, which create a world that appears more meaningful to him than his own.

The journey of the protagonist Bastian into the world of fantasy, into his own inner world, is therefore to be seen as an immersion into a forgotten reality, a “lost world of values”, as Michael Ende says himself, which needs to be rediscovered and renamed in order to become aware of it again. “Only the true name will give all creatures and things their reality”; says the Childlike Empress, looking for an eponym herself. Lastly, this is to be understood as an ode to love (‘’water of life’’), that, in order to grow, needs to be discovered over and over again. The human being goes on a journey of self-discovery to find his true self by letting his imagination run free; the protagonist is assigned to find and act upon his true will. The journey to Fantastica repressed for so long. In the end, Bastian succeeds in learning how to love by drinking from the waters of life; and by bringing those waters to his father, he releases him: Tears free him from the ice sheet, which held his inner life captive.

The novel is an ode to the inspiring and constructive power of the imagination and its beneficial impact on reality. At the same time it discusses the dangers that come with escaping into one’s own imagination.

Reception

Susan L. Nickerson of Library Journal writes in a review that "Imaginative readers know the story doesn't end when the covers close; the magic to be found in books is eternal, and Ende's message comes through vividly."[2]

"The two parts of the novel repeat each other", as Maria Nikolajeva states in her book The Rhetoric of Character in Children's Literature, in that Bastian becomes a hero but then in the second half he "acts not even as an antihero but as a false hero of the fairy tale." The characters of Bastian and Atreyu can also be seen as mirror halves.[3]

On September 1, 2016, the search engine Google featured a Google Doodle marking the 37th anniversary of The Neverending Story's first publishing.[1]

Adaptations and derivative works

Music

The album Wooden Heart by Listener was based on or heavily influenced by The Neverending Story, which has been confirmed by the band.[4] Different songs represent different ideas of the plot or characters, which can be seen on the band's lyric page for the album.[5]

The Spanish pop band Vetusta Morla derived its name from the ancient turtle in the novel.

Audiobook

A German dramatized audioplay under the title Die unendliche Geschichte (Karussell/Universal Music Group 1984, directed by Anke Beckert, music by Frank Duval, 3 parts on LP and MC, 2 parts on CD).

In March 2012 Tantor Media released an unabridged audiobook of The Neverending Story narrated by Gerard Doyle.

Film

The NeverEnding Story was the first film adaptation of the novel. It was released in 1984, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Barret Oliver as Bastian, Noah Hathaway as Atreyu, and Tami Stronach as the Childlike Empress. It covered only the first half of the book, ending at the point where Bastian enters Fantastica (renamed "Fantasia" in the film). Ende, who was reportedly "revolted" by the film,[1] requested they halt production or change the film's name, as he felt it had ultimately and drastically deviated from his novel; when they did neither, he sued them and subsequently lost the case.[6] The music was composed by Klaus Doldinger. Some electronic tracks by Giorgio Moroder were added to the US version of the film, as well as the titlesong Never Ending Story composed by Giorgio Moroder and Keith Forsey becoming a chart success for Limahl, the former singer of Kajagoogoo.[7]

The NeverEnding Story II: The Next Chapter, directed by George T. Miller and starring Jonathan Brandis and Kenny Morrison, was released in 1990. It used plot elements primarily from the second half of Ende's novel, but told a new tale.

The NeverEnding Story III, starring Jason James Richter, Melody Kay and Jack Black, was released in 1994 in Germany and in 1996 in the US. This film was primarily based only upon the characters from Ende's book, having an original new story. The film was lambasted by film critics and was a box office bomb.

Novels

From 2003 through 2004, the German publishing house AVAinternational published six novels of different authors in a series called Legends of Fantastica, each using parts of the original plot and characters to compose an entirely new storyline:

- Kinkel, Tanja (2003). Der König der Narren [The King of Fools].

- Schweikert, Ulrike (2003). Die Seele der Nacht [The Soul of the Night].

- Isau, Ralf (2003). Die geheime Bibliothek des Thaddäus Tillmann Trutz [The Secret Library of Thaddaeus Tillman Trutz].

- Fleischhauer, Wolfram (2004). Die Verschwörung der Engel [The Angels' Plot].

- Freund, Peter (2004). Die Stadt der vergessenen Träume [The City of Forgotten Dreams].

- Dempf, Peter (2004). Die Herrin der Wörter [Empress of the Words].

Stage

In Germany, The Neverending Story has been variously adapted to a stage play, ballet, and opera[8] which premiered at the Linz Landestheater on December 11, 2004. The scores to both the opera and the ballet versions were composed by Siegfried Matthus. The opera libretto was by Anton Perry.

Television

The 1995 animated series was produced by Nelvana, under the title of The Neverending Story: The Animated Adventures of Bastian Balthazar Bux. The animated series ran for two years, and had a total of twenty-six episodes. Director duties were split between Marc Boreal and Mike Fallows. Each episode focused on Bastian's further adventures in Fantastica, largely different from his further adventures in the book, but occasionally containing elements of them.

Tales from the Neverending Story, a one-season-only TV series that is loosely based on Michael Ende's novel The Neverending Story, was produced in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, through December 2000-August 2002 and distributed by Muse Entertainment, airing on HBO in 2002. It was aired as four two-hour television movies in the US and as a TV series of 13 one-hour episodes in the UK. The series was released on DVD in 2001.

Google Doodle

On 1 September 2016, a Google Doodle, created by Google artist Sophie Diao commemorated the publication of the work.[9]

Computer games

A text adventure game was released by Ocean Software in 1985 for the ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64 and Atari 800.[10]

A computer game based on the second film was released in 1990 by Merimpex Ltd under their Linel label and re-released by System 4 for the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64.[11]

In 2001, the German video game studio attraction published their Ende-inspired video game, AURYN Quest.[12]

Footnotes

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Neverending Story |

- 1 2 3 Graham, Chris (September 1, 2016). "What is the The Neverending Story, who wrote it and why is it worthy of a Google Doodle?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ Nickerson, Susan L. (1983-10-15). "Book Review: Fiction". Library Journal. R. R. Bowker Co. 108 (18): 1975. ISSN 0363-0277.

- ↑ Nikolajeva, Maria (2002). The Rhetoric of Character in Children's Literature. Scarecrow Press. pp. 106–108. ISBN 0-8108-4886-4.

- ↑ "Listener - Tickets - Downstairs - Chicago, IL - June 29th, 2016". Kickstand Productions. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- ↑ "Listner". iamlistener.com. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- ↑ Mori, Yoko. "Michael Ende Biography". Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ↑ Die unendliche Geschichte (1984) on IMDb

- ↑ "Die unendliche Geschichte" (in German). Online Musik Magazin.

- ↑ 37th Anniversary of The Neverending Story's First Publishing, google.com.

- ↑ "NeverEnding Story, The". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ "Neverending Story II, The". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

- ↑ "Auryn Quest for Windows". MobyGames. Retrieved 2007-06-23.