The Myth of the Eastern Front

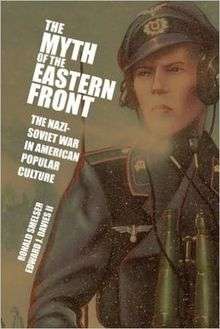

Book cover of The Myth of the Eastern Front; image adopted from cover art of the 1987 wargame The Last Victory: Von Manstein's Backhand Blow, February–March 1943, which depicts the Third Battle of Kharkov. | |

| Author | Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | History; Historiography |

| Publisher | Cambridge University Press |

Publication date | 2008 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | 978-0-521-83365-3 |

The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture is a 2008 book by the American historians Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies of the University of Utah. It discussed perceptions of the Eastern Front of World War II in the United States in the context of historical revisionism. The book traced the foundation of the post-war myth of the clean Wehrmacht, its support by U.S. military officials, and the impact of Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS mythology on American popular culture, up to the time of its publication.

The book garnered mixed reviews. The positive reviews commended its thorough analysis on the creation of the myth by German ex-participants and its entry into American culture. One reviewer described the book as a "tour de force of cultural historiography", and another observed that it "present[s] a discomforting portrait of the American views of the Eastern Front". It was also praised by several reviewers for its compelling analysis of contemporary war-romancing trends. Negative reviews noted its lack of perspective, failure to make its case, and a tendency to whitewash Red Army crimes on the Eastern Front. Other reviewers criticised the authors' analysis as lacking in important respects, particularly in its discussion on the myth's role in the contemporary culture, and its impact on popular perceptions of the Eastern Front, outside of a few select groups.

Background

At the time of the publication of The Myth of the Eastern Front, the authors were colleagues in the history department at the University of Utah. According to one reviewer, they were "well qualified for the task" of deconstructing the myth in the book's title: "Smelser is a widely published historian of Nazi Germany, while Davies, a self-confessed former adherent to the Ostfront myth, specializes in U.S. history".[1] In the preface to the book, Davies called the book's writing a "personal journey" and described how his interest in the Soviet-German war has grown out his reading Hitler Drives East by Paul Carell. Davies became a devotee, with hundreds of books on the Eastern Front in his library.[2] His private collection of wargames was part of the source material in the book.[3]

Structure

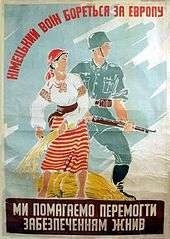

The first section of the book focused on the prevailing American attitudes towards Nazi Germany, the Wehrmacht, and the SS in the period during World War II and its immediate aftermath. Their sources were newspapers, magazines, and other American media of the period. The book also discussed the role of the war-time American propaganda in shaping a positive image of the Soviet Union as the United Kingdom's and the United States' ally.[4]

The book then covered positive views on the Germans, produced early in the Cold War era. These arose due to the changing geopolitical climate, the appearance of German military sources which vindicated their side of the conflict, and support of this effort by the American military. Such works "emphasized love of family, professions of Christianity, charity toward the enemy, and heroic self-sacrifice, [while ignoring] mass murder, anti-partisan warfare (deliberately mislabeled by the Nazi regime in 1942 as "combating bandits," or Bandenbekämpfung), property confiscation, complicity in forced labor roundups, and wanton destruction".[1] A review for H-Net found that "the authors do a thorough job discrediting the claims made by the German officers in their memoirs, which can no longer be viewed as even minimally respectable".[4]

The third section of the book covered the appearance of a new generation of "devotees of the German army and its campaigns in the east".[4] They included new authors, wargaming fans, and World War II reenactment participants. The review in H-Net found that this section provided "insightful and exciting research" and that "Smelser and Davies astutely identify a set of sources historians have rarely tapped and survey it thoroughly." They identified the so-called "gurus" of this generation, influential authors and speakers which presented "a heroic, sanitized picture of the German army in the east".[4]

Themes

In the words of one reviewer, the central myth described in the book boiled down to the following:[6]

The German army, or Wehrmacht, fought a "clean" and valiant war against the Soviet Union, devoid of ideology and atrocity. The German officer caste did not share Hitler's ideological precepts and blamed the SS and other Nazi paramilitary organizations for creating the war of racial enslavement and extermination that the conflict became.

The German Landser, or soldier, as far as conditions allowed, was generally paternal and kind to the Soviet citizens and uninterested in Soviet Jewry. That the German military lost this war was due in no way to its battlefield acumen, but to a combination of external factors, first and foremost Hitler's decisions. According to this myth, the defeat of Germany on the Eastern Front constituted a tragedy, not just for Germans, but for Western civilization.

The book deconstructed this myth and introduced several themes, which were, in the authors' opinion, important to the understanding of the origins, longevity, and the impact of Eastern Front mythology:

- The role of propaganda in shaping popular perceptions.[7]

- The role of the U.S. Army Historical Division in providing the German military commanders an opportunity to put down their recollections of Soviet-German conflict.[8]

- Parallels with the "Lost Cause" mythology in the post-American Civil War era.[4]

- The romanticisation of the German war effort in contemporary popular culture, especially with regards to the elite units such as the Waffen-SS.[8]

Reception

Lawrence Freedman in Foreign Affairs magazine called the book a "fascinating exercise in historiography", highlighting the book's analysis of how a "number of Hitler's leading generals were given an opportunity to write the history of the Eastern Front to help develop lessons for the Americans on fighting the Russians, and in doing so they provided a sanitized version of events". However, Freedman also noted that the impact of this involvement on U.S. perceptions of the Eastern Front was less clear.[9] The review by Joseph Robert White, titled "A Noble But Sisyphean Effort", concluded by quoting the book's closing sentence: "The 'good German' seems destined for an eternal life". White observed that the book should nonetheless provide food for thought in classroom discussions about the German army, but noted that an assumption of specialised knowledge and the concomitant lack of a chapter about war crimes committed by the Wehrmacht undermined the authors' efforts to challenge the myth.[1]

The military historian Jonathan House, who, together with David Glantz, wrote the 1995 book When Titans Clashed on the Soviet-German war, reviewed the book for The Journal of Military History, describing it as a "tour de force of cultural historiography". He noted Smelser's and Davies's analysis of the post-war mythology that presented the Wehrmacht and even the Waffen-SS as "above reproach, knights engaged in a crusade to defend Western civilization against the barbaric hordes of Bolshevism. (...) Ronald Smelser and Edward Davies have performed a signal service by tracing the origin and spread of this mythology". House recommended that military historians not only study the book, but "use it to teach students the dangers of bias and propaganda in history". He also noted that in exploring its subject, the book provided a "one-sided view of the historiography" by not taking into account the contemporary, balanced works on the Soviet-German war, such as by Glantz and others.[7]

Benjamin Alpers, in The American Historical Review, the official publication of the American Historical Association, noted that the book "present[s] a discomforting portrait of the American views of the Eastern Front. The authors are to be commended for exploring sources such as website and war games, that, while usually not studied by historians, are places where Americans encounter and enact World War II memory". However, the review also concluded that the authors' analysis of their material "is not entirely convincing", and also observed that they underplayed key divergences in their analogy between neo-Confederate ideas of the American Civil War and the mythic views of the Eastern Front.[10]

Professor Christopher A. Hartwell provided a critical assessment of the book in a review published in German Studies Review. He described the book as "interesting, but ultimately disappointing" and argued that the authors committed several egregious errors, with the most prominent being the whitewash of Red Army crimes on the Eastern Front, while denigrating those [authors] who do mention them "as contributing to the exoneration of the Wehrmacht". He noted that the book tends to suffer from a lack of perspective "on the effect the German generals had on the broader American perception of the war [on the Eastern Front]." Furthermore, Hartwell stated that the effect and influence of those "romancers" on American culture was not "impressively support[ed]" in the thesis, and the case that "romancers" were able to "effectively spread the myth of the innocent Wehrmacht" was not made out. Due to the lack of perspective, the book tended to lump together "those with an interest in military history and those who actually subscribe to neo-Nazi beliefs", and Hartwell concluded: "As it stands now, however, this tome has the feel of a dissertation that is trying too hard to find a niche that hasn't seen the light of day".[11]

Kelly McFall of Newman University described the book as a "fascinating immersion into a simple but important question: How did the German soldiers who fought on the eastern front during World War Two become hero figures to so many Americans?" McFall found the discussion on the iconography of the 1970s and 1980s wargames to be "path-breaking" and noted that the authors convinced her of the "existence of a community of 'buffs' who have made a fetish of the German army as super-efficient and super-heroic". However, she added that it was unclear how influential this community is outside of its niche, and what impact the rise of computer gaming may have had on this group.[4]

David Wildermuth of Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania concurred with the author's argument regarding the potential danger of "depoliticizing a conflict which at its core was a war of racial subjugation and conquest". He found the authors' analysis of war-romancing trends to be "deep and compelling", but noted the book's limitations in assuming specialist knowledge, which made it less accessible to the general public. For example, lay readers would have benefited from the context of the differences between Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht, along with an overview of the war crimes committed by the Waffen-SS, "especially in light of the falsehoods appearing daily in Internet website chatrooms". The reviewer also remarked on the occasional sniping which made palpable the authors' frustrations with romantic notions of a "valiant German military". Despite this minor criticism, Wildermuth commended the book for its "fascinating analysis on how, far removed from its time and place, the echoes of this war still reverberate".[6]

Martin H. Folly provided a critical assessment of the book in a review published in the journal History. While he complimented the authors for setting out the main myths concerning the Eastern Front, he argued that they did not provide convincing evidence to support their argument that most Americans accept such an account of the German-Soviet war. Moreover, Folly stated that the book overlooked the influence of prominent and more accurate accounts of the war on the Eastern Front. His summary was that "the book therefore delivers a rather weak conclusion, which dilutes the impact of the useful analysis earlier in the book on the creation of the myth by German ex-participants and its entry into American culture with the help of the US Army".[12]

American historian Dennis Showalter, in his review of the book for the journal Central European History, described the book as "incomplete", noting that "Eastern Front romanticism has cultural as well as intellectual matrices that are a good deal more complex than Smelser and Davis acknowledge", such as the appeal of "individual struggle against overwhelming odds" in the German narratives of the war, vs the Soviet emphasis on the collective. He also described how the Soviet World War II historiography, overly dogmatic and propaganda-driven, remained untranslated in the West, allowing the German view of the conflict to dominate academic and popular perceptions.[8]

Showalter acknowledged that the romanticised views described in the book existed, but argued that they remain limited in their impact on the wider popular culture: "Third Reich military memorabilia thrives—but in a niche market. (...) Eastern Front enthusiasts—who buy a disproportionate number of the books romanticizing the Eastern Front—are a minority within a minority, and, as a rule, are at some pains to deny sympathy with the Third Reich". The reviewer concludes that opening of the Russian archives since the fall of the Soviet Union has enabled "balanced analysis at academic levels", leading to a new interest in the Red Army operations from the popular history writers and the World War II enthusiasts.[8]

Cover art

The book's cover art, which spanned the front and the back, featured an image adopted from the 1987 wargame The Last Victory: Von Manstein's Backhand Blow, February–March 1943 from Clash of Arms Games. The game was devoted to the Third Battle of Kharkov, which, under the command of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, resulted in the recapture of the city and the stabilisation of the front following the Wehrmacht's defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad.[13]

The box cover art depicted a German panzer commander with a "stern-looking face". The authors described the image: "He is standing up, in an open hatch. Behind him is a line of Tiger tanks stretching along a city street. In the background, in blue with mist and smoke rising, stands Kharkov. The Nazi swastika sits in a lit circle to the top left of the cover". The book further noted that the accompanying materials "praise Manstein for his brilliance and his ability to recognise the assets of extremely able commanders under him", such as Paul Hausser, who led a Waffen-SS panzer corps during the battle.[13]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 White 2008.

- ↑ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. xi–xii.

- ↑ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 316.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McFall 2010.

- ↑ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 191.

- 1 2 Wildermuth 2016.

- 1 2 House 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Showalter 2009.

- ↑ Freedman 2008.

- ↑ Alpers 2008, p. 1578.

- ↑ Hartwell 2009.

- ↑ Folly 2010.

- 1 2 Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 191–193.

Bibliography

- Alpers, Benjamin L. (2008). "Ronald Smelser, Edward J. Davies. The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture". The American Historical Review. 113 (5): 1578.

- Carrard, Philippe (2010). The French Who Fought for Hitler: Memories from the Outcasts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521198226.

- Folly, Martin H. (October 2010). "The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. By Ronald Smelser and Edward L. Davies II". History. 320 (4): 846.

- Freedman, Lawrence D. (2008). "Review: The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 2015-03-21. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Hartwell, Christopher A. (2009). "Review: The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture". German Studies Review. Johns Hopkins University Press. 32 (2): 431–432. JSTOR 40574826.

- House, Jonathan (December 2008). "Review: The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture" (PDF). The Journal of Military History, 73(2):681-682. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- McFall, Kelly (2010). "Tracing the Resurrection of a Reputation: How Americans Came to Love the German Army". H-Net. Archived from the original on 2015-03-21. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Showalter, Dennis (June 2009). "Book Review: The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. By Ronald Smelser and Edward L. Davies II". Central European History. Cambridge University Press. 42 (2): 375–377. doi:10.1017/S0008938909000491.

- Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83365-3.

- White, Joseph Robert (2008). "A Noble But Sisyphean Effort". H-Net. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Wildermuth, David (2016). "Mythbusters: Uncovering the Real Authors behind the Myth of the Eastern Front". H-Net. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

External links

- Official book page at Cambridge University Press

- "On Being a Wiking": the historian Robert Citino on Waffen-SS reenactment and being a wargamer, HistoryNet