The Handmaid's Tale (film)

| The Handmaid's Tale | |

|---|---|

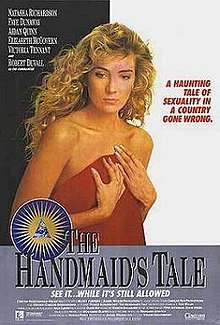

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Volker Schlöndorff |

| Produced by | Daniel Wilson |

| Screenplay by | Harold Pinter |

| Based on |

The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ryuichi Sakamoto |

| Cinematography | Igor Luther |

| Edited by | David Ray |

| Distributed by | Cinecom Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13,000,000 |

| Box office | $4,960,385[1] |

The Handmaid's Tale is a 1990 film adaptation of Margaret Atwood's novel of the same name. Directed by Volker Schlöndorff, the film stars Natasha Richardson (Kate/Offred), Faye Dunaway (Serena Joy), Robert Duvall (The Commander, Fred), Aidan Quinn (Nick), and Elizabeth McGovern (Moira).[2] The screenplay was written by Harold Pinter.[2] The original music score was composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto. MGM Home Entertainment released an Avant-Garde Cinema DVD of the film in 2001. The film was entered into the 40th Berlin International Film Festival.[3]

Plot

In the near future, war rages across the Republic of Gilead—formerly the United States of America—and pollution has rendered 99% of the population sterile. Kate is a woman who attempts to emigrate to Canada with her husband and daughter. As they take a dirt road, the Gilead Border Guard orders them to turn back or they will open fire. Kate's husband uses an automatic rifle to draw the fire, telling Kate to run, but he gets shot. Kate gets captured, while their daughter wanders off into the back country, confused and unaccompanied. The authorities take Kate to a training facility with several other women, where she and her companions receive training to become Handmaids—concubines for one of the privileged but barren couples who run the country's religious fundamentalist regime. Although she resists being indoctrinated into the cult of the Handmaids, which mixes Old Testament orthodoxy with scripted group chanting and ritualized violence, Kate is soon assigned to the home of "the Commander" (Fred) and of his cold, inflexible wife, Serena Joy. There she is named "Offred"—"of Fred".

Her role as the Commander's latest concubine is emotionless. She lies between Serena Joy's legs while being raped by the Commander in the collective hope that she will bear them a child. Kate continually longs for her earlier life, but she is haunted by nightmares of her husband's death and of her daughter's disappearance. A doctor tells her that many of Gilead's male leaders are as sterile as their wives. Serena Joy desperately wants a baby, so she persuades Kate to risk the punishment for fornication—death by hanging—in order to be fertilized by another man who may make her pregnant, and consequently, spare her life. In exchange for Kate agreeing to this, Serena Joy provides information to Kate that her daughter is alive, and shows as proof a recent photograph of her living in the household of another Commander. However, Kate is told she can never see her daughter. The Commander also tries to get closer to Kate, in the sense that he feels if she enjoyed herself more she would become a better handmaid. The Commander knows Kate's background as a librarian. He gets her hard-to-obtain items and allows her access to his private library. However, during a night out, the Commander has sex with Kate in an unauthorized manner. The other man selected by Serena Joy turns out to be Nick, the Commander's sympathetic chauffeur. Kate grows attached to Nick and eventually becomes pregnant with his child.

Kate ultimately kills the Commander, and a police unit then arrives to take her away. She thinks that the policemen are members of the Eyes, the government's secret police. However, it turns out that they are soldiers from the resistance movement (Mayday), of which Nick, too, is a part. Kate then flees with them, parting from Nick in an emotional scene.

Kate is now free once again and wearing non-uniform clothes, but facing an uncertain future. She is living by herself, pregnant in a trailer while receiving intelligence reports from the rebels. She wonders if she will be reunited with Nick, but expresses hope that will happen, and resolves with the rebels' help she will find her daughter.

Cast

- Natasha Richardson as Kate/Offred

- Robert Duvall as Commander

- Faye Dunaway as Serena Joy

- Elizabeth McGovern as Moira

- Aidan Quinn as Nick

- Victoria Tennant as Aunt Lydia

- Blanche Baker as Ofglen

- Traci Lind as Janine/Ofwarren

- Reiner Schöne as Luke, Kate's husband

- Robert D. Raiford as Dick

- Muse Watson as Guardian

- Bill Owen as TV Announcer #2

- David Dukes as Doctor

- Blair Nicole Struble as Jill, Kate's daughter

Development

Writing

According to Steven H. Gale, in his book Sharp Cut, "the final cut of The Handmaid's Tale is less a result of Pinter's script than any of his other films. He contributed only part of the screenplay: reportedly he 'abandoned writing the screenplay from exhaustion.' … Although he tried to have his name removed from the credits because he was so displeased with the movie (in 1994 he told me that this was due to the great divergences from his script that occur in the movie), … his name remains as screenwriter".[4]

Gale observes further that "while the film was being shot, director Volker Schlöndorff", who had replaced the original director Karel Reisz, "called Pinter and asked for some changes in the script"; however, "Pinter recall[ed] being very tired at the time, and he suggested that Schlondorff contact Atwood about the rewrites. He essentially gave the director and author carte blanche to accept whatever changes that she wanted to institute, for, as he reasoned, 'I didn't think an author would want to fuck up her own work.' … As it turned out, not only did Atwood make changes, but so did many others who were involved in the shoot".[4] Gale points out that Pinter told his biographer Michael Billington that

It became … a hotchpotch. The whole thing fell between several shoots. I worked with Karel Reisz on it for about a year. There are big public scenes in the story and Karel wanted to do them with thousands of people. The film company wouldn't sanction that so he withdrew. At which point Volker Schlondorff came into it as director. He wanted to work with me on the script, but I said I was absolutely exhausted. I more or less said, 'Do what you like. There's the script. Why not go back to the original author if you want to fiddle about?' He did go to the original author. And then the actors came into it. I left my name on the film because there was enough there to warrant it—just about. But it's not mine'.[5][4]

In an essay on Pinter's screenplay for The French Lieutenant's Woman, in The Films of Harold Pinter, Gale discusses Pinter's "dissatisfaction with" the "kind of alteration" that occurs "once the script is tinkered with by others" and "it becomes collaborative to the point that it is not his product any more or that such tinkering for practical purposes removes some of the artistic element";[6] he adds: "Most notably The Handmaid's Tale, which he considered so much altered that he has refused to allow the script to be published, and The Remains of the Day, which he refused to allow his name to be attached to for the same reason …" (84n3).[7]

Pinter's screenplay

Christopher C. Hudgins discusses further details about why "Pinter elected not to publish three of his completed filmscripts, The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day, and Lolita," all of which Hudgins considers "masterful filmscripts" of "demonstrable superiority to the shooting scripts that were eventually used to make the films"; fortunately ("We can thank our various lucky stars"), he says, "these Pinter filmscripts are now available not only in private collections but also in the Pinter Archive at the British Library"; in this essay, which he first presented as a paper at the 10th Europe Theatre Prize symposium, Pinter: Passion, Poetry, Politics, held in Turin, Italy, in March 2006, Hudgins "examin[es] all three unpublished filmscripts in conjunction with one another" and "provides several interesting insights about Pinter's adaptation process".[8]

Richardson's views

In a retrospective account written after Natasha Richardson's death, for CanWest News Service, Jamie Portman cites Richardson's view of the difficulties involved with making Atwood's novel into a film script:

Richardson recognized early on the difficulties in making a film out of a book which was "so much a one-woman interior monologue" and with the challenge of playing a woman unable to convey her feelings to the world about her, but who must make them evident to the audience watching the movie. … She thought the passages of voice-over narration in the original screenplay would solve the problem, but then Pinter changed his mind and Richardson felt she had been cast adrift. … "Harold Pinter has something specific against voice-overs," she said angrily 19 years ago. "Speaking as a member of an audience, I've seen voice-over and narration work very well in films a number of times, and I think it would have been helpful had it been there for The Handmaid's Tale. After all it's HER story."

Portman concludes that "In the end director Volker Schlondorff sided with Richardson"; Portman does not acknowledge Pinter's already-quoted account that he gave both Schlondorff and Atwood carte blanche to make whatever changes they wanted to his script because he was too "exhausted" from the experience to work further on it; in 1990, when she reportedly made her comments quoted by Portman, Richardson herself may not have known that.[9]

Filming locations

The scene where the hanging occurred was filmed in front of Duke Chapel on the campus of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.[10] Several scenes were filmed at Saint Mary's School in Raleigh, N.C.

Reception

Rotten Tomatoes reports that five of the sixteen counted critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating was 4.8/10.[11] Roger Ebert gave the film two out of four stars and wrote that he was "not sure exactly what the movie is saying" and that by "the end of the movie we are conscious of large themes and deep thoughts, and of good intentions drifting out of focus."[12] Owen Gleiberman, writing for Entertainment Weekly, gave the film a "C-" grade and commented that "visually, it's quite striking", but that it is "paranoid poppycock — just like the book".[13]

References

- ↑ "The Handmaid's Tale". Box Office Mojo.

- 1 2 Maslin, Janet (March 7, 1990). "Review/Film; 'Handmaid's Tale,' Adapted From Atwood Novel". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 1990 Programme". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- 1 2 3 Gale, Steven H. (2003). Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter's Screenplays and the Artistic Process. Lexington, KY: The UP of Kentucky. pp. 318–319. ISBN 978-0-8131-2244-1.

- ↑ Pinter, as quoted in Harold Pinter, 304

- ↑ Gale, 73

- ↑ Cf. "Harold Pinter's Lolita: 'My Sin, My Soul'", by Christopher C. Hudgins: "During our 1994 interview, Pinter told [Steven H.] Gale and me that he had learned his lesson after the revisions imposed on his script for The Handmaid's Tale, which he has decided not to publish. When his script for Remains of the Day was radically revised by the James Ivory–Ismail Merchant partnership, he refused to allow his name to be listed in the credits" (Gale, Films 125).

- ↑ Hudgins, 132

- ↑ Referring to Pinter's screenplay for the film of John Fowles's novel The French Lieutenant's Woman, Gale observes: "Although in other films he has used a voice-over narrator, the obvious choice for retaining the Fowles touch, Pinter is on record as not being fond of the device, and he wanted to avoid it here if possible" (Sharp Cut 239); in relation to his screenplay for Lolita, "Despite the director's wanting him to use a good bit of that narrative as voice-over in the film, Pinter insist[ed] that he would never use it in a description of action … [and, Gale describes] how he put his opinion into practice" (358). Gale discusses the use of voice-over in or relating to other screenplays by Pinter, including those that he wrote for Accident, The Comfort of Strangers (in which Richardson also stars), The Go-Between, The Last Tycoon, The Remains of the Day, and The Trial (198–99, 234, 327, 353-54, 341, 367), as well as the voice overs that he did write for his script of The Handmaid's Tale:

The novel does not include the murder of the Commander, and Kate's fate is left completely unresolved—the van waits in the driveway, "and so I step up, into the darkness within; or else the light" ([Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986)] 295). The escape to Canada and the reappearance of the child and Nick are Pinter's inventions for the movie version. As shot, there is a voice-over in which Kate explains (accompanied by light symphonic music that contrasts with that of the opening scene) that she is now safe in the mountains held by the rebels. Bolstered by occasional messages from Nick, she awaits the birth of her baby while she dreams about Jill, whom she feels she is going to find eventually. (Gale, Sharp Cut 318)

- ↑ "April 18: Minutes of the Academic Council, Academic Council Archive, Duke University, 18 Apr. 1996, Web, 9 May 2009.

- ↑ "The Handmaid's Tale (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1990-03-16). "The Handmaid's Tale". Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (1990-03-09). "The Handmaid's Tale". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

Works cited

- Billington, Michael. Harold Pinter. London: Faber and Faber, 2007. ISBN 978-0-571-23476-9 (13). Updated 2nd ed. of The Life and Work of Harold Pinter. 1996. London: Faber and Faber, 1997. ISBN 0-571-17103-6 (10). Print.

- Gale, Steven H. Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter's Screenplays and the Artistic Process. Lexington, KY: The UP of Kentucky, 2003. ISBN 0-8131-2244-9 (10). ISBN 978-0-8131-2244-1 (13). Print.

- –––, ed. The Films of Harold Pinter. Albany: SUNY P, 2001. ISBN 0-7914-4932-7. ISBN 978-0-7914-4932-5. Print. [A collection of essays; does not include an essay on The Handmaid's Tale; mentions it on 1, 2, 84n3, 125.]

- Hudgins, Christopher C. "Three Unpublished Harold Pinter Filmscripts: The Handmaid's Tale, The Remains of the Day, Lolita." The Pinter Review: Nobel Prize / Europe Theatre Prize Volume: 2005–2008. Ed. Francis Gillen with Steven H. Gale. Tampa: U of Tampa P, 2008. 132–39. ISBN 978-1-879852-19-8 (hardcover). ISBN 978-1-879852-20-4 (softcover). ISSN 0895-9706. Print.

- Johnson, Brian D. "Uphill Battle: Handmaid's Hard Times." Maclean's 26 Feb. 1990. Print.

- Portman, Jamie (CanWest News Service). "Not the Tale of a Handmaid: Natasha Richardson Has Led an Outspoken Career". Canada.com. CanWest News Service, 18 Mar. 2009. Web. 24 Mar. 2009.

External links

- The Handmaid's Tale on IMDb

- The Handmaid's Tale at AllMovie

- The Handmaid's Tale at Rotten Tomatoes

- Gilbert, Sophie (24 March 2015). "The Forgotten Handmaid's Tale". The Atlantic. Retrieved 24 March 2015.